How many great writers of the last 150 years have turned out to be gay! In England they range from Oscar Wilde to Virginia Woolf to Christopher Isherwood to Alan Hollinghurst (though Wilde’s grandson once told me that Oscar should be considered “bisexual”); in France, from André Gide to Marcel Proust to Jean Genet to François Mauriac; in America, James Baldwin and Willa Cather and Hart Crane and Henry James and Walt Whitman and Gertrude Stein; in Germany, Thomas Mann and Stefan George; in Russia, Mikhail Kuzmin; and in Belgium, Georges Eekhoud.

It used to be a familiar practice among the self-hating homosexuals of my youth in the 1950s to list the greats in history who were gay, which both promoted them and discredited them in our eyes, so low was our self-esteem (“Leonard Bernstein? Oh, her, I’ve had huh”). But the more we read the letters and diaries of the artistic geniuses of the past, the more we discover that they were often either practicing or repressed homosexuals, which isn’t so odd, since homosexuality, given a chance, is a natural choice of a large part of our species. But it was such shameful, even criminal behavior for so long that it could become an obsession, and obsessions focus powers of observation, as Proust argued.

In The Master Colm Tóibín brilliantly dramatized the inner life of a closet queen, Henry James, who arguably never passed to the act. Tóibín has his ringmaster of “supersubtle fry” never even think about his dreadful temptations; it’s fascinating to watch him veer away from any overly clear sexual impulse. E.M. Forster seems to have been much more conscious of his suppressed (rather than repressed) desires, though he was thirty-seven before he got laid. In Howards End a character famously declares, “Only connect,” and Forster seems to have tried to live by that creed. In several novels he also declared that love truly is eternal, a surprisingly optimistic idea from such a disabused man.

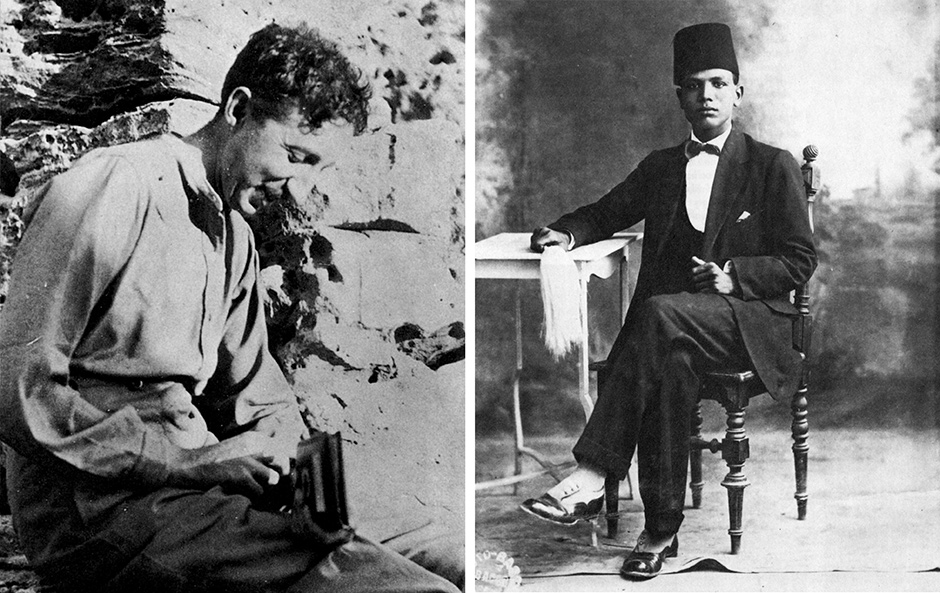

Forster came to the expression of his urges late and after much fretting, which is the subject of Damon Galgut’s beautifully written Arctic Summer (the name of a novel Forster started but never finished). In 1906 he had fallen in love with a handsome, tall Indian grand bourgeois, Syed Ross Masood, a seventeen-year-old future Oxford undergraduate whom he tutored in Latin. Masood had a romantic, poetic view of friendship and confused his tutor by making constant avowals of his love. Alas, the two men had very different notions about what these words meant. Finally Morgan, as we shall call Forster’s character in Galgut’s novel based on the writer’s life, wrote in his diary, “He is not that sort—no one whom I like seems to be.”

I remember once having an old Indian, a regional minister of education, to dinner. I asked him if he had ever known Nehru and he replied, “I met a man and I fell in love.” Our eyebrows all shot up, but his son later explained to me that in the flowery language of his generation that just meant they were fast friends.

When Forster’s feelings for Masood weren’t reciprocated, even though he made a trip to India to cement the relationship, the Englishman found himself, during World War I, falling in love with a tramway conductor in Alexandria, where he’d been given war work as a “searcher” (someone who located missing wounded British soldiers). The young man (also heterosexual), named Mohammed el-Adl, was more obliging sexually than Masood, possibly because he was poorer. Outside the scope of Galgut’s novel lies Forster’s final, more satisfying love with a married English policeman named Bob Buckingham.

Whereas a biography might treat Forster’s homosexuality as something peripheral, in Galgut’s novel it is definitive. Morgan goes to India in search of a man, and ultimately his greatest novel, A Passage to India (a name derived from another homosexual’s Leaves of Grass), is the fruit of his two longish stays on the subcontinent. Although there is nothing homosexual in the book, he took years away from completing it in order to write Maurice, his unpublished (and unpublishable) homosexual romance (it was eventually published in 1971, a year after his death). He also wrote a few posthumously published short stories that had some mild homosexual content.

Galgut shows how Morgan’s desires played into his travels and his literary production—and shows it in a way that no biography could do without lots of those reprehensible sentences such as “He must have felt…” or “Inevitably he would have thought….” Throughout Arctic Summer there is a lot of intelligent analysis, a tracing of the stages Morgan (the character) goes through. The novel begins with his first journey to India in 1912. Another passenger is a British army man named Seawright who is heading for Lahore where, he confides, “the Pathans are a breed of young savages, and I intend to make friends with many of them.” The prissy Morgan is alarmed by the man’s assumptions. Seawright gloats with Morgan over nude photos of Sicilian adolescents by the German Baron Wilhelm von Gloeden. Seawright says, “And look at his sultry cock, angled to the left at about forty-five degrees. It’s a real beauty.”

Advertisement

Morgan has never before participated in such a frank and literally shameless conversation. For him “the world of Eros remained a flickering internal pageant.” The whole encounter translates itself into “the beginnings of a story.” We learn that for Morgan “there were times when lust felt like a kind of idealism”—that is, all his nobler sympathies were ignited by passion. For instance, he is infuriated by British racism in India and the condescending presumptions of empire—but his physical attraction to the “natives” raises troubling questions for his politics.

In India Morgan has to face the fact that his lust for Masood is not reciprocated. After two and a half weeks together, he tries to kiss his friend. “In the fizzing white burn of the lamp-light, his friend’s face had been at first astonished, and then shocked,” Galgut writes.

His hand had come up sharply, to push Morgan away, and that little movement had felt enormous, a force that could move a boulder. Morgan had accepted the refusal, because he’d known in advance it would come, and sat miserably over his kernel of loneliness.

Simultaneously Morgan is becoming more and more aware of the political tensions in India—between Muslims and Hindus and between Indians and the British. He perceives these conflicts in Masood, whose “political musings” back in England “had always had a theatrical quality, as if he were performing his beliefs rather than feeling them.”

While in India, Morgan becomes aware that for a Brit to befriend a wog is considered eccentric—which becomes one of the major themes in A Passage to India. Forster’s young Englishwoman, Adela, newly arrived in India and engaged to marry a British officer, wants to become intimate with Indians—as Forster himself did—and she is worried that she will become rude to them in a year, as she has heard every colonial does. All the seasoned Brits tell her that it’s impossible to befriend an Indian and that she will soon get over her naive enthusiasms. The English are portrayed as narrow-minded bigots, with few exceptions.

Masood gets married. He treats Morgan shabbily. Finally in a letter Morgan explodes: “You can now go to hell as far as I’m concerned.”

Forster himself, by our lights, could be quite incorrect politically. In Howards End Leonard Bast’s wife makes grammatical mistakes that prove she is hopelessly stupid. In A Passage to India he generalizes constantly about the “Oriental,” which can make us squirm: “Like most Orientals, Aziz overrated hospitality, mistaking it for intimacy, and not seeing it is tainted with the sense of possession.” Of a physically superb servant plying a fan in a courtroom, Forster writes:

Almost naked, and splendidly formed, he sat on a raised platform near the back…and he seemed to control the proceedings. He had the strength and beauty that sometimes come to flower in Indians of low birth. When that strange race nears the dust and is condemned as untouchable, then nature remembers the physical perfection that she accomplished elsewhere, and throws out a god—not many, but one here and there, to prove to society how little its categories impress her.

These aren’t unintelligent remarks, but they are racist.

Galgut brings complexity and compassion to his Morgan. Even though Morgan felt stifled by his suburban mother back in England, from the remove of India she seems more tolerable:

Time and distance had softened her outlines, so that he longed for her without ambivalence. Their alliance was occasionally sisterly, pinned together with cackling and gossip, and these moments had strengthened with her absence. Despite their difficulties, she had always been a good traveling companion and he imagined her beside him now, keeping pace in a rickshaw.

With Masood, nothing of value is happening. “They talked about food, or the weather, or problems of justice, but they didn’t speak about anything that mattered. Everything was jest, or chatter, or deflection, and all the while the days were passing.”

Back in England Morgan meets Edward Carpenter, the apostle of simple living close to nature and of sexual freedom. Carpenter lives with a younger, working-class man—quite fearlessly, since the memory of the dire Oscar Wilde trial was still in the air, and homosexuals could be arrested. Morgan has read Carpenter’s pamphlets on “homogenic love.” Carpenter’s lover, George Merrill, touches Morgan on the lower curve of his back. That touch inspires Maurice. When a university friend, Hom, reads the manuscript, he says:

Advertisement

What you want is to live with a man in a happy home. But you don’t know how trivial it is. Marriage is emblematic of modern life. The way men and women are together—it’s a silly business, it has no nobility.

This could well be a remark addressed to the contemporary gay fight for marriage equality.

D.H. Lawrence was a more perplexing figure. Although Forster fiercely admired his fiction, he felt that Lawrence disapproved of him, and that he would never want to live in the Utopia that Lawrence was scheming to develop. In real life Forster esteemed both Melville and Lawrence, visionary novelists so unlike him but both gifted with what he called (in Aspects of the Novel) “prophecy,” the knack for seeing mystical meaning in ordinary things. In A Passage to India Forster himself became prophetic in interpreting the echo heard in the Marabar caves.

Forster wrote two short books inspired by his love for Masood and Mohammed, though he scarcely mentions either man. The Indian book was The Hill of Devi, a charming account of his life at court in 1921 as the private secretary of the maharaja of Dewas Senior, a tiny principality. The ruler is a small, ugly, saintly man utterly consumed by his love for Krishna. Some of the most luminous pages Forster ever wrote are about the noisy, endless rituals devoted to the birth of Krishna. Pages of letters home reflect at once his very English impatience with the irrational and the superstitious, as well as his wholehearted generosity of spirit in understanding and absorbing another culture.

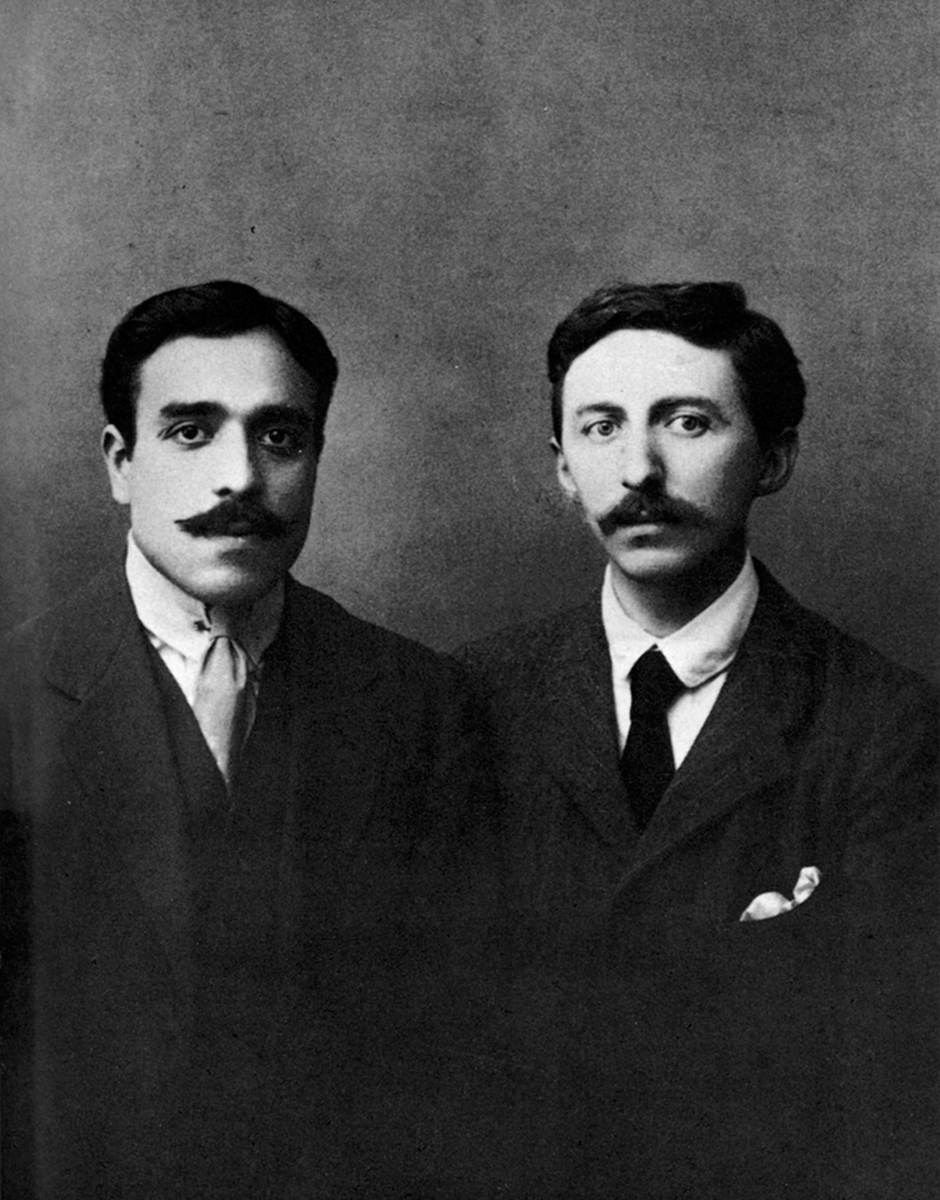

The book about Alexandria, Pharos and Pharillon, is less impressive, mainly because it is a rehash of the history and legends attached to the great Egyptian city. Perhaps its most remarkable contribution is a last chapter virtually introducing C.P. Cavafy to English readers, though typically Forster writes only of Cavafy’s historical poems and doesn’t mention the ones that deal with homosexual love and passion. In Arctic Summer, however, Cavafy ultimately reads to Morgan one of his gay poems:

It was an account, in the first person, of an erotic encounter on a bed in a dingy room above a squalid street. There was a delicacy to the language that refrained from being too specific, too physical, and yet it was obvious that the poet was writing down a memory, or perhaps a longing.

Morgan envies what he imagines are Cavafy’s rich erotic adventures, or at least those of the young men in his poems. Morgan’s

loneliness was now so big that it had become his life. With it there had grown a sort of finicky distaste, so that if the experience for which he longed had actually been offered to him, he feared he might refuse it.

No worry—right after this thought he has a charged encounter with a British soldier on the beach. And then he meets his eighteen-year-old tramway conductor, with whom he has real sex in a bed. Sex and friendship, though Mohammed is not a “minorite” (Morgan’s word for his vice).

Galgut, a South African, is one of the best writers in the English-speaking world. The Good Doctor and In a Strange Room, two earlier works both shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize, are as mysterious and unsettling as a play by Harold Pinter and as well written (if not as funny) as a Beckett novel. If there is a hint of male–male attraction in both books, it is nearly effaced, rubbed out, like a word in a painting by Cy Twombly. Arctic Summer marks a decisive change. It is not mysterious, it follows the main lines of Forster’s life faithfully, and homosexual desire in it is quite explicit.

It is even less unusual formally than A Passage to India, which orchestrates complex social scenes in which little happens (what Katherine Mansfield derisively called Forster’s practice of “warming the teapot”), switches from a dozen different points of view (whereas Arctic Summer stays faithful to Morgan’s perspective alone), dramatizes the mutually uncomprehending Indian and English cultures, and interpolates wise interpretations of character and meaning in much the way a writer like Elizabeth Bowen might.

Forster disliked Henry James’s doctrine of limiting the point of view to one or two characters and of eschewing authorial generalizations. Forster wanted the freedom and authority to write of a minor character:

He had read and thought a good deal, and, owing to a somewhat unhappy marriage, had evolved a complete philosophy of life. There was much of the cynic about him, but nothing of the bully….

In Arctic Summer observations are fully grounded in character and situation and nothing is handed down ex cathedra. When Morgan, back in England, learns that Mohammed is dying from a recurrence of tuberculosis, he thinks:

There was nothing to be done. Mohammed’s life had been touched, but not changed, by Morgan’s, and his fate had been shaped by his station. Race and class were a kind of destiny; very little could dent them. Morgan himself had been decanted back into the vessel that had made him.

Where Galgut does echo Forster is in the subtle beauty of the language, in verbs such as “dent” and “decanted.” Anatole France once said that the best style was one that departed from the conventional only enough to make it striking; in Arctic Summer Galgut seems to be obeying this placid, unflashy aesthetic. Like Tóibín in The Master, he has decided not to compete stylistically with his subject.

Just as middle-class bigots often pretend to be “bored” by what really shocks them, so prudish intellectuals object to an “overemphasis” on a biographical subject’s sexuality, especially if that sexuality is “minorite.” Critics will complain that a biographer has “turned” Proust, say, or Frank O’Hara into a homosexual and not given enough space to his work. Galgut is to be applauded for showing that homosexuality was an integral part of Forster’s writing—and of his forty years of silence, once he realized he could not write about it.