Toward the end of In Jackson Heights, Frederick Wiseman’s wonderfully dreamlike new film—a seeming celebration of a neighborhood in Queens that its city councilman calls “the most diverse community in the whole world”—we see two Cuban grandmothers singing, with great joy and abandon, “Yo Vendo Unos Ojos Negros.”

I sell a pair of black eyes

Who wants to buy them from me?

I sell them for being bewitching

Because they paid me badly.

One woman is toothless, both women wear baseball caps, and as they sing verse after verse—about sorrow, fading flowers, lost love—their voices grow stronger, their gestures more exuberant. The scene shifts and the women continue to sing as we look down on streets that have, throughout the film, been alive with shoppers, street vendors, musicians, gardeners, and people of all ages, colors, and ethnicities. It is nighttime, and the streets, well lit by lampposts and flashing neon store signs, seem eerily peaceful. A subway train floats toward us on an elevated track, an ambulance makes its silent way through an intersection, the camera rises, and for the first time we see the world that exists beyond Jackson Heights. We notice a looping necklace of lights—the Queensboro Bridge—and beyond the bridge, the Manhattan skyline. Then, low on the horizon behind the skyline, fireworks explode soundlessly in the dark sky.

It is the Fourth of July, and while festive bombs burst in air to celebrate the nation’s independence, the movie ends. Under the film’s credits, the grandmothers go on singing “Cielito Lindo,” which urges us to make the best of a bad situation. The moment is rich in playfulness and is informed with irony, as is the rest of this most richly textured and sumptuously beautiful of Wiseman’s forty documentaries.

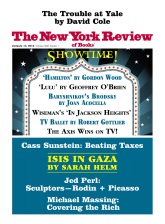

In Jackson Heights may be seen, as The New York Times said, as “an ode to the immigrant experience”—a “love letter from Frederick Wiseman to New York and its multi-everything glory.” The film has what Wiseman called the “absolute visual feast of colors” given him by the clothes the new immigrants in Jackson Heights wear and the wares they sell, and it gives us scene after scene of the community’s diverse populations—gay and transgender groups (whose members are themselves remarkably diverse), newly arrived immigrants (mostly Latino, but also Bangladeshi, Pakistani, South Asian), as well as Irish, Italian, and Jewish residents who settled in Jackson Heights a generation earlier. The persistent attention to sorrow, despair, and frustration shows an evident part of the truth—one revealed with grace and veracity in the lives of the people we meet.

“For most films,” Wiseman writes in his autobiographical essay “A Sketch of a Life,” “I only visit for a day or two before the shooting starts…. I am always afraid that something really interesting will happen while I am there doing ‘research’ and that I will miss it for the film, which would make me very sad.” In editing down 120 hours of “research” to three hours of film for In Jackson Heights, he seems to have missed little. Wiseman writes:

I never change the order of the events. The edited version has to appear as if it took place the way the viewer is seeing it, when, of course, it did not. In this sense the edited version is a “fiction,” because, if it works, it creates the illusion, however momentary, that the scene originally occurred in the form used in the final film.

Although Wiseman’s films are all based on “un-staged, un-manipulated actions,” the editing, he said in an interview, “is highly manipulative and the shooting is highly manipulative.”

A ninety-eight-year-old woman, in a group of senior citizens at the Jackson Heights Jewish Center, laments that she lacks the nerve to kill herself. “What am I doing here?” she asks, and answers, “Nothing.” A woman at her table points out that, since she is rich, she could pay people to entertain her. “Money talks,” this woman says. “If you pay, you can find everything. Everything. Even a boyfriend.” The women laugh.

A middle-aged man who has owned a business for twenty-two years talks about how he and fifty other small businesses are being driven out by developers. “We have,” he says, “no political representation.” Their state senator is in jail for stealing taxpayer money; their state representative is involved in scandals; their representative in the Congress in their native country of Colombia is “a shameless man who is being investigated”; and other politicians show up only when campaigning for office. Another business owner asks how he and others like him can compete with the new Gap store, which opened with a 70-percent-off-everything sale. How will they and their families survive? How will women who have been waitresses their whole lives find new jobs when big corporations want to hire only bonitas—pretty young things?

Advertisement

A worker wearing a New England Patriots jersey talks at a New Immigrant Community Empowerment meeting about working more than eight hours a day without even lunch or a glass of water. “If you think about it,” he says, “the basic question is: are we human beings, aliens, or what?” And then: “We realize even as Latinos, we aren’t treating each other decently. Employers can be Latinos and from everywhere!”

An immigration counselor tells a woman hoping to keep her child from being adopted that “there are very few legal possibilities for immigrants,” and suggests she look into a group that takes “deferred action for childhood arrivals.” In Joan of Arc Church, a priest reminds his congregation that “original sin…thrives in the world” and that “we as human beings tend to selfishness. And selfishness leads us to actions that are excessive…because we are looking to fill our inner emptiness.”

As if to illustrate the priest’s message, a young Mexican talks to a large group about working a sixty-to-sixty-five-hour week as a pizzeria cook without being paid overtime. A man asks, “out of curiosity,” where the owners are from. The young man doesn’t understand the owners’ language, he says, but he observes that they pray three times a day, and the group concludes they are Muslim. “No matter where they are from, or their color,” an older woman interjects angrily, “whether it’s green, yellow, or red, it’s discrimination and wage theft!”

A younger woman says, “We have traveled the entire world. No matter whether you are Chinese, American, Dominican, Colombian, Argentinian…we see all the countries here. And we see employers who steal wages even from their compatriots.” “So please,” she adds, “When a person wants to steal money from their workers, he doesn’t care if they are from his country or his family. If his heart is set on making an extra dollar on the worker’s back, he will.”

Although in meeting after meeting we see dozens of people talk passionately about joining together to fight discrimination, exploitation, and gentrification—to keep out developers, rent gougers, and stores such as Gap and Home Depot—except in gay and transgender meetings, we never see individuals from different ethnic groups talk with one another. Nor do we see any evidence that all the talk about workers joining together—in “unity,” as community organizers keep saying—makes any difference. The same can be said for small business owners. By the end of the film, cruising along streets previously dominated by Spanish and Arabic store signs, we notice the presence of Starbucks, Payless, Cohen’s Fashion Optical, J&B Electronics, and Gap.

The councilman for Jackson Heights, Daniel Dromm, addresses a gay community breakfast—a meeting to plan the neighborhood’s annual Gay Pride parade that will commemorate the murder of Julio Rivera, a gay man whose case, twenty-five years ago, was assigned to a detective who was on vacation for two weeks. Dromm talks at length about what makes Jackson Heights, where 167 different languages are spoken, unique. When he lists nationalities that will be cheering at the parade—Ecuadorians, Colombians, South Asians, Bangladeshis, Indians, Irish, Dutch, Germans, Dominicans, Maldivians, Maltese—the audience erupts in applause.

Dromm has been holding forth in the neighborhood’s Jewish Center, and immediately before we hear his praise of ethnic and cultural diversity, we see a congregation of Muslim men, and—the first words we hear in the film, in Arabic—hear them at their morning prayers: “In the name of Allah the Merciful. Allah is to be praised….”

At a large meeting of new immigrants, a woman describes the life-threatening fifteen days it took her daughter to cross the Rio Grande. The woman’s hope and courage are palpable; so is the dedication of those who help new arrivals like this woman and her family become citizens and find work. We see two scenes where people receive food on bread lines. Yet the moments that tell of disappointment, loss, and defeat are belied, visually, by the pervasive, startling brightness of a film, shot mostly in midday spring and summer sun, that records the dazzling colors, sounds, and textures of an extraordinary range of cultural and social groups—with much attention to their food, flags, clothing, storefronts, signs, and, especially, to their faces.

Wiseman and his cinematographer, John Davey, pay close attention to tomatoes and squash in an open market, kitschy Catholic and Buddhist ceramic statuary, the contrasts of cloth and skin on the bodies of young women who wear burkas or shimmering belly-dancer skirts. I can think of no film that lingers on the faces of so many people of varying ages and nationalities, no film so alive to the tangible particularity of such a wide range of humanity, so that, by the film’s end, we seem to have been visitors to a place where the variety of the entire world is present—all in one New York City neighborhood less than a half-mile square.

Advertisement

“My films are about institutions, the place is the star,” Wiseman has written. He has made films about particular communities—Aspen; Canal Zone; Belfast, Maine—and dozens of films, beginning with his first, Titicut Follies, about institutions. They include Hospital, Welfare, Juvenile Court, Basic Training, High School, etc. “The cumulative effect is to try to provide an impressionistic portrait, obviously incomplete, of some aspects of contemporary American life as reflected through institutions important for the functioning of American society.”1 His films never have a narrator, never stage interviews, and use only available light. They are powerful studies of “injustice, poverty and cruelty,” A.O. Scott has written in the Times, but they never “preach or explain.”

In Jackson Heights—the sixth film in the past seven years by the eighty-six-year-old Wiseman (another, about the New York Public Library, is in progress)—has all the virtues for which his films have been celebrated, but in larger ways. There are lush scenes set in a club where gay and transgender people congregate, and where a man, standing on a bar under flickering strobe lights, does a splendid striptease, but we also get a sense of the history of Jackson Heights, and implicitly, of the history of immigration in the United States. The film reminds us how a new generation of immigrants replicates the stories and struggles of earlier generations.2

Instead of giving us an in-depth portrait of how a single institution works, as he does in films such as Welfare, Hospital, and Near Death—films that never leave the single building in which each institution is housed—Wiseman gives us portraits of a variety of institutions in Jackson Heights—bars, stores, diners, butcher shops, nail salons, barber shops, and a politician’s office. In a Wiseman film, Errol Morris wrote, “redundancy is the spice of life.” But Wiseman is able to show affinities without being redundant. Thus, when near the film’s end we see a boy joyfully taking a freshly groomed puppy into his arms and stroking its chest, we may recall an earlier scene in a slaughterhouse where live chickens hop around on blood-drenched floors, and a Muslim man, holding chickens close to him, chants prayers before slitting their throats.

Deep into the film, we see two boys, at dusk, sitting forlornly on a curb, a small pail of bunched flowers for sale beside them. We may then recall earlier scenes, where bright bouquets of flowers—electric-blue tulips, graceful white lilies, shamelessly bold sunflowers—fill the screen. In scene after scene and image after image, In Jackson Heights reveals not only different social identities of the people who live in Jackson Heights, but also—what gives the film its remarkable authenticity and poignancy—a sense of their mystery and complexity as individuals.

The camera is particularly attentive to the ways people physically touch one another. Again and again, we are aware of hands, whether grooming a puppy, threading a woman’s eyebrows, massaging a woman’s face, cutting a man’s hair, inscribing a tattoo on an arm, knitting baby clothes, or slitting a chicken’s throat. We see a woman holding an outsized ceramic statue of the baby Jesus, one of whose arms is broken off—amputated at the shoulder—and carrying it as if were her own wounded child.

Through such images, and in the movement, often ironic, of one scene and image to the next—in contrasts, confluences, and recurrences that seem phantasmagoric—Wiseman invites us into a world that is both familiar yet always unexpected. We cut from a Gay Pride parade to a pet store, from a transgender counseling session to a Holocaust memorial service, from a protest march along sunlit streets to a dimly lit halal slaughterhouse, from hundreds of garishly illuminated articolos catolicos to a belly-dancing class, so that we seem to be observing streets, stores, offices, and meeting places in a city famed for its grit that have been conjured up by the ghosts of Cocteau or Fellini. Wiseman and Davey can make the flaking paint and rust on the girder of an elevated subway station, the headlights of an oncoming Q33 city bus, or the infected toe of a woman seem enchanted.

If Wiseman is a fantasist—as he claims—he is one in the way that nineteenth-century novelists were fantasists. In the novels of Dickens, Hardy, Flaubert, and Balzac we feel we can experience the way people actually lived in the nineteenth century. So it is with In Jackson Heights, and with Frederick Wiseman’s films. If now, a decade from now, or a century from now, people will want to know and understand how people lived, worked, and played during the last decades of the twentieth century and the early decades of the twenty-first, they could do no better than to go to the forty-three films that make up Wiseman’s cinematic Comédie Humaine.

This Issue

January 14, 2016

ISIS in Gaza

How to Cover the One Percent

A Ghost Story

-

1

Wiseman’s first thirty-six films were set in the United States. Since then he has made several films set in Europe. “There have been four French films,” he writes, “each on a subject that was not possible in America. For example, there is no American theater or ballet company with the continuity, tradition, and history of the Comédie-Francaise or the ballet company of the Paris Opéra.” His most recent film, National Gallery (2014), was set in London. ↩

-

2

In several otherworldly scenes where no one speaks, we visit handsome homes and gorgeously landscaped lawns that belonged to people who came to Jackson Heights following World War I. The largely expensive developments with gardens excluded Jews, African-Americans, Greeks, and Italians, and offered its residents luxury living in what were the very first “garden apartments” in America. ↩