About the origins of modern sculpture there is a general consensus. The story begins with Auguste Rodin, who died in 1917 at the age of seventy-seven. Rodin was a mythomaniac in the perfervid Romantic style of Victor Hugo and Richard Wagner. He was also a connoisseur of particularities and eccentricities, who sometimes preferred the fragment to the finished work. He struggled to imagine and on a couple of occasions succeeded in creating the monuments that nineteenth-century statesmen, industrialists, and intellectuals demanded for their official buildings and public squares. All the while, he could see that the Apollonian order embodied by those monuments was giving way to increasingly Dionysian forces, which he celebrated near the end of his life with a small study of Nijinsky, the mesmerizing dancer many embraced as the avatar of a new age.

Rodin, with his zigzagging enthusiasms, may have been the first sculptor to conceive of the monument in ways that unmade the monument. He set the stage for the twentieth-century sculptor’s conflicted allegiances to grandiosity and intimacy, as well as what many have come to see as modernism’s embrace of ambiguity. Although Rodin was capable of placing an expressive figure on an imposing base, as in his beguiling salute to the seventeenth-century landscape painter Claude Lorrain, often he aimed to destabilize the monument, suggesting with The Burghers of Calais that heroic figures might have no need for a pedestal and transforming the imposing, cloaked figure of Balzac into a mountainous talisman, a primordial plinth. In Rodin’s anti-monuments we see ambitions and equivocations that lead in ways direct and indirect to Constantin Brancusi’s Endless Column, Vladimir Tatlin’s Monument to the Third International, the various versions of Pablo Picasso’s Monument to Apollinaire, Alberto Giacometti’s towering Women of Venice, Alexander Calder’s immense stabiles in Spoleto, Montreal, Mexico City, and Chicago, and Donald Judd’s one hundred mill aluminum boxes in Marfa, Texas.

The reopening in Paris of the Musée Rodin—all its subtleties and surprises only sharpened and freshened by a three-year renovation—is one of a series of events occurring almost simultaneously in cities on two continents that, if taken together, offer new opportunities to explore Rodin’s power and influence as they resonate through several generations. We are at a moment in the arts when historical reckonings, involving as they do considerations of precedent, genealogy, and chronology, can too easily be dismissed as reactionary gestures, canonical considerations to be tossed aside. There is all the more reason to press for a reconsideration of the tradition that begins with Rodin.

While no three or four exhibitions will enable us to survey the entire story of modern sculpture, we can certainly trace some of the seismic shifts in the modern artist’s experience of the third dimension by exploring “Picasso Sculpture” (at the Museum of Modern Art in New York), “Alexander Calder: Performing Sculpture” (at Tate Modern in London), and the retrospective devoted to Frank Stella (at the Whitney Museum in New York). Stella, still in his twenties when he was first celebrated as a painter, has more and more over the years experimented with sculptural elements and by now produces what can only be called sculpture. In his work he renews an age-old argument about the relative values of painting and sculpture, a debate that he addressed, albeit indirectly, in his brilliant Norton Lectures, presented at Harvard in 1983–1984 and published as Working Space.

Rodin, whose work often strikes sophisticated museumgoers as armored and ostentatious, was a believer in the Great Tradition who recognized all tradition’s dangers—the prepackaged emotions, the schematic thinking, the programmatic solutions. His megalomania can be off-putting, especially now, when the megalomania of Koons, Hirst, and their kind has so trivialized the very idea of a Great Tradition. There is no question that Rodin is not an artist who is easy to love, at least not unreservedly. This helps to explain the dramatic shifts in his reputation that have occurred in the nearly one hundred years since his death.

The last great revival of interest in his work was in the 1960s. The reason is not difficult to discern. It was a time when many astute observers of the contemporary scene were arguing that new sculpture by artists ranging from David Smith to Donald Judd was outstripping new painting in originality and importance, a turn to the third dimension chronicled in a legendary exhibition, “American Sculpture of the Sixties,” at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 1967. Rodin looked to be a progenitor. Could it be that the times are now ripe for another renewal of interest in Rodin, whose engagement with tradition may prove to have been as ambiguous, contradictory, and conflicted as our own?

Advertisement

We cannot begin to understand Rodin without looking back a generation, to an outpouring of beautifully nuanced thinking and writing about his work by artists, critics, and scholars. Albert Elsen’s monograph on Rodin was published in 1963—significantly, by the Museum of Modern Art, at the time of a major retrospective. For over a decade after that there appeared a group of books on modern sculpture that have still not been superseded—and each begins with Rodin or at least celebrates him as a seminal figure. These include the critic Herbert Read’s A Concise History of Modern Sculpture, the historian Rosalind Krauss’s Passages in Modern Sculpture, the sculptor William Tucker’s The Language of Sculpture, as well as Beyond Modern Sculpture by the sculptor Jack Burnham and What Is Modern Sculpture? by the historian Robert Goldwater.

For Rosalind Krauss, the essence of Rodin is his “belief in the manifest intelligibility of surfaces.” She admires his “lack of premeditation, a lack of foreknowledge, that leaves one intellectually and emotionally dependent on the gestures and movements of figures as they externalize themselves.” Krauss was by no means alone in her emphasis on Rodin’s tactile spontaneity. William Tucker, a writer with none of Krauss’s taste for theory, also locates Rodin’s essence in his surfaces, in the modeling that signals

a total and violent break with the past, achieved through the uninhibited manipulation of substance to the point at which the intelligible communication of form would break down, were it not for the figure as vehicle. Clay is here asserted for what it is: soft, inert, structureless, essentially passive, taking form from the action of the hands and fingers.

So Rodin, in these commentaries composed half a century ago, emerges as an artist in revolt against classical stability.

With Rodin, surfaces become changeable, unpredictable, roiled, coruscated, with a life of their own. Rilke—who arrived in Paris in 1902 to write a monograph about Rodin, admired the artist immensely and spent a good deal of time at his side, eventually working as his secretary—was the first to declare that “the fundamental element of his art [was] the surface.” The poet wrote of “this differently great surface, variedly accentuated, accurately measured, out of which everything must rise,” arguing that it was “the subject-matter of his art.” Rodin rejected the sense of completeness—of the figure as a whole, perceived all at once, from head to foot—in favor of the figure that is masked or shrouded, or barely separated from the block of marble from which it emerges, or only a fragment, the body disembodied, with the part (a hand, a foot, a torso) standing in for the whole. This breakdown of the classical figure suggested entropy—a move toward disorder—but also possibility, a dismemberment of the heroic body that brought not death but renewal.

For much of the past hundred years the Musée Rodin has been a Parisian landmark, embraced by casual tourists as well as ardent Francophiles. Housed in the Hôtel Biron, an eighteenth-century structure that Rodin occupied in his last years, the museum was Rodin’s idea, with the French state agreeing to turn the building into a museum as a condition of Rodin’s gift to the nation of his life’s work. As for the garden full of sculpture that surrounds the house, it may have for Parisians some of the same enduring charm that the sculpture garden of the Museum of Modern Art holds for New Yorkers.

Even during Rodin’s lifetime, visitors to his various studios were awestruck by the profusion of his work. Rilke, visiting his studio in suburban Meudon, felt nearly blinded by the play of bright sunlight on statues in plaster. And he wondered at the extraordinary array of sculpted hands and other body parts, which Rodin moved around freely, incorporating them in different figures, or creating unconventional works such as The Cathedral, with two hands lightly held together, suggesting a prayer.

Much of the fascination of the Musée Rodin has always resided in the overload of works, with visitors left to discover things for themselves. It is the genius of this renovation, overseen by the museum’s director, Catherine Chevillot, that it brings a new clarity and brightness to the Hôtel Biron without sacrificing any of the museum’s offbeat magic.

Although some early landscape paintings by Rodin as well as works by Monet and Van Gogh that he collected serve to remind us that Rodin came of age with the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists, he stood somewhat apart from the embattled confrontation with nature that shaped painting from Courbet and Manet to Cézanne and Matisse. It is true that The Age of Bronze, the standing male nude that first established his reputation when it was exhibited at the Salon in 1877, struck audiences as astonishingly naturalistic, so much so that Rodin was accused by some of having cast the figure from life. But even in The Age of Bronze, Rodin’s struggle was not so much with the exigencies of nature and perception as with the classical ideal of the human figure as a stable form. What was modern in Rodin’s work grew out of his never-ending argument with the poise and balance-within-imbalance of the Greco-Roman ideal, which he saw as already profoundly unsettled by Michelangelo’s hyperbolic achievement. If modern painting is an argument with naturalism, modern sculpture, as it began with Rodin, is an argument with classicism.

Advertisement

Rodin’s development was cyclical, a perpetual reconsideration of the human presence. The commission he received in 1880 for The Gates of Hell, bronze doors for a proposed museum of decorative arts, set him on a decade-long effort to encompass Dante’s Divine Comedy in a single vast composition, and well after the original commission had faded he was exhibiting elements of the composition—The Thinker, The Lovers, Ugolino—as freestanding works of art. Beginning with a composition of rectangular bas-relief units inspired by Ghiberti’s Baptistry doors in Florence, Rodin pushed farther and farther into a baroque symphonic composition, a disorder of swirling, entangled figures that left all practicalities of door and doorway behind. Cluttered, coagulated, the doors became a work that could never be finished, its mingled influences from Hellenistic sculpture, Dante’s Divine Comedy, Michelangelo’s Sistine ceiling, and Art Nouveau’s swirling patterns a combustible mix that generated, in ways both direct and indirect, the ambiguous, dreamlike drama of later compositions large and small.

This artist who spent years working on monuments to Hugo and Balzac was, like those titans of French literature, looking for a modern cosmology, the pieces of a puzzle that would perhaps never cohere, an epic in parts drawn from a fragmented universe. It is no wonder then that what one takes away from the Musée Rodin is less a strong impression of particular works than a more general sense of varieties of surfaces, muscular possibilities, greater and lesser levels of finish and completeness and incompleteness, the play of the imagination. All forms of movement—bending, stretching, walking, leaping, falling—are considered from a variety of angles, in many different ways. Rodin pursued a number of curious experiments, one striking example a group of works with small clay studies of men and women placed in antique bowls to create fantasies of growth and struggle, the vessel’s cool symmetry pitted against the figure’s agitated gestures. When Rodin explored a naturalistic gesture—the close embrace of The Lovers or the seated, contemplative pose of The Thinker—his goal was not quotidian truth but allegorical impact.

Rilke, whose studies of Rodin came in two parts, a brief monograph published in 1903 and a lecture presented four years later, announced in his lecture that he did not intend “to speak of people, but rather of things.” This strikes me as the key that can unlock not only the art of Rodin but modern sculpture more generally. Rilke ruminated on the nature of things, urging his listeners to think back to some object in their childhood that meant a great deal to them, and consider the “urgency, the particular, almost desperate earnestness all things have,” what he called “an unimaginable beauty,” what he finally referred to as “the thing itself, which evolves irrepressibly in human hands, [and] is like the Eros of Socrates, it is the daimones, between god and man, not necessarily beautiful itself, but pure love and longing for beauty.”

Remove the filigree of fin-de-siècle spiritualism from Rilke’s remarks and they provide a valuable guide to the variety of objects on display in “Picasso Sculpture,” the exhibition that fills the entire fourth floor of the Museum of Modern Art. Certainly the roiled surfaces of Picasso’s work in plaster and bronze—from The Jester (1905) to the Man with a Lamb (1943)—owe much to Rodin, whose work Picasso knew well during his early years in Paris. But there may be more that we learn about Picasso from Rilke, whose Fifth Duino Elegy was inspired by Picasso’s Family of Saltimbanques and who wrote movingly about Cézanne as well as Rodin.

Picasso’s Cubist sculpture—the Glass of Absinthe (1914) shown at MoMA in six differently painted versions, and the abstract guitars made over a decade in cut, bent, and sometimes painted sheet metal—confounds any conventional notion of sculpture, presenting us with a glass from which we cannot drink and a series of guitars that cannot be played. The work of art becomes a conundrum, an unreal object set in the real world. Sculpture, in Picasso’s hands, has given way to things—precisely what Rilke saw happening in the art of Rodin.

Picasso was not the only artist who embraced sculpture’s new status as enigmatic object. Brancusi, in compositions such as Timidity (1917) and The First Cry (1917), transformed elaborate wooden bases into inscrutable, virtually independent works of art. Both Picasso and Brancusi recognized, at the core of the classical tradition, certain totemic and fetishistic impulses. The art of Africa and the South Seas, a discovery in Picasso’s circles in the first years of the new century, suggested alternative traditions, all the more powerfully because they were so utterly unfamiliar. When the Galerie Ratton in Paris mounted a famous exhibition of three-dimensional works in 1936, the title was “Surrealist Exposition of Objects,” the word “objects,” like Rilke’s “things,” suggesting that the works on display by Picasso, Marcel Duchamp, Jean Arp, Alexander Calder, and a host of other artists had what Rilke referred to as “an unimaginable beauty” and André Breton would have described as a “convulsive beauty.”

Among the avant-garde there was a growing belief that new terminologies might be needed to describe unprecedented forms of three-dimensional expression, among them the abstract wire constructions of Calder. Duchamp dubbed Calder’s kinetic works mobiles, Arp suggested that his static works be called stabiles, and Calder himself in his later years invariably referred to his creations as objects rather than sculptures. This rechristening of art’s third dimension culminated with Donald Judd, who in the 1960s dubbed many of the contemporary works that interested him “specific objects”—which might be regarded as a plainspoken American way of continuing Rilke’s Germanic talk of “the thing itself.”

“Picasso Sculpture,” which will travel to the Musée Picasso in Paris, is among the largest exhibitions of the artist’s work in three dimensions ever held, and it is no surprise that it has been received with rapturous reviews in New York. Through much of his life, Picasso was reluctant to exhibit his sculpture in public—most of it remained in his own possession—and it was only in the mid-1960s, when he was in his seventies, that he agreed to make generous loans to retrospectives in Paris, London, and New York. MoMA has pulled out all the stops for what is the second major exhibition of Picasso’s sculpture in this country; the first was also mounted at MoMA, in 1967. The fourth floor of the museum, generally devoted to the permanent collection, has been emptied and filled with Picassos, the installation so spacious as to feel almost stark, an impression increased by the absence of identifying labels on the works (a brochure available at the beginning of the show contains this information).

While Ann Temkin and Anne Umland, the curators in charge, probably meant to create a dramatic atmosphere with this stripped-down presentation, I am sorry to say I find something slack in the installation, some reluctance to shape this highly variegated body of work. This is an exhibition without a clear rhythm or clear climaxes, the triumphs and near misses and misses hardly distinguished. The curators’ idea may have been to stand back and allow the work to speak for itself, but the work speaks in so many voices and dialects that the ultimate effect of all the white walls and evenly sized and scaled spaces is to muffle Picasso’s multidirectional assault on museumgoers. For Picasso—who discovered in African and South Seas masks and statues an unnerving antinaturalistic power to set against his birthright, which was the Greco-Roman tradition’s unshakable equanimity—sculpture would always be a speculation, a gambit, a dare.

There is something almost lunatic about Picasso’s profligacy with methods and materials. The catalog of the MoMA show, with its detailed chronological narrative of his sculptural pursuits, is a brilliant piece of work that brings his careening, unpredictable, stop-and-start production into focus. Unfortunately, when it comes to the exhibition itself, the curators have failed to honor the distinctive, highly variegated qualities of Picasso’s work with clay, plaster, cast bronze, welded metal, scrap metal, sheet metal, metal rods, carved wood, wood constructions, cardboard, paper, stone, glass, not to mention found objects of all kinds. The masterpieces—the openwork Figures made as studies for the Monument to Apollinaire, the scrap metal Women in a Garden, the heads of Marie-Thérèse Walter in plaster and bronze—are insufficiently distinguished from what amount to masterful jeux d’esprits, such as the boxed, sand-covered assemblages done in the summer of 1930 or the etched stones and glass figurines from the 1940s. I find myself wondering if Temkin and Umland clearly saw the difference between Picasso in dead earnest and Picasso when he’s just kidding around.

Picasso was the most dialectical of artists, and when it came to sculpture he was forever arguing with the ancient obligation to graciously represent gods and goddesses, the bizarre twists and turns of his sculpture as often as not an Olympian joke on its own Olympian origins. Consider the guitars made of sheet metal, those unplayable musical instruments, with their elegant mockery of utilitarianism. Or the openwork structure of the various studies for the Monument to Apollinaire, which skewer the solidity of the old-fashioned monument. Or the massive heads inspired by his lover Marie-Thérèse, produced at the Chateau of Boisgeloup in the early 1930s, which honor the classical ideal of gently curving volumes even as they mock those classical values by turning a woman’s face into a man’s genitalia.

Picasso was always a trickster, a clown of metamorphosis, etching stones found on the beach to create faux ancient fragments, and producing, in the old pottery town of Vallauris, the hundreds of plates, pitchers, and bowls that marshal the potter’s wheel for an Ovidian game, pitchers turned into birds, vases into women, and platters into amphitheaters on which bullfights unfold. Of course the exhibition includes Picasso’s most famous tranformations: the bicycle seat and handlebars turned into a bull’s head, and the Baboon and Young, whose head is cast from a toy car, the windshield become a pair of eyes, the car’s hood a snout.

In 1933, not long after producing his heads of Marie-Thérèse, Picasso created a series of etchings on the theme of the sculptor’s studio, a few of which hang in a hallway at MoMA, not far from the entrance to the exhibition. Here we have Picasso in his storyteller mode, imagining the atelier of a sculptor of the classical period, the artist relaxing with the woman who is his mistress and muse, the two of them together contemplating the fruits of his labor.

In at least one extraordinary image there turns out to be trouble in paradise. The artist’s muse, a naked classical beauty, finds herself face to face with a surrealist sculpture of a seated figure. She regards this grotesque vision, a collage of bizarrely knocked-together body parts, with a surprisingly cool fascination. Apparently the athletically built, bearded sculptor, although sometimes wreathed with laurel, cannot rest on his laurels. For him Pygmalion’s dream of bringing a statue to life gives way to the larger question of the various kinds of life the artist can grant to clay, plaster, metal, wood, and stone.

Like Rodin, Picasso was fascinated by Michelangelo’s Slaves, those men whose struggle for freedom is framed by the sculptor’s struggle to free the figure from the block of marble. What Picasso confronted throughout his life as a sculptor was the sure knowledge that the materials had a life of their own. The materials became his muse.

—This is the first part of a two-part article.

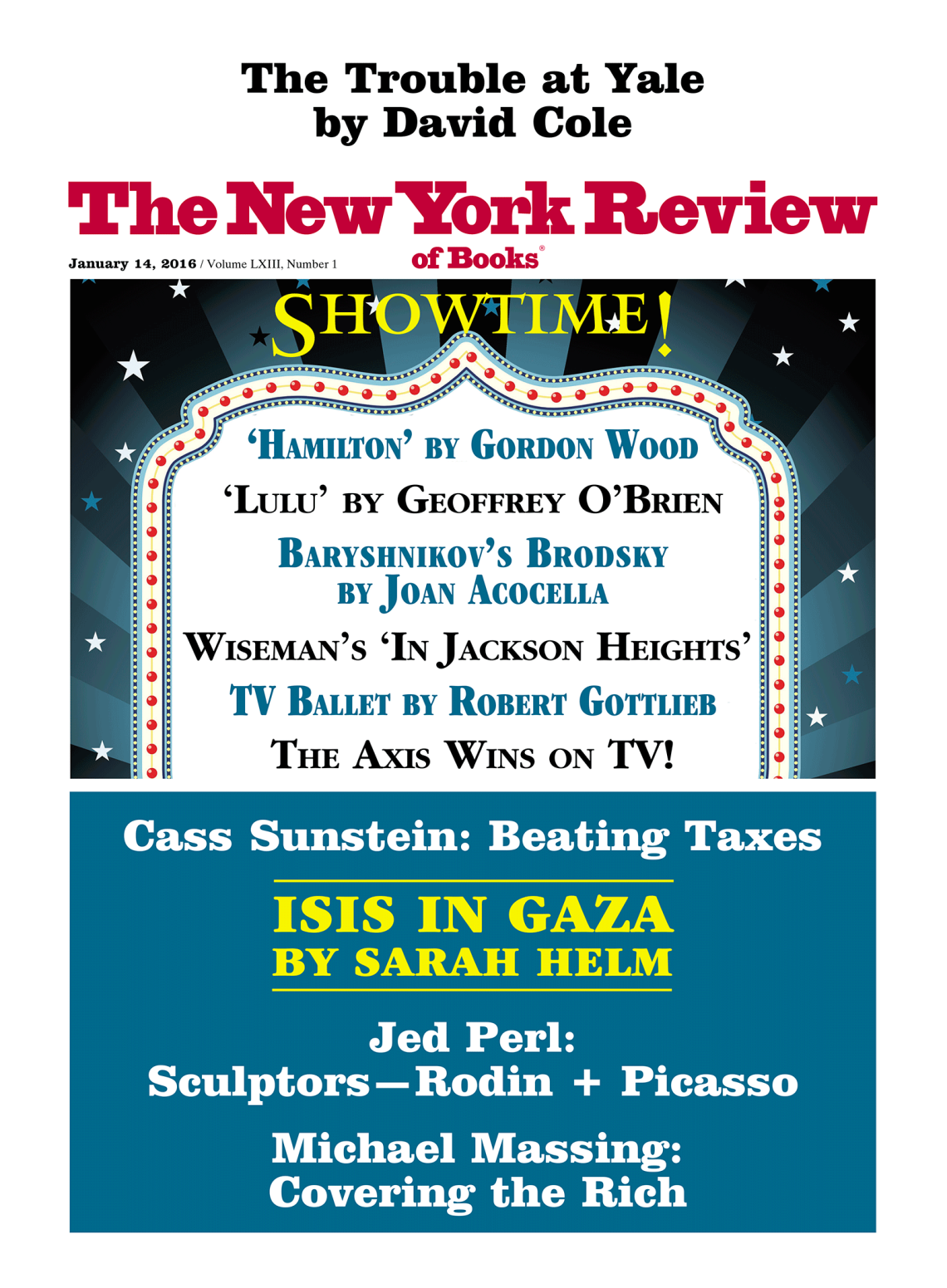

This Issue

January 14, 2016

ISIS in Gaza

How to Cover the One Percent

A Ghost Story