In October, The New York Times Magazine presented its readers with an unexpected question: “Could You Kill a Baby Hitler?” The response to the online poll was closely divided, with 42 percent of respondents saying they would indeed take the opportunity to kill Hitler when he was a baby, if provided with a time machine. Another 30 percent said no, and the remainder were uncertain. But the response to the question on Twitter, where the baby-Hitler poll became a momentary sensation, was pretty much unanimous: mockery of the entire idea, and of The New York Times for asking such a futile and unanswerable question. (“Can I use another baby as a weapon?” asked one sarcastic tweet, while others suggested that it would be more humane simply to rewrite the Treaty of Versailles instead.) Clearly, the idea of changing history to eliminate Hitler and everything he made possible—Nazism, World War II, the Holocaust—has a deep appeal to our imagination; and just as clearly, the notion is seen as a not quite respectable fantasy.

Just this blend of fascination and condescension has long greeted writers who take the premise a step further, and try to imagine an alternative history in which World War II played out differently. What would a world without Hitler have looked like? Or, what if Hitler had triumphed, leaving Germany in control of a world empire? When proposed by historians, such experiments in “alternate” or “virtual” or “counterfactual” history are usually disdained as, at best, a busman’s holiday from serious research. At worst, they are a betrayal of the historian’s calling, which is to explore what actually did happen, not to speculate about what didn’t. Novelists have more leeway to imagine alternate realities, but traditionally, their alternative World War II tales have been regarded as mere genre fiction—pulp sci-fi or mysteries.

Still, none of this resistance has prevented writers from engaging in such thought experiments. According to Gavriel D. Rosenfeld, whose study The World Hitler Never Made (2005) analyzes what he calls “allohistorical” World War II stories, “well over one hundred” of them were published between the 1930s and the end of the twentieth century—not just novels, but TV shows, comic books, and video games. And such alternative worlds are increasingly making their way into literary fiction. No longer the exclusive province of mystery writers like Robert Harris (Fatherland) and Len Deighton (SS–GB), they have also been featured in the work of Philip Roth (The Plot Against America) and Michael Chabon (The Yiddish Policemen’s Union).

Academic historians, too, are more willing to risk speculating on what might have been, as evidenced by books like Virtual History: Alternatives and Counterfactuals, edited by Niall Ferguson, and What If?: The World’s Foremost Military Historians Imagine What Might Have Been, edited by Robert Cowley. World War II counterfactuals are especially popular in such anthologies: Ferguson and Andrew Roberts portray a world in which the D-Day invasion failed, while Michael Burleigh imagines a Nazi Europe following a German victory over the US.

No book better demonstrates the changing status of alternative World War II histories than the masterpiece of the genre, The Man in the High Castle by Philip K. Dick. Dick himself, once considered an eccentric cult writer, is now in the Library of America, and The Man in the High Castle—winner of the Hugo Award for science fiction when it was published in 1963—is widely considered his greatest book. This fall, Amazon, which has emerged as an important producer of original TV programming, released a ten-episode series based on the novel, which attracted a great deal of media attention and brought Dick’s story—or something resembling it—to a wide new audience. There was even a scandal, without which no PR campaign is complete: Amazon was forced to remove its ads from the New York City subway, after decorating an entire car with American flags bearing Nazi and Japanese symbols.

The fact that the governor of New York, Andrew Cuomo, thought it necessary to take down these ads is a backhanded compliment to their power—and to the power of Dick’s premise. The Man in the High Castle imagines that, following an Allied defeat in World War II, the United States is partitioned between Nazi Germany, which controls the East Coast, and Imperial Japan, which rules the West Coast. Both the TV series and the novel follow a small group of characters in San Francisco—American subjects and Japanese rulers—as they adjust to or resist the new Axis order in the year 1962.

The crucial difference between the two versions lies in which part of this process they choose to emphasize. For Dick, the drama is in the adjustment, and so it is mainly internal—the story of how (white) Americans, so used to independence and supremacy, learn to think of themselves as subservient and second-rate. This quiet drama unfolds in the stories of Robert Childan, a dealer in collectible Americana, and Frank Frink, a frustrated would-be artist and jewelry designer.

Advertisement

Childan is overjoyed when he is invited to the home of a Japanese couple, thinking he has at last been admitted to terms of equality with the occupier. But the dinner turns out to be a fiasco, and he is humiliatingly reminded of his inferiority. Similarly, Frank tries to market his original jewelry, only to find that there is no market for it. The Japanese are interested in pilfering the American past for quaint artifacts, not in supporting living American artists. It is these kinds of slights, not outright acts of cruelty, that characterize the Japanese occupation as Dick imagines it. “We are defeated and our defeats are like this, so tenuous, so delicate, that we’re hardly able to perceive them,” Childan reflects. “What more proof could be presented, as to the Japanese fitness to rule?”

By contrast, Frank Spotnitz, the producer who adapted the series for television, focuses on resistance, which means that the action is mainly external. His version of The Man in the High Castle is a story of outlaws who try to bring down the occupying regime through a series of daring exploits. Of course, the difference is largely owed to the strengths of the two genres; unlike fiction, television must always show something happening. But the result is that the TV version of The Man in the High Castle is much more conventional and melodramatic than the book it is based on, even as the two share many characters and scenes.

The television series focuses on Juliana Crain (Alexa Davalos), a young woman whose sister, Trudy, is involved in an underground resistance movement. The main work of this movement is the distribution of samizdat newsreels, one of which Juliana watches in the first episode. Though we see it only in glimpses, it seems to portray footage from the “true” version of World War II, in which the Allies triumph. This makes it a morale-booster for the defeated and occupied America of the show’s world. But there is also an implication, which grows stronger in the season’s final episodes, that the films themselves have some kind of power to overthrow the regime and change the course of history. Indeed, if the show is renewed for a second season, we will likely hear more about the mysterious “Heisenberg device” that the Nazis are said to have developed, which seems to allow for travel between alternate realities.

For most of this ten-episode season, however, the newsreels function as a classic Hitchcockian MacGuffin. It doesn’t matter what’s in them, only that every character in the story is after them. When Trudy is shot by the Japanese police in the first episode, she hands off the film to Juliana, thus involving her willy-nilly in the resistance. Juliana undertakes a trip to the “neutral zone,” a strip of territory in the former mountain states that serves as a buffer between the German and Japanese empires. Here she encounters Joe Blake (Luke Kleintank), a handsome young truck driver who also claims to be in the resistance—but who is actually, the viewer knows, an undercover Nazi spy, sent from New York to recover the film for Hitler.

Meanwhile, back in San Francisco, Juliana’s boyfriend, Frank Frink (Rupert Evans), is dragged in by the Japanese police and questioned about her whereabouts. Because Frank is part Jewish, he is in danger from the Japanese government, which has adopted Nazi-style racial laws. In one of the series’ most powerful, if manipulative, scenes, Frank’s sister and her two children are held hostage in order to force him to give up his secret. When he refuses to do so, they are gassed, in a chamber made to look like an ordinary waiting room.

This loss drives Frank to seek revenge: getting his hands on an antique Colt pistol, he plans to assassinate the visiting Japanese crown prince as he gives a speech. Before Frank can fire his gun, however, another shot rings out and the prince falls down wounded—a scene cleverly designed to evoke memories of the Kennedy assassination, with the mysterious multiple plotters who were alleged to have been involved. Now Frank and Juliana are both on the run; they must figure out a way to recover the film, help the resistance, and escape San Francisco before the Japanese police capture them.

As with most TV thrillers, however, the details of the plot do not matter much in The Man in the High Castle. There are the usual improbabilities and illogicalities, with complication piled on complication—in addition to the Japanese and the SS, the lovers must contend with psychopathic bounty hunters and Yakuza gangsters. Lest we lose sight of the grimness during all this excitement, the actors remain permanently doleful and soft-spoken, and the art direction conspires in setting the depressive mood. Every bold color has apparently disappeared from occupied America, and every single character is dressed in a tastefully muted shade of brown or blue. This palette is so insistently maintained that it becomes an affectation, though it pays off in the final scene of the last episode, when color is suddenly restored in a striking coup de théâtre.

Advertisement

These attempts to externalize the mood of defeat only underscore how well Dick establishes that mood in his novel. Almost none of the action of the TV series can be found in the book: no Yakuza, no crown prince, no resistance movement. There are not even any newsreels. Instead, in the book, appropriately, there is a book—a novel within the novel called The Grasshopper Lies Heavy, which narrates an alternate reality in which the Allies won the war. This book is not a clandestine item, however; it is freely distributed, at least within the Pacific states, and many characters end up reading it.

Juliana—who in the novel is not Frank’s girlfriend but his ex-wife—becomes so obsessed with it that she travels to Wyoming to meet its author, Hawthorne Abendsen, who is known as the man in the high castle because he lives in a mountain retreat. (In the TV series, the identity of the titular “man” remains a mystery.)

Every alternate history has a “crux,” a moment when history takes a different path to a new outcome. In The Man in the High Castle, the crux is the attempted assassination of president-elect Franklin Roosevelt, which took place on Feburary 15, 1933. In reality, the assassin, Giuseppe Zangara, missed Roosevelt and instead shot Anton Cermak, the mayor of Chicago, who died a few weeks later. In Dick’s story, Roosevelt is killed, leading Vice President John Nance Garner to take office. Garner fails to pull the US out of the Depression or to arm it for war, and so the country is unable to resist the Axis invaders in the 1940s.

The Grasshopper Lies Heavy, the novel within the novel, imagines this history being righted: Roosevelt survives assassination and the US wins the war. However, the history Abendsen imagines is not “our” history; it is yet another alternate world, in which Roosevelt serves two terms and is succeeded as president by Rexford Tugwell, one of the members of the New Deal’s “brain trust.” It is Tugwell who then wins World War II, since he has the foresight to order the US fleet out of Pearl Harbor before it is attacked—something that Roosevelt, in reality, failed to do.

By placing a book about an alternate reality at the center of his own book about an alternate reality, Dick creates a wilderness-of-mirrors effect. The history Abendsen imagined is no more “correct” than the history Dick himself imagines. But by proliferating the possible courses of events like this, Dick casts a kind of doubt on the history we recognize as true. We live in a world where America did win World War II, and to that extent we see it as having taken the right course. Good triumphed over evil and the world remained livable.

But ours is also a world in which the Holocaust took place and the atom bomb was dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The happy ending of World War II was a forty-four-year cold war in which the world stood constantly at the brink of nuclear annihilation. Perhaps, Dick leads us to wonder, we see true history as good history only because it is the one we are used to. Seen from another perspective, we ourselves inhabit what might be called “bad history”—a reality in which things occurred that ought not, by any standard of sanity and justice, to have taken place.

The fragility of the boundary between good history and bad history—and the impossibility, sometimes, of telling them apart—is the real subject of the best alternate World War II stories. One of the most popular, Fatherland by Robert Harris, is a police procedural set in an alternative history in which Hitler managed to conquer the Soviet Union, though he did not invade the United States. In sketching the geopolitics of this world, Harris suggests that it would not actually be much different from our own: instead of a cold war between the US and the Soviet Union, there is a cold war between the US and a nuclear-armed Nazi Germany. (Indeed, there is even a President Kennedy—except it is not John Kennedy, but his father, the appeaser Joe.)

To the characters in Fatherland, life in a Nazi empire is maddeningly normal, in part because nobody is officially aware of the Holocaust, which remains cloaked in “night and fog” just as it was in the actual Third Reich. The plot of Fatherland involves the hero, a cynical detective named Xavier March, trying to solve a murder that turns out to be linked to the extermination of the Jews. In revealing the culprit, Harris suggests, March will publicize the Holocaust, and somehow the course of history will change for the better.

In the real world, however, the Holocaust was known about almost from the moment it began—and yet it still took place. The form of the detective novel inevitably suggests that solving a mystery will bring justice to the world: the murderer is captured, the crime avenged. But real history is the opposite of a detective novel, in that it exposes the hollowness of such retribution. The Nuremberg Trials recorded Nazi crimes, but they didn’t “solve” them; justice can write history, but not rewrite it.

It is when we recognize this limitation of historical writing that we feel the need for counterhistories. Walter Benjamin expressed something like this in his last work, “Theses on the Philosophy of History.” “To articulate the past historically,” Benjamin writes, “does not mean to recognize it ‘the way it really was.’ …It means to seize hold of a memory as it flashes up at a moment of danger.” Benjamin was writing in 1940, a moment of supreme danger for Europe, and for himself as a German Jew. With Hitler triumphant in France, and with America and Russia not yet in the war, it was easy to recognize the true history of 1940 as “bad history”—as if events had pivoted into an intolerably evil dimension.

That is why, in this “moment of danger,” Benjamin clung to the desperate, metaphysical faith that he had described years earlier in his essay “The Task of the Translator”:

One might…speak of an unforgettable life or moment even if all men had forgotten it. If the nature of such a life or moment required that it be unforgotten, that predicate would imply not a falsehood but merely a claim unfulfilled by men, and probably also a reference to a realm in which it is fulfilled: God’s remembrance.

When history fails to fulfill the just claims of human beings—and when doesn’t it?—it is up to the writer, Benjamin implies, to remember or invent the world that should have been, and in so doing to play a divine role.

This is exactly what Hawthorne Abendsen does in The Man in the High Castle. Indeed, there is a strong suggestion, in the book’s final scene, that Abendsen dwells in our reality, rather than the alternate reality of the rest of the novel. (He may even be a pseudonym for Philip K. Dick.) In that case, when Juliana accosts him, she is a kind of ghost—“a daemon, a little chthonic spirit,” as Abendsen puts it—come from her bad world to demand justice from our good one. This places Abendsen, and Dick, in the position of God, the God we all cry out to from our bad world to demand rectification and redemption. But Abendsen can do nothing for Juliana, just as the writer can do nothing to amend real history. The continuing popularity of World War II counterhistories is a measure of how much we wish—or fear—that things had been different.

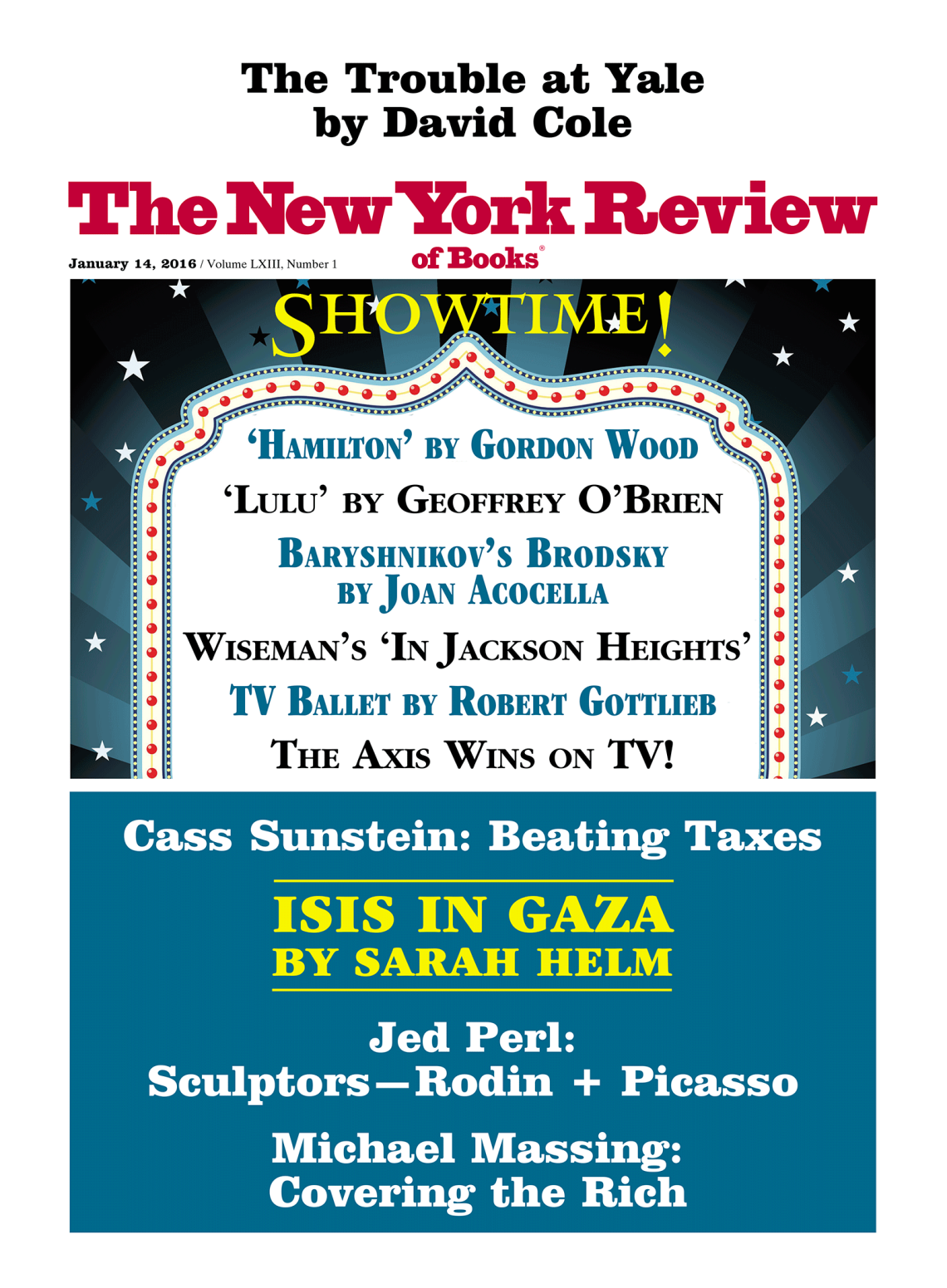

This Issue

January 14, 2016

ISIS in Gaza

How to Cover the One Percent

A Ghost Story