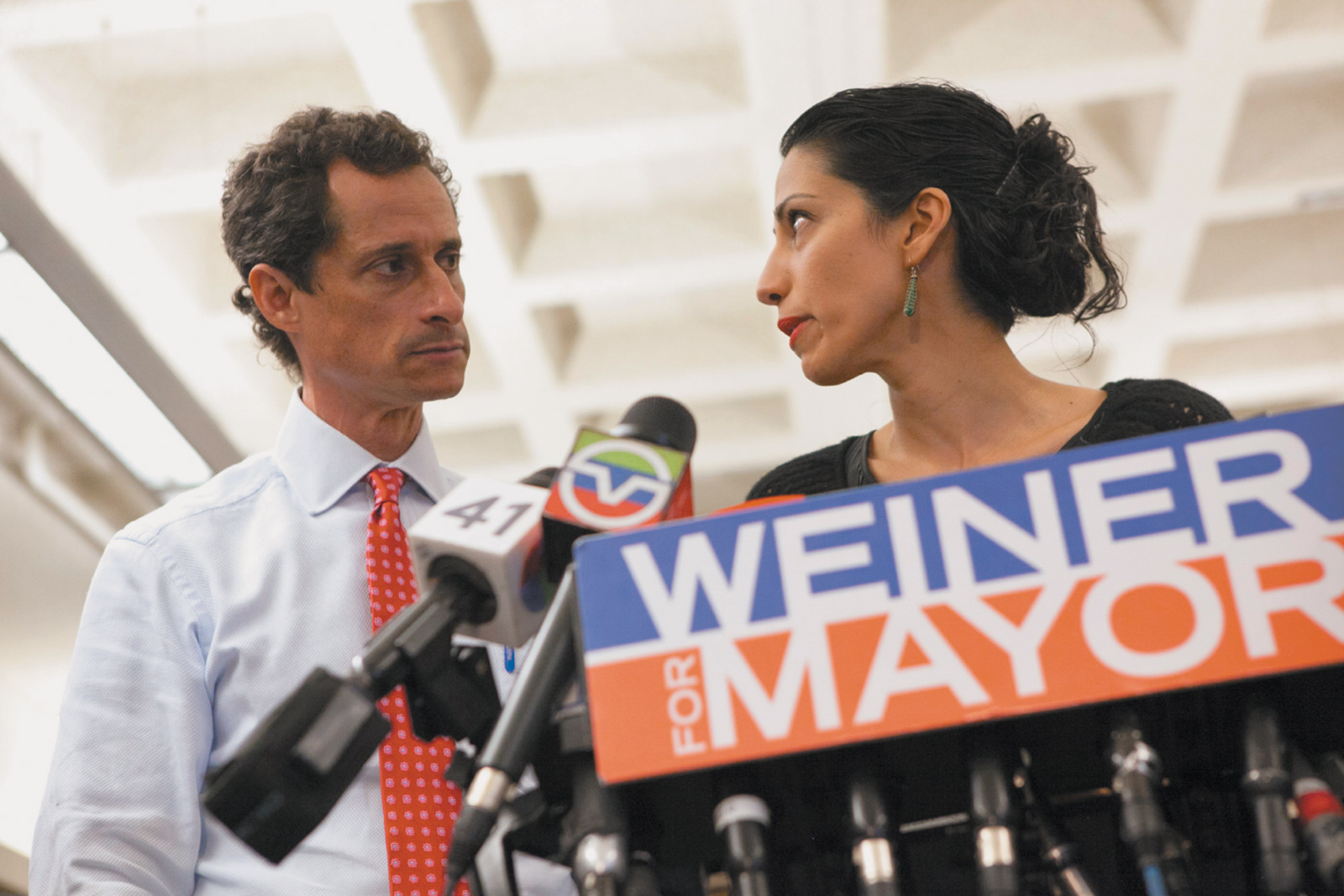

Eric Thayer/Reuters

Anthony Weiner and Huma Abedin at the press conference announcing his intention to stay in New York’s mayoral race despite new revelations about his explicit text messages to women sent after a similar scandal in 2011 that had forced him to resign from Congress, New York City, July 23, 2013

Huma. She is magnificent, a blaze of chic and slender sanity. When Huma Abedin appears on screen in Weiner, the new documentary by Josh Kriegman and Elyse Steinberg about her husband, former congressman, mayoral candidate, and shanda for the goyim Anthony Weiner, her beauty and power and elegance dare the waters to roil around her. The waters take her up on it.

The film picks up the tale of Anthony Weiner after he has already risen, a spirited, take-no-prisoners congressman, and fallen, yet another politician caught in an embarrassing sex scandal. He’s the New York politician whose pictures of his genitalia, shared with several women he never met, ruined his career. Twice.

Weiner is a baffled and sympathetic film, allowing Weiner’s manic charm to lull us into amnesia and Huma’s quiet, almost sleepy poise to wake us up to political and emotional reality. Even when Huma is taut and strained, there is something reassuring about her, something naturally composed. In one scene, when Weiner is on the rise again, running a strong campaign in 2013 for mayor of New York, the camera observes the husband and wife as a new scandal breaks. Behind them, TV screens glare and news shows feature a blown-up cell phone portrait of Anthony naked; then, another photo: the candidate’s crotch, close up, his proudly displayed penis digitally scrambled like a whistleblower’s face. Anthony is fretting, talking, strategizing. Huma paces, arms folded, silent, shaking her head, shaking her head, slowly shaking her head. The look she gives him—it’s eloquent: stunned, superior, dismissive, disbelieving, disgusted, unsurprised. It is a wifely look.

The way I was able to remember the use of the Latin gerundive in high school was the word “pudendum”—that of which one ought to be ashamed. In this time of cultural immodesty, the pudenda are no longer inherently shameful. But getting caught with your pants down is, and Anthony Weiner became a national joke, an international joke, when his distended underpants first made their way from one woman’s cell phone to every corner of the Internet and beyond—newspapers, cable TV news, late-night talk shows, The Daily Show, The Colbert Report.

The film has a number of clips I remember laughing at. But with respect to Anthony Weiner as a human being, they are less funny. The whole subject of the scandal and its lingering questions—Why did he do something so obviously stupid? Why does she stay with him?—seem less funny and more perplexing. The documentary is achingly confusing and true in a way we often associate with fiction. Anthony Weiner would be a memorable fictional character, New York’s own Phineas Finn, flawed, weak, charming, moving, and human; an honest man who does not always tell the truth.

When the first picture—of Weiner in his bulging underpants—surfaced in 2011, sexting was the stuff of hand-wringing editorials not about congressmen but about middle school children, so young and ignorant of the possible consequences of revealing their naked selves to the World Wide Web, showing off, their brains addled by adolescence and an overly sexualized popular culture. This was a phenomenon that parents and teachers worried about. Then came the picture of Anthony Weiner’s weiner, and sexting was off the family health page and onto the political page. No one could look away. No one could resist the pun (I just failed to resist it, and I tried). Everyone loves a good scandal, everyone loves a politician in disgrace, and this one—a colorful, fiery congressman with a funny name and a surprisingly big member—was just too good to be true.

The film begins after the first scandal and ends after the second, following Weiner around the city as he campaigns in the Democratic mayoral primary. He is a candidate obviously superior to the others—smarter, quicker, more alive with ideas and possibility. The scenes early in his campaign are invigorating, the citizens of New York the best supporting actors imaginable. Maybe it’s because I saw the film in LA, but the New Yorkers with their sweaty shoulders and hoarse accents from every borough seemed gallant to me, wading through the trash of hopped-up lurid scandal to listen to a man who clearly would fight for them. “We’re from the Bronx! We don’t care about that personal garbage,” one woman yells with annoyance at a number of pushy reporters. Catching his eye in the subway, several men tap the tabloid newspapers they hold to bring his attention to positive headlines about him.

Advertisement

But interspersed throughout are bits of an interview the filmmakers did with Weiner after the disastrous election was over. Gaunt, dazed, Weiner discusses his own stupidity with an almost agonized intelligence. He is so cognizant of what an ass he’s been that it is almost heroic. He does not blame the press, though he does say ruefully that it doesn’t do “nuance.” There was “a certain phoniness about how outrageous my behavior was,” he says about the press at one point, a rather gentle assessment of the lascivious sanctimony that greeted his photographs, then adds, “It’s not their fault that they played their role.”

He does not blame, say, his parents or the Republicans or the pressures of the job or even his name. He does not explain himself. He blames himself. “I created the problem.” Unlike so many other repentant politicians, there is no self-righteousness in his condemnation of himself. He is oddly modest, not a characteristic you would expect from a man who ran to be mayor of New York or from Carlos Danger (his pseudonym in one of his sexting adventures). He seems to be, like everyone else, bewildered and saddened by his behavior, as if a beloved dog had suddenly bitten him. He seems, in other words, painfully human.

It was this kind of humanity, I think, that so many New Yorkers responded to when Weiner, just two years after being humiliated and disgraced as a congressman, decided to run for mayor. He had done a crazy thing in private through a medium that does not recognize privacy at a time when the culture does not value privacy. He was an exhibitionist on a cell phone screen, he acted like an idiot, who hasn’t, his beautiful wife forgives him, who are we to judge?

Weiner is a film about imperfection in all its human glory. The man who emerges from the film, and the scandals, is no less baffling than before. Why did he do it? How could such an intelligent person do such a silly thing? Why would he endanger his political career, which was obviously central to his life? How could he endanger his marriage? How could he do that to Huma?

The film has no answers. It is revealing in a more interesting and more profound way. We never learn why; but we are reminded that because we don’t understand a person’s motive for what we consider bizarre behavior does not make them less like us. It makes them more like us. Anthony Weiner is a secret everyman. He was seen as a hero, then a fallen hero, then a hero for redeeming himself by acknowledging his weakness and getting back into the ring. He captured the political imagination of New Yorkers with this narrative. But nobody likes a fool, least of all New Yorkers, and Anthony Weiner made a fool of himself.

When I spoke to one of my sons about Anthony Weiner the other day, I said, really, what did he do, exploit himself, no one else. He was not a priest raping children, not a teacher sleeping with a student, not breaking banking rules to hide his outrageous payments to prostitutes, not a ranting homophobe secretly seeking other men through glory holes in a bathroom cubicle, not a priapic millionaire chasing a terrified maid around a hotel room. There are scandals and then there are scandals. Anthony Weiner’s scandal was so very scandalous not because it was heinous or harmful, but precisely because it was so absurd. He was an adult showing off his nethers to another adult show-off.

My son gently reminded me of power structures and hierarchies. I should not ignore Weiner’s position as an older man of power. Sometimes, though, power resides less with the powerful than with the ruthless. It’s true that Weiner was a ruthless congressman, even by the standards of that tribe. Early clips from the film show him banging the podium, pushing the microphone away like a bandy little Roger Daltrey. As a congressman, he could hang on to an issue, including bad issues, like a pit bull fighting in a circle of dirt.

In one scene in the film, Weiner is campaigning in a Jewish deli, with lots of back-patting and congeniality amongst the pastrami and corned beef. As he leaves, one man in a yarmulke makes a remark that sets Weiner off (we later learn it is a comment about Huma) and he’s up in the man’s face like a manager confronting an umpire. “You’re my judge?” he screams. “You’re perfect?” On and on it goes. A bearded Orthodox man in a black hat turns to the camera and asks, mournfully, “Why didn’t he just walk away? Everything was going fine.”

Advertisement

He was a bull-headed and tenacious politician and campaigner, but Weiner, unlike the ruthless politicians, like LBJ for instance, whom Americans have come to know, is not ruthless in his self-regard. He is openly puzzled by himself, which is tremendously refreshing. And he grows weary of himself, almost as weary as New York voters grew to be. At one point the filmmakers show us Weiner in MSNBC’s New York studio, headphones on, facing a camera, as he is interviewed by Lawrence O’Donnell. In a rather prissy but almost cordially prosecutorial tone, O’Donnell says pretty much what we’ve all been thinking—you’re a gifted, successful politician, so what the hell were you thinking? Obviously there must be something wrong with you, clinically wrong with you. Don’t you think something’s wrong with you?

Weiner loses whatever poise he has been hanging on to and whatever strength. He hollers back like a child, he squirms, he whines and jeers. Later as he’s watching the clip on his computer, dark circles under his eyes, laughing almost maniacally, Huma walks by, obviously horrified. Weiner ruefully points at his own crazy, leering image on the screen. “Whatever the opposite of that is,” he says softly, “is what Huma is.”

Then there is Sydney Leathers, Weiner’s twenty-two-year-old sexting partner, one of them, anyway. One who came forward. Way forward. Was she the victim of an older man’s perverse desires? Was she betrayed by her political hero? Was she lured into this behavior and then devastated by the realization that her hero had feet of clay, so devastated that when she saw he had gotten back together with his wife as if everything were normal, she was enraged and had to explain to the world that even after he apologized to the country and resigned from Congress he continued to send dirty pictures of himself to twenty-two-year-old admirers? Possibly. That’s certainly what Sydney Leathers says. On The Howard Stern Show. The media outlet known for its sympathy to abused women.

If Anthony Weiner is the perfect Trollopian political hero, Sydney Leathers is almost too broad a character for a novel. She is engorged with her own sudden importance, her pumped-up outrage, her smirking flirtatious poses for whoever might glance her way. With her newly augmented breasts bursting out of her red dress, she giggles and stalks the miserable Weiner on election night as he scurries through the back hallways of a McDonalds, dragging his simmering wife with him. I’m happy that my sons are such good feminists that they recognize structural oppression. But sometimes a foolish simpering twenty-two-year-old must be taken as seriously as a foolish middle-aged congressman. And taken seriously, Sydney Leathers is not just silly, she is nasty. If Weiner is deep but unconscious, she is shallow and unconscious. Huma’s dignity resides in her inscrutable strength, Weiner’s in his inscrutable weakness. Sydney Leathers, smirking and appropriating the grief of real victims, has no dignity at all, and that is one of the most distressing things about the film, one we cannot blame Anthony Weiner for.

We might accuse that other villain of the piece, social media, I suppose. It is startling to notice over the course of the film how much Weiner is on his phone. It is an addiction, as we have read in articles right next to the articles on sexting. At one point, Weiner half-heartedly tries to explain sexting as being like a video game, something unreal. So if we, like O’Donnell, insist on a diagnosis, that is probably a fruitful place to look. But without social media, we would not have the end of this film, which is sheer joy and pure art.

Anthony Weiner is posing for a photograph, an innocent, fully clothed photograph taken by a passerby on his cell phone. As he smiles and holds his pose, we get the irony and think we’re done with the shot. Then a little boy, maybe nine years old, walks up, on his way home from school. He stops. His mouth opens. He does an exaggerated double take, then another, backing up in his excitement and awe. He pulls out his own cell phone.

“Mom! Mom? Mom!” cries the boy into his phone as he trembles, dancing with excitement. “You won’t believe it! You won’t believe who I see.”