One of my favorite novels is by Compton Mackenzie, a Scottish writer known today, if he is known at all, for his whimsically comic Whisky Galore (1947) and his ambitious early novel Sinister Street (1913). The one I love, however, is Extraordinary Women: Theme and Variations (1928), a satirical roman à clef about the sapphic adventures of the unorthodox and eccentric inhabitants of an island modeled after Capri during World War I. After Sappho, a novel by Selby Wynn Schwartz that was longlisted for the Booker Prize in 2022, is many things, none of them satirical, but I kept thinking of the title of Mackenzie’s book as I read it.

The basic story of After Sappho is both simple and engaging: in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, a number of talented, daring women, all inspired by the Greek poet, create some of the period’s most important artworks. The many colorful, troubled, and valiant characters break from the bonds of oppressive tradition and find themselves, and one another, in an inspired era of secretive but glorious freedom that does not last.

Colette and Gertrude Stein and Natalie Barney and a few other sapphic household names appear; for those familiar with the great lesbian flowering of this time, many of the other characters and their tales will also be familiar. There are, however, a number of historical women who may not be familiar at all. Schwartz begins the novel in 1885 with a fragment announcing the birth of the poet and playwright Lina Poletti—who was “born into a line of sisters who didn’t understand her”—and ends it in 1928 with Virginia Woolf, that sister who understood so much. Schwartz precedes most vignettes with a specific date, so that they appear as tiny episodes in time, though they don’t necessarily follow chronological order.

After Sappho is a story woven from many stories. Biography, fragments of poetry, legal history, feminist history, theater criticism, art criticism, architecture criticism, literary criticism, Greek grammar, gynecological discussion, and both well-known and obscure sapphist lore all loop their way through this intricately fashioned book. Schwartz is knowledgeable and she is certainly polemical, but After Sappho reads gently, insistently, a quiet explosion of struggles and triumphs, of absurd conventions and absurd rebellions against them, wafting delicately down through decades. Narrated in the first-person plural, After Sappho is like a choral memoir, the chorus assembled temporally as well as spatially.

“This is a work of fiction,” Schwartz states in an afterword. But she immediately questions that characterization:

Or possibly it is such a hybrid of imaginaries and intimate non-fictions, of speculative biographies and “suggestions for short pieces” (as Virginia Woolf called them while she was drafting Orlando), as to have no recourse to a category at all.

Perhaps the self-conscious postmodern world of academia of these past few decades immediately comes to mind, and perhaps we recoil. Yet however the author chooses to exalt her work for its complicated structure, or perhaps to protect it from readers expecting a traditional novel, After Sappho is indeed a novel, a sympathetic tale of the struggle of women during the Belle Époque and the beginning of modernism. The ingenious way it is told, its seemingly disconnected patches gliding through time and space like scraps of clouds in the sky, provides its own narrative momentum.

“A poet is always living in kletic time, whatever her century,” Schwartz writes, referring to a poem addressed to a deity. “She is calling out, she is waiting. She lies down in the shade of the future and drowses among its roots.” Although the poet is lying beneath the future, time here is also the shade of the past, and the grammatical case she uses is the “genitive of remembering”:

The genitive is a case of relations between nouns. Often the genitive is defined as possession, as if the only way one noun could be with another were to own it, greedily. But in fact there is also the genitive of remembering, where one noun is always thinking of another, refusing to forget her.

While the subject of a sentence takes the accusative case when a straightforward act of memory is involved (as in “I remember her”), the genitive is used instead when, as one old Latin grammar explains, what is meant is “to be mindful or regardful of a person or thing, to think of somebody or something (often with special interest or warmth of feeling).” For Schwartz, and for these extraordinary women, what is warmly remembered is Sappho.

Plato called Sappho the Tenth Muse, and just her name carries an aura of lyric eroticism. Catullus adapted her poetry into Latin. The word “bittersweet” seems to have originated with her—a dazzling legacy of its own. She is also said to have introduced a type of lyric stanza; discovered a musical scale, the Mixolydian mode; and invented a lyre that is named after her, not to mention the plectrum, a pick for plucking a lyre. She has fascinated and mystified scholars: Did she run a school for aristocratic girls preparing them for marriage? Or was it a school for prostitutes? Or was it a school at all? These debates have spilled over from one century to the next. What no one denies, however, is that Sappho introduced into poetry an intimacy that did not exist before her but has survived her for more than two and a half millennia. As has her identification—and that of Lesbos, the island she lived on—with romantic love between women.

Advertisement

What has suffered a more tattered afterlife are Sappho’s actual poems. Of the nine volumes that are reported to have existed in the Library of Alexandria, only two complete poems and about two hundred fragments have survived, some of them discovered in the not too distant past on the papyrus wrappings of Egyptian mummies. Yet these scraps of poetry have for centuries inspired artists, poets, playwrights, novelists, and composers. To that legacy Schwartz adds women in general and lesbians in particular, for whom Sappho has long been a light against the darkness of prejudice.

Schwartz, whose own prose can be both tender and passionate, quotes fragments of Sappho’s fragments (the translation she uses is If Not, Winter by the poet and scholar Anne Carson, an obvious and gratefully acknowledged influence):

For someone will remember us/I say/even in another time, Sappho wrote. She was writing of the woman who would lie back with her in the cress and moss at the river’s edge, how darkness would gather in her lap as evening came over them, the melting from that darkness.

Schwartz also writes tenderly and passionately about Sappho’s single words, words that are hard to render in English yet impossible to misunderstand:

One of the epithets of Sappho that is difficult to translate, even for a poet, is this darkly bright hollow of the body. It might be a fold of cloth or flesh, the shadow between breasts, or the surprise of twilight. It might be a sharp, haunted longing that surges in the viscera, or it might be your lap heaped with violets. Whatever it is, Sappho writes, it lasts all night long.

The last half of the nineteenth century and the decades surrounding World War I brought the blossoming of notable lesbians, many of whom populate Schwartz’s book. They came from the United States, like Barney, Stein, Djuna Barnes, and Romaine Brooks; or England, like Woolf and Renée Vivien; or Ukraine, like Anna Kuliscioff; or France, like Sarah Bernhardt and Colette; or Italy, like Eleonora Duse and Poletti and Sibilla Aleramo. Yet it was a tight-knit group, as incestuous and claustrophobic as a small liberal arts college. They inspired one another, slept with and rejected one another, moved on from one to another. Many of them changed their names, some left marriages behind, some left to be married, but they were all drawn at one time or another to Barney’s famous salon at 20 rue Jacob in Paris, where she held gatherings of women in Greek dress dancing in her garden beneath the Doric columns of a small neoclassical temple. (The cult of ancient Greece was everywhere. After a summer spent with Isadora Duncan, Mary Desti, the mother of Preston Sturges, sent six-year-old Preston to school in Chicago wearing sandals and a little Grecian dress.)

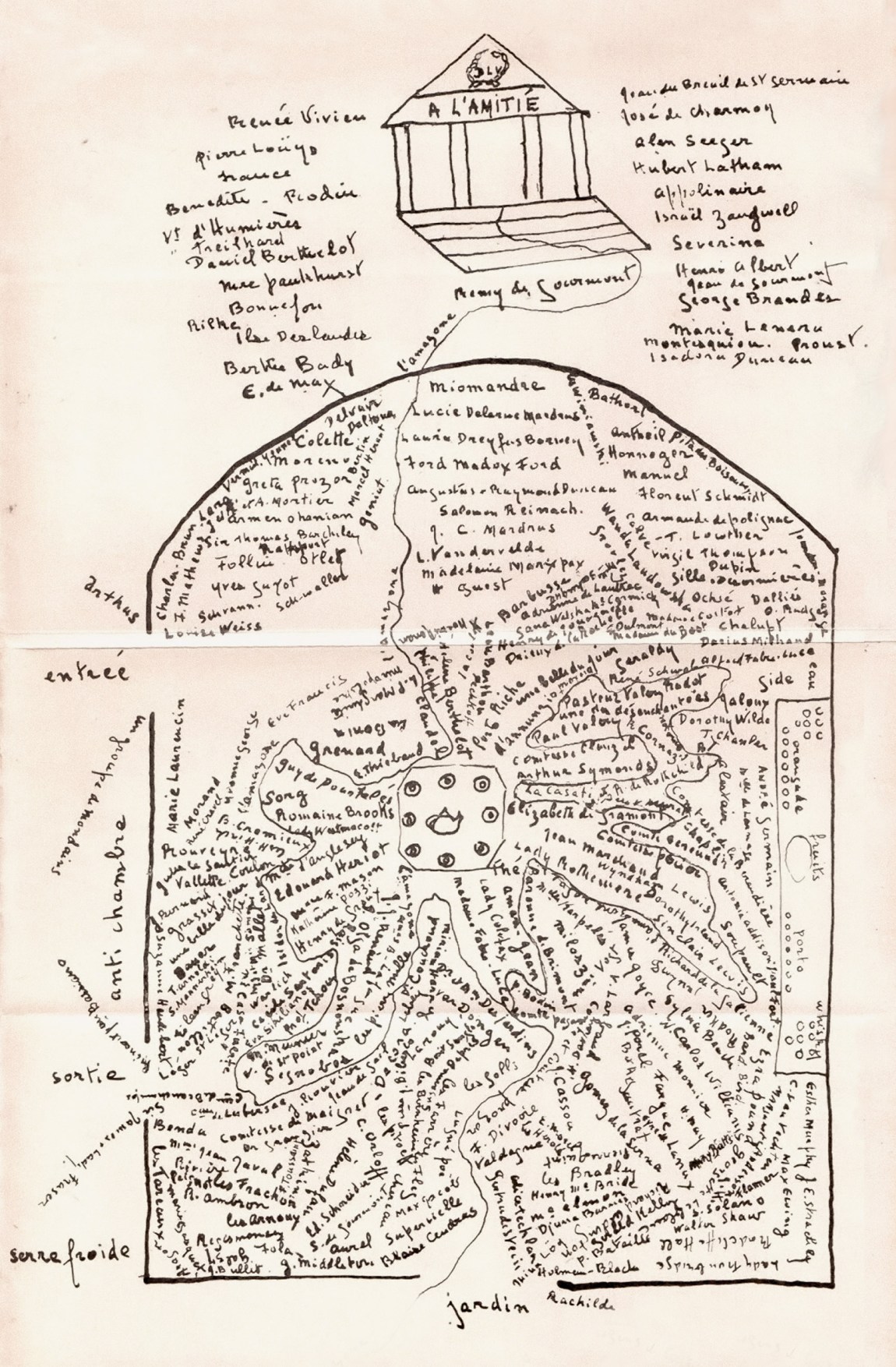

Barney, an artist and unabashed and astonishingly successful seductress of women, was born in Ohio and moved to Paris after she inherited a fortune at twenty-one. Her literary and artistic salon was frequented by so many socialites, aristocrats, dancers, artists, and writers that she once drew a map of friendships, a lacy, spidery web of names crowded together in a plan of her garden, the temple at the top of the page (see illustration on page 12). After Sappho, with its labyrinthine yet clear structure, shares some of the friendship map’s qualities. There are around fifty women mentioned: a maze of formidable ladies. But the rhythm of the book, its rippling movement among decades and epochs, is almost hypnotic. The relationship between Sappho’s words and the lives of the modern characters becomes seamless, vibrant, and important.

“The first thing we did was change our names,” Schwartz writes in the first sentence. “We were going to be Sappho.” Inside Barney’s temple was a bust of the poet. Around it and her descendant the world of artistic Paris gathered and reveled in their private freedom, discovering one another and the lineage they had not known they shared:

Advertisement

Without Natalie, Liane might never have known she was one of us. Without Eva Palmer, Natalie might never have read Sappho. Without Sappho, Pauline Tarn might have mildewed in London darning the heels of sensible stockings….

We gathered around Natalie and gleaned what we needed. She had made a haven from fragments.

One of those who changed her name was the Italian feminist writer Sibilla Aleramo, who was born in 1876 as Rina Faccio. “A new name was like a blank notebook,” Schwartz says. “Rina could write herself into it. With a folio of fresh pages she could write herself into becoming Sibilla, enigmatic and sibilant.” In 1906 she published the autobiographical novel Una donna, forgotten now but groundbreaking in its time. An account of her miserable marriage and the Italian culture that made it so difficult for her to escape, the book was translated into English with the title A Woman at Bay.

Aleramo’s early life is marked by tragedy so darkly dramatic it verges on operatic. Schwartz writes:

In 1889 Rina’s mother told her something wordlessly that she never forgot. Her mother was standing at the window, looking out, in a white dress that hung off her shoulders. Then suddenly her mother went out of the window. She plummeted, her dress trailing like a scrap of paper. Her body landed two floors down, bent into a bad shape. That was what Rina Faccio’s mother had to say to her.

The mother’s message does not do Aleramo any good. A few years later, with her mother in a lunatic asylum, Aleramo was raped in her father’s glass bottle factory. Her rapist’s hands, Schwartz writes, were “brute hands that fastened on levers” in his work. Article 544 of the Italian Penal Code, which “was like an iron lever,” Schwartz notes, allowed Aleramo’s father to force her to marry her rapist, to be “handed from one household to another, sallow and dazed.”

Schwartz makes the leap from this personal tragedy to the struggles of the recently united Italy by means of the simple repetition of “lever,” taking us back to 1865 and the Pisanelli Code, hailed as “a triumph of the unification.” Almost simultaneously, she also escorts us back to the materiality of paper, of writing, of messages handed on just as Sappho handed on her poetry:

Under the Pisanelli Code, Italian women gained two memorable rights: we could make wills to distribute our property after our own deaths, and our daughters could inherit things from us. Our writing before death had never seemed so important….

Our words, which had always before been seen as gauzy and frivolous, gained a new weight as they settled on the page.

One of Schwartz’s most impressive gifts is her ability to spin a term around and around until it releases all its meanings, its powers past and present, its glory and its stink. Explaining the idea of patria potestas, she writes:

Patria meant both “the father” and “the fatherland,” and potestas was the thick knot of their power to dispose magisterially of women, children, and domestic goods. Patria potestas had been handed down from father to father since the Roman Empire.

She then explains that the essence of the Italian Penal Code’s Article 544 (which was not repealed until 1981) is encompassed in the verb impadronirsi,

which binds together so many forms of power that it is difficult to translate. Impadronirsi means to become the patron and possessor, the proprietor and the patriarch; to conquer, to overmaster, to take charge, to gain ownership; to act with the impunity of a father who, according to Article 544, may expunge the crime of the rape of his daughter by marrying her off to the man who has raped her, without a dowry. This is called a “marriage of reparation,” because it satisfies both men involved.

Here words hold power, not just meaning. Leaving words behind is as revolutionary an act as embracing the words of Sappho or echoing Virginia Woolf: “Always, however we left the verb impadronirsi, we went with no return: thus we embarked, each in her own way, on the voyage out.” The voyage out is more than metaphorical for the extraordinary women Schwartz writes about, more than an escape from repressive marriages and customs and laws. It is a voyage forward into love, into creative works, and into a new world.

Each instance of Schwartz zeroing in on a specific law or a Greek or Italian word provides a contrast to her winding, breathless, intimate narrative, and that contrast is just sharp enough to force the reader back a step. The irrationality of what was once considered unassailably rational comes into clear, keen focus. The absurdity and fallacy of conventional opinion dart among the tales of women struggling to find a place for themselves in the world. Quotations from medical papers and contemporary newspapers create a similar effect, though such fragments in a novel that jumps between real historical people can also narrow the scope to the point of obscuring some intriguing bits of scenery. Schwartz does not view this as a compromise. She is, for example, unambiguous in her decision to skip past the men in the lives of her characters: “Men like Gabriele d’Annunzio—who swaggers prepotently through every account ever written of Eleonora Duse and Romaine Brooks—do not merit here even a footnote about who they married or how they died.”

When Schwartz mentions Noel Pemberton Billing, a reactionary English oddball conspiracy theorist who set fire to his headmaster’s office as a teenager, ran away to South Africa, became a boxer, designed a clumsy four-winged airplane to fight zeppelins, opened an aerodrome, became a member of Parliament, and founded a newspaper primarily to attack Germans, Jews, and homosexuals, she whittles this odious man down to a libel case against him—though what a libel case:

Oscar Wilde had been dead eighteen years when the dancer Maud Allan became Salomé. She was giving private performances in London, we had heard, when Noel Pemberton Billing got wind of it. Scenting lesbian ecstasy, he became hysterically excited; immediately he denounced her in the papers as a high priestess of the Cult of the Clitoris.

Coming from Billing, this meant she was not only a lesbian but also a secret agent for the kaiser. Allan, a world-famous dancer, sued Billing for libel. It was, not surprisingly, a sensational trial: “A certain Lord was overheard remarking to a fellow at his club, I’ve never heard of this Greek chap Clitoris they are all talking of nowadays!”

Schwartz’s characterization of Billing is brief and harsh, as it must be in this narrative. After Sappho is not a history of conspiracy theories or early aircraft. It is not a full biography of Duse or Brooks or any of the other characters. It is, rather, a novel not only in but about the first-person plural, about a character made up of all the remarkable women after Sappho. But it is worth noting that one of the many pleasures of After Sappho, perhaps not anticipated by the author, is hunting down the stories behind the stories she chooses to tell: the transcript of the Billing libel trial, for instance, during which Allan was browbeaten into admitting that she knew what a clitoris was and, in McCarthyite fashion, Billing claimed to be in possession of a black book full of the names of homosexuals, all of whom he was sure were traitors in league with the Germans. It may take you twice as long to read the book, but I found the opportunities for googling and buying out-of-print books by out-of-favor or forgotten writers from the days of courtesans and amateur lady archaeologists irresistible.

Schwartz’s women drove ambulances during the war, translated Greek, started libraries, fought for women’s suffrage, recreated Delphic festivals, built houses of blue glass, wrote new kinds of novels, and painted new kinds of portraits. They were sensuous and lively like Colette. They wanted traditional marriages like Brooks. They danced in filmy garments around a backyard temple and scandalized the neighbors because their dancing, their robes, and their lives were scandals. They also suffered terribly, and their suffering was both grimly private and out in the public square. While in Naples, Duse, twenty-one and unmarried, became pregnant. Children were called e’ criature in Neapolitan, Schwartz writes:

The saint of criature denied by their fathers was SS. Annunziata, for whom the foundling house was named. In the wall of the foundling house a wheel was fixed; it turned only one way. An illegitimate child placed on the wheel was thus turned irrevocably into an orphan.

If that sounds like something that is happening in the United States today, it is not the only contemporary echo of what women suffered more than a hundred years ago. When Sibilla Aleramo went to see Ibsen’s A Doll’s House in 1901, her eyes filled with tears. Schwartz writes, “Nora was clicking the door shut on a century of women whose only verb had been to marry.” Aleramo’s reaction to the play “was not crying, exactly. It was the century leaving the body.”

We are well into a new century, and the hopes of these courageous, eccentric, gifted women are still being challenged. Kletic time, it turns out, is with us still.

This Issue

October 19, 2023

Heading Toward a Second Nakba

Conspicuous Destruction