In February 1897 a New York City lawyer named Bradley Martin and his wife, Cornelia, decided to host a costume ball at the Waldorf Hotel. New York had been staggering economically since a national depression began in 1893, and the Martins conceived of their soiree as a form of trickle-down economics: they would spend lavishly on food and labor, promise to hire local musicians, and issue invitations not long before the event, so women would have to order costumes from New York dressmakers rather than from Paris.

Rarely has a social event nominally for a good cause seemed more tone deaf. When their seven hundred–plus visitors from across the country arrived, they were greeted by a simulacrum of royalty: Bradley in a powdered wig, posing as Louis XV; Cornelia wearing a ruby necklace that had once belonged to Marie Antoinette; the hall refitted to look like a replica of Versailles. Fearing that radicals might attack the ball, two hundred uniformed policemen and forty undercover detectives patrolled the streets outside. When the party (which cost $9 million in today’s dollars) was over, the New York City government—as though taking seriously the Martins’ claim to want to help the city’s poor—doubled the tax assessment on their West 20th Street house. The couple paid it for one year and then decamped for Europe.

Stephen Schwarzman showed no such nod to the good of the city when he planned his sixtieth birthday bash in 2007. Schwarzman is a private equity mogul whose name adorns the main building of the New York Public Library at 42nd Street. He has often seemed acutely attuned to his own relationship to the Gilded Age, going so far as to purchase a triplex apartment once owned by the Rockefeller family. Hundreds of guests attended his birthday fete at the Park Avenue Armory, a structure built in the late nineteenth century for a national guard regiment assigned to protect the mansions of upper Manhattan from the envious hordes it was feared might come marauding from tenements farther east. Donald Trump attended, Rod Stewart performed, and the party attracted so much hostility from the public and the press (it featured prominently in a 2008 New Yorker profile) that it made Schwarzman and his asset-management company, Blackstone, the face of the excesses of private equity.

It is easy to draw parallels between the Gilded Age of the late nineteenth century and our contemporary era of inequality, but aside from a penchant for conspicuous consumption, there are important differences between the old-time captains of industry and tycoons like Schwarzman. After all, the Carnegies and Rockefellers made steel and pumped oil; the Morgans (and attorneys like Bradley Martin) financed their endeavors, the building of factories and the laying of railroads. Their wealth was created in a mad rush for the profits to be gained by developing an agricultural country into an industrial urban one. But what does Blackstone do? How does it affect our world, and how has it made its owners so phenomenally wealthy?

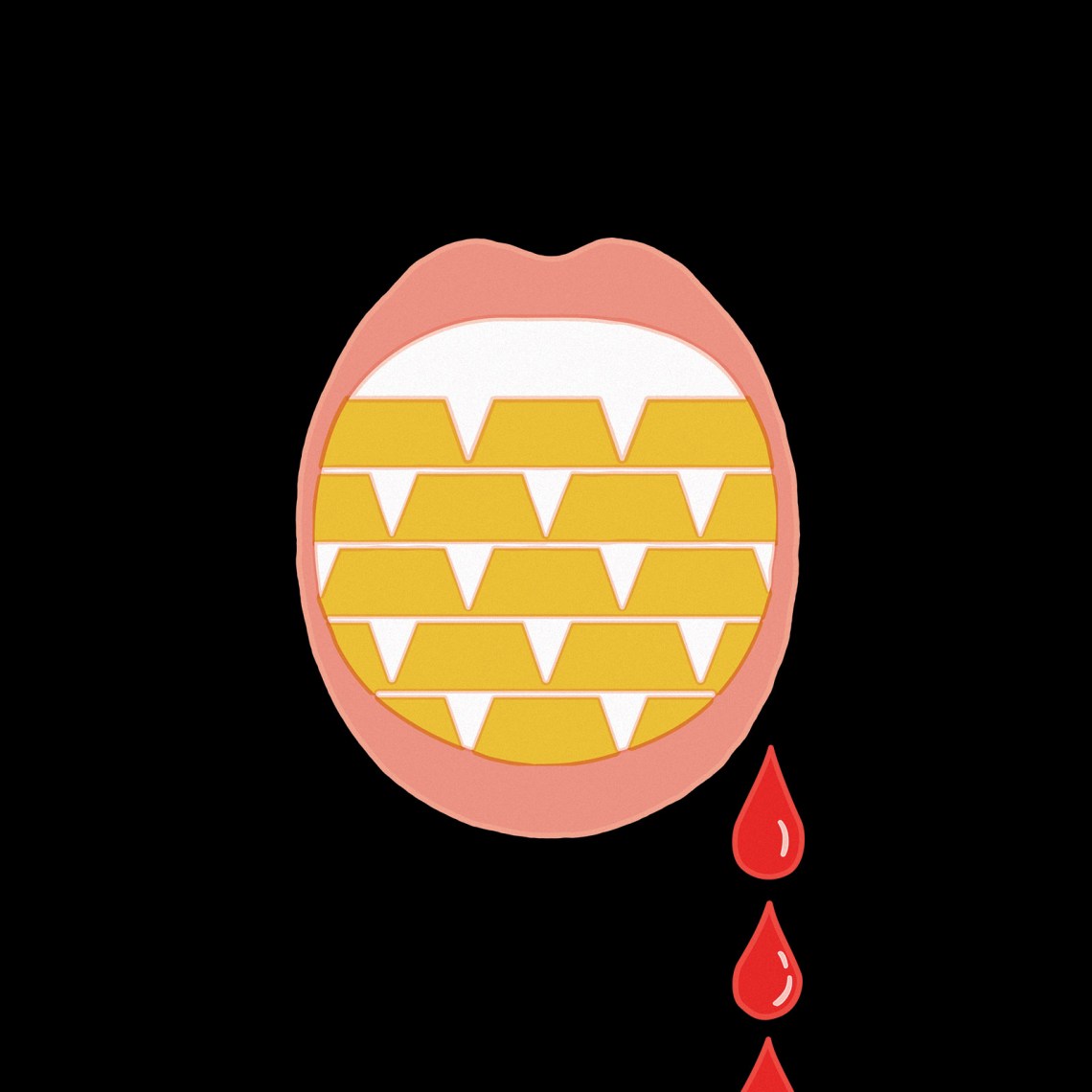

Two new books on private equity—Plunder by the federal prosecutor Brendan Ballou and These Are the Plunderers by the journalist Gretchen Morgenson and the researcher Joshua Rosner—aim to shed light on these questions. Ballou adopts a lawyerly, academic tone, while Morgenson and Rosner prefer cliff-hangers reminiscent of a true-crime podcast; both present forceful briefs for regulating the industry. In the take-no-prisoners style of the Progressive Era’s muckraking reporters, each book provides an impassioned rebuke of the men (they’re mostly men) and women who have profited from private equity.

As their titles suggest, these books revolve around the scandal of looting, in one case explicitly likening private equity executives to pirates from times of yore. Taken together, they raise the question: What if private equity is not a perversion of capitalism (as the authors maintain), but merely a distillation of its contemporary values and practices? What if its leading financiers are an advance guard for our economic elite as a whole? Along with many other popular accounts of private equity, hedge funds, and high finance, the books imply that private equity primarily works by distorting and twisting economic norms. By looking closely, though, we also find the possibility of understanding the problems of today’s economic order.

At the most basic level, a private equity fund is a type of exclusive investment fund—a pool of money managed by professionals to maximize returns for rich investors. Because private equity funds are subject to little regulation by the Securities and Exchange Commission,* investors must be accredited and provide proof of family wealth, and funds often have minimum investment requirements of $10 million or more, although some go as low as $250,000. Mutual funds or hedge funds make money by investing in the shares of publicly traded firms. Private equity funds buy up all the shares of publicly traded companies, gaining complete managerial control. (Sometimes they will acquire companies that are privately held, such as independent medical practices that are limited-liability partnerships.) Usually a purchase is financed with heavy borrowing, so that a newly acquired company is saddled with debt that it needs to repay quickly—often by selling assets or laying off workers.

Advertisement

Eventually, the private equity firm sells the company’s stock on the open market, in the hope of making profits that can be many times the initial investment. Such funds thereby promise exceptionally higher returns than typical stock funds—although as the economist Eileen Appelbaum and the management professor Rosemary Batt argued in their 2014 book Private Equity at Work: When Wall Street Manages Main Street, it’s unclear whether they deliver those results. (Subsequent studies have not been more definitive.)

Private equity is an answer to the “principal-agent problem” that bedevils publicly traded corporations, in which hundreds or thousands of dispersed shareholders are the legal owners of a business and have first claim on its profits but do not actually make any of the day-to-day decisions about how it is run. Private equity firms collapse this distinction by making the investors into the managers, only they don’t do this for just a single company, as in the case of privately owned family firms—Koch Industries, say, or Ford Motor Company in the era of Henry Ford—but for many different companies. Distant investors who have little knowledge of day-to-day operations are given full managerial control of the CEO. One may imagine the private owner of a firm as a patriarch taking an intense personal interest in his domain, while for private equity moguls, the actual people, assets, and products that make up a business are just part of the “portfolio”; they dissolve into abstract statements of profit and loss.

Many see private equity as a way to shake up stodgy companies and revolutionize sleepy industries with a healthy dose of profit motive and to raise money for productive, innovative endeavors. Making the investors into the managers and loading on debt to create a sink-or-swim urgency is supposed to goad competitiveness, rousing companies to jettison their routines so they can deliver better, cheaper products and services—Joseph Schumpeter’s “creative destruction” at work. This faith in private equity is widely held across the political spectrum. In 2012 Bill Clinton went on Piers Morgan Live (where he was interviewed by Harvey Weinstein) to defend Bain Capital, the former employer of Mitt Romney, against Democratic attacks during Barack Obama’s reelection campaign. Clinton insisted that Romney had had a “sterling business career” at the private equity firm: “I don’t think that we ought to get into the position where we say this is bad work.”

But is this view based in reality? Morgenson, Rosner, and Ballou say no. Private equity, they suggest, is not just an “extreme version of capitalism,” as Ballou puts it, but something ominous and new—a “much darker” enterprise bringing business and government together to exploit “legal gaps and obscure government programs” for enormous short-term profits. The result is an entirely perverse economic order in which the imperative of getting rich quickly has preempted every other goal.

The idea that shareholders and debt could be used to galvanize sluggish companies goes back to the economic slowdown of the 1970s. In the postwar years the modern corporation, with its division between ownership and control, had come to seem the embodiment of technocratic power, a model of rationality and efficiency. But as American economic might wavered under challenges overseas and unrest at home, the very same institutions instead began to exemplify bloat.

The causes of American economic decline were many—greater competition from manufacturers in Europe and Japan, rampant inflation, energy crises, the Vietnam War’s drain on economic resources, and the relentless pressure to speed up production and the reaction against it in wildcat strikes. But economists, law professors, and Wall Streeters focused on something else: corporate structure. The more serious problem, they proposed, was the rise of conglomerates—large, unwieldy companies created by mergers in the 1960s—which CEOs (who often had scant connection to the companies they were supposed to manage) had little desire to change in ambitious ways. The solution was to empower an activist cadre of profit-hungry shareholders who would storm the corner office and shake up indolent managers. Their watchwords were disruption, not stability; individual greed, not corporate responsibility; the power of the market rather than that of the CEO.

The result was the leveraged buyout wave of the late 1970s and 1980s. One of the earliest LBOs was led by William Simon, a financier who had served as Treasury secretary under Gerald Ford (whom he had urged to withhold federal aid from New York City when it faced bankruptcy in 1975). Author of the antiliberal A Time for Truth who also served as president of the conservative John M. Olin Foundation, Simon was attuned to the politics of finance and believed businessmen should become far more aggressive politically and ideologically. In 1982 he led a takeover of Gibson Greetings (a greeting-card company) for $80 million. The investors ponied up $1 million; Simon and his partners borrowed much of the difference. Not two years later, Gibson Greetings was sold for $290 million.

Advertisement

The deal made others sit up and take notice, and over the rest of the decade there were thousands of LBOs, often financed by “junk bonds”—risky debt that fetched a high interest rate, creating tremendous pressure to realize savings fast. Because the new owners had little interest in the communities where these firms were located, they had no compunction about firing workers and selling off plants and equipment. They repaid the debts but left a trail of destruction.

The chaos was part of the point. The financiers who sought out LBOs in the 1980s insisted they had the right to flout previous corporate norms and niceties. “Greed is all right, by the way,” the financier Ivan Boesky famously said to business graduates at the University of California at Berkeley, not long before he pleaded guilty to crimes associated with insider trading—a phrase that became the basis for Gordon Gekko’s speech in the movie Wall Street: “Greed, for lack of a better word, is good.” Transgression was the order of the day; strippers and coke went together with the notion that selfishness was a virtue (as Ayn Rand had argued in 1964).

The LBO wave didn’t end well. Hundreds of small banks that had invested heavily in junk bonds (the savings and loan associations) went bankrupt by the end of the decade and had to be bailed out for billions of dollars, while some of the highest-profile traders (Michael Milken, Boesky) went to jail.

After the collapse, few firms wanted to be associated with LBOs any longer, and the buoyant stock market of the 1990s offered plenty of other lucrative options. Private equity emerged as an alternative kind of investment fund in the early 2000s. It gained pace after 2008, when regulations increased for investment banks but not for private equity.

Although the model of private equity is quite similar to that of the LBO, it has become far more central to our economy than LBOs ever were. Today, more businesses are owned by private equity firms than are listed on the New York Stock Exchange. Companies owned by three of the largest firms—Kohlberg Kravis Roberts, the Carlyle Group, and Blackstone—employ more than two million people all together, and companies owned by all private equity firms employ more than 11 million. (The number of employees increased by one third between 2018 and 2022, according to the Private Equity Stakeholder Project, a research group focused on the industry.) They sprawl across retail giants such as Dunkin’ Donuts and Safeway (and the now bankrupt Toys “R” Us and Kmart) to service-sector stalwarts such as hospitals, nursing homes, medical billing centers, day care centers, for-profit universities, and medical, dental, and veterinary practices. Housing, life insurance, water, gas, phone service for prisoners—companies in all these industries are controlled by private equity. Newspaper chains, too, have since the early 2000s become a target for private equity; the largest in the country, Gannett, is now owned by a private equity firm.

Private equity is no longer perceived as a shady realm of fast dealers or a niche of high finance, as LBOs were in the 1980s. CalPERS (the pension for public workers in California) invests heavily in private equity funds, as do other pension funds for both public- and private-sector workers. Harvard and Yale have between 35 and 40 percent of their endowments invested in private equity funds, and on average universities or colleges with more than $1 billion to invest put about 18 percent into private equity. For pension funds of public employees, the promise of high returns seemed like a way to avoid the political problem of raising taxes to make good on their commitments; for universities, endowment-generated wealth might provide a respite from the exigencies of fundraising. Embraced by the most mainstream of institutions, private equity today accounts for at least $7.5 trillion in assets, making up a significant part of our economy.

What does this kind of capitalism look like? As these books present it, private equity firms create nothing and provide no meaningful services—on the contrary, they actively undermine functional companies. Far from creating jobs, companies owned by private equity see the number of people they employ shrink by an average of more than 4 percent within the first two years after purchase—if they survive at all. According to a 2019 study cited by Ballou, one in five large companies taken private in a debt-financed deal declares bankruptcy within a decade.

The authors describe private equity funds running the companies they purchase into the ground. A common maneuver, for instance, is to mandate that a newly acquired hospital or factory sell off its buildings and land—even if the business has no reason to do so other than to pay back the debt the fund incurred to purchase it. In the long term, this means the company is left to pay rent on the same properties it once owned. Often it’s stuck paying property taxes, insurance, and upkeep despite no longer owning the property.

Other tactics include forcing acquired companies to pay “dividend recapitalizations,” in which they borrow to pay dividends to new owners, or myriad advisory and management fees. (As Batt and Appelbaum noted, this is highly unusual: the CEO of a publicly traded firm is not permitted to charge the divisions of that company for his or her guidance and insight.) The acquired companies find themselves weighed down by costs they had never borne before.

When the Carlyle Group purchased ManorCare, the second-largest nursing home chain in the United States, for example, the first thing it did was require ManorCare to sell its real estate. This allowed Carlyle to recoup the money it had borrowed to finance the deal, but forced the chain to pay nearly $500 million in rent annually to keep using its buildings. It was also saddled with $61 million in “transaction fees,” followed by an additional $27 million over nine years in advisory fees. To cover these new costs, ManorCare faced intense pressure to scrimp on patient care, laying off hundreds of workers. Its health code violations rose by more than 25 percent between 2013 and 2017. At the same time, it forced patients to undergo pointless therapies that Medicare would cover, sometimes with absurd consequences—as in the case of an eighty-four-year-old man who was brought to group therapy even after he became verbally unresponsive and his doctor had authorized end-of-life care. Nonetheless, ManorCare declared bankruptcy in 2018.

Private equity seeks out low-wage industries (food service, retail, health care, and security are its largest sectors) in which the consumers are unlikely to complain and in which it can economize brutally without fear of lawsuits. Many of the companies purchased by private equity funds are those that cater to the poor, sick, and vulnerable: payday loan companies, ambulance companies, hospitals, nursing homes, hospices. A slew of prison services (food, collect phone calls, health care, ankle monitors, even debit cards given to prisoners upon release) are provided by companies owned by private equity firms.

Health care, which saw $90 billion of private equity deals in 2021, may be especially appealing because it is heavily financed by the government through Medicaid and Medicare as well as the private insurance industry. In addition, its customer base is steady and reliable: patients are loath to change doctors, and private equity firms often “roll up” several adjacent practices so they can’t compete against one another and can charge higher prices. But medical professionals are wary of these takeovers. They have claimed to witness cutbacks on all manner of supplies—leaving them with cheap needles that break when nurses draw blood or shortages of gauze, antiseptic, and even toilet paper. Private equity has become such a force in dermatology that job postings now emphasize when the business is “NOT private equity.”

Finally, private equity funds abuse the law to evade due diligence. They set up interlocking legal entities to make it more difficult to know whom to sue; they sue customers (often poor people who fall behind on loan payments or medical bills) who do not have any legal recourse to fight back. Companies are reorganized into, say, one that manages real estate, one for equipment, one for staffing. Even if a single company still controls the profits, this restructuring reduces the assets that could be at risk for being seized to pay damages in the event of a malpractice suit. In a sense, this fits with the overall model of private equity, in which the obligations of ownership disappear into an endless shell game of holding companies.

Morgenson, Rosner, and Ballou offer a damning indictment of private equity, but aren’t many of these issues—low wages, exploitation, the desire to escape regulation—aspects of capitalism generally?

Certainly it is true that private equity emerges out of the same kinds of trends that have increased economic inequality and insecurity for working- and middle-class people over the past fifty years. But aspects of its rise are uniquely troubling. The underlying ethos of private equity is that of separation and privatization: in a way, financiers seek to remove the firms they purchase from the prying eyes of society. In so doing, the industry draws on a romantic ideal of entrepreneurship. By taking firms private, financiers are supposed to be reinventing them with the panache available only to those who have a direct financial stake—whose own wealth is on the line.

Yet takeovers allow financiers to evade not only the rules and regulations of the SEC but also the need to answer to a diverse range of shareholders, who might, at least in principle, represent a broad portion of the community and be able to press for certain kinds of changes. One example is in climate policy: as institutional investors such as banks have divested from fossil fuel companies, responding to calls for sustainability, private equity firms have swooped in to buy them while also purchasing companies that specialize in disaster cleanup, managing both to fuel climate change and to profit from its wreckage.

The underlying desire to remove a company from public view and democratic debate echoes the world described by Quinn Slobodian in his recent book, Crack-up Capitalism (2023): the myriad attempts of capitalists to take advantage of zones that exist outside of any democratic oversight, taxation, or public realm—like the Cayman Islands. Not content with controlling the public sphere in the manner of the Gilded Age elite, they seek to remove themselves from it altogether. Is it any wonder that an economic elite that emerges from the world of private equity should be so narrowly self-interested, as the journalist Doug Henwood has argued ours is—inhabiting a realm of private schools, private transport, and private finance, its ideology a cliché-ridden paean to personal prosperity as a sign of moral worth?

Although private equity justifies its existence through an appeal to the tough love of the astute entrepreneur, it depends on public policy. Tax law plays a critical part in making these funds profitable. The “carried interest” provision, for example, which allows most of the profits of private equity partners to be taxed at the lower capital gains rate rather than as earnings, is crucial to their self-enrichment. The industry has attained such loopholes through the assiduous cultivation of (that is, strategic donations to) political allies; many elected officials from both parties have gone to work at private equity firms upon leaving public office—the equivalent of ex post facto bribery. These are no pirates, bucking the rules to win their fortunes; they are technocrats who have mastered the system and turned it toward their own ends.

The authors of Plunder and These Are the Plunderers suggest many specific reforms that could curb the power of private equity: for example, Department of Labor regulations that would establish minimum staffing for nursing homes, so that private equity funds (or garden-variety nursing home operators, for that matter) could not press for cuts beyond what is safe; pressuring university endowments and public sector union pensions to seek other investments; and revising tax laws to end the carried-interest provision. Despite the merits of these commonsense proposals, they would be very difficult to execute. To win such changes, we likely would need to see a shift in political power similar to that of the early twentieth century, when the Gilded Age waned.

Ballou concludes by comparing the present crisis of American capitalism to the US at that earlier moment. Then as now, he reminds us, American democracy was endangered by the rise of unchecked corporate power, accompanied by political repression in both the North and the South: the crushing of labor unions and the white supremacist backlash against Reconstruction that culminated in disenfranchisement, lynchings, and the rise of the Second Klan.

Yet over the first decades of the twentieth century, social protest movements were able to challenge the elites of their day. In the Progressive Era and during the New Deal, they exacted reforms that mandated financial transparency. More than this, they created political institutions—including labor unions, regulatory agencies, and forms of corporate ownership that are more apt to be responsive to the public—that could pressure private capital to respond to the needs of the broader society. All these embodied the principle that the economy must serve a wide range of needs, not just the self-satisfaction of an elite.

This Issue

October 19, 2023

Heading Toward a Second Nakba

The Voyage Out

- In August 2023 the SEC adopted new regulations for private equity funds, mandating that they share quarterly reports with investors and be more transparent about fees. The new rules are facing legal challenges from the industry.