Jesuits have never been shy about naming schools and other institutions after “Ours” (as they refer to each other)—Loyola, Xavier, Gonzaga, Canisius, Marquette. I went to Campion High School, where I was on the Bellarmine Debating Society, before entering St. Stanislaus Seminary—all three of them named for Jesuit saints. So one might have expected the first Jesuit pope to take his papal name from a Jesuit saint; there are, conveniently, two called Francis—Saint Francis Xavier and Saint Francis Borja (general of the order from 1565 to 1572). But Jorge Bergoglio took his name from Francis of Assisi, who was not a Jesuit, not a pope, and not even a priest. This is not surprising, since Bergoglio was not on good terms with his fellow Jesuits before his election to the papacy—which was probably why he was made a cardinal by Pope John Paul II, who despised Jesuits. John O’Malley, S.J., the great Renaissance historian, suspects that the pope thought he was not getting “a real Jesuit.”

Despite all this, some are trying to make the pope a “typical Jesuit,” though that is a mythical beast. There are Jesuits of all sorts, some to be revered, some reviled; some good, others bad. A good one died last year, the peace activist Daniel Berrigan, S.J.—though some thought that he, too, was not a real Jesuit. One of his superiors said he was “in the order, but not of it.” If I were looking for a bad Jesuit, I would name Pietro Tacchi Venturi, S.J., the secret intermediary between Pope Pius XI and Mussolini—a thorough anti-Semite, an authoritarian schemer, and a sexual adventurer. Fortunately, there are recent books that bring these two men into better focus—The Berrigan Letters (correspondence between the brothers Daniel and Philip Berrigan) and The Pope and Mussolini, by David I. Kertzer.1 Tacchi Venturi figures largely in Kertzer’s book, and is given solo treatment in a forthcoming book by Kevin Madigan of the Harvard Divinity School.

Kertzer showed that there was a knot of powerful Jesuits in Rome before World War II who were enthusiastically anti-Semitic and pro-Fascist—the Jesuit Superior General Włodzimierz Ledóchowski, S.J., the editor of the Vatican newspaper Civilta Cattolica Enrico Rosa, S.J., Mussolini’s promoter Tacchi Venturi, S.J., and the Gregorian University theologian Gustav Gundlach, S.J. These four men conspired to quash Pius XI’s attempt to issue an encyclical against anti-Semitism.

Ironically, the idea for Pius XI’s encyclical came from another Jesuit, John LaFarge, S.J., an American who had published the book Interracial Justice in 1937. While ministering as a young priest to blacks on the Eastern Shore of Maryland, LaFarge was shocked to discover that his order had held slaves there. We have heard recently of the way Georgetown University saved itself financially by selling 272 slaves in 1838. American Jesuits were major slaveholders. The oldest, most beautiful building in the Missouri seminary I attended had been built in 1840 (just two years after Georgetown’s slave sale), using slave labor.

Pius XI, a voracious reader, read LaFarge’s book at a time when he was becoming anxious over Mussolini’s anti-Jewish laws. He asked LaFarge to draft an encyclical for him on European animus against Jews, on the lines of his book on American animus against blacks. He told LaFarge to keep the project secret, since he knew there would be attempts to block it in his own Vatican—the pope did not even disclose it to his secretary of state, Eugenio Pacelli, the man who finally destroyed the draft encyclical when Pius died in 1939 and Pacelli became Pius XII.

People familiar with more recent progressive Jesuits may be shocked to learn how reactionary many of them were in the 1930s. But even earlier, in the 1890s, Superior General Luis Martin, S.J., and the editor of Civilta Cattolica, Salvatore Brandi, S.J., were warm allies of Pope Leo XIII in his condemnation of religious pluralism as a heretical “Americanism.” The liberal archbishop John Ireland, a frequent target of Brandi’s criticisms, told a friend, “The Jesuits and their ilk are killing the church.”

When considering Jesuit history in general, one must make one large distinction—between pre-suppression Jesuits (1540–1773) and post-suppression Jesuits (1814–present). In the first period, Jesuits were often fruitful troublemakers in theology, education, and politics, which made various local authorities, both lay and clerical, expel them—until, at last, the Franciscan pope Clement XIV yielded to royal foes of the Jesuits and abolished the order. When a later pope, Pius VII, revived it in 1814, the church was still in a state of frightened reaction to the French Revolution, a fearful attitude the revived Jesuits followed and enforced for almost a century. A pope had suppressed them once, and could do it again.

Advertisement

For much of that second period, Jesuits were not so much good or bad as mediocre. An indication of that is John McGreevy’s dutiful new history of mainly lackluster Jesuits in America. The book has no direct mention of the fact that Jesuits were major slaveholders. It just admits that Jesuits by and large supported the Confederacy and that a man to whom McGreevy devotes an entire chapter of his book, John Bapst, S.J., refused to admit the Catholic convert Orestes Brownson into a Jesuit seminary because Brownson was an abolitionist.

American Jesuits of that time often reflected the defensive posture of an immigrant church (according to McGreevy, “of the twenty-five founding presidents of Jesuit colleges in the nineteenth century all but two were born outside the United States”) and reacted to anti-Catholic prejudice (Harvard Law School under President Charles Eliot refused to accept graduates of Jesuit colleges). One of the great Jesuit causes in this period was protecting Catholic children from the King James Bible, which was on the Index of (papally) Forbidden Books. In the spirit of Leo XIII’s condemnation of “Americanism,” students at the Jesuit school of theology in Woodstock, Maryland, were forbidden to celebrate the Fourth of July.

Like other American clergymen, Jesuits carved out a niche in the New World by building churches, staffing schools, conducting retreats and novenas, praying for miracles, and celebrating relics. Jesuits were particularly focused on a miracle to which McGreevy devotes another chapter—a miraculous cure in Louisiana that was used to canonize an undistinguished Belgian, John Berchmans, who in 1621 died at Rome’s Jesuit seminary, age twenty-two. The only thing he had to recommend him was posthumous miracles.

John Bapst, who protected his seminary from Orestes Brownson’s abolitionism, avidly collected and displayed over four hundred relics of saints, including “tiny fragments” from Berchmans’s body, along with “a nail that touched a nail used on the Cross.” Of course there were individual Jesuits of great compassion and self-sacrifice during this time. One of the wisest men I have ever met was Joseph Fisher, S.J., the superior of the Jesuits’ Missouri Province when I was in the seminary there. After he gave up that office, he went to Belize (then British Honduras) to build homes for the poor with his own hands, a mission that vice-presidential candidate Tim Kaine spent time in years later. But histories like McGreevy’s are not built from such inconspicuous materials.

John O’Malley argues that Jesuits after their restoration had lost the institutional memory of the adventurous early Society, whose vivid personnel he evoked in his 1993 book, The First Jesuits. The order was reborn sclerotic. But in his later book The Jesuits (2014), O’Malley shows how the early spirit has been revived, based on better study of retrieved archives. For a time, the restored Jesuits had half-believed in the public image of the order’s founder, Ignatius Loyola, as a military man who marshaled Jesuits as a hard-drilled army to defend the pope and fight Luther. But Ignatius, far from being this partisan disciplinarian of the soul, was a mystic with visions like those of another former soldier, Francis of Assisi. Francis and Ignatius both began their religious strivings by going on pilgrimage to the Holy Land.

When Ignatius had his first few followers, they thought they would begin their ministry in Jerusalem, for which they asked the pope’s blessing. Ignatius did not see his group as mounting some mass attack on European Protestants. He was for scattering them off. It was a centrifugal band, not a centripetal one. He sent his beloved fellow Basque Francis Xavier far off to convert “pagans” in India and Japan. Naturally, such a footloose body, not subordinated to bishop or abbot, not tied to cathedral or monastery, would be suspect to some. Ignatius tried to forestall such resistance by pledging his men to follow the pope’s directives on their missions and by encouraging his followers to “think with the church.” And he made a deepening of spirituality the preparation for spreading the faith.

He did this through his Spiritual Exercises (exercitia means “workout”), a monthlong retreat made one-on-one with a personal trainer. The Exercises are now treated as a kind of spiritual boot camp to be experienced by incoming Jesuit seminarians in a group under one director—I went through it with about sixty fellow seminarians in a class swollen by 1950s religiosity. Ignatius, by contrast, thought of the month-long sessions as tailored to a single person—the “exercitant”—with his own (separate) director. This was a prolonged form of self-exploration, somewhat like the relation of psychoanalyst with patient. Ignatius even treated “spiritual discernment” as working through patterns of “consolation” and “desolation.”

Advertisement

The program was flexible, tailored to the pace, needs, and progress of the individual, to accord with his particular “age, education, and ability.” Speaking of the four weeks envisioned, O’Malley writes:

“Week” was actually an indeterminate period to be expanded or contracted according to the needs of the individual and the matter under consideration, so long as in their entirety the four Weeks did not exceed about thirty days.

The Exercises lie behind the modern practice of a “retreat”—withdrawal from one’s daily routine and patterns to consider their broader setting, possibilities, or shortcomings. Corporate and legislative bodies now encourage such retreats for secular purposes. Ignatius, of course, wanted to have a person reconsider his whole relationship with God.

In the first “week” one considers one’s isolation from God (which is the essence of sin). In Ignatius’s reorientation of his own life, on which he modeled the Exercises, he was brought to the edge of suicide in this contemplation of his isolation from God—a development the director must guard against. But relief comes in the second “week,” when one is called to enter into Jesus’s early life, imagining each event by a “composition of place” that makes the exercitant present with Jesus at every scene. The third “week” takes one through the passion and death of Jesus, and the fourth through his risen life in the church. Daniel Berrigan was never more Jesuit than when he responded to a friend who had asked him for advice: “Make your story fit into the story of Jesus. Ask yourself: does your life make sense in light of the life of Jesus?”

The Society of Jesus (Compagnia di Gesu) is based as an order on the closeness to Jesus wrought by the Exercises. Compagnia does not mean “company” in a military sense but comradeship. Other orders are named for their founders—Augustinians, Benedictines, Franciscans, Dominicans. But Jesuits were never Ignatians. They were comrades of Jesus. Some thought it arrogant to claim such closeness, but Jesus said that what was done to his “brothers” was done to him (Matthew 25:40). Though a profession of closeness to Jesus is common among evangelicals, Catholics have tended to use “Christ” more often than “Jesus,” since Christ (anointed messiah) is a title, not a personal name, and the title is more appropriate to a hierarchical church of many officials. This is one of many ways that Jesuits seemed too like the “individualist” reformers against whom they were supposed to be pitted.

The post-suppression Jesuits for a long time used the Exercises in a mechanistic way. They even conceived of Jesuit training as the Exercises writ large—a long retreat of fourteen years instead of one month. The novitiate, a two-year withdrawal from “secular” life (no newspapers or “nonspiritual” books) was like Week One. Away from “secular” books, we novices read vapid saints’ lives, heavy on miracle stories and repentance for sin.

After that, aspiring Jesuits studied the liberal arts for two years (juniorate), then philosophy for three years (philosophate), after which they taught high school for three years (regency), then studied theology for three years (theologate), at the end of which one was finally ordained a priest. But even then there was a further year (tertianship), taking the month of Spiritual Exercises again and trying out life as a priest.

This grueling process has been shortened and reconsidered in the modern order, where there are fewer Jesuits to be trained and they often enter at a later age. Dan Berrigan, who did the fourteen-year program, looked back on its expenditure of a person’s twenties-and-a-little-more as a waste of the idealistic youth he encountered in the peace movement and other causes. It also put off to the end real study of the New Testament (theology) that should be the motivation of a Christian. The Jesuits’ revised training is closer to Ignatius’s way of testing novices in active work with the poor, the sick, the disadvantaged.

When I asked Dan Berrigan if he thought of himself as a Jesuit, he answered in ways that showed he went back to pre-suppression days, closer to Ignatius. He has written, “We latter-day Jesuits, lesser sons of giants, are grateful for a mere gleam of greatness.” He mentioned Jesuits like Sebastien Rale, S.J., who protected Native Americans in the eighteenth century from tricks played on them to purchase their land. Puritans in New England put a price on Rale’s head, which was collected by bounty hunters bringing them Rale’s scalp. He also admired the Jesuits who used settlements called “Reductions” in eighteenth-century Paraguay to protect Native Americans from Portuguese slave raiders—Berrigan served as an adviser to the movie The Mission, made of this story by Roland Joffe in 1986. Berrigan described this experience in a book whose dedication reads “To the Jesuits for life.”

When Berrigan went to Colombia to make the movie and met Jeremy Irons, who plays the spiritual leader of the Reduction, he took him aside to give him an abbreviated (thirty-six-hour) version of the Spiritual Exercises, and they continually talked about Jesuit spirituality in the three months they spent together. The movie has its own take on the good Jesuit/bad Jesuit phenomenon. The bad Jesuit is played by Robert De Niro, a military man who cannot give up his violent ways after he joins the order. Joffe consulted with Berrigan on the history of the Jesuits, and Berrigan even persuaded Joffe to change the ending of Robert Bolt’s script, to strike just the right blend of resistance and nonviolence.

The movie cast knew about Berrigan’s avoidance of arrest while the FBI hunted him for four months in 1970 for destroying draft files, and they compared this with the story they were making of the way Jesuits defied slave hunters in eighteenth-century Paraguay. J. Edgar Hoover put Berrigan on his Most Wanted list, but Berrigan kept popping up at antiwar sites and writing to various outlets. (His “Letter from the Underground” appeared in these pages, August 13, 1970.) An exasperated William F. Buckley even frothed at the FBI for not nabbing Berrigan: “It was much likelier that you would see him on Johnny Carson’s show, thumbing his nose at American jurisprudence, than behind the bars he belonged behind.”

This escapade reminded me of another Jesuit’s evasion of a manhunt—Edmund Campion’s underground ministry to Catholics in Elizabethan England. Campion, too, infuriated the authorities with writings from the underground, and he avoided capture for a full year, by a manhunt far more extensive than that of 1970. Berrigan was justifiably unwilling to compare himself with Campion; he, after all, was not going to be killed when caught. Besides, Campion was an academic star (which Berrigan surely was not) and a renowned figure throughout Europe. Another reason Berrigan shied away from comparison with the Elizabethan Jesuits is that he knew some of them were contriving the overthrow of the queen, while his actions were not meant to overthrow the American government but to persuade it to give up its nuclear war plans. I argued that Campion was not one of the Jesuit traitors, but Berrigan still did not want to pursue the subject.

Still, I remained interested in Campion—and not simply because I went to a high school named for him. I read there Evelyn Waugh’s well-wrought and moving biography of Campion. In fact it was one of two books that prompted me to enroll in a Jesuit seminary. (The other was James Broderick, S.J.’s two-volume life of Cardinal Robert Bellarmine, S.J.) Waugh took the basic facts of his Campion book from Richard Simpson’s life of Campion (1876) while discarding Simpson’s thesis.

Simpson was a Victorian Catholic layman, the close friend of John Henry Newman and Lord Acton. The three of them collaborated on The Rambler, a liberal Catholic journal that opposed the ultramontanism (papal-centeredness) of the official church in nineteenth-century England. When The Rambler came under fire from Cardinal Nicholas Wiseman, who complained of it to Rome, the three men began a successor journal, The Home and Foreign Review, each serving as editor in turn, until it, too, was condemned. After the closing of the Review, Simpson concentrated on his life of Campion, a well-researched volume with a polemic subtext. Simpson argues that Campion, who was opposed to the Vatican attempts to overthrow the queen, came back to England to serve Catholics with the sacraments, but disagreed with the Jesuit he accompanied, Robert Persons, S.J., who meant to stir up rebellion. Simpson says that this division in the goals of the mission rightly doomed it to failure.

Waugh began his Campion book with a prolonged sneer at Queen Elizabeth, something Campion would never have done. Waugh, a recent Catholic convert when he wrote the book (1935), sympathized entirely with the ultramontanists Simpson was fighting—he writes that he will omit all of Simpson’s “Cis-Alpine pleading…tedious to modern readers.” Now comes a major biography of Campion by Gerard Kilroy, who discards Waugh and vindicates Simpson. Kilroy calls his book Edmund Campion: A Scholarly Life, and I took that at first to mean that Kilroy’s own book is a scholarly effort—and it certainly is. Kilroy spent years searching public archives and private collections for every aspect of Campion’s life and times. (Unfortunately he whips up a blizzard of evidence, which he does not sort out in easily assimilable ways.) But no, the title means that Campion led (or wanted to lead) a scholar’s life—until it was broken off by the pope and his Jesuit superior, Everard Mercurian.

Kilroy shows that Campion was happiest during his six years as a scholar at the Jesuit college (Clementinum) in Prague. Kilroy, drawing on letters by and about Campion at this period, says it was “the most demanding, and the most glamorous, phase of his life.” This is what Waugh calls the humdrum time when Campion submitted to “the sombre routine of the pedagogue.” Campion was teaching Cicero to his Latin class and Aristotle to his Greek class, and putting on plays of his own composition for the citizens of Prague and for the lively court of Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II, where he became a favorite. Waugh, following hagiographical convention, says that Campion was eager to go back to a martyr’s death in England. Kilroy proves that Campion left Prague reluctantly, delayed his trip to Rome after being summoned, tried to get the pope to loosen the obligation of English Catholics to deny the legitimacy of Elizabeth, and refused to be the leader of the mission to England. His letters show that he feared his own cowardice (ignavia) would disgrace him.

Campion was no coward, as he would prove. But neither was he a fool. And he was being sent on a fool’s errand. The Jesuits were to go back to their native England on the pretense that supplying the sacraments to Catholics had nothing to do with subversion of the queen’s Protestant government. In 1570, Pope Pius V, in the bull Regnans in Excelsis, had excommunicated Queen Elizabeth and released Catholics from obedience to her, hoping that would end her reign. Waugh treats Pius V, a Dominican ex-Inquisitor, as a holy fool with supernatural guidance. But ten years later, when the queen was not unseated, Campion tried to get a later pope, Gregory XIII, to ease the demand that Catholics disobey her. The pope could not do that, Kilroy says, because he had already dispatched troops that were invading Ireland and he could not imperil their cause. Kilroy calls Campion’s assignment

the criminal folly of sending the English Jesuit mission into a country that was already facing the two greatest horrors for the Elizabethan state: rebellion and invasion under a papal banner…. When Campion landed in England, he might as well have walked onto a battlefield carrying [nothing but] an umbrella.

What Waugh did not see (or want to) is how Simpson “carefully distinguished Campion’s spiritual aims from the political aims of [seminary director Richard] Allen, Persons, and the papacy itself.” Campion died not for what he did, but for what his superiors did.

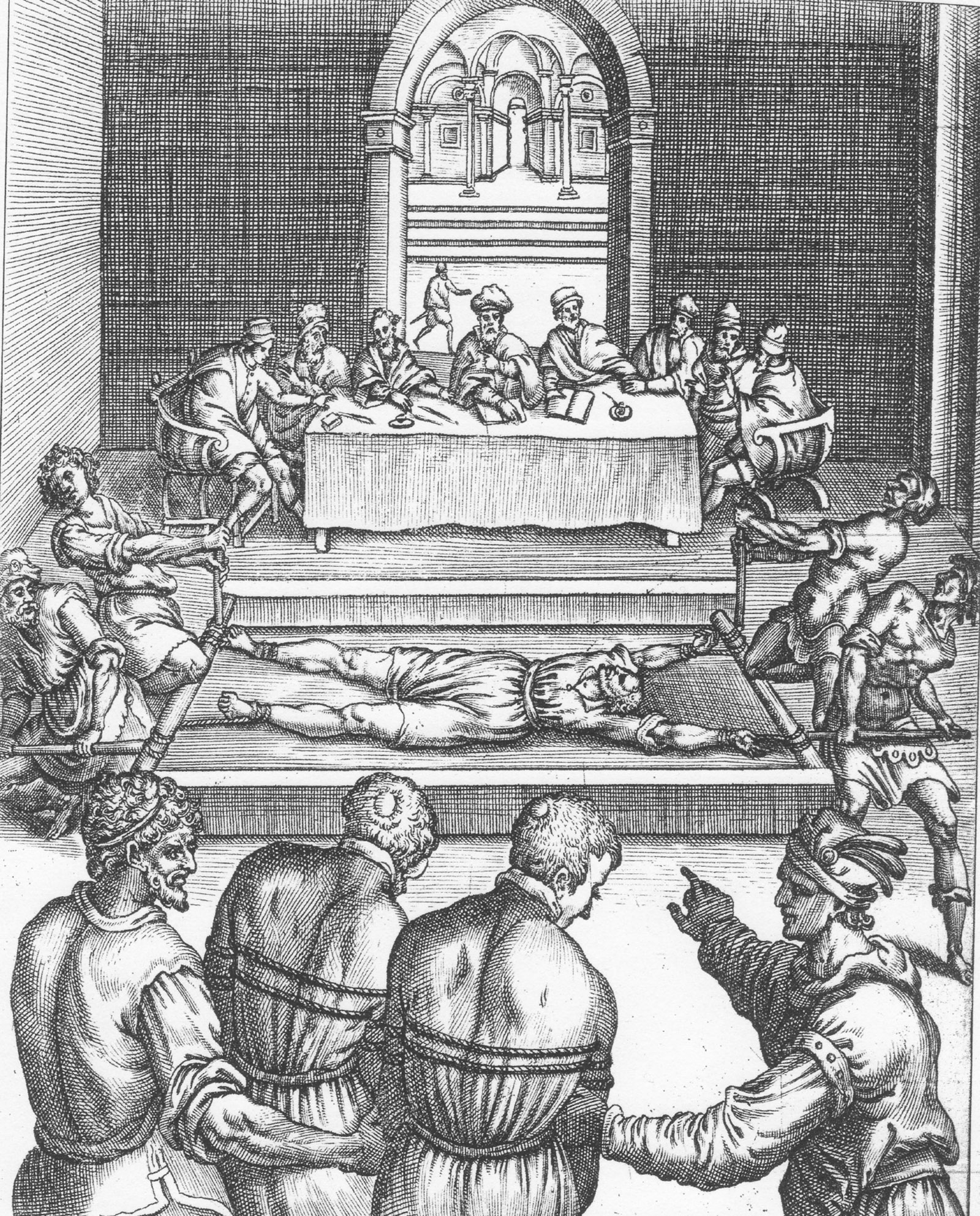

He knew that he would not only suffer a horrible death but would be tortured before being killed. All Europe was aware that Britain had recently resorted to torture, which was against the common law and British practice, because the government was hysterical with panic owing to the papal-inspired threat from “the enemy within.” Legal authorities like Francis Bacon and Edward Coke justified this, as John Yoo and David Addington did in the Bush administration, on the grounds that the urgency to know what terrorists were planning was more important than gathering evidence for any trial of a captive (since coerced testimony cannot be used at trial). In Bacon’s words, “Torture is used for discovery and not for evidence.”

When Campion was captured after a year ministering secretly to Catholic Englishmen, he was given harsher and longer tortures than others. He was the biggest fish caught in Elizabethan nets. (There would be a bigger one under King James, when Henry Garnet, S.J., was executed for his involvement in the Gunpowder Plot.) He was important enough to be secretly taken to the Lord Keeper’s residence, York House, where the queen personally offered him a bishopric in the Church of England if he would recant.

When that did not work, the tortures were resumed. He was racked so forcibly as to dislocate his limbs—at his later hearings, he could not raise his arm to take an oath. His bandaged hands could not turn book pages because “nails were thrust between his nails and the quick.” To give Campion’s torturers immunity from punishment, they had to have a special warrant from the court. The Earl of Leicester, who had favored Campion when he was proctor at Oxford, issued four such warrants (more than for any other prisoner) to torture Campion repeatedly.

In his agony, Campion did give up, at intervals, information about the Catholic houses that had sheltered him while he was underground. Simpson and Waugh claim he revealed nothing of significance, but Kilroy shows that the houses he named were ransacked, for Catholic books and other clues, and their owners were interrogated about other Catholic activities. Campion repented afterward that he had named names, which Simpson and Waugh minimize as his saintly exaggeration of slight failings.

Kilroy rightly takes Campion at his word—he did expose his protectors, and the torturers had reason to think they had succeeded in uncovering Catholic plots. This vindicated their reliance on torture, perhaps the worst result of Campion’s lapse. He clung to the comfort that he had not given up any information that he received in sacramental confession, but he did unleash the police on all the houses he had mentioned. He is heroic enough that he needs no whitewashing.

Campion suffered the usual death for convicted traitors. He and two others were didactically dismembered at the Tyburn gallows—hanged, their hearts ripped out, heads axed off, then both arms and both legs—muscular men required in the chopping. The scaffold was slopped and slippery with blood and human meat. Men were set to guard the mess, since Catholics would try to take off relics (a man, in the melee, got one of Campion’s fingers). Some Catholics on the scene were inspired by Campion’s courage. The late Joseph Kerman conjectured, in these pages, that the great musician William Byrd was one of them, since he paid tribute to Campion in later compositions.2

Berrigan was no Campion. His life and work are not on that scale. Still, America magazine was probably right to give him its 1988 Campion Award for literary-spiritual excellence. Like Campion, Berrigan was a poet and playwright. Like Campion, he feared his own ignavia. Campion tried to avoid going to England. Berrigan, urged by his priest-brother Phil to join him and three others in destroying Baltimore draft files, refused to go with them. But he regretted that decision, and went with them a year later, when the Baltimore Four became the Catonsville Nine. After that, the brothers were reciprocally supportive in many actions.

Some of their critics may expect the brothers’ extensive correspondence, just published, to talk of plots against the government. In fact, they trade encouragement, consolation, and prayers. Some letters are sent into or out of prison, depending on which brother was where after a demonstration (the letters even go from one prison to another when both are serving time). The two men bolster each other’s resolve. They consider how to put up with their bullying father. They coordinate support for their pious mother. Each admires the other’s different talents and endeavors. Dan did not go to jail as much as Phil, and praised what he felt was his younger brother’s greater courage. In Colombia to work on the movie The Mission, he worries about Phil’s latest trial: “I keep hoping, in my lily-livered way, that he is not locked up.”

As for the burning of draft files, to prevent sending young men into the sinkhole of a war in Vietnam, that makes me think of the crowd of Catholics who, at the death of the inquisitor-pope Paul IV in 1559, broke into the office of the Roman Inquisition and destroyed its files, sparing the victims of persecution. The Berrigan brothers’ later destruction of nuclear symbols makes me think of a story about Pedro Arrupe, S.J., who was the superior general of the order from 1965 to 1983. O’Malley says that Arrupe, a Basque like Ignatius, “became perhaps the most beloved and admired general of the Society with the exception of Ignatius.” The editor of Berrigan’s writings, John Dear, reports that a Canadian priest recognized Arrupe in Rome and greeted him. Arrupe asked if the priest was a Jesuit. No. Did he know any Jesuits? Yes, Dan Berrigan. Arrupe said, “Daniel Berrigan is the most faithful Jesuit of his generation.” What makes this story plausible for me is Arrupe’s hatred of nuclear arms. He was present at Hiroshima when the bomb was dropped, and he used his early medical training to work with victims there.

The Berrigans seem also to fit Pope Francis’s ideal of priests who work with the poor and excluded, “on the margins.” Phil Berrigan joined the Josephite order, not the Jesuits, because their mission was especially to African-Americans. He and Daniel marched with Martin Luther King Jr. and worked in hospitals for the poor. When the AIDS crisis hit in the 1980s, Daniel was one of the first priests who ministered to its victims. He admitted that he hated going to prison, but he felt that he had to go there, since that is where he and Phil met Jesus in “the sisters and brothers of the divine Prisoner.”

When Phil died in 2002, I went back to Baltimore for his funeral. It was in a rundown area where Phil had been a pastor, and blacks came out for it after the workday. They could see his body laid in a bare wood box. Dan conducted the funeral Mass and preached the homily, telling the story of Lazarus as a sign of life rising out of deathlike conditions. Looking at people like Berrigan and Arrupe and Francis, I think it safe to say we live in an era of good Jesuits. Now there are some giants on the shoulders of giants.

This Issue

February 9, 2017

Was Snowden a Russian Agent?

The F Word

Trump & the World

-

1

Reviewed in these pages by Alexander Stille, April 23, 2015. ↩

-

2

Joseph Kerman, “William Byrd and the Catholics,” The New York Review, May 17, 1979. ↩