In the summer of 1902 the American novelist Willa Cather set off from Pittsburgh for Europe with her friend Isabelle McClung. Soon after docking at Liverpool they excitedly embarked on a literary pilgrimage to an English county that had hitherto rarely featured in Americans’ European itineraries. “When we got into Shropshire,” she wrote to her friend Dorothy Canfield from Ludlow on July 6, “we threw away our guide books and have blindly followed the trail of the Shropshire Lad and he has led us beside still waters and in green pastures.” From Ludlow they visited other locations mentioned in A Shropshire Lad (1896), the celebrated cycle of sixty-three poems by the English classicist and poet A.E. Housman. They went to Shrewsbury and Knighton, as well as the rivers Ony and Teme and Clun, invoked in the opening lines of the fiftieth poem in the sequence (“In valleys of springs of rivers,/By Ony and Teme and Clun”).

Housman’s lyrics ringing in her head, Cather was delighted to find boys playing soccer on the banks of the Severn, as they do in poem XXVII (“Is football playing/Along the river shore,/With lads to chase the leather,/Now I stand up no more?”); also to note that the jail in Shrewsbury was indeed close to the railway tracks, as indicated in poem IX:

They hang us now in Shrewsbury jail:

The whistles blow forlorn,

And trains all night groan on the rail

To men that die at morn.

One afternoon she and McClung rented bikes and pedaled happily off to the forested limestone escarpment known as Wenlock Edge—“On Wenlock Edge the wood’s in trouble” (XXXI); “Oh tarnish late on Wenlock Edge,/Gold that I never see” (XXXIX). She was even inspired to write a sub-Housman set of quatrains herself, about the poppies growing on the top of “Ludlow keep.” “I’ll not quit Shropshire till I know every name he uses,” she exclaimed to Canfield. “Somehow it makes it all the greater to have it all true.”

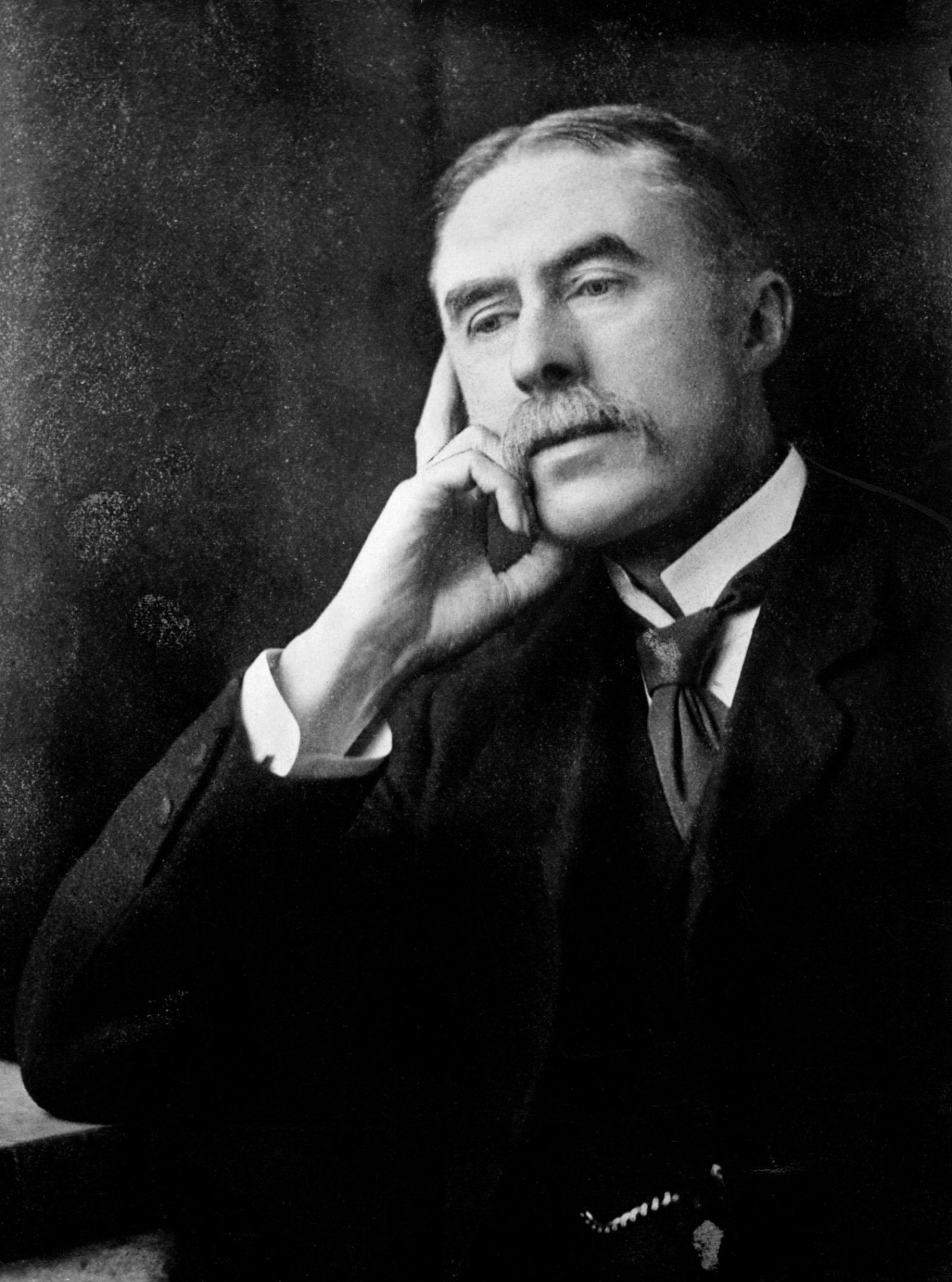

Cather, alas, decided it might also prove rewarding to seek out in person the author of the poems that had so enchanted her. As Peter Parker notes in Housman Country, his new study of the poet’s work and influence, Housman (born and bred in neighboring Worcestershire) didn’t in fact know Shropshire particularly well; he had quarried the details so admired by Cather from Murray’s Handbook, which was perhaps one of the guidebooks that Cather had discarded in favor of A Shropshire Lad. While staying in London she “battered on the doors” of Housman’s publishers until they reluctantly furnished his address, then triumphantly set off in pursuit of her idol.

Housman’s residence at this time was 1 Yarborough Villas in far-flung Pinner, which Cather discovered to be “an awful suburb” toward the end of the Metropolitan Line in northwest London; there she found the singer of the rivers of Ony (nowadays Onny) and Teme and Clun residing “in quite the most horrible boarding-house ever explored.” The visit, needless to say, was not a success; even “the state of the carpet,” Cather reported, “in his little hole of a study gave me a fit of dark depression.” The immortal bard of Shropshire struck Cather as “the most gaunt and gray and embittered individual” she had ever met. His shoes and cuffs were in a poor state. Brusquely ignoring her attempts to engage him in discussion of his poetry, he deftly maneuvered the conversation into “safe and impersonal channels.” Afterward Cather was apparently so upset that she burst into tears.

Housman (1859–1936) was himself acutely aware of the dramatic disjunction between his poetry and his life. He once observed that some authors are more interesting than their books, but that his book was more interesting than he was. In “The Name and Nature of Poetry” (1933), a lecture given at Cambridge near the end of his life, Housman described writing poetry as a “passive and involuntary process” and compared his poems to a “morbid secretion, like the pearl in the oyster.” Lines or stanzas would come to him on walks, often after he’d had a pint of beer with his lunch, “with sudden and unaccountable emotion,” and their source was not his brain, but “the pit of the stomach.” It was vital, in other words, for Housman to view his Muse as beyond the control of his conscious intentions, to think of himself as a mere vessel to be visited by his interior paramour, to borrow a term of Wallace Stevens, when and where she chose. His poems would “bubble up,” as if concocted by the gods of the imagination in the cauldron of his digestive system.

While Housman was by no means unique in embracing this approach, I think it fair to say that he was unparalleled in the thoroughness with which he resigned himself to a passive vision of creativity. (W.B. Yeats, who loved to assert and dramatize the power of his own poetic will, would stand at the opposite end of the spectrum.) Among other things, this extreme self-abnegation meant, as Cather found to her consternation, that Housman was extremely reluctant to discuss his work; as with his homosexuality or his hopeless lifelong love for his very unhomosexual Oxford classmate Moses Jackson, he clearly experienced his poethood as a nonnegotiable fact to which he must unconditionally submit. Only in his late Cambridge lecture does he reveal, and in a manner provocatively designed to strike his academic audience as verging on the philistine, the conditions that allowed him to evade his rigor and intellect and write the poetry that made him famous.

Advertisement

As a classical scholar Housman was renowned for his excoriating denunciations of the stupidities of fellow or earlier editors of Latin texts, but to create his own poetry he evidently had to lull to sleep his acerbic, judgmental impulses. Illness seems to have helped in the relaxation of his critical faculties: in “The Name and Nature of Poetry” he remarks, “I have seldom written poetry unless I was rather out of health,” and he once attributed much of A Shropshire Lad to a persistent sore throat. It’s hard not to imagine Housman’s experience of the arrival of the Muse as analogous to the overpowering feeling depicted in one of his most famous quatrains:

Into my heart an air that kills

From yon far country blows:

What are those blue remembered hills,

What spires, what farms are those?

Commentators and admirers have often sought to discern a buried narrative or secret pattern in the lyrics collected in the book. Parker is clear that all such attempts are doomed. Nor is it easy to characterize the Shropshire lad himself—initially Housman intended to call the book Poems by Terence Hearsay, who features in poem LXII; he changed his mind and opted for A Shropshire Lad only at the last moment. What shape or story the volume presents derives from poems such as XXXVII, which describes a train journey from “the wild green hills of Wyre” and “the high-reared head of Clee” to London; or XLI, in which the transplanted country lad walks the streets of the capital, musing on the shire he left.

While the poems are all freestanding, they are linked not only by their shared meters and rhymes, but by their persistently morbid themes. A number tell condensed, often grisly stories: in poem VIII the speaker kills his brother Maurice, leaving his corpse in a hayfield, while in IX the speaker’s friend is about to be hanged (in the jail in Shrewsbury near the railway line). In the most gruesome, LIII, a lover lures his beloved to join him outdoors one starlit night, only to reveal that he has cut his own throat. Here the closeness of Housman’s effects and tone to traditional ballads is especially striking:

“Oh lad, what is it, lad, that drips

Wet from your neck on mine?

What is it falling on my lips,

My lad, that tastes of brine?”

“Oh like enough ’tis blood, my dear,

For when the knife has slit

The throat across from ear to ear

’Twill bleed because of it.”

Not all Housman’s Shropshire lads die so sensationally; some find an early grave by natural, or undisclosed, causes, while others enlist and perish in foreign parts.

Most of the poems were written in 1895, when Housman was living in Highgate in north London. The book was published by Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co. early the following year, with Housman contributing £30 to cover costs. Its popularity was not immediate: by the end of 1896 only 381 copies out of a print run of 500 had been sold. It was not until the volume was reissued in 1898 that this unlikely sleeper slowly but steadily began to find a receptive audience. By 1911 it was selling in a variety of formats at the staggering rate of 13,500 copies a year. Composers such as Vaughan Williams and George Butterworth vied with each other to set its lyrics to music, while for many caught up in World War I A Shropshire Lad came to signify all that was precious in England and Englishness. Housman’s lyrics, as Parker illustrates in meticulous and compendious detail, were taken by many soldiers to encapsulate a vision of the nation’s landscape and values worth defending at all costs.

It is, of course, fitting that A Shropshire Lad became popular with young men in the trenches, since many of its poems concern soldiers and violent death. “Shot? so quick, so clean an ending?” opens XLIV. But the particular soldier this poem invokes was not one of those who came to grief on the Empire’s frontiers or in colonial skirmishes in Asia or Africa. In Housman’s own copy of A Shropshire Lad the poet’s brother Laurence found tucked next to this poem a newspaper article dated August 10, 1895 (the year of the trial of Oscar Wilde), describing the inquest into the death of a nineteen-year-old Woolwich cadet named Harry Maclean.

Advertisement

The article cut out and preserved by Housman reports how a week earlier Maclean had come up to London, taken a room in the Charing Cross Hotel, and then shot himself in the head. He left behind a suicide note that the poet clearly had no trouble decoding—indeed a sentence from it captures pretty much exactly his own impossible relationship with Moses Jackson: “There is only one thing in this world that would make me thoroughly happy; that one thing I have no earthly hope of obtaining.” The poem, with what degree of irony it is not easy to judge, commends the young cadet’s decision to kill himself and thus escape the contumely heaped earlier that year on the convicted Wilde:

Shot? so quick, so clean an ending?

Oh that was right, lad, that was brave:

Yours was not an ill for mending,

’Twas best to take it to the grave….

Oh soon, and better so than later

After long disgrace and scorn,

You shot dead the household traitor,

The soul that should not have been born.

Housman’s sense that he himself also harbored a “household traitor” was evidently a vital impulse for his periodic bouts of poetic composition. In a letter written just a few weeks before Jackson died of stomach cancer in 1923, Housman went so far as to suggest that it was his friend who was “largely responsible” for the poems collected in A Shropshire Lad and Last Poems, which he hurried into print so that Jackson could read the book on his deathbed. The lines and verses that bubbled up from the pit of Housman’s stomach were, it seems clear, his way of dealing with the emotions that might otherwise have tempted him to commit suicide like Maclean, or to risk “disgrace and scorn” like Wilde. They also allowed him to forge momentary metaphorical links with others whom he imagined to be in the same situation; some of his most moving stanzas are those that reach out from the page to their addressee, though he is often, like Maclean or the athlete who dies young in XIX, in the grave:

Turn safe to rest, no dreams, no waking;

And here, man, here’s the wreath I’ve made:

’Tis not a gift that’s worth the taking,

But wear it and it will not fade.

The nonbelieving Housman knows that the brave cadet will never wake; and yet, in the grip of the poem’s fantasy, directly addresses him, with appropriate amounts of self-deprecation and English reserve, across the impassable gulf.

Parker’s Housman Country is partly about the contemporary events and personal griefs refracted in A Shropshire Lad, and partly about the history of the work’s reception: he explores the appeal of Housman’s exquisitely chiseled quatrains to readers from Winston Churchill to Tom Stoppard (whose 1997 play The Invention of Love unfavorably contrasts Housman’s repression and timidity with Wilde’s reckless flamboyance); from Vaughan Williams and George Butterworth to Morrissey of the Smiths, whose morose lyrics reprised for the late twentieth century Housman’s melancholy fusion of stifled longing and inevitable disaster.

Parker is particularly interesting on the intersection of Housman’s mournful portrayal of Shropshire as “the land of lost content” with the elegiac strain in myths of Englishness. The opening poem of A Shropshire Lad, “1887,” is ostensibly a celebration of Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee, but its patriotic tribute to her reign is quizzically balanced by the references Housman makes to all the soldiers buried in foreign parts:

It dawns in Asia, tombstones show

And Shropshire names are read;

And the Nile spills his overflow

Beside the Severn’s dead.

The distant graves of these Shropshire-born soldiers perform a kind of initiatory rite of sacrifice: if their deaths have helped make possible the Empire, they are also shown to license the pastoral myth of Englishness explored in A Shropshire Lad itself; indeed they disconcertingly foreground the importance of such myths to the ideology of British imperialism. Housman, it should be noted, deliberately presents his rural landscapes in a way that is largely abstracted—his Shropshire has none of the particularity and historical layering of Thomas Hardy’s Wessex. It is a country of the mind, a nostalgic national fantasy explicitly exposed as such, and yet one that also inspires genuine feeling and even, as “1887” and poems such as “The Recruit” and “Reveille” demonstrate, provokes a desire to participate in the imperial mission. The hills of provincial Shropshire achieve their lyric and pastoral potency—become, that is, the “blue remembered hills” of “yon far country” (XL)—only because many have left them tragically for elsewhere: for the imperial center, London, to which the Shropshire lad himself is exiled, or for conquered realms beside the Nile or in Asia.

It was to Karachi, which was then in India, that Moses Jackson departed in December 1887 (it is surely no coincidence that A Shropshire Lad opens with this date), to take up an appointment as principal of Dayaram Jethmal Sindh Science College. Jackson and Housman had met eight years earlier as students at Oxford, where they shared lodgings in St. Giles’, just opposite their college, St. John’s. Housman had early established himself as an extremely talented student of Latin and Greek, gaining high marks in his first-year exams; a promising academic career seemed to beckon—until he utterly failed his final exams. It has never been ascertained whether this unaccountable disaster was the result of some violent emotional upheaval brought on by his attraction to the athletic, hearty Jackson, a no-nonsense student who had come to Oxford on a science scholarship. Whatever the disturbance, it didn’t affect Jackson, who was awarded a first.

Undeterred by this setback, Housman found a job at the Patent Office in London and spent his evenings pursuing his classical studies in the British Library, publishing and editing at such a rate that in 1892 he was able to apply for, and be appointed to, a professorship of Latin at University College London. He and Jackson again shared accommodations in 1883–1885, on Talbot Road in Bayswater. Jackson later moved to Maida Vale, where he met and fell in love with his landlord’s daughter, Rosa Chambers. They married during his first return from India in 1889. Rosa traveled back with Jackson to Karachi, and in due course gave birth to four sons, leaving Housman to ponder his unrequited “long and sure-set liking,” and eventually to compose poems in which his stiff upper lip, always elegantly mustached, is set violently aquiver:

Because I liked you better

Than suits a man to say,

It irked you, and I promised

To throw the thought away.

To put the world between us

We parted, stiff and dry;

“Good-bye,” said you, “forget me.”

“I will, no fear,” said I.

In a characteristic irony, at once reticent and barbed, we learn that this poem’s lad does indeed fulfill his promise, but only by dying:

If here, where clover whitens

The dead man’s knoll, you pass,

And no tall flower to meet you

Starts in the trefoiled grass,

Halt by the headstone naming

The heart no longer stirred,

And say the lad that loved you

Was one that kept his word.

Whereas in XLIV the living poet imagines himself addressing the dead cadet, here the narrator is figured as delivering a posthumous communication to the indifferent beloved at the site of his own grave. Given its explicitly homoerotic content, it is not surprising that Housman opted not to publish this poem in his lifetime, the “tall flower” of the third stanza being particularly open to a Freudian interpretation.

Parker ably charts the weird but potent energies of Housman’s poetic economy, and the peculiar, distinctly English way in which his work draws on the great romantic trope of the Liebestod, the consummation of love in death. As W.H. Auden noted in his savage but acutely perceptive sonnet “A.E. Housman,” it was Eros that entwined death and the poetic in Housman’s imagination. In the daydream of each set of rhyming quatrains, this ultimate union afforded a temporary respite from the complex barriers that the poet established between himself and those he dealt with in his regimented daily life:

In savage foot-notes on unjust editions

He timidly attacked the life he led,

And put the money of his feelings on

The uncritical relations of the dead,

Where only geographical divisions

Parted the coarse hanged soldier from the don.

It was just this kind of English repression, even hypocrisy, that Auden moved to America to escape, but Housman—like his successor as laureate of English unhappiness and unfulfillment, Philip Larkin—used his misery to create a body of poetry that sank, to borrow Parker’s subtitle, deep “into the heart of England.”

Housman also found comfort, or at least the poems often suggest he did, in the thought that while his secret anguish set him apart from those around him, it connected him not only to other “luckless lads”—i.e., young male readers of his poems facing similar quandaries—but to a chain of historical forebears. In XXXI (“On Wenlock Edge the wood’s in trouble”), he seeks solace for the inner turmoil symbolized by the heaving, wind-ravaged wood in the thought that, centuries earlier, a Roman may have stood and suffered in a similar manner on the very same spot:

There, like the wind through woods in riot,

Through him the gale of life blew high;

The tree of man was never quiet:

Then ’twas the Roman, now ’tis I.

While Housman possibly engages in such stoical reflections only to heighten the drama of his own suffering, the links that he posits with “others” do serve to challenge his solipsism, and create a sense of continuity and shared experience. XXX addresses the same theme:

Others, I am not the first,

Have willed more mischief than they durst:

If in the breathless night I too

Shiver now, ’tis nothing new.

Like his predecessors in pain, he will eventually find a resolution to his torment in death, although in fact in this particular poem—Housman’s most excruciating poetic evocation of a dark night of the erotic soul—the reflection provides only minimal relief:

But from my grave across my brow

Plays no wind of healing now,

And fire and ice within me fight

Beneath the suffocating night.

The hold of such poems on readers owes much to their memorability: the tripping tetrameters, the jingling rhymes that we associate with ballads or children’s verses or nonsense poetry, are here repurposed to present a harrowing confession of personal torment as extreme as that dramatized in John Donne’s “A Nocturnal Upon St. Lucy’s Day” or the dark sonnets of Gerard Manley Hopkins. Not a word is wasted.

Housman Country presents a comprehensive survey of the effect of such poems on successive generations. It must be acknowledged that certain chapters—such as the one on musical adaptations of Housman, or the final one on his presence in contemporary culture—read rather too much like a catalog, or a series of encyclopedia entries, and the book overall would have benefited from a stronger narrative shape. But many of the responses, tributes, and recollections unearthed by Parker are both striking and moving. Consider, for instance, the contemporary writer Maggie Fergusson’s account of her grandfather, a survivor of the trenches, sitting in old age at twilight with a tumbler of whisky while listening to Vaughan Williams’s setting of “Bredon Hill,” “playing the record over and over as tears streamed silently down his ruined face.” For numerous readers, as Parker demonstrates in rich and varied detail, Housman’s poetry both articulated and incarnated “the land of lost content.”