There is a certain irony in the fact that the first major retrospective of David Wojnarowicz’s work since his death in 1992 appears in the spare, modern rooms of the Whitney Museum of American Art, in Manhattan’s Meatpacking District, today one of the city’s trendiest neighborhoods. From the heights of the Whitney’s exterior staircase one can look down on the Hudson River and what were once the West Side piers, now devoted to bike lanes, parks, and ambitious development projects.

When Wojnarowicz lived and worked in New York, in the 1970s and 1980s, he spent much of his time in this neighborhood and on those piers, but it was a very different world. The piers, once berths for luxury cruise liners, had been abandoned and had become a refuge for transient artists, street people, and gay hustlers. Wojnarowicz was, at one point or another, all three. The Whitney exhibition features many striking photographs of him and his friends there, surrounded by graffiti, decay, and detritus.

Wojnarowicz died of AIDS-related complications at the age of thirty-seven, after just more than a decade as a visual artist. His wide-ranging work, beautifully displayed and carefully placed in its historical setting by the Whitney, is a testament to a New York characterized by urban decline, rampant crime, the AIDS crisis, and the culture wars, but also by ACT UP, the East Village art scene, Gay Men’s Health Crisis, Angels in America, and the transformation of the LGBT movement. Wojnarowicz’s work, by turns angry and elegiac, haunting and disturbing, subtle and in-your-face, chronicles that period by focusing on its outcasts and vividly depicting their lives, loves, and complaints. Certain pieces, including a photograph of a diorama of buffaloes stampeding off the edge of a cliff, have become famous. But seeing the work as a whole reveals an astonishingly prolific self-taught artist who worked feverishly in multiple media to give voice to the demands for justice—and understanding—of the marginalized.

Wojnarowicz knew firsthand what he depicted. As Cynthia Carr writes in her masterful biography, Fire in the Belly: The Life and Times of David Wojnarowicz (2012), he had an “almost Dickensian childhood.” Born in New Jersey in 1954 to an alcoholic, homophobic, and abusive merchant seaman and a hapless, overwhelmed mother, he was beaten and abducted by his father, and grew up between halfway houses, his mother’s tiny apartments, and the streets of New York. He started turning tricks as a gay hustler in his early teens and barely managed to graduate from the Manhattan High School of Music and Art. But he had remarkable talent, an adventurous spirit, and a keen eye for both the structural injustices of what he called the “pre-invented world” and the beauty to be found in its misfits.

The exhibition begins with his first major artwork: a series of black-and-white photographs of his friends in various parts of Manhattan wearing a mask of Arthur Rimbaud. Born exactly one hundred years before Wojnarowicz, Rimbaud also died at the age of thirty-seven and celebrated the outsider. Patti Smith described Rimbaud as “tramping the luminous sewer of his own circulatory system with all his marvelous contradictions intact.” For the series, Wojnarowicz depicted Rimbaud—who famously wrote “Je est un autre” (“I is an other”)—shooting up, eating at a late-night diner, standing before graffiti on the West Side piers, walking through Times Square, masturbating, and holding a gun in front of a faded wall painting of Christ. The mask gives the photographs an “everyman” quality, but the settings define him as living on the edge.

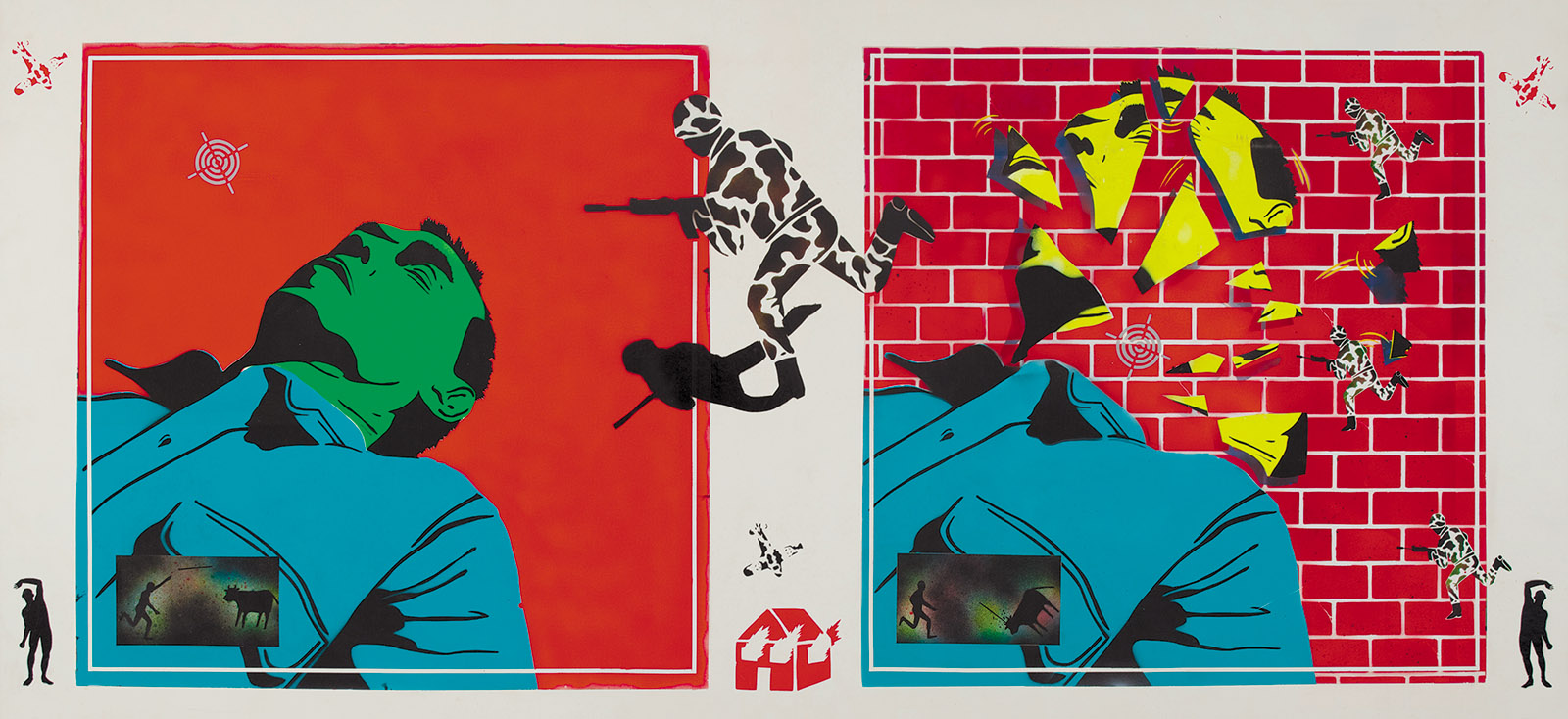

Wojnarowicz was polymorphously creative. He wrote poetry, journals, and political essays, the best of which are collected in Close to the Knives: A Memoir of Disintegration (1991). He was in a rock band, 3 Teens Kill 4. He stenciled, sculpted, painted, photographed, and made films. His work ranges from intimate self-portraits to vast canvases and collages in deep, vibrant colors teeming with cartoon-like violence, maps, sexual scenes, airplanes, animals, dollar bills, sheet music, burning houses, falling men, weapons, and unidentified machines. As Hanya Yanagihara writes in the exhibition catalog, in his work “you can feel the presence of someone for whom there is no fear of breaking the rules, because he has never been taught the rules to break.”

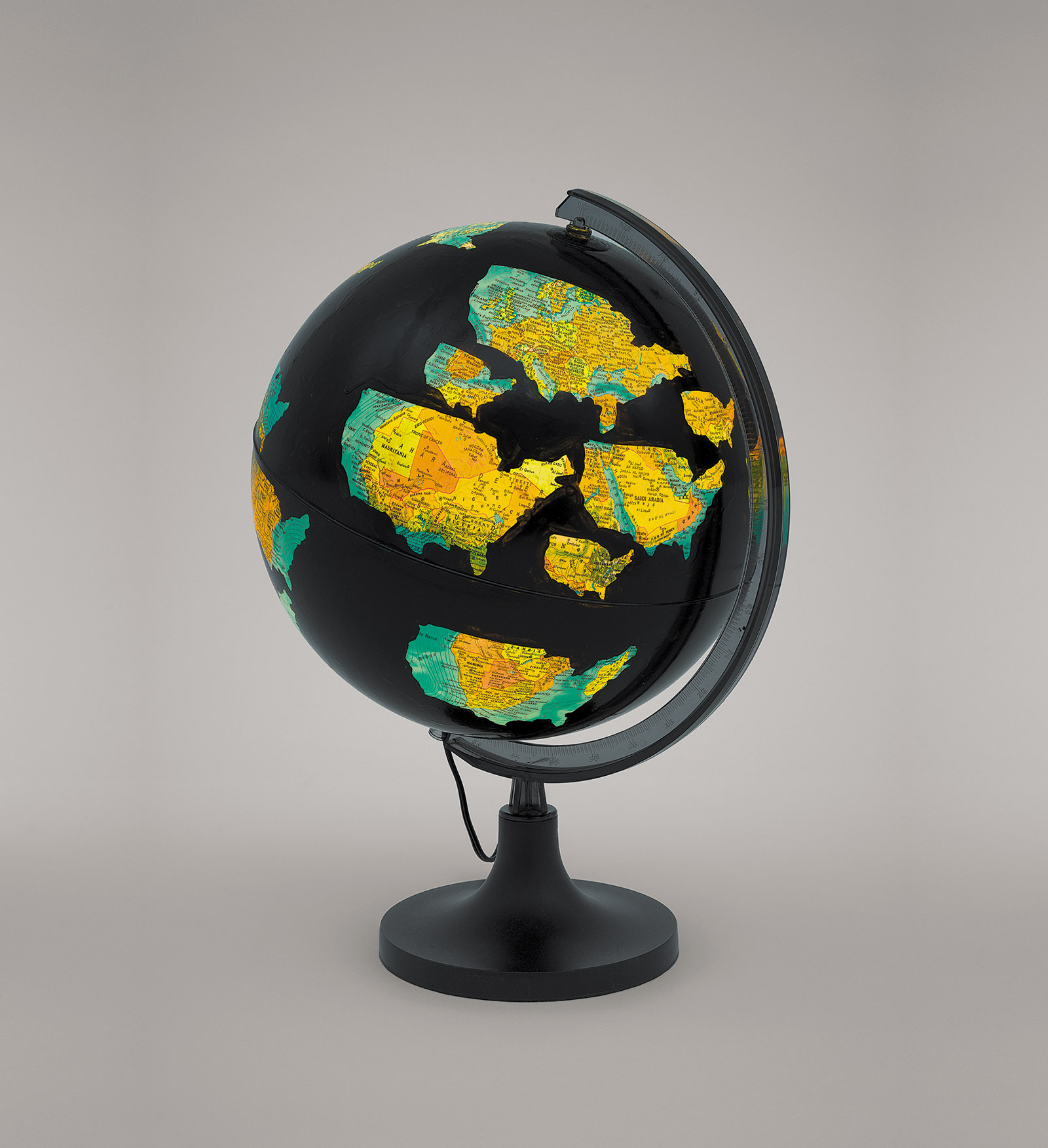

Wojnarowicz was particularly fascinated with maps and used them as backgrounds, as coverings for sculpted heads, as collage elements. A globe, called Science Lesson in 3D (1984), hangs from the ceiling, with miniature toy animals, cars, people, and other objects in turn falling from it, a vivid plea for the fate of the earth. Another globe is illuminated and painted black except for various regions in the shape of the United States, through which shine the familiar borders and place names on the map below (see illustration on page 20). In one such region, Mauritania takes up much of the American Northwest. In another, the Midwest is dominated by Saudi Arabia; in still another, most of the country is the southern tip of Africa. The overall effect is of a dark world dotted by multicolored US-shaped continents—the world literally remade in the United States’ image.

Advertisement

One of the most significant personal influences on Wojnarowicz was the American photographer Peter Hujar, who died of AIDS in 1987. They met in early 1981, were briefly lovers, and remained close friends for the rest of Hujar’s life. The Whitney exhibition features several tender portraits of Wojnarowicz by Hujar, including one that appeared on the cover of The Village Voice in 1983 for a path-breaking essay about the AIDS crisis; three photographs Wojnarowicz took of Hujar’s hand, feet, and head in his hospital room immediately after he died; and numerous paintings devoted to Hujar. Hujar, an established artist when the two met, encouraged Wojnarowicz to pursue the visual arts. Wojnarowicz said that Hujar was “my brother my father my emotional link to the world.”

As more and more of his friends succumbed to AIDS, and as he himself was diagnosed with HIV in 1988, Wojnarowicz began to concentrate more explicitly on the disease and society’s response to it. His essays from the time move easily from the intimate and the personal to the overtly political, building to cries of rage against a government still unwilling to confront the crisis. He began working with ACT-UP and became a prominent AIDS activist.

At this point, perhaps inevitably, Wojnarowicz became a target of the culture wars. In an essay for the catalog of a 1989 New York exhibition that addressed the AIDS crisis, he colorfully castigated the North Carolina Republican senator Jesse Helms and New York cardinal John O’Connor for their antigay policies and pronouncements. (Of the former he wrote, “At least in my ungoverned imagination…I can, in the privacy of my own skull, douse Helms with a bucket of gasoline and set his putrid ass on fire.”) The NEA, fearing backlash in Washington, eventually pulled funding for the catalog.

Shortly thereafter, in Tupelo, Mississippi, Donald Wildmon, head of the fundamentalist American Family Association (AFA), obtained a copy of the catalog of a retrospective of Wojnarowicz’s work at Illinois State University. Wildmon singled out and photographed several images, including gay porn pictures that Wojnarowicz had incorporated into photo-collages called the Sex Series and an image he had painted of Christ shooting up from a larger work called Untitled (Genet after Brassaï). Wildmon put these and other images, stripped from their contexts, into a leaflet titled “Your Tax Dollars Helped to Pay for These Works of Art” and mailed it to every member of Congress, major news outlets, and thousands of religious leaders.

When he saw the AFA mailing, Wojnarowicz contacted the Center for Constitutional Rights, where I was a young lawyer specializing in First Amendment law. He wanted to know if he could sue. With assistance from lawyers at Skadden Arps we sued Wildmon and the AFA for libel and for violating the New York Artists’ Authorship Rights Act, which prohibits misrepresentation of an artist’s work.

The case went to trial in June 1990 in a federal court in downtown New York; the courtroom was packed with Wojnarowicz’s activist and art world friends. Wildmon and the AFA were represented by Benjamin Bull of the Alliance Defense Fund, a nonprofit that supported antigay laws around the world. (It has been rebranded as the Alliance Defending Freedom and most recently represented Masterpiece Cakeshop in the Supreme Court, defending its owner’s refusal to sell a wedding cake to a gay couple. I represented the gay couple in the case.) Wildmon played the country bumpkin at trial. When I, seeking to show that he knew his representation was false, asked him why he took small excerpts from Wojnarowicz’s collages and then falsely presented them as Wojnarowicz’s art, Wildmon replied, “Why, I don’t know the difference between a portrait and a collage.”

We prevailed under the New York Artists’ Authorship Rights Act. The court ordered Wildmon to cease distributing the pamphlets and to send a correction to everyone who had received the initial mailing. We also requested monetary damages, but because Wojnarowicz’s work was rising in value at the time, we weren’t able to show that he had suffered actual economic loss. The judge ordered Wildmon to pay “nominal damages” of one dollar. Wojnarowicz asked for a check, which he planned to incorporate into a future work of art. But by that point, AIDS had overtaken him, and he was unable to do so. The check, along with Wildmon’s pamphlet and a draft declaration from Wojnarowicz featuring his handwritten edits, is on display in the Whitney exhibition.

Advertisement

Some of Wojnarowicz’s most affecting work came at the end of his short life, as he continued to deal with the disease that had consumed his community and would soon consume him. He had begun his career as a writer, but had increasingly turned to the visual arts in the 1980s. Near the end, he married the two, as he incorporated text into his works of art. The Whitney exhibition ends with one such piece, Untitled (One Day This Kid…). It features an innocent image of a young, freckled David, probably taken when he was nine or ten years old. Surrounding the image is the following text:

One day this kid will get larger. One day this kid will come to know something that causes a sensation equivalent to the separation of the earth from its axis. One day this kid will reach a point where he senses a division that isn’t mathematical. One day this kid will feel something stir in his heart and throat and mouth. One day this kid will find something in his mind and body and soul that makes him hungry. One day this kid will do something that causes men who wear the uniforms of priests and rabbis, men who inhabit certain stone buildings, to call for his death. One day politicians will enact legislation against this kid. One day families will give false information to their children and each child will pass that information down generationally to their families and that information will be designed to make existence intolerable for this kid. One day this kid will begin to experience all this activity in his environment and that activity and information will compell [sic] him to commit suicide or submit to danger in hopes of being murdered or submit to silence and invisibility. Or one day this kid will talk. When he begins to talk, men who develop a fear of this kid will attempt to silence him with strangling, fists, prison, suffocation, rape, intimidation, drugging, ropes, guns, laws, menace, roving gangs, bottles, knives, religion, decapitation, and immolation by fire. Doctors will pronounce this kid curable as if his brain were a virus. This kid will lose his constitutional rights against the government’s invasion of his privacy. This kid will be faced with electro-shock, drugs, and conditioning therapies in laboratories tended by psychologists and research scientists. He will be subject to loss of home, civil rights, jobs, and all conceivable freedoms. All this will begin to happen in one or two years when he discovers he desires to place his naked body on the naked body of another boy.

To see this work at the Whitney, where Wojnarowicz, a once peripheral figure, is now celebrated as crucial to the history of American art, in a neighborhood on whose streets he once hustled and whose abandoned buildings have now been transformed into high-rent condominiums, at a time when medicine has found a treatment for HIV/AIDS—though it is still not sufficiently available to all—is to recognize how much the world has changed in a remarkably short period. Marriage equality is a constitutional right, young people are increasingly accepting of a wide range of sexual identities, and the antigay Alliance Defending Freedom is, as its name unintentionally suggests, on the defensive.

But to view Wojnarowicz’s art in the Trump era is also to be reminded of how our culture continues to reject the unconventional, to silence those who challenge settled ways, and to cast out those who decline to conform. Wojnarowicz embraced nonconformity in his art, his life, and his politics. At its best, as in One Day This Kid…, his art implores us to see the innocence in love of all kinds instead of the fear and hatred that it too often prompts. He lived on the margins, but his ability to speak across the divide, honestly and directly, has helped to break through the ignorance that continues to separate us.

This Issue

September 27, 2018

Aquarius Rising

Missing the Dark Satanic Mills

Tenn’s Best Friend