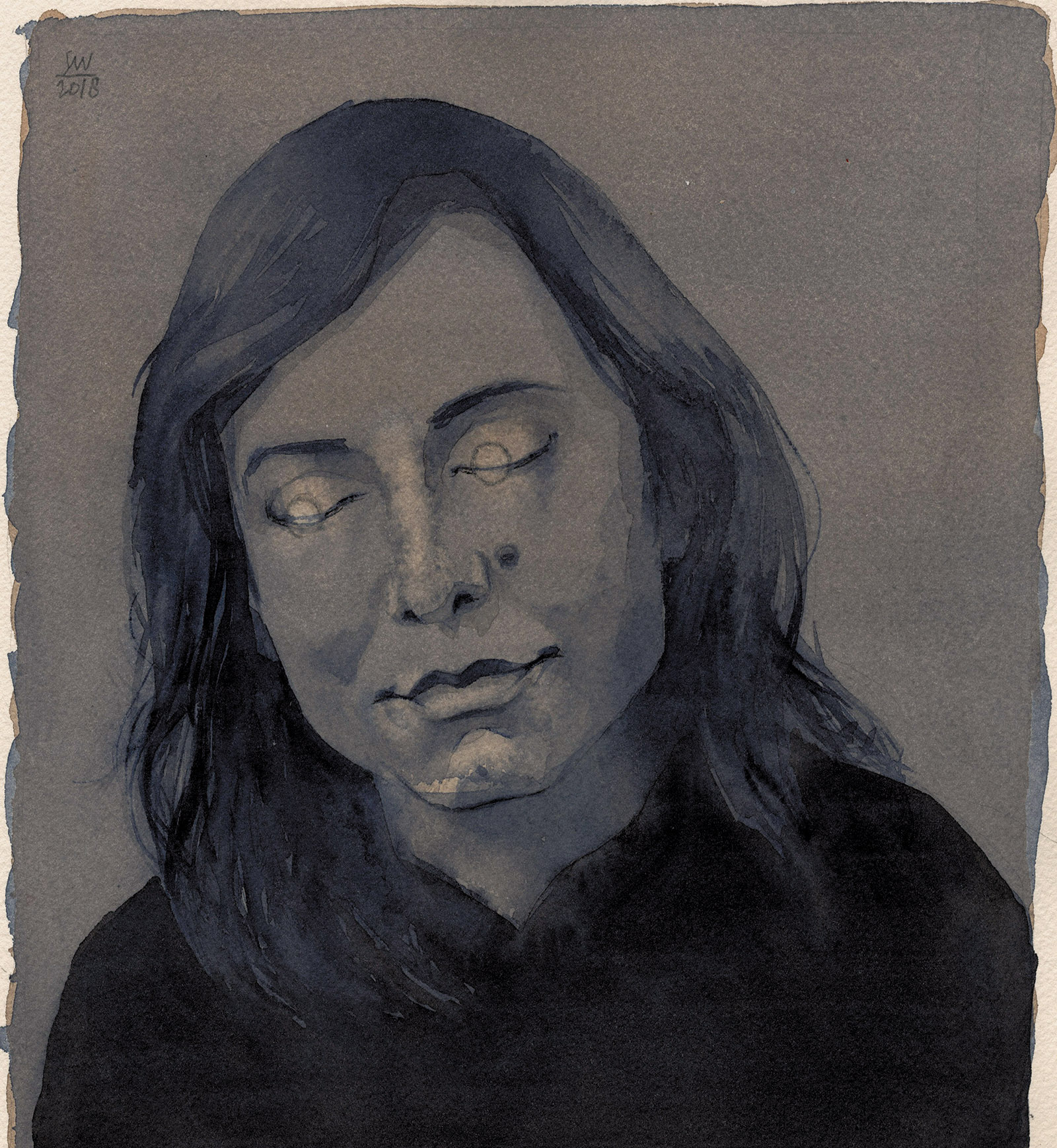

Like her first novel, Eileen (2015), narrated in a memorably dyspeptic first-person female voice, Ottessa Moshfegh’s second novel reads like an uncensored, unapologetic, despairingly funny confession. Its unnamed narrator is a twenty-four-year-old woman who looks “like a model” and defines herself as a “somnophile”: “Oh, sleep. Nothing else could ever bring me such pleasure, such freedom, the power to feel and move and think and imagine, safe from the miseries of my waking consciousness.” In June 2000 she is living in an apartment on East 84th Street, on a trust fund established for her by her recently deceased parents; a Columbia University graduate, she has recently quit a coveted job at a Chelsea art gallery to retreat from the world and indulge herself in prolonged periods of sleep:

[I] took trazodone and Ambien and Nembutal until I fell asleep again. I lost track of time in this way. Days passed. Weeks. A few months went by…. My muscles withered. The sheets on my bed yellowed….

Sleeping, waking, it all collided into one gray, monotonous plane ride through the clouds. I didn’t talk to myself in my head. There wasn’t much to say. This was how I knew the sleep was having an effect: I was growing less and less attached to life. If I kept going, I thought, I’d disappear completely, then reappear in some new form. This was my hope. This was the dream.

Self-medicating—“hibernating”—is the narrator’s stratagem for getting through her life benumbed to feeling: “This was the beauty of sleep—reality detached itself and appeared in my mind as casually as a movie or a dream.”

Since the deaths of her parents, to whom she seems to have been very little attached, the narrator of My Year of Rest and Relaxation has slipped into a state resembling an open-eyed coma. Memories of her childhood and her parents’ dully disastrous marriage torment her; she hopes to avoid memories of their last unhappy days. (Though estranged in life, the father and mother die within a short span of time.) She avoids friends and acquaintances, and barely manages to tolerate her closest friend. She’d wanted a prescription from a doctor just for “downers to drown out my thoughts and judgments, since the constant barrage made it hard not to hate everyone and everything,” but eventually the massive ingestion of drugs dulls more than hatred:

I felt nothing. I could think of feelings, emotions, but I couldn’t bring them up in me. I couldn’t even locate where my emotions came from. My brain? It made no sense. Irritation was what I knew best—a heaviness on my chest, a vibration in my neck like my head was revving up before it would rocket off my body. But that seemed directly tied to my nervous system—a physiological response. Was sadness the same kind of thing? Was joy? Was longing? Was love?

In flat, deadpan, unembellished prose recalling the cadences of Joan Didion and the clear-eyed candor of Mary Gaitskill, Moshfegh portrays the vacuous interior life (she has virtually no exterior life) of a narcissistic personality simultaneously self-loathing and self-displaying. So much critical concentration upon the self is a way of adoring oneself, for the subject is never anything other than the self: “Since adolescence, I’d vacillated between wanting to look like the spoiled WASP that I was and the bum that I felt I was and should have been if I’d had any courage.” Acquiring a glamorous job in a pretentious gallery after graduating from college is easy for her, given her looks, clothing, and style: “I thought that if I did normal things—held down a job, for example—I could starve off the part of me that hated everything.”

If she’d been a man, she thinks, she might have “turned to a life of crime. But I looked like an off-duty model.” Being “pretty” assures her a modicum of social success, but she perceives it also as a trap that allows her to succeed in a world that “valued looks above all else,” which she professes to despise.

As in a fairy tale given a distinctly contemporary Manhattan gloss, the spoiled WASP protagonist decides to withdraw: “I was born into privilege,” she says at one point. “I am not going to squander that.” Allowed the luxury of a withdrawal not available to the lugubrious Eileen, who must live in a filthy hovel with an alcoholic father she has come to hate and work at a job she loathes, the narrator of My Year of Rest and Relaxation systematically prepares for her hibernation by prepaying taxes and bills; her finances are overseen by her deceased father’s financial adviser, who sends her quarterly statements she never reads. Her life is focused on taking drugs to induce sleep, sleeping for as long as she can, waking reluctantly for brief intervals, and returning to sleep as soon as possible. Her fondest memories of childhood are of sharing a bed with her drug addict, alcoholic mother, who crushed Valium into her milk when she was a baby. It is sleep that feels “productive,” for she is convinced that “when I’d slept enough, I’d be okay. I’d be renewed, reborn…. My past life would be but a dream.” Indeed it’s something of a challenge for a novelist to make the achievement of sleep into a goal worthy of hundreds of pages of prose, but Moshfegh succeeds, to a degree:

Advertisement

The speed of time varied, fast or slow, depending on the depth of my sleep…. My favorite days were the ones that barely registered. I’d catch myself not breathing, slumped on the sofa, staring at an eddy of dust…and I’d remember that I was alive for a second, then fade back out. Achieving that state took heavy doses of Seroquel or lithium combined with Xanax, and Ambien or trazodone, and I didn’t want to overuse those prescriptions. There was a fine mathematics for how to mete out sedation.

Readers with a particular interest in designer drugs will thrill to the eroticism of Moshfegh’s litanies:

My Ambien, my Rozerem, my Ativan, my Xanax, my trazodone, my lithium. Seroquel, Lunesta. Valium. I laughed. I teared up…. I counted out three lithium, two Ativan, five Ambien. That sounded like a nice mélange, a luxurious free fall into velvet blackness. And a couple of trazodone because trazodone weighed down the Ambien…. And maybe one more Ativan.

The narrator tells herself that what she is doing is not suicide but rather the opposite of suicide: “My hibernation was self-preservational. I thought that it was going to save my life.” The major side effects from the drugs appear to be merely comical: not cardiac or liver failure as one might expect, not brain damage, not even severe constipation, but rather sleepwalking, sleeptalking, sleep-online-chatting, sleepeating, sleepshopping, sleepsmoking, sleeptexting, sleeptelephoning, and sleepordering Chinese food. In passing the narrator alludes breezily to weight loss, imbalance, and atrophied muscles, but only in passing, and the point is made that she never loses her looks. When she takes her blood pressure in a drugstore she notes indifferently that it is 80/50—“That seemed appropriate.”

When, from time to time, despite ingesting enough medication to kill an elephant, the narrator still can’t sleep, she compulsively watches movies she has seen before, which help to narcotize her mind: “The movies I cycled through the most were The Fugitive, Frantic, Jumpin’ Jack Flash, and Burglar. I loved Harrison Ford and Whoopi Goldberg.” Even movies for which she feels contempt are cherished: “The stupider the movie, the less my mind had to work.”

My Year of Rest and Relaxation is laced with blackly comic interludes. Though passive to the point of virtual catatonia, the narrator can’t avoid interacting with a very few other people who include a “lover” named Trevor of such astounding sexist oafishness he might have stepped out of one of the more fatuous episodes of Sex and the City: “I interpreted Trevor’s sadism as a satire of actual sadism.” Even funnier than Trevor is a radiantly nutty therapist named Tuttle who prescribes drugs extravagantly, promiscuously, and unquestioningly, prattling away in a unique psychobabble:

Dr. Tuttle had warned me of “extended nightmares” and “clock-true mind trips,” “paralysis of the imagination,” “perceived space-time anomalies,” “dreams that feel like forays across the multiverse,” and “trips to ulterior dimensions.”… And she had said that a small percentage of people taking the kind of medications she prescribed for me reported having hallucinations during their waking hours. “They’re mostly pleasant visions, ethereal spirits, celestial light patterns, angels, friendly ghosts. Sprites. Nymphs. Glitter.”

In flashbacks the narrator recalls her indifferent mother, who “got away with so much because she was beautiful,” a caricature of a narcissist who expresses surprised disapproval when her husband, dying of cancer, requests to be brought home to die, and whose “only intellectual exercise…was doing crossword puzzles.” (“She looked like Lee Miller if Lee Miller had been a bedroom drunk.”) More stereotypical are satiric portraits of art gallery proprietors, patrons, and artists: “The art at Ducat was supposed to be subversive, irreverent, shocking, but was all just canned counterculture crap, ‘punk, but with money.’” The gallery’s star artist is Ping Xi, whose early hugely successful work is “splatter paintings, à la Jackson Pollock, made from his own ejaculate.” (Critics rave: “Here is a spoiled brat taking the piss out of the establishment. Some are hailing him as the next Marcel Duchamp. But is he worth the stink?” When a homeless person takes up residence in the gallery, patrons assume that she is part of the exhibit.

Advertisement

As the year of rest and relaxation progresses, slowly and haltingly, it begins to seem likely that the somnophile is in fact deeply aggrieved, mired in the kind of pathological grief to which Freud gave the romantic label “melancholia,” to distinguish it from the less extreme, more commonly experienced “mourning.” Her drug-taking is a means of escaping from “the tragedy of my past”; she cannot express mourning, it seems, perhaps because she had not loved her parents, and so she is trapped in melancholia—a paralysis of the spirit. Yet My Year of Rest and Relaxation is most convincing as an urbane dark comedy, sharp-eyed satire leavened by passages of morbid sobriety, as in a perverse fusion of Sex and the City and Requiem for a Dream.

Both Moshfegh’s novels, like the majority of the deftly narrated, deadpan short stories collected in Homesick for Another World (2017), showcase characters who are defiantly unlikable—ungenerous, unfriendly, critical of others, lacking intellectual or cultural interests. They are “outspoken”—if female, the very opposite of “feminine.” Cripplingly self-conscious, embittered and spiteful, the antiheroine of Eileen acknowledges that she “hated almost everything. I was very unhappy and angry all the time.”

Like the narrator of My Year of Rest and Relaxation, Eileen shares a bed with her mother even as her mother is dying, and wakes in the morning beside her corpse: “She died when I was just nineteen, thin as a rail by then, something my mother had praised me for.” To immunize herself from the “misery and shame” that surround her, she has learned to face the world with a “death mask” appropriated from reproductions of actual death masks. Eileen’s angry stoicism masks her self-pity, though the reader is likely to sense that the energy galvanizing the novel has been, indeed, an infinite pity for the misfit self abandoned by an unfeeling mother.

As the somnophile had predicted, My Year of Rest and Relaxation concludes on a hopeful note. After nearly a year she begins to free herself from her enchantment with sleep. She takes the last of her pills; she ventures outside. She begins to rediscover the world. She shakes off her past identity: “I had no dreams. I was like a newborn animal. I rose with the sun.” And lest we should miss the point: “That was it. I was free.”

More engaging than Eileen, more varied in tone, and much funnier, My Year of Rest and Relaxation is a recycling of the materials of Eileen that tracks a disagreeable, self-absorbed young woman in her twenties through a cathartic experience that leaves her ostensibly altered and prepared for a new, freer life. Where Eileen ends abruptly and not very convincingly, after an awkward melodramatic interlude, My Year of Rest and Relaxation ends with the spectacle of the September 11, 2001, terrorist attack on the World Trade Center, for which the author has subtly prepared us. In fact, it seems likely that the narrator’s college roommate—about whom she has felt a prevailing exasperated boredom—has died in the attack. Unambiguously now, the somnophile has been awakened. “My sleep had worked. I was soft and calm and felt things. This was good. This was my life now…. I could move on.”