The work of a photographer cannot help but be autobiographical. Every image produced has been seen by the photographer’s eye and transmitted, by way of the photographer’s hand, to the film, plate, or digital apparatus that is the prosthesis of memory. But some work is more personal than other work. The act of witness performed by a photojournalist, who aims for clarity and compression, is different from that of the street photographer, who engages in a more subjective way of seeing. And both of those differ considerably from the task of photographers who are out to record the circumstances of their own intimate lives. The history of the medium is sparsely dotted with these: photographers who documented their childhood (Jacques-Henri Lartigue), youth (Nan Goldin, Larry Clark), parenthood (Nicholas Nixon), middle age with aging parents (Mitch Epstein, Larry Sultan), and even their own physical decline (Hannah Wilke, John Coplans). Generally, the autobiographical impulse is confined to an episode in a career otherwise devoted to other matters. There are not many photographers who, like Sally Mann, have made their life and the circumstances surrounding it the central focus of their work.

But that is not to say that Mann’s work is a diary or a chronicle or a succession of mirrors. Her scope is concentric, in widening rings, beginning with her nuclear family and extending outward to the land they inhabit, the region surrounding it, the larger territory surrounding that, and the long, tangled, bitter, complicated history that underlies all of it. Those elements are not distinct from one another, but intermingled: the small-scale with the large, the actual with the forgotten, the intimate with the geopolitical, the twenty-first century with the nineteenth, the living with the dead, portraits with landscapes. Her earlier books and shows generally focused on one or two of these, but the connections have become more visible with every succeeding project, in particular her memoir, Hold Still (2015). The current survey exhibition of her work, “Sally Mann: A Thousand Crossings,” organized by the National Gallery of Art and the Peabody Essex Museum, makes their continuity inescapable, blending them together in streams running from room to room and chapter to chapter to form a river.

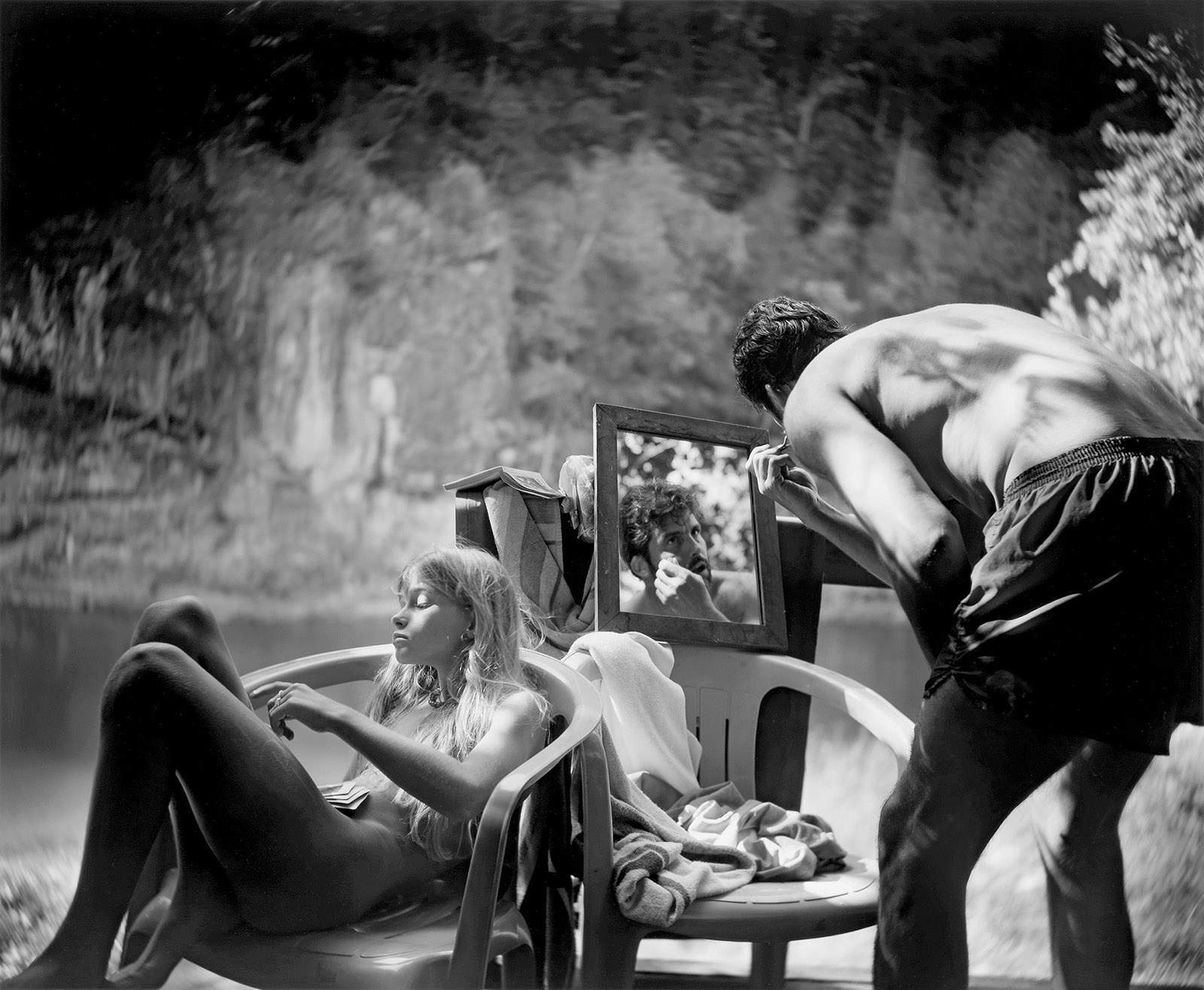

That metaphor is not idly chosen. As the title suggests, many rivers figure in her photographs, above all the Maury, which runs by her family’s farm in Lexington, Virginia, and becomes almost a character in the pictures she took of her children growing up. Those pictures, collected in Immediate Family (1992), were what brought her work to the attention of the wider world. Mann photographed her children, Emmett, Jessie, and Virginia, when their ages were in the single digits, in an endless summer idyll in the privacy of the protective curving banks of the Maury, wearing few or no clothes and frequently smeared with mud or berry juice.

The pictures are a prelapsarian dream of innocence, but she had the bad luck to publish the book just as the nation was experiencing a moral panic concerning child pornography, coming on the heels of the repressed-memory craze. Suddenly the depiction of naked children, a staple of sentimental imagery since the Victorian era, was viewed by many with alarm. Furthermore, Mann had not made her pictures sufficiently sentimental. There are cuts and bruises, a dirty sheet, a candy cigarette, a dead deer, skinned squirrels, sundry other intimations of mortality, and frequent sly jokes, such as the inflatable toy alligator that seems to be creeping up on a sleeping Virginia, age three.

Her photographs were deemed “disturbing” on the cover of The New York Times Magazine; a writer for The Wall Street Journal used a photograph from the series, which had received no government funding, as Exhibit A in a screed against government funding for the arts (and the piece was illustrated with that photograph of a nude Virginia, there disfigured with black bars across her eyes, chest, and groin); and Mann received piles of mail, some supportive, some vituperative, and some psychotic. The controversy unquestionably established Mann’s name, but at a steep emotional cost. By the time it erupted, however, the children were already becoming too grown for innocent playacting in front of the lens, and Mann had gone literally to ground. As she wrote to a friend in 1994, “there’s something strange happening in the family pictures. The kids seem to be disappearing from the image, receding into the landscape.” She was beginning to photograph the landscapes in Virginia and later Georgia that were to comprise the series that, when it was completed in 1996, was called “Mother Land.”

The pictures are overpoweringly lush and fecund, visibly humid, variously scarred by moisture and damaged lenses, the contrasts sometimes extreme, the sun burning through and seeming to consume the leaves on the trees or eat away at the preposterous ruined colonnade of what was once an antebellum mansion. It’s no wonder that Hilton Als thought that she was “too obsessed with the South’s picture-postcard ‘terrible beauty’” and that she wanted to be “a mythologizer, a Faulkner of the lens,” but on the other hand the pictures are authentically out of time, existing somewhere between the nineteenth century and the eve of the twenty-first in a loop of creation and destruction. And for all that Mann is in some ways a very literary photographer (and an excellent writer herself), her immediate inspiration was not Faulkner but the nineteenth-century photographer Michael Miley, whose 7,500 glass-plate negatives she found in an attic at Washington and Lee University in 1973.

Advertisement

She spent more than two years cleaning the plates, then printed over a thousand of them. Miley was a hard-working all-around photographer in the mold of his time who began taking pictures during the Civil War, made a living as a portraitist and a documentarian for educational institutions, and experimented on his own. Among the local sights he had photographed was the very bend on the Maury that Mann was to extensively shoot more than a century later in Immediate Family. His work was a panoply of revelations, exhibiting a lyrical plainspokenness, introducing her to the beauty of the collodion process, embodying the passage of time, and establishing artistic roots for her right in the place where she had lived nearly all her life. Mann felt a deep connection to the topography of central Virginia, but her parents had come from Texas and Boston and were liberal intellectuals inclined toward eccentricity. Having Miley as her elective ancestor helped guide her into the folkways and inner life of the place.

Her next project, with seeming inevitability, concerned Civil War battlefields, sites of some of the most brutal clashes: Antietam, Manassas, Fredericksburg, Cold Harbor, the Wilderness. She was beginning to learn the exacting wet-plate collodion process and to use antique cameras and weathered lenses. That might, on the face of it, sound a bit like her version of Civil War reenactment, although the dark, brooding photographs she produced look little like the pictures of Alexander Gardner or Timothy O’Sullivan. Some of them barely look like photographs at all. Her Battlefields, Antietam (Black Sun) (2001) shows one narrow band of identifiable landscape—a zigzagging split-rail fence—while the ground leading up to it is murk and the smeared sky might appear to contain two or even three orbs. The titular one, risen halfway up from the horizon, is very nearly the darkest thing in the picture. The whole thing suggests a drypoint etching by Odilon Redon or a spit-and-soot composition by Victor Hugo. The pictures flaunt their ostensible imperfections: pocked and scratched surfaces, waves and billows of fluid, peeling emulsion, large areas of impenetrable darkness. They convey accrued time and the overwhelming presence of death, forcefully declaring that nothing has been laid to rest.

Of course, coming to terms with the South meant that Mann had to confront the subject of race. In the flow of the galleries of “A Thousand Crossings,” what succeeds the Civil War pictures are two large frames containing assemblages of snapshots and other documents concerning Virginia “Gee-Gee” Carter, who raised Mann. As Mann writes:

Down here, you can’t throw a dead cat without hitting an older, well-off white person raised by a black woman, and every damn one of them will earnestly insist that a reciprocal and equal form of love was exchanged between them…. Could the feelings exchanged between two individuals so hypocritically divided ever have been honest, untainted by guilt or resentment?

Gee-Gee had six children, was widowed young, put all her children through college, and worked for Mann’s family six days a week for nearly fifty years, raising not only Mann and her brothers but also Mann’s own children, the youngest of whom was named after her. She appears, full-face and smiling, in the early pages of Immediate Family, and afterward as a gnarled guiding hand, a benevolent silhouette, a head of fine white hair watching over a sleeping child. In other pictures by Mann she is defined by her feet, large and rooted. She was unquestionably Mann’s deepest connection to the land.

Pursuing this idea, the photos Mann took of Gee-Gee are mixed with the series called “Abide With Me” (2008–2016), devoted to African-American churches in the Virginia countryside, while “Blackwater” (2008–2012), a study of Virginia’s Great Dismal Swamp in large-format tintypes, is blended with “Men” (2006–2015), a succession of posed portraits of young African-American males. Some of the churches are active and some long abandoned; they are uniformly low, peak-roofed, white clapboard. Unlike Walker Evans’s churches they are not presented head-on like so many mugshots, but discreetly, at an angle or from the side, most of them wrapped in trees or vines. Aside from the abandoned ones they are well tended and impossible to date. They might have been built last year or a century ago. They all appear peaceful, home-like refuges for their congregations.

Advertisement

The swamp views are ghostly. At least one (Blackwater 18) hints at Edward Steichen’s epochal The Pond—Moonrise (1904) (a Pictorialist influence has always been evident in Mann’s work), but many of the others, so dark that the areas of light can look like effects of solarization, suggest something even more sinister than her Civil War pictures, if only by virtue of being concealed. (In view of the difficulties of transporting and deploying a giant period camera in the swamp, the pictures were taken digitally, printed, and then rephotographed as tintypes.) Views of water and vegetation lacking any evident human trace, they carry on from some of the pictures she took in the late 1990s for Deep South (2005), a continuation of the “Mother Land” series into Mississippi, in particular the one that shows the muddy, featureless site on the Tallahatchie River where Emmett Till’s body, attached to a fan blade by barbed wire, was sunk by his murderers in 1955.

The connection is underscored by the pictures’ alternation with those of “Men.” The men, paid models, are shown in poses and attitudes—lying on a bare bench; interlaced fingers against a bare chest; outlined in stark profile—that inescapably suggest images of slavery, a notion enhanced by the aging and distancing effects of the collodion process. Over the past twenty years Mann has often seemed to use her camera as a means for reaching back into the past; here it is as if she is searching hopelessly for a way to set things right in retrospect.

The “Men” pictures have another point, however, which is pursuant to her career-long interest in the eloquence of the human body, a matter first explored at length in her book At Twelve: Portraits of Young Women (1988). There the subjects, all of them twelve years old, are each portrayed in a different way, with props and settings specific to them, and they each assume poses that propose themselves as signatures. She went on to study her children’s bodies, her father’s body near and after death—there do not seem to be any photos of her mother—and Gee-Gee’s body, but black men’s bodies had been lacking, a gap in her understanding. She briefly returned to photographing her children in a 2003 series, “What Remains,” which concentrates the center of each of their faces on a plate, each printed very large: about 48 1/2” x 38 3/4”—a series that has gained additional poignancy since the untimely death of Emmett in 2016. The title and framing suggest, even more than her other pictures of them, an attempt to fix them forever in memory.

Her husband, Larry, appears discreetly on the edges of the family pictures, but generally is more often evoked, thanked, paid homage to than seen. There is one grand picture of him, The Turn (2005), showing him turning his body a quarter to the left as he walks through a vast expanse of mist-covered meadow—but he is seen from the back. A few years earlier, however, he had been afflicted by late-onset muscular dystrophy, and in 2003 she began recording its effects in an ongoing series called “Proud Flesh.” There the distancing effect of the collodion process allows a subject of nearly unbearable intimacy and vulnerability, one that could make the viewer feel like an intruder or worse, to be lyrically alluded to without the sort of brutal confrontation that photography might otherwise involve.

“A Thousand Crossings” and its catalog represent a large portion of Mann’s multifaceted oeuvre. It is by turns tender, light-hearted, sun-dappled, epic, allusive, burdened, scarred, mournful, dark, mindful, exploratory, expiatory, commemorative, introspective, conciliatory, and wise. The aspect of her work they slight is death. This might seem an absurd claim in view of how largely death looms in the battlefield series and “Blackwater,” but those are allusions and not the thing itself, which is the primary subject of her book What Remains (2003). That begins with the death of a beloved greyhound, Eva, and Mann’s consequent decision to preserve her hide and her bones, which she photographs as if they were vestiges of great antiquity. (It should be noted not only that Mann’s father possessed a large collection of death-related artifacts from around the world, but also that until fairly recently the crudely taxidermized remains of Robert E. Lee’s and Stonewall Jackson’s horses were both on display in Lexington, at different institutions.)

Further on in What Remains, which also includes a selection of Civil War battlefields in addition to the large close-ups of her children’s faces, can be seen a series that began as an assignment from The New York Times Magazine: to photograph the University of Tennessee’s Forensic Anthropology Center, otherwise known as the Body Farm. There the cadavers of persons who have willed them to science are allowed to decay in the open, so that the process can be studied by forensic anthropologists. Their condition ranges from nearly intact to mostly skeletonized, but Mann’s process emphasizes not their insalubriousness but their return to and oneness with nature, as they appear to dissolve into the fallen leaves of the autumnal landscape. I am not faulting Mann or her collaborators for omitting these pictures in “A Thousand Crossings”; there are several understandable reasons. But they are nevertheless an obvious missing piece in this grand panorama of her art and her worldview.