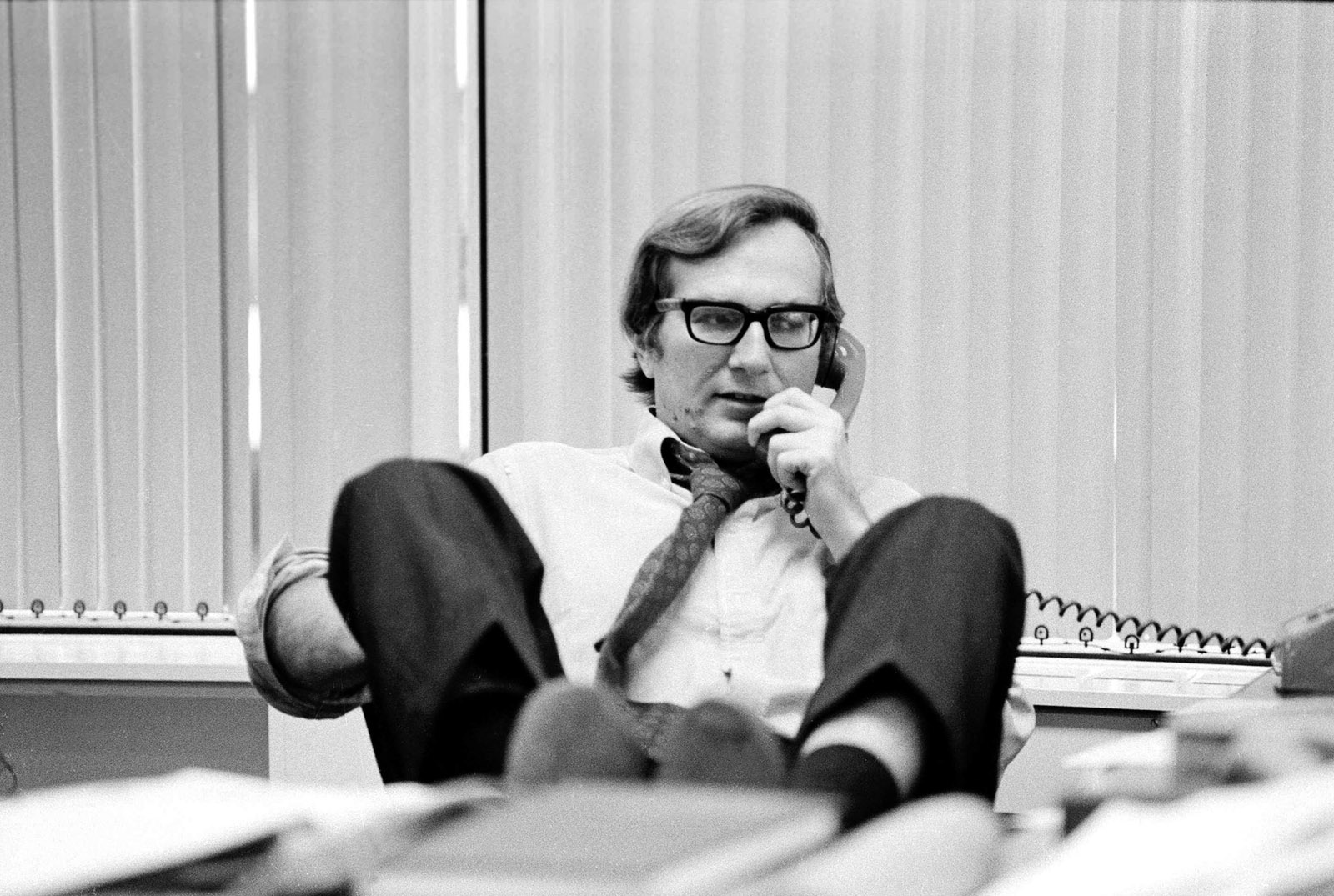

Seymour Hersh has been the premier American investigative reporter of the last half-century. In the late 1960s his articles (some of which appeared in these pages) helped inspire a partly successful campaign to abolish America’s arsenal of chemical and biological weapons. His 1969 exposé of the My Lai massacre, based on an interview with the man who ordered it, Lieutenant William Calley, revealed the savagery of the Vietnam War. He provided the first comprehensive account of President Richard Nixon’s secret bombing of Cambodia. His disclosure in 1974 that the CIA had spied on antiwar activists prompted the creation of two congressional investigating committees. He led the effort to unearth American dirty tricks in the early 1970s against Chile’s democratic socialist president, Salvador Allende. After September 11, he warned that US intelligence was being manipulated to justify an invasion of Iraq, and in 2004 he brought to light the abuses at the Abu Ghraib prison.

Hersh has also been dogged by criticism, some of it legitimate. He has bullied sources, lashed out at colleagues, succumbed to hoaxes, and destroyed the reputation of at least one blameless person: Edward M. Korry, the US ambassador to Chile between 1967 and 1971.

In 1974 Hersh reported in The New York Times that Korry had facilitated the CIA’s efforts to foment internal opposition to Allende, who committed suicide during a coup that overthrew him in 1973. In fact, the White House and the CIA had bypassed Korry. After Hersh published his story, the ambassador loudly proclaimed his innocence. According to Korry’s wife, Patricia, Hersh then tried to essentially blackmail her husband, offering to clear his name in return for his assistance in implicating Henry Kissinger, whom Hersh despised. In 1981 Hersh apologized to Korry in a long, highly unusual, page-one correction in the Times, after which Hersh admitted to Time magazine, “I led the way in trashing him.”

Now eighty-two, Hersh has told his own story. At its best, Reporter is a lively self-portrait of a maverick and troublemaker. But it is scrubbed and sanitized. He appears in a half-light; the book does not illuminate the darkest corners of his long career. In an interview with Kissinger in the early 1970s, Hersh told him, “The only spirit is truth.” But Hersh is less than truthful in chronicling, for instance, the Korry affair, about which Reporter contains two hasty, misleading paragraphs that ignore the damage he inflicted. (Hersh insists that he was “very surprised” to learn in 1980 that Korry “had not been trusted by the CIA station chief” in Chile.) For a full view of Hersh and an authoritative sense of his career, which embodies the expansive possibilities of muckraking as well as its many perils, one must look elsewhere.

Hersh’s Yiddish-speaking father, Isadore, was, in his son’s words, a “man of mystery” from Lithuania, who died when Seymour was seventeen; his mother was born in Poland. Six decades later, Hersh discovered that his father’s farming village, near Vilnius, was devastated by a German Einsatzgruppe during World War II: 664 Jews were executed in August 1941. After his father’s death, Hersh was told by a family friend from the local synagogue to “fuck them before they fuck you!”

He took over the family business, a dry cleaning store located in what he calls a “black ghetto” on Chicago’s South Side. He was a lackluster student: after being kicked out of the University of Chicago Law School at twenty-two, he worked at Walgreens. But he soon stumbled into a job at the City News Bureau, an outfit that supplied information, mainly about crime and sports, to Chicago’s thriving dailies. With its tobacco haze and cynical scribes, the bureau evoked Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur’s The Front Page. It was here that Hersh began to acquire his moral education: “the cops were on the take, and the mob ran the city.”

In Seymour Hersh: Scoop Artist (2013), his comprehensive, largely admiring biography, the journalism professor Robert Miraldi suggested that Hersh developed some bad habits in Chicago. A City News Bureau veteran told Miraldi that “in the end, whatever went into a story was accurate, but the methods might not have been ethical.” Bureau reporters would pose as cops or coroners to coax information from unwitting citizens. “Those tactics,” wrote Miraldi, “seem remarkably similar to what Hersh used in finding Lieutenant William Calley a decade later.”

After six months in the army and a stint in Pierre, South Dakota, for United Press International, Hersh returned to Chicago for a position at the Associated Press and began to closely follow the news from Vietnam; the reports he most admired were those by David Halberstam, Charles Mohr, and the fiercely independent Washington-based I.F. Stone. In 1966 Hersh became the Pentagon correspondent of the AP. He was immediately dismayed by the lethargic, pipe-smoking journalists who worked alongside him. The Vietnam War was raging, but the Pentagon press room was “stunningly sedate.” Hersh began to wander the halls, chatting up officers in the cafeteria and showing undisguised contempt at press briefings. In Reporter, he describes one such session: “When the officer finished his presentation and asked for questions, I stood up and, invoking my right as the senior AP correspondent, thanked him for his time and walked out.”

Advertisement

Officers leaked him information that left him “frightened” by the lies he was being told about Vietnam. For decades he stayed in touch with those military sources, from whom he learned that there are “many officers, including generals and admirals, who understood that the oath of office they took was a commitment to uphold and defend the Constitution and not the President.”

A merit of Reporter is the way in which it divulges Hersh’s trade secrets: Be a bookworm (“read before you write”); work the graveyard shift (late one evening in 1967, he allowed Stone to slip in and ransack the AP’s files); scrutinize the retirement notices of government and military officials (some of them will sing); be alert when meeting sources in restaurants (they may leave secret manila envelopes on chairs); behave as though journalism is a bazaar (when CIA Director William Colby asked Hersh in 1973 not to publish a story, “I told him I would do what he wished, but I needed something on Watergate and the CIA in return”); and, lastly, assume your job is precarious (“Investigative reporters wear out their welcome…. Editors get tired of difficult stories and difficult reporters”).

What is Hersh’s underlying philosophy and motivation? On this question, Reporter, which is written in chatty, hurried, self-satisfied prose, is not very introspective or revealing. Ida Tarbell’s father was ruined by Standard Oil, which motivated her to write her classic work exposing the company’s transgressions. Stone was a left-wing intellectual. Hersh’s politics, by contrast, are rather inchoate. When I was researching a profile of him for the Columbia Journalism Review in 2003, Mark Danner told me that “if he has an ideology, it’s the belief that the government should not be able to tell a story publicly that is really a contradiction of what’s going on in reality. And he sees his job as closing the gap between the public version and real version.”

In the case of Vietnam, that gap was vast. In 1969 Hersh received a tip that a soldier had been court-martialed for directing a massacre in Quang Ngai province. It was up to Hersh to learn the soldier’s name and locate him. He has related this tale many times before, in speeches and interviews, but it is worth having in a book: it’s a classic account of journalistic ingenuity, indefatigability, and trickery. While hunting for Calley at Fort Benning, Georgia, an army base “roughly as big as all of New York City,” Hersh, dressed in business attire and carrying a briefcase, told suspicious soldiers that Calley’s lawyer believed he was “guilty of nothing”; Hersh later insisted that remarks like that were merely “the standard newspaperman’s bluffing operation”—as if every reporter behaves that way. After he interviewed Calley, Hersh traveled the US in search of other witnesses, eventually alighting on Private Paul Meadlo, whose foot was blown off the morning after the My Lai massacre. Hersh found him on a chicken farm in Indiana. “I began my talk with Paul,” Hersh writes, “by asking to see his stump.”

Hersh was a shrewd businessman as well as a gifted sleuth. He and his collaborator, David Obst of the Dispatch News Service, were then syndicating the five My Lai stories to newspapers, but they were determined to see the exposé on television as well. What ensued is obscured in Reporter. In Miraldi’s words, Meadlo “allowed Hersh and Obst to be his agents, to market him for interviews.” The private told his harrowing story to CBS, which paid Hersh and Obst $10,000. Meadlo received nothing except a free trip to New York City for the CBS broadcast. In Reporter, Hersh insists that it would have been “completely unethical,” under the canons of journalism, to have paid Meadlo. But at other points in his career Hersh has expressed regret over this episode. In Miraldi’s biography, the following quotes are attributed to Hersh: “I don’t claim this as the greatest day in my professional life…. We sold Paul Meadlo, in effect.”

The My Lai story earned Hersh a Pulitzer Prize in 1970 and the recognition he craved. Random House wanted a book, which became My Lai 4, from whose newspaper syndication rights alone he earned $40,000. He began to lecture on campuses, galvanizing students with blistering vignettes of the My Lai carnage, and has continued to give lucrative speeches ever since.

Advertisement

Hersh’s aspiration had long been to work for The New York Times, and he arrived in its Washington bureau in 1972. It wasn’t a logical destination: the Times had no tradition of muckraking. But The Washington Post was beating it to the story of the Watergate scandal, and the Times’s executive editor, A.M. “Abe” Rosenthal, needed a master reporter to match Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein. Hersh, who called himself a “Vietnam junkie” and was spending most of his time on the American machinations in Southeast Asia, was ordered to devote his energy to Watergate. He resisted, fearing that Woodward and Bernstein were “too conversant with White House officials whose names I didn’t even know.” But he was a quick study and, in 1973, produced more than forty articles on Watergate. Still, he couldn’t catch up with Woodward and Bernstein. Hersh once visited a source and found a sly note left behind by Woodward: “Kilroy was here.”

In December 1974 Hersh broke what he calls the “most explosive” story that he would do for the Times, about the CIA’s domestic spying. Regarding his sources, Hersh writes, “I can name one of them now—Bob Kiley, who died at the age of eighty in August 2016 of Alzheimer’s disease.” Kiley worked for the CIA from 1963 until 1970, during which time he infiltrated student groups. After resigning from the CIA, Kiley helped administer the Boston and New York mass transit systems. When he died, Hersh spoke at his memorial service in New York.

The story burnished Hersh’s fame, and when Leonard Downie Jr. published The New Muckrakers in 1976, naturally there was a chapter on Hersh, who groused that All the President’s Men was “still number one” on the best-seller lists. “I keep thinking of all the money Woodward and Bernstein got,” Hersh told Downie. “But then that’s what helped to create the mystique about investigative reporting. I can’t really complain. It’s put money in my pocket, too.” In a long, fascinating interview with Rolling Stone in 1975, Hersh alluded to the film version of All the President’s Men and proclaimed that “having Robert Redford play me wouldn’t bother me at all.” There has never been a film about Hersh’s journalistic adventures, but he profited nevertheless, getting ever higher fees for his speeches.

In 1975 his wife, Elizabeth, enrolled in medical school in New York, and Hersh, a creature of Washington, found himself in the West 43rd Street newsroom of the Times. With Jeff Gerth, he spent six months (and $30,000) investigating the reputed mobster Sidney Korshak. Times executives feared a libel suit, and Hersh complained bitterly that the story was pruned by “ambitious deputy editors eager to show Abe [Rosenthal] that they could make a Hersh series sing.” Those tensions (amid his “disgust at the editorial mischief”) prompted him to throw a typewriter through the window of his office.

Hersh and Gerth soon launched a probe of Gulf and Western, one of the country’s largest conglomerates. To some degree, it was uncharted terrain: muckraking in the late 1960s and 1970s was generally directed at the government, not formidable corporations. For the first time, Hersh tasted his own medicine: G&W executives treated him with contempt and recorded his phone calls, during which he reportedly said such things as “You better see me. Otherwise, you are going to jail with the others” and “G&W is a piece of shit—garbage.” In Reporter, Hersh denies those remarks but does admit to making some “deservedly tough” calls to G&W executives. Once again, the story was stringently handled by “an ass-kissing coterie of moronic editors.” (Both the Korshak and G&W exposés received mixed responses from readers and press critics.)

Vietnam and Watergate had receded; the press was becoming more restrained and centrist; by 1979, it was time for Hersh to move on. Editors at the Times were uneasy about his use of anonymous sources and his aggressive tactics for getting information. Hersh contends that he didn’t abuse sources on the telephone, but one of his editors at the Times, Robert Phelps, told me incredulously sixteen years ago that “he would call people and he’d say, ‘I’m Seymour Hersh, I’m doing a story on this…If he doesn’t call me, I will get his ass.’ They’d call back.” “His ability to make people cower on the phone was unbelievable,” the influential Times editor Arthur Gelb remembered in 2011. Woodward has said that Hersh’s reporting techniques at The New York Times in the 1970s would not have been condoned at The Washington Post.

Hersh spent the next four years chasing an old enemy, Kissinger, about whom he later remarked, “When the rest of us can’t sleep we count sheep, and this guy has to count burned and maimed Cambodian and Vietnamese babies.” The result, in 1983, was The Price of Power: Kissinger in the Nixon White House, which contained chapters on Vietnam, Cambodia, Chile, and Bangladesh, among others. Based on a thousand interviews, it is Hersh’s best book, respected by historians. It also forced Hersh to confront some errors in his earlier newspaper reporting, especially his mistreatment of Ambassador Korry. Only one reporter, Joseph Trento of the Delaware News Journal, pursued the Korry matter in the 1970s, and Hersh did not appreciate his scrutiny. “You have no business reporting on this story,” he told Trento. “You should turn your sources over to me…I work for the New York Times, this is our story.” But Hersh also told him that Korry “was the only schmuck dumb enough to tell the truth.”

When Hersh started to research his book on Kissinger, however, he realized that he needed the ambassador’s help. An old friend of Korry’s, Richard Witkin, who spent thirty-five years on the staff of the Times, told me for my CJR report that “Hersh had no way of getting the documentation that he wanted [on Chile]. And so he finally went up to Korry’s house. And Ed said, ‘You want the documents, you can have the documents. But only if you get a front-page retraction printed in the New York Times.’” Rosenthal, who was a friend of Korry’s, complied. But the apology may have come too late: the affair took a heavy toll on Edward and Patricia Korry, and they eventually moved to Switzerland. Miraldi covered the episode scrupulously in his biography and concluded that, the apology notwithstanding, “Hersh did not believe Korry, plain and simple.” Korry died in 2003.

The vitality in Reporter fades as the Reagan years approach. There were more books—on the downing of Korean Air Lines Flight 007 by the Soviets in 1983; on Israel’s acquisition of nuclear weapons, a project of daunting complexity—but they didn’t fly off the shelves. Woodward, meanwhile, was producing a stream of best sellers (which were criticized for their reliance on high-level, anonymous sources). In 1993 Little, Brown offered Hersh and a coauthor a $1 million contract for a book on John F. Kennedy that would illuminate his sexual escapades; he also obtained a lucrative TV deal for the same project. “I started the book on Kennedy,” Hersh told an audience at Harvard in 1998, “for a couple of reasons. One, I had a publisher who was going to give me a lot of money to do it. That’s very important, you know, these days.”

It was Hersh’s first work of tabloid journalism. Early in his research, he was offered an astonishing trove of handwritten documents about JFK—some of which seemed to be written in Kennedy’s own hand—showing, for instance, that he had paid hush money to Marilyn Monroe, given bribes to J. Edgar Hoover, and given instructions to employ the mobster Sam Giancana to manipulate the 1960 election. But the documents were forgeries, and Lawrence X. Cusack, one of the men who peddled them to Hersh, was eventually sentenced to ten years in prison for fraud. The resulting book (minus the forged material), The Dark Side of Camelot, was savaged: in these pages, Garry Wills wrote that Hersh had “obliterated his own career and reputation.” Hersh admitted to the journalist Robert Sam Anson in Vanity Fair that he’d fallen for “one of the great scams of all times,” but he pointed to the occupational hazards faced by investigative reporters: “Any investigative journalist can be totally fucking conned so easy. We’re the easiest lays in town.” When I interviewed Hersh in 2003, he expressed grave doubts about the book, which featured salacious details from members of JFK’s Secret Service team. “I wish they hadn’t spoken on the record,” he told me. “I wouldn’t have used it.”

But Hersh’s career was not quite obliterated. In 2000 he wrote a lengthy article for The New Yorker showing, in great detail, how US soldiers under the command of General Barry McCaffrey had massacred scores of Iraqi troops in the final days of the 1991 Gulf War. (The story, based on three hundred interviews, was sparked by a tip from a retired four-star officer who, speaking of McCaffrey, instructed Hersh to “go get him for what he did.”) After September 11, Hersh wrote dozens of stories for David Remnick at The New Yorker, some of which evinced a hawkish streak that alarmed liberal press critics such as Michael Massing. The young Hersh thought the CIA was too zealously aggressive; the mature Hersh believed, based on what he was hearing from his military sources, that the agency was overly bureaucratic and had to become more effective. In 2003 Thomas Powers recounted a conversation he had had with Hersh before September 11, in which Hersh announced, “Listen, Tom, you gotta understand, this isn’t the CIA that you used to know in Richard Helms’s day. This place has been severely weakened. It’s a lot of geriatric cases and timid careerists.”

Remnick, like Rosenthal, insisted on knowing the identities of Hersh’s anonymous sources. But their relationship frayed, and between 2013 and 2016 Hersh wrote four pieces for the London Review of Books, including a much-criticized account of how Osama bin Laden was captured and killed.* In his work on Syria for the LRB, Hersh insisted, contrary to documentation from Human Rights Watch and the UN, that President Bashar al-Assad was not responsible for the sarin gas attack near Damascus on August 21, 2013.

Hersh, we learn in Reporter, “had met often with Assad by late 2007.” The information he obtained from him, he says, “invariably checked out.” The passages in Reporter devoted to Assad are strikingly friendly. They illustrate the moral dangers of Hersh’s brand of muckraking, which entails a relentless determination to get the story at any cost. As Hersh told Vanity Fair’s Anson in 1997, “You think I wouldn’t sell my mother for My Lai? Gimme a break.” In what seem to be some hastily composed pages near the end of the memoir, he affirms that journalists “tend to like those senior officials and leaders, such as Assad, who grant us interviews and speak openly with us.” Apparently one can kill hundreds of thousands of people and still be a valued source. Hersh tells us that “Remnick was far more skeptical than I was of the integrity of Assad.” The journalist who documented war crimes in Vietnam and Cambodia has overlooked them in Syria.

Hersh’s LRB articles also suggest the dangers of his old reliance on military sources. An article about Syria from early 2016 featured quotes from Lieutenant General Michael Flynn, who was then mostly unknown and whom Hersh depicted as a beleaguered underdog. The notorious Flynn was a dubious source at best. That aside, one wishes that Hersh had spent more time adding texture, nuance, and humility to Reporter. If he had scrutinized his own life with the same tenacity he has directed elsewhere, he might have given us one of the great journalistic memoirs.

-

*

See, for example, Ahmed Rashid, “Sy Hersh and Osama bin Laden: The Right and the Wrong,” The New York Review, September 29, 2016. ↩