The Ukrainian television series Servant of the People, which aired from 2015 until this year, is the story of Vasyl Holoborodko, a dedicated history teacher in his late thirties who lives with his parents. His father is a taxi driver, his mother a neurologist, and his sister a train conductor. This mixture of familial professions would be surprising in an American setting, but it is perfectly logical in Ukraine, where doctors in the public sector belong to the beleaguered lower-middle class, at best. (The average salary for a Ukrainian doctor is around $200 a month.) Vasyl is divorced, with a young son: his marriage was destroyed by money worries. His father tells him he’s wasting time by going to work, since unemployment payments are bigger than a teacher’s salary. The family has a classically Soviet apartment that was given to Vasyl’s maternal grandmother in recognition of her accomplishments as a historian; it is located in a decrepit Khrushchevka, one of the many cheaply constructed apartment complexes that sprouted like mushrooms on the outskirts of Soviet cities in the 1960s.

Poorly paid though he is, Vasyl has a genuine passion for his profession: he stays up late reading Plutarch and loves to regale anyone who’ll listen with lectures about history. In an early episode, we see him teaching his teenaged students about Mykhailo Hrushevsky, head of the 1917–1918 revolutionary parliament during Ukraine’s painfully short first period of national independence. Before the lesson on Hrushevsky is finished, a school functionary arrives to say that class is canceled; the students have to nail together voting booths for the upcoming presidential election. Vasyl loses his temper, and one of the students surreptitiously films his expletive-filled rant about how history matters—unlike the election, which is a farce that offers no meaningful choice and no way out of the corruption that plagues Ukraine.

The video goes viral, a crowd-funding campaign generates a suitcase full of cash to pay for Vasyl’s entry into the race, and before he knows it, he is Ukraine’s new president. In a black car on the way to his first day of work, he holds onto the handle above the window, as if he’s in a tram, and he worries about when he’ll find time to make his payment on the loan he took out to buy a microwave oven. Servant of the People is full of details like this, juxtaposing the grinding financial concerns of ordinary Ukrainians with the absurd privileges enjoyed by the political elite; Vasyl’s handler has the loan forgiven and then asks him what kind of luxury watch he’d prefer. Ordinary people who are tempted by the lure of corruption are treated with laughing sympathy by the series, while oligarchs are cartoonish villains scarfing up caviar as they plot to manipulate and exploit the masses.

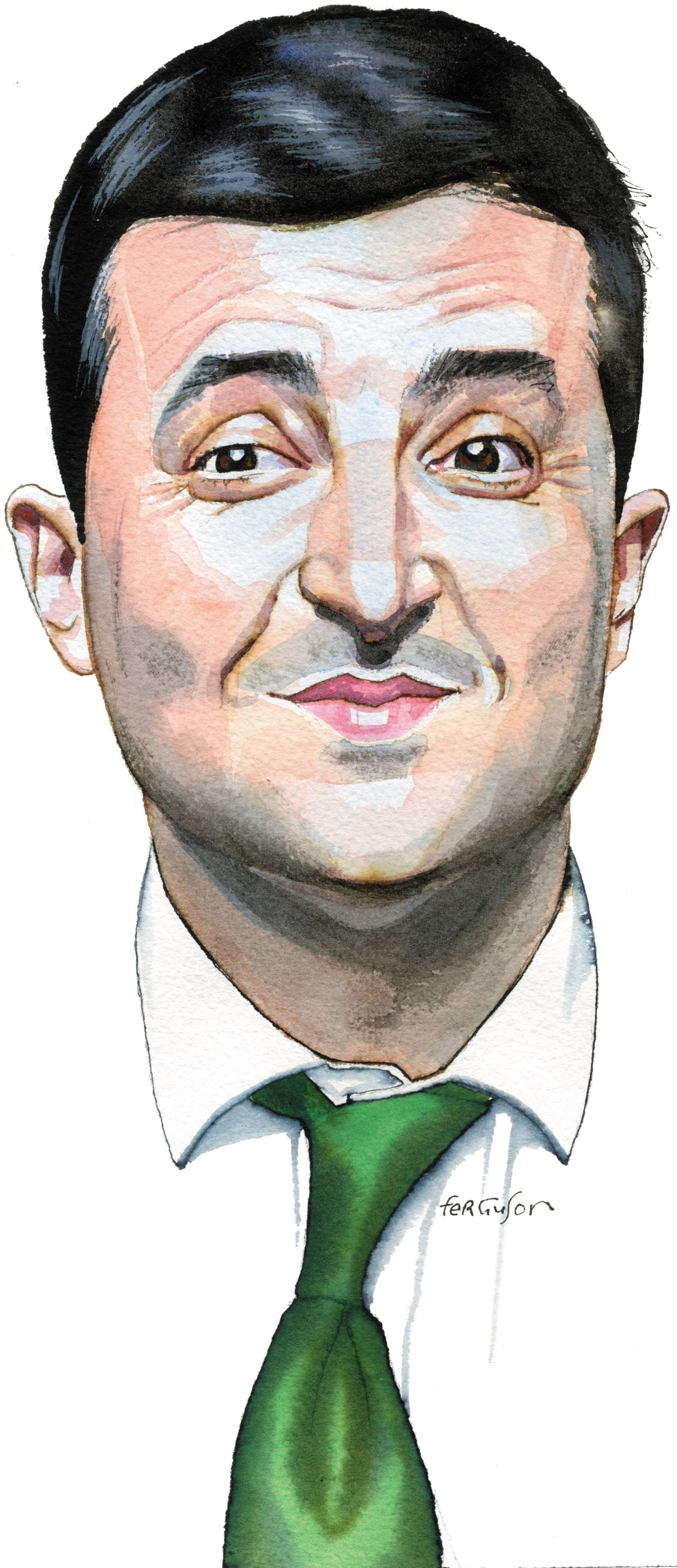

Watching Servant of the People today is an eerie experience. In April Volodymyr Zelensky, the actor who plays Vasyl, was elected Ukraine’s president in a landslide, with 73 percent of the vote. The unpopular incumbent, Petro Poroshenko, who was elected in 2014 shortly after the Maidan protests that ousted President Viktor Yanukovych, received just 24 percent. Zelensky’s newly founded party is called Servant of the People, and his campaign was essentially a spin-off of his show. At first it seemed like a joke: Zelensky is a professional comedian, after all, though he is also a successful businessman at the head of what has often been called a comedy empire. Like Vasyl, he has no previous political experience, though he has connections that Vasyl could never have dreamed of.

Some observers have compared Zelensky to Trump. Apart from the obvious—the TV shows, the blurring of entertainment and politics, the exploitation of popular disgust at perceived government dysfunction—there are a few other common features. Trump’s famous line on The Apprentice was “You’re fired!” On Servant of the People, one of Vasyl’s first acts when he takes office is to attempt to fire 90 percent of government functionaries—though he is motivated by the wish to pay the back wages owed to teachers and other more useful public employees. Trump promised to “drain the swamp” of Washington, while Zelensky’s main campaign issue was government corruption.

Trump, however, ran on a platform of hate, fear, and aggression. Zelensky, who is charming, engaging, and just forty-one years old, ran on a platform of reconciliation. His last name derives from the word for “green,” and his impressively produced campaign videos featured two dots in the Ukrainian national colors, blue and yellow, merging to become a single green circle. Trump’s vision is of two Americas engaged in deadly battle; judging from Servant of the People and from his real-life campaign statements, Zelensky seems to imagine his ideal Ukraine as a happy family whose members accept one another’s differences and do their best to get along, behaving honorably and managing their households responsibly. National finances bear little resemblance to home economics, but Zelensky’s small-government rhetoric appealed to voters disgusted with the political status quo. In his inaugural speech, he quoted Ronald Reagan, another actor-turned-president, saying, “Government is not the solution to our problem; government is our problem.”

Advertisement

Ukraine today faces two huge, intractable problems: a dismal economy and the continuing conflict in the largely industrial eastern part of the country, where Russian-backed, though not entirely Russian-controlled, separatists have established “People’s Republics.” These troubles are interrelated: the loss of the eastern regions and the conflict with Russia, traditionally one of Ukraine’s biggest trading partners, have severely disrupted Ukraine’s economy. The Maidan protests were fueled by anger over pervasive corruption and economic inequality, but the Poroshenko administration is widely perceived as having failed to improve things. Economic concerns clearly played a large part in Zelensky’s landslide victory, as did a desire among voters to end the war in the east.

Much of the criticism of Zelensky from Ukrainian commentators, however, has been connected to a more abstract question: that of language policy. Zelensky’s primary language is Russian, though he can speak fairly good Ukrainian when he wants to; in this he resembles many Ukrainians. Servant of the People is essentially a Russian-language show, but as in real-life Ukraine, characters slip easily from Russian into Ukrainian. Vasyl’s father switches to Ukrainian when he’s talking to the traffic police; official place-names and functions are sometimes given in Ukrainian in an otherwise Russian-language sentence. There are multiple examples of what the Ukrainian-American linguistic anthropologist Laada Bilaniuk has called “non-accommodating bilingualism,” in which one person speaks Ukrainian and the other Russian. Each understands the other, but neither moves to switch languages.

This bilingualism is a fact of life in Ukraine, even within families. It becomes a matter of contention during periodic debates about language policy, which politicians have often used, along with controversial policies on historical commemoration, as a wedge issue. (Since the Maidan protests, these questions have also become the domain of far-right nationalists who exert an outsize influence on the government, in part because of their willingness to make credible threats of violence.) Debates about language policy provide fodder for Russian and separatist propaganda that aims to convince Russian-speakers that they are under attack from the Ukrainian authorities.

Poroshenko made the promotion of Ukrainian one of his main campaign issues, connecting it to the conflict in the east: his slogan was “Army. Language. Faith.” One of his last acts before Zelensky’s inauguration on May 20 was to sign a new law that mandates the use of Ukrainian (already the country’s sole official language) for all public sector workers, with quotas on language use for TV, film, and books. A portion of the Ukrainian population—largely the nationalist-minded intelligentsia—is vehemently opposed to the use of Russian in public life, seeing it as a direct continuation of centuries of Russian oppression. The popularity of Servant of the People and Zelensky’s landslide victory, however, indicate what is already obvious to anyone who has spent substantial time in Ukraine: such linguistic purists are in the minority. Zelensky offered a mild, measured criticism of the new law: though he agreed that Ukrainian should be the country’s only official language, he preferred positive incentives to “bans and punishments.”

In a group interview with foreign and Ukrainian reporters in March, in response to a question about the importance of the Ukrainian language to Ukrainian identity, Zelensky gave a more expansive explanation of his approach to language:

The 10th article of the Constitution of Ukraine [says], “The Ukrainian language is the state language. The country and the government should support and develop the Russian language and the languages of minorities.” [Having quoted the law in Ukrainian, he switches back to Russian]… It’s not necessary to suppress Russian. But of course we are living in a revolutionary moment for the Ukrainian language. The Ukrainian language is a wonderful language when people speak it correctly, beautifully—it’s stunning. Everyone switches to Ukrainian with great pleasure. Our education system is currently set up so that everyone will speak Ukrainian. The next generation will all speak Ukrainian.

This statement was characteristic of Zelensky’s approach: short on specifics, but warm and positive, emphasizing beauty and pleasure rather than, as often happens in discussions of Ukrainian language policies, stressing animosity between Russia and Ukraine.

Zelensky explained his approach to language in relation to the embattled east:

We need to win the information war, starting with the currently occupied territory. We need to reach people in the Donetsk People’s Republic, the Luhansk People’s Republic. They’re Ukrainians….We need a high-quality Russian-language, European-style information service to explain to them, to push the message, “We are Ukrainian—you’re there—you’re our people.”

A Russian-language news service that promotes a sense of Ukrainian belonging among people in occupied territories certainly won’t resolve the conflict. But it would be an improvement on the policies and rhetoric of recent years, which has blockaded and vilified Ukrainians in occupied territory, a strange approach for a government that claims to want reintegration of the lost lands. There are currently two lawsuits pending over the social policy minister’s recent comment that people who have remained in occupied territory are “scum,” and he is far from the only government official to express such sentiments since the war began in 2014.

Advertisement

For Zelensky, the occupied territories are close to home: he is from Kryvyi Rih, a polluted industrial city in the central-eastern Dnipropetrovsk region.* While he often speaks in a wry tone, in keeping with his original profession, he sounds passionately sincere when he talks about his desire for a ceasefire in eastern Ukraine. Zelensky offers virtually no concrete suggestions about how to achieve this, however, and says that he is unwilling to make certain compromises, such as ceding territory or allowing the reintegration of the Luhansk and Donetsk People’s Republics as semi-autonomous regions; without such concessions, Russia might well reject a deal. He professes a staunchly pro-European and pro-NATO stance, ascribing his position to the Ukrainian consensus (which he perhaps exaggerates) on these questions, as well as to personal preference. While this is reassuring to Western governments and to the IMF, it would also likely stand in the way of a successful deal with Russia (if such a thing is even possible), since Russia’s actions in Ukraine have been motivated largely by a desire to keep it out of the European and American spheres of influence.

Starring in a TV show is easier than running a country. Zelensky’s most immediate challenge was a hostile parliament. The obvious solution was to call a snap election. But on May 17, the parliamentary coalition collapsed after one member party withdrew, in an attempt to avoid early elections. Nevertheless, Zelensky announced the dissolution of parliament at his inauguration, based on his own team’s contentious interpretation of Ukrainian law. Now ex-president Poroshenko, Volodymyr Groysman, who just resigned his post as prime minister, and other members of the old guard are scrambling to prepare for an election in July, creating new parties and rebranding old ones. It remains to be seen whether Zelensky can follow his presidential victory with a parliamentary one.

Another potentially crippling blow to Zelensky’s popularity could come from the IMF. Ukraine desperately needs to receive the next installments of its IMF loan: another $1.3 billion this year, contingent on satisfactory reviews. In return, of course, the IMF demands wildly unpopular austerity measures—for example, it pressured Ukraine into increasing household energy prices by 23 percent in 2018, with a commitment to raise them by another 15 percent this May. But the Poroshenko administration chose instead to cut prices during an election season. If the next tranche from the IMF is withheld, which is possible, Zelensky will face economic difficulties that cannot be resolved with cheerful self-reliance. He voiced his support for the pre-election price cuts; if he backtracks now, he risks infuriating voters who elected him in the belief that he would rescue them from their financial troubles.

And then there are the oligarchs. Poroshenko is himself the “chocolate king,” owner of the successful candy company Roshen as well as many other assets; his election after Maidan was an early sign that the protests had fallen short of their objective. One of the most frequently raised concerns about Zelensky has to do with his ties to the oligarch Ihor Kolomoisky, who owns the group to which Zelensky’s television production company belongs and who has a large stake in the television station 1+1, which aired Servant of the People. Kolomoisky is best known as one of the controlling shareholders of PrivatBank, Ukraine’s largest commercial bank.

In 2016 Poroshenko launched a campaign against Kolomoisky, dismissing him from his position as governor of Dnipropetrovsk, where he had successfully warded off the threat of separatism. PrivatBank was found to be running a huge deficit, thanks to dubious loans given to companies controlled by its own shareholders, including Kolomoisky, and it was nationalized and recapitalized at vast cost. Kolomoisky left for Switzerland and Israel, and only came back to Ukraine on May 16. (A lower court judge recently ruled that the nationalization of PrivatBank had been illegal, which surely encouraged him to return.) Though Zelensky has repeatedly and vehemently denied that he is in thrall to the oligarch, Kolomoisky’s return suggests that he believes that he is now safe in Ukraine. On May 25, Kolomoisky proposed that Ukraine reject IMF austerity and default on its external debt.

Further hackles have been raised by Zelensky’s ties to the lawyer Andrei Bohdan, Kolomoisky’s counsel on matters pertaining to PrivatBank. While continuing to represent Kolomoisky, Bohdan has acted as a lawyer and political adviser to Zelensky. In a damaging interview in late April with the newspaper Ukrainska Pravda, Bohdan bragged about his status as a contracted lawyer for the Servant of the People party and as Zelensky’s confidant, claiming that he was the one who had inspired Zelensky to run. On May 21 Zelensky appointed Bohdan as his chief of staff, despite the fact that Bohdan is technically banned from the government due to his service in the Yanukovych administration. What would Vasyl Holoborodko say?

In Servant of the People, an adviser has Vasyl practice delivering his inaugural speech with walnuts in his mouth, “just like the Greeks.” “Dear Ukrainians,” Vasyl begins, “a quarter of a century ago we started building a new nation, conceived in liberty, and with a belief in equal rights for all citizens.” He removes the walnuts from his mouth. “Isn’t that the speech Abraham Lincoln made in Pennsylvania in 1863?” he exclaims indignantly.

“Nobody here will notice,” his adviser reassures him, “and Lincoln’s homeland will praise it. You’ll have to ask them for money soon.”

That evening, the ghost of Abraham Lincoln appears to Vasyl. (Other ghostly visitors seen on the show include Plutarch, Herodotus, Julius Caesar, and Che Guevara, who grows furious when as president Vasyl refuses to execute or even “reeducate” corrupt officials.) “You don’t need my speech,” Lincoln says kindly, “you had a great one of your own on YouTube!” He urges Vasyl to liberate Ukrainians from their bondage, so that ordinary people will no longer have to “break their backs” to pay for oligarchs’ mansions and limousines.

At his modest inauguration at the House of Teachers, Vasyl begins to deliver the Ukrainianized Gettysburg Address—and stops short. “I’m a simple history teacher,” he says, switching to Russian.

Some story: a history teacher makes it into history. Hilarious. According to the plan, I was supposed to promise you many things now. But I’m not going to make promises. First of all, it’s dishonest, and second, I’m not good at it…. But I do know that the most important thing is to be able to look into children’s eyes and not be ashamed.

He switches back to Ukrainian: “I promise you that.” With his furrowed brow and gravelly voice, Vasyl is the picture of earnestness. His cynical handler, Yury, sees his rejection of promises as a brilliant political success, a great improvement on the usual tactic of making pledges one has no intention of keeping.

Zelensky’s election recalls the story of Jón Gnarr, the Icelandic actor, writer, and stand-up comedian who ran a satirical campaign for mayor of Reykjavik with the Best Party in 2010 and won. His supporters were furious at the financial irresponsibility that had caused Iceland’s bank collapse in 2008, and at the idea that taxpayers should be liable for the resulting debt. Thanks in large part to mass protests, Icelandic banks were denied a bailout and the prime minister was driven from office and convicted for his part in the crisis. Nevertheless, there remained an enduring sense that the existing political parties offered no meaningful choice. “Things have gone sour/It’s time to clean up,” the Best Party sang, to the tune of Tina Turner’s “Simply the Best,” in a campaign video that offered promises such as “A drug-free parliament by 2020!” and “Do away with all debt!”

Zelensky has drawn a much greater distinction than Gnarr did between his comic persona and his political one, but he can’t—or won’t—fully repress his well-honed sense of humor. He refused to debate Poroshenko in a TV studio, insisting instead on a soccer stadium. He challenged his rival to a drug test before the debate and then livestreamed his own blood test, laughing and toasting his audience with the plastic cup of water the lab technician gave him. Exasperated by Poroshenko’s eleventh-hour appointments to the Supreme Court, the army, and other institutions, Zelensky remarked:

The situation reminds me of a tourist in an Egyptian hotel: heading home tomorrow, the suitcases are packed, the room has already been cleaned. A normal, educated person is waiting for a transfer to the airport. But not Poroshenko. He won’t stop. He starts taking the towels, slippers, and everything from the buffet. I beg of you: hand over the key, pay for the mini-bar, and go. You still have to go through customs and passport control.

Gnarr did not seek reelection; he was reportedly exhausted by his duties, which brought him to the brink of tears in public. “It’s just so boring!” he often told the Best Party’s sole employee, who had to give him pep talks to keep him in office. Zelensky has already vowed to serve only one term. He concluded his real-life inaugural speech by saying, “Throughout my life, I’ve tried to do everything I can to make Ukrainians smile…. In the next five years, I will do everything to ensure that you, Ukrainians, don’t cry.” One wonders how long it will be before he himself stops laughing and bursts into tears.

—May 30, 2019

-

*

Zelensky’s victory was especially overwhelming in the largely Russian-speaking eastern and southern regions, where he won between 87 percent (in Kharkiv) and 89 percent (in Ukraine-controlled Luhansk). ↩