In a series of conversations with Merve Emre at Wesleyan University, some of today’s sharpest working critics discuss their careers and methodology, and are then asked to close-read a text that they haven’t seen before. The Review is collaborating with Lit Hub to publish transcripts and recordings of these interviews, which across eleven episodes will offer an extensive look into the process of criticism.

If you read criticism regularly, then you start to develop a list of writers whose bylines you look for with every new issue of the magazines that you read. For me, Sophie Pinkham is one of these writers. She is a professor of comparative literature at Cornell University. Her essays on art and literature under autocracy have been models of how to ask questions about aesthetics and politics, form and power, with tremendous precision. Her writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Economist’s 1843 Magazine, The New Yorker, New Left Review, and The Washington Post. She’s also a regular contributor to The New York Review, which has published her essays about Ukrainian and Russian novels, modernist architecture in Communist Yugoslavia, socialist realist painting, and, my favorite, post-Communist Russian feminism and feminist poetry. Her book Black Square: Adventures in Post-Soviet Ukraine blends reportage and memoir in a brilliant and disturbing examination of how history is manipulated by empires to serve their nationalist, xenophobic land lust. Her next book, tentatively titled The Spirit in the Trees, is a cultural history of Russia’s forests.

Merve Emre: Many people in the audience tonight are eighteen-, nineteen-, twenty-, or twenty-one-year-old college students, and you are here in part as a model of how they can get from where they are to where you are. Can you narrate that journey?

Sophie Pinkham: Yes, with pleasure. I think my journey to literary criticism has perhaps been unusually circuitous. I began in a very straightforward manner: I graduated with an English degree. But then I made a strange swerve. As someone who had grown up in New York City, around many people my own age who had emigrated from the Soviet Union as children, I had spent quite a lot of time with people whose native language was Russian. And gradually, as I studied English poetry in college, I became fascinated by Russian poetry, and in particular by the charismatic and sexy Futurist poet Vladimir Mayakovsky.

Can we pause? Tell us what made him sexy.

Well, Russia is a place that has specialized in sexy poets. I think it is partly the charge of social importance that poetry had there. It’s important to know that Mayakovsky died by suicide, certainly in part due to his relationship to political power. In the 1920s he became probably the biggest superstar poet in a nation known for its superstar poets.

He was in some ways the most prominent—the most typical, one might say—poet of the early Soviet project, before it descended into full-blown Stalinism. He was a poet of the Revolution. That, I think, invested him with a social energy that was deeply appealing. He also, to my adolescent mind, looked quite handsome in photographs. I learned later I was not the only one who had this slightly twisted appreciation of the physical appearance of Vladimir Mayakovsky, whose photo, I must confess, still adorns my wall. He inspired me.

He also appealed to the New York poets in the Fifties and Sixties, notably Frank O’Hara and Kenneth Koch. I had a lot of friends in New York who were aspiring poets, some of whom are also now critics of various kinds, and who studied with Kenneth Koch while he was still alive. There was this connection between enthusiasm for Russian Futurism and the New York School and John Ashbery, who also became a favorite of mine when I was in college.

Okay, so hot, powerful, revolutionary, transnational.

My confused adolescent yearnings led me to study Russian for a year at the end of college. Then I didn’t really know what to do with myself. I had a vague desire to become a novelist, but I felt, in a quite old-fashioned way, that I should, like Melville, take to the high seas, so to speak, and that it was absolutely necessary for me to go as far away as possible. I found an advertisement for an exchange program. It’s amusing to imagine this existing now, but it was a Russian-American exchange program for young people.

What year are we in now?

This was in 2004. A long time ago. I applied for this exchange program, and I didn’t know where they would place me. It had to do with public health, which was another thing that I was interested in. In college I had been involved in AIDS and reproductive rights activism. I was placed at the Red Cross in Irkutsk, which is in Siberia. Some of you might know it from the board game Risk. That was the only way that anyone knew Irkutsk.

I was there in late November and December. Irkutsk is very deep in Siberia, near Lake Baikal. It’s immensely cold. At the Red Cross there, the two main health problems they dealt with were HIV, because there was a huge epidemic in Russia, and frostbite. So that gives you a picture of Irkutsk at that time. I became fascinated by the problems of post-Soviet public health. When I returned, I ended up getting a job at George Soros’s foundation. I also became deeply interested in Soviet history and the transition from the Soviet Union, in how societies were transformed and how the people of different countries redefined their identities—sometimes casting off the Soviet legacy, sometimes clinging to it, sometimes retrieving old forms of nationalism.

Advertisement

I ended up getting a Fulbright grant and living in Ukraine for several years. Then I got a job and stayed on even longer in Ukraine, and really fell in love with Ukraine. This is extremely bizarre in light of current events, but that was where I learned Russian. I couldn’t say it was complete immersion in Russian, of course, because it was Ukraine, and I was living in Kyiv, which was a bilingual city at that time. It still is bilingual in the sense that everyone there can speak Russian and Ukrainian, but for obvious reasons most people at this point choose not to speak Russian anymore. They speak to each other only in Ukrainian. But at that point Russian was probably the predominant language in Kyiv. Bizarrely, I got an American government grant to learn Russian in Kyiv.

You’ve said “bizarrely” twice now, and I want to press you a little bit on what makes it feel bizarre. Could you reflect a little on getting the language education that you did, in the place that you did, given the events of the present?

I think I was attracted to that part of the world because it was in transition. I certainly had no understanding at all of where the transition was going to lead, of the next turning point, which was, of course, Russia’s horrifying violence toward Ukraine, its support of separatists, who annexed eastern Ukraine in 2014 with the support of the Russian military, and now the full-blown war, which all of you are very aware of. Although of course it resonates with other parts of Russian history, such as the Russian Revolution, and with this profound uncertainty, this feeling of teetering on the edge of an abyss that has characterized a lot of Russian literature and Russian culture.

Take us back to your story: you are in Ukraine, you are studying. Were you in graduate school at this point or still on your Fulbright?

I was still on my Fulbright. Then I went to graduate school to do Slavic studies. I had become entranced by Soviet culture. In the early Soviet Union, there was a great blossoming of all kinds of culture, not necessarily in the Russian language or specific to Russia—Ukrainian modernism, for instance. I ended up doing a Ph.D. in Slavic. Then there was the dramatic turn of the Maidan Revolution in 2013–2014, when protesters gathered and stayed in the center of Kyiv for many, many weeks and ended up driving out then-president Viktor Yanukovych. That was what helped trigger Russia’s first attack on Ukraine.

This is where I would give you advice, if you will accept advice: it helps to have a strange expertise. The American job market is full of people who speak only English. It turns out that having somewhat unusual language skills can set you apart. Having experience in some other part of the world can also be enormously useful. It gives you a starting point. It becomes a sort of calling card for you. When the Maidan protests happened and the war in eastern Ukraine began, I think I had published one or two magazine pieces. I was just starting graduate school. But I was one of the only people on the writing scene who had any deep experience of Ukraine.

I want to go back to something that you said about Mayakovsky: that there was a great social importance to poetry. The sense that art has social importance is something I feel very strongly when I read your essays and, if I can be a little provocative, it’s not something that I always feel when I read academic writing. I think one thing you’ve managed to do wonderfully is take that strange expertise—an expertise that in some ways could only be cultivated in or adjacent to a university—and use it to make us feel the power and social potential of art. Can you talk a little bit about how you think about these questions of art and social importance in the context of the essays you’ve written for, say, The New York Review of Books?

Going back to Mayakovsky—and thank you for circling back to him—part of what made me so interested in Russian literature and culture, as someone who had from early childhood been passionately interested in literature, was the prominence of poets and writers. It was immediately apparent to me, even as a naive, confused foreign exchange student who barely knew Russian, that a very large proportion of streets in Russia are named after writers. The toppling of monuments to canonical Russian figures and poets, such as Pushkin, who have become symbols of imperial power has been very symbolically important in places such as Ukraine. I was fascinated by that close linkage between literature and politics, which was not something that I felt strongly in America.

Advertisement

In my criticism, it is just a fact that literature and other forms of culture in Russia have been much closer to political power historically and have been used as tools of political power. One thing that I’m interested in doing is looking at ways in which that still might be true. Today there is a reflexive tendency to think of literature, and also other forms of culture, as an extra, as an ornament, as icing on the cake, as something that is expendable and unnecessary. The core of power is, I don’t know, money, politics, weapons, right? But I think it’s worth asking whether there is a current of power that is always in literature and culture even at times when it’s less explicit.

Can you talk a little bit about how you distinguish between the image of a writer that has been created and put into circulation and the poet or the poetry itself?

You want to keep returning to the poetry itself. Part of it has to do with reading as much of the person’s work as you can. For example, with Pushkin, what proportion of his work is objectionable Russian nationalist poetry? And he did write a few very politically objectionable nationalist poems, which have recently been circulated online. The same is true of Brodsky. In this atmosphere of memes and reposts, the fury they generate is understandable.

But suddenly, those few poems become the key representation of that poet. You should absolutely take those poems into account. Some of Pushkin’s most objectionable poems have been used as political tools and been important building blocks in the creation of this poet’s image as a nationalist icon. But you also want to understand their other poetry. You want to situate that poem in the person’s career. When did they write that poem? Why did they write that poem? What was the context of that poem?

I wonder if I could give you something to read, and if you could put your mind to work on an object that I think bears a great deal of power. I’m curious to hear what you think about it. I would ask perhaps that you first start by reading it aloud for us, and then describe it. Then perhaps read aloud whatever parts of it you feel might be important for your performance of criticism.

New York Review Books/New Directions Publishing Corp.

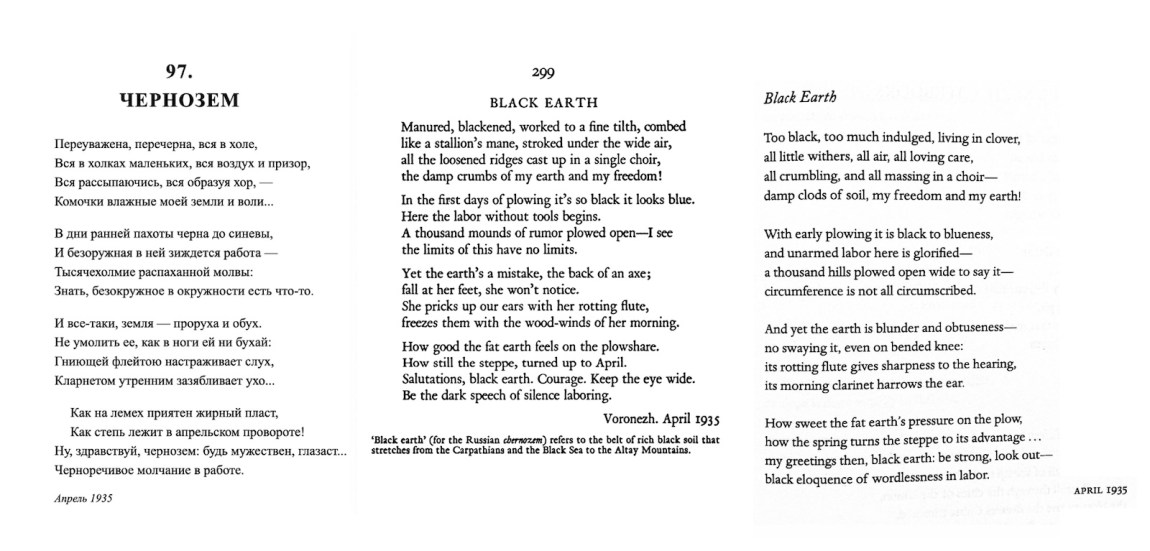

From left: The original Russian text of Osip Mandelstam’s “Black Earth” (1935); Clarence Brown and W. S. Merwin’s 1971 translation of the poem from The Selected Poems of Osip Mandelstam (New York Review Books, 2004); and Peter France’s translation from Black Earth (New Directions, 2021)

This is a poem called “Black Earth,” or “ЧЕРНОЗЕМ,” and it is by Osip Mandelstam, who is one of the greatest writers of the Soviet period, and one of the many writers who was killed by Soviet power.

For those keeping track, Sophie is the first guest to correctly identify the object that she has been given. Well done.

This is one of his more famous later poems. It was written near the end of his life, when he was in exile in Voronezh. “Black earth” refers to the extremely fertile soil in the steppe area of central Russia and Ukraine. I suspect that Merve may have cleverly chosen this poem because it does connect to my book, and to Ukraine, because one reason that Ukraine has been coveted by Russian power is its extremely fertile soil.

In true Mandelstamian fashion, this is a poem that is extremely difficult to translate. I wrote for the Poetry Foundation about Peter France’s excellent translations of Mandelstam’s poetry. He has, I believe, two collections of translated poems that came out with New Directions. They’re outstanding. But Mandelstam’s poetry is immensely difficult to translate because it is this tissue of living sound. I should perhaps read a little bit of it.

Why don’t we read it comparatively, stanza by stanza. Do you want to read the first stanza of the first translation and the first stanza of the second translation that I’ve given you here, and then tell me how you think about these comparative translations?

In the first translation, the first stanza goes:

Manured, blackened, worked to a fine tilth, combed

like a stallion’s mane, stroked under the wide air,

all the loosened ridges cast up in a single choir,

the damp crumbs of my earth and my freedom!

And then in the second translation, it reads:

Too black, too much indulged, living in clover,

all little withers, all air, all loving care,

all crumbling, and all massing in a choir—

damp clods of soil, my freedom and my earth!

How do you even begin to approach these two very different translations?

One thing they show clearly is that Mandelstam’s poetry—and I think that this is true probably of all poetry and definitely of all good poetry, but it’s unusually true of Mandelstam’s—depends on the interaction of multiple meanings of words, of what they indicate literally and their sounds, their connotations, their moods. This is very difficult for a translator because he or she is immediately faced with overwhelming and perhaps panic-inducing ambiguity.

The first word of this poem in Russian is “Переуважена” [pereuvazhena], which is a more or less made-up word. It is formed using Russian’s ability to add a prefix to almost any word in order to change its meaning. The prefix, “Пере,” appears for a second time in the next word, “перечерна” [perecherna], which means “too black” or “over-blackened.” But this first word, “Переуважена,” comes from the word for “respect.” And onto it has been attached this prefix that can mean “repeatedly” or “excessively” or sometimes “across.” That’s quite abstract. It could mean “repeatedly respected,” “excessively respected”—something along those lines. But what does that mean? And then you continue reading and you realize that this is all referring to earth. What does it mean to say that the earth is “over-respected” or perhaps “repeatedly respected,” or, as the first translation has concluded, “manured”? There are a staggering variety of possibilities.

Is that a fair conclusion? That “manured” is a corollary to “too much indulged”?

Perhaps. Can you imagine that you’re a translator and you’re choosing between “manured” and “overindulged”? I am not sure, frankly, how the translator got to “manured.” There might be an agricultural connotation to that word that I’m not aware of. But these are the choices that confront the translator.

One thing that the translator has to think about is to what extent Mandelstam is being governed by the sounds of words. Even if you can’t read Russian, you can see the pattern of all the xs. Look at all the xs in that first stanza. There’s “холе” [khole], and then “холках” [kholkakh], which is “withers,” and then “хор” [khor], which is “choir.” When you’re a poet, often you’re choosing words not exclusively because of their sound, but largely because of their sound, because that’s how you’re composing your poem. This is a more or less rhyming poem.

You have this special expertise, which we talked about, and it has been cultivated through years of immersion and study. Then you encounter these two versions of a poem that bears a particular force and a particular social power. How do you judge? I assume it’s not a criterion of one-to-one fidelity—saying, this word is more faithful to the original than this word.

There are two schools of translation. The first one is all about so-called fidelity. And that is much more the one-to-one school. Nabokov is one of the most passionate advocates of this one-to-one school of translation and wrote many angry, disgusted polemics against anyone who used their judgment. Even the word order, he thought, should not be changed, which led him to make some really bad translations in my view. I’m not a fan of the one-to-one, simply because you end up with a lot that is unintelligible—with extremely convoluted phrases in the English when the original is quite straightforward, and sounds very natural and light and doesn’t draw attention to itself.

I am more in the school of translation as a sort of inspired approximation or even re-creation, a reinvention. I think that this is especially true with poetry. Poetry is not something that you can translate in a one-to-one sense, unless it’s quite bad, simple poetry. Good poetry needs to be reinvented. I think that’s part of the reason that often the best poetic translators are poets themselves.

Whose reinvention is more appealing to you? Is there a better reinvention here?

I prefer the second one. The first one has this final line, “Be the dark speech of silence laboring.” That’s very bad. That’s very, very bad.

Let’s work our way there. Let’s take the next two stanzas together.

In the first days of plowing it’s so black it looks blue.

Here the labor without tools begins.

A thousand mounds of rumor plowed open—I see

the limits of this have no limits.

Yet the earth’s a mistake, the back of an axe;

fall at her feet, she won’t notice.

She pricks up our ears with her rotting flute,

freezes them with the wood-winds of her morning.

And then in the next translation:

With early plowing it is black to blueness,

and unarmed labor here is glorified—

a thousand hills plowed open wide to say it—

circumference is not all circumscribed.

And yet the earth is blunder and obtuseness—

no swaying it, even on bended knee:

its rotting flute gives sharpness to the hearing,

its morning clarinet harrows the ear.

To me, what immediately jumps out is how in those third stanzas the earth becomes “she” in the first translation, “She pricks up our ears with her rotting flute,” rather than in the second: “Its rotting flute gives sharpness to the hearing.” Can you talk about those choices?

That decision has to do with having gendered nouns in Russian and not in English. It’s a moment for the translator’s discretion. Do you want to reproduce the more literal option, which is to give the earth a gender? It makes it feel like a gendered poem in a way that it really doesn’t feel in Russian, because in Russian it’s completely natural for every noun to have a gender. You don’t think about it so much. I’m sure a lot of you speak some language that has gendered nouns—many languages do—and you don’t think of the noun, especially a commonplace noun, as being necessarily associated with people of that gender. Whereas when you make that choice in English, it produces an interpretation, especially with a poem of this complexity, of this elusiveness, of this ambiguity.

The translator is doing a huge amount of interpretive work, and the translation really succeeds or fails based on the interpretation, but also on the translator’s ear. One thing that I like in this second translation is that it does a better job of intimating that this is a poem largely about sound. It does so without trying to fully reproduce the specific scheme of rhyme and meter, which is a very dangerous game, especially given that English is a language in which it’s much harder to make rhymes than Russian.

So as an English reader who has no access to the Russian, you can still see that sound is important. It matters in the first stanza—for example, in “all air, all loving care.” There’s a little rhyme that the translator was able to squeeze in there, within a single line. That’s important, whereas the first translation is more of the kind of conversational, plainspoken style of poetry, which is, of course, wonderful in its own way. There are some lovely lines there, but I think it is much less true to Mandelstam’s own approach.

Let’s speak about the final stanza.

How good the fat earth feels on the plowshare.

How still the steppe, turned up to April.

Salutations, black earth. Courage. Keep the eye wide.

Be the dark speech of silence laboring.

And the second one:

How sweet the fat earth’s pressure on the plow,

how the spring turns the steppe to its advantage . . .

my greetings then, black earth: be strong, look out—

black eloquence of wordlessness in labor.

To me, there’s a huge difference between “silence laboring” and “wordlessness in labor.”

As I said, I think that the final line of the first translation sounds really bad, twisted and convoluted and awkward, and you have to pause to parse it. When you try to translate Mandelstam, or you study him intensively and parse his meaning, it’s really difficult to analyze the grammar and figure out what’s going on. Even for native Russian speakers, it can sometimes be confusing. You’re hit by the overwhelming sensation of the poem before you’ve parsed exactly what is going on with the words.

I think that the translation has probably failed if it doesn’t hit you with a feeling before you’ve had a chance to figure out what the words actually say. For me, at least, “be the dark speech of silence laboring” doesn’t hit me with any feeling. It just makes me think, What are you talking about? “Black eloquence of wordlessness in labor” is still pretty complicated, but it does better.

Let us say you were writing an essay in which you were talking about two different translations. Where do you go from here? You have made these observations, but how do you use them to make a larger argument or tell a bigger story?

Partly because I find this is what readers tend to enjoy, I put the poet or writer in a larger story. I would place this late Mandelstam poem in the context of his exile to Voronezh in central Russia as part of the story of his impending death, which he sensed. He was having this final, tragic outburst of writing before he died in the Gulag, and he produced these poems that had a strange admixture of creativity and menace.

There is something quite menacing in this poem, and disturbing. There’s the rotting flute and the back of an axe. I like that the first translation keeps the “back of the axe.” There’s something really threatening, but there’s also this magnificent fertility and abundance of the earth. I think it’s important to root, if you will, that tension in Mandelstam’s biography and in the larger events he was involved in, Stalinism and the purges under Stalin.

You have the poem, which you situate in a biography, and then you situate the biography in a political context or condition. What are the difficulties of reading poems biographically and of reading biographies politically? You also do this in your essays, and I think you manage to find the right balance.

It’s funny that you ask that, because my training as an undergraduate was during the days at Yale when the analysis of poetry was rooted in the New Critical approach, which was antihistorical. We would have no historical context. The idea was that you would sit there with a poem in a black box, and it was irrelevant how the poem related to the poet’s biography. I was taught about the biographical fallacy, that it was irrelevant to know the historical time the person was living in.

I loved that. I thought it was fantastic. I took so much pleasure in it. I sought those classes out when I was an undergraduate. I took only classes in close-reading poetry. I didn’t take any prose classes. I didn’t take a single history class the entire time I was an undergraduate. All I wanted to do was to sit there rigorously reading poetry in a void.

I wrote my senior thesis on Emily Dickinson’s poems in which the speaker is already dead but is still writing a poem. And as I was reading I realized that a lot of her similes were direct references to specific conventions of mourning and death during the Civil War. It was a time of mass trauma, when so many people were dying, including a lot of young people. I started to feel that as much as I loved reading poems in a void, I wanted also to know what was going on historically. It completely changed my feeling about Dickinson’s poems and my understanding of them. I didn’t love them any less. They were less enigmatic, but also brighter. I liked having the story to attach them to.

I think a lot of readers also enjoy that. In my writing, I try to maintain a respect for great literature as something that can always be read with pleasure, with joy, and with edification even without that historical context. If it’s truly great, it stands alone. But context is a pleasure as well, and further enriches your understanding of the poem. For me, great writers, like Mandelstam or Dickinson or whoever, exist as living people in the imagination. They’re like your friends at a certain point. And for that, you need to understand their context.

We just spoke about how you might situate this if you were writing an essay for the New York Review assessing different translations of Mandelstam’s work. How would you situate this if you were writing about it in, for instance, the first chapter of a book on the cultural history of forests, the book that you are working on now?

I have been thinking about including Mandelstam in my book about forests. I would start, of course, with the black earth and its history. I don’t know if Mandelstam knew this, but expansion into the super-fertile black earth was what allowed the Russian Empire to grow as it did and become what it was, because that soil allowed much larger agricultural yields. In that sense, it’s a very powerful poem about the relationship between geography and the earth, in the most literal sense, and political power—a political power that destroyed the poet in the end.