The full consequences of President Trump’s decision on October 6 to withdraw American troops and give Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan a green light to invade northeast Syria are not yet clear. Erdoğan claimed that he wanted to create a twenty-mile buffer zone in which perhaps one million Syrian refugees living in Turkey could be resettled, but he may have had the ambition of turning all of northeast Syria over to the Islamists whom Turkey had sponsored in western Syria during the country’s civil war and who were largely defeated there.

Thanks to deft Russian diplomacy, that ambition—which could have reignited the Syrian civil war just as it was winding down—appears to have been largely thwarted. But it is hard to imagine a more calamitous outcome for the United States, the Kurds, NATO, and possibly Turkey itself. Turkey is unlikely to accomplish its stated objective of eliminating Kurdish control of the border zone, while its invasion threatens to rupture relations with the West and lead to sanctions that would further shrink a contracting economy. If it comes to a prolonged fight against the Kurds, Turkey cannot rely on the undisciplined Syrian proxies that it has used so far, meaning large numbers of regular Turkish army troops will be engaged against a skilled and determined adversary. Costly battles with a conscript army are rarely popular at home.

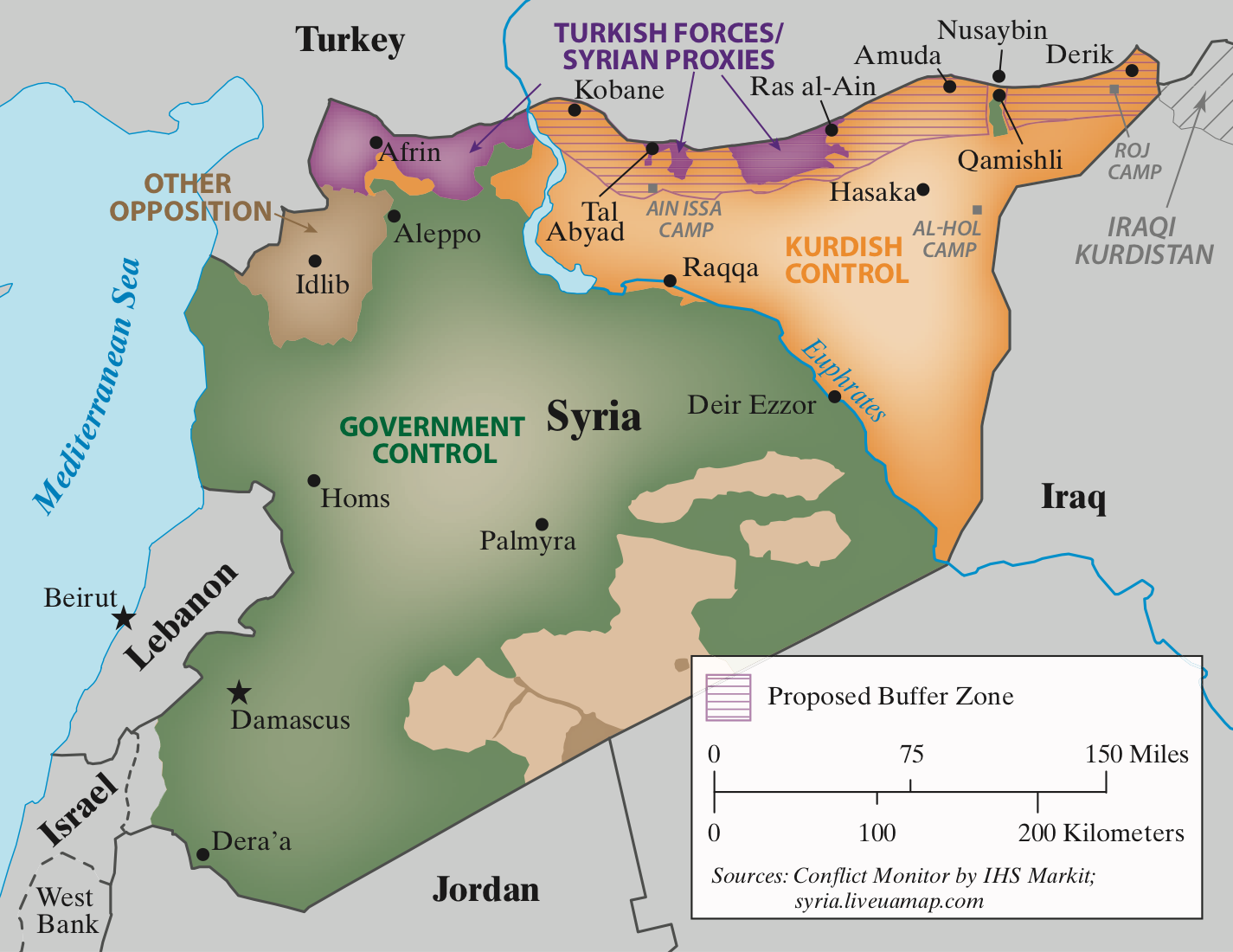

Before the Turkish offensive, which began on October 9, Syria was essentially divided along the Euphrates River (see map below). To the west, the Syrian government had mostly overcome a disparate group of foes, including Islamists, Turkish proxies, warlords, and a small number of Western-oriented democrats. Only Idlib governorate in the northwest remained outside the control of Syrian president Bashar al-Assad.

To the east of the Euphrates, the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) controlled almost one third of the country. With US air support and the assistance of around three thousand US special forces and CIA operatives, the SDF had prevailed in a five-year battle with ISIS, whose “caliphate” had at its peak in late 2014 controlled more of Syria than either the government or the Kurds. During that time, the SDF lost 11,000 fighters, while the US sustained five combat casualties.

By October 13, under the terms of a Russian-brokered deal between the Syrian government and the SDF, Assad’s forces had moved into the major population centers in northeast Syria to support the Kurds and as a first step to reestablishing Syrian government authority in the region. Turkish artillery fired on an American base, and the US scrambled to pull out troops and diplomats. In his public statements and tweets, Trump alternated between defending his green light on the grounds that the Kurds were “not angels” and didn’t fight on the US side in Normandy (neither had Turkey), and threatening to destroy Turkey’s economy if it didn’t stop its offensive. US secretary of defense Mark Esper publicly questioned whether Turkey was an ally. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell finally found something about Trump he didn’t like, as did almost every Republican lawmaker who spoke or tweeted on the subject. And if Iranian hard-liners drank, champagne corks would be popping in Tehran over Trump’s betrayal of the Kurds.

The situation was, of course, most tragic for the Kurds. The major Kurdish cities in Syria are on the Turkish border or very close to it. Qamishli, the largest, is divided from the Turkish city of Nusaybin by a concrete wall. Kobane, the site of the ferocious 2014 siege by ISIS that prompted a US intervention, also backs up against the border wall. Other cities—Tal Abyad, Derik, Rumeila, Amuda—touch the wall or are close to it. In the first days of Turkey’s Operation Peace Spring (an Orwellian designation even by modern military standards), Turkish shelling and air strikes killed hundreds and—along with Turkey’s Syrian proxies—drove 200,000 civilians from their homes.

President Erdoğan alleges that the dominant Syrian Kurdish party, the Democratic Union Party (PYD), is simply an adjunct of the Turkish Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK). The PKK, which was founded in 1978 with the ambition of carving out an independent Marxist state and has since scaled its goals back to seeking some form of autonomy and Kurdish rights, has waged a thirty-five-year insurgency against the Turkish state. Turkey, the European Union, and the US all designate it as a terrorist organization, but the latter two do not consistently treat it that way. Perhaps because it does not engage in attacks outside Turkey, the PKK is allowed to have offices in some European countries. US officials were privately appreciative of the PKK’s rescue in 2014 of Yazidis, a religious minority who had fled from ISIS to the Sinjar Mountains in Iraqi Kurdistan, sparing US forces a risky helicopter airlift. Even though Erdoğan’s government itself has negotiated with the PKK, the Turkish president justifies the invasion on the grounds that Turkey will not allow the creation of a terrorist state on its borders.

Advertisement

Turkey’s claim of a connection between the PKK and the Syrian Kurds is not baseless. Some senior PYD and SDF leaders were not only members of the PKK but fought against the Turkish state inside Turkey. Pictures of PKK founder Abdullah Öcalan are ubiquitous in northeast Syria—in offices, on flags, and on billboards, alongside those of Kurdish martyrs who died in the fight against ISIS. And Öcalan’s ideas continue to have an outsize influence on the Kurds in Syria.

But the Kurds in northeast Syria are no threat to Turkey. There is no credible evidence of any attack on Turkey from Syrian Kurdish–controlled territory. Its flat terrain is ill suited to cross-border attacks or infiltrating terrorists. And Turkey has not always treated the PYD as if it were a terrorist organization. Until 2015, Turkish diplomats and intelligence officials met regularly with the PYD leader Salih Muslim, including in Ankara.

Erdoğan’s shift on the Kurds may have more to do with Turkish politics than with any terrorist threat. Until 2014, his Justice and Development Party (AKP) received a substantial percentage of Turkey’s Kurdish vote, mostly from religious Kurds. This changed in September 2014 when Turkish tanks passively watched as ISIS—armed with US weapons captured from the Iraqi army—assaulted Kobane. In the 2015 elections, Erdoğan lost the Kurdish vote and with it his parliamentary majority. He then repositioned himself as a nationalist, ending peace negotiations with the PKK and denouncing the PYD as terrorists.

Trump’s critics almost invariably speak of the Kurds as the betrayed foot soldiers of our war against ISIS, while Trump, in one of his few cogent explanations of why he withdrew US forces, argues that it was the US that helped the Kurds. In September 2014 President Obama authorized air strikes—and later weapons drops—to support the Kurdish defenders of Kobane, who were fighting a building-by-building battle in the completely surrounded city. But once the Kurds broke the siege of Kobane and recovered the Kurdish-inhabited territory that ISIS had taken, the US insisted that they continue the battle against ISIS in overwhelmingly Arab parts of Syria, including the ISIS capital, Raqqa, and Deir Ezzor, more than one hundred miles south of any Kurdish territory. Many Kurds, including the Kurdish National Council (KNC), a collection of Syrian Kurdish parties opposed to the PYD, did not want to shed Kurdish blood to liberate Arab lands. The SDF sustained most of its 11,000 casualties in the fight for Arab, not Kurdish, territory.

If policymakers looked beyond the Kurds’ military utility, they would see a remarkable social revolution with potential implications well beyond Kurdish territory. As Assad’s opponents captured more land in 2012, the Syrian army withdrew from the strategically less important northeast. The PYD was the strongest of the Kurdish political parties that filled the void there, and it looked to Öcalan for guidance. When he founded the PKK in 1978, Öcalan was a Marxist who modeled himself on Josef Stalin, to whom he bore an uncanny physical resemblance. In 1999 Turkish commandos captured Öcalan in Kenya. Until 2009, he was the only prisoner on İmralı island in the Sea of Marmara. He has had a lot of time to read. With both Marx and Stalin long out of fashion, his lawyers gave Öcalan Turkish translations of two books by my fellow Vermonter Murray Bookchin, who argued for a society based on strict gender equality, direct democracy based on representing communities, and radical environmentalism. Öcalan was impressed and wrote Bookchin in Burlington to say he was one of his best students. Through his lawyers—and occasional visitors—Öcalan also communicated Bookchin’s views to his cadres.

Following Bookchin’s philosophy, northeast Syria’s many communities are represented in multilayered governmental structures. Legislative bodies—city councils or cantonal parliaments—include Kurds, Arabs, Christians, and Yazidis and are equally divided between male and female legislators. Each canton has a male and female co–prime minister, each municipality a female and male co-mayor, and male and female coleaders of each political party. No more than 60 percent of civil servants can be from the same gender. The Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (NES) sits atop these governmental structures. It has a Kurdish woman and an Arab man as its copresidents.

Since 2012, I have worked with several nongovernmental organizations on mediation projects involving the Syrian Kurds, all on a pro bono basis.* These have included efforts to integrate them into the broader democratic opposition to Assad (which failed, since Assad’s Arab foes are as chauvinistic as he is on Kurdish issues), to resolve disputes among the different Kurdish factions within Syria (also unsuccessful), and to mediate between the NES and the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) in Iraq (an effort that began in 2015 at the behest of French president François Hollande in partnership with a longtime friend of the Kurds, former French foreign minister Bernard Kouchner). Most recently, I have been helping the Syrian Kurdish leaders plan negotiation strategies. In these various capacities I have made fourteen trips to northeast Syria and been a witness to the evolution of the administration and, in particular, the participation of women in the military and political struggle.

Advertisement

The NES has shortcomings, of course, and the biggest is an unwillingness to accept real dissent. In the course of my visits, I have met the leaders of at least twenty different political parties, all of whom expressed nearly identical positions on the major issues. Meanwhile, the NES authorities closed the offices of the Kurdish National Council, the PYD’s rival, and periodically arrested or expelled its leaders. During my trips to northeast Syria since 2014, no topic consumed more of my time than the release of political prisoners.

Nevertheless, it is hard not to appreciate the revolutionary nature of what the Kurds have accomplished. In 2016 I traveled to the front line on the outskirts of Raqqa. Members of the Kurdish militia known as the Women’s Defense Units had just captured a police station. They bivouacked with their male counterparts and demonstrated the same mastery of weaponry as the men. An ISIS fighter lay dead among the debris nearby, with an uncertain fate in paradise: ISIS fighters believe a jihadi killed by a woman will not get his seventy-two doe-eyed virgins, a significant disincentive to martyrdom when taking on the Women’s Defense Units.

On my last visit, I was out for a stroll in Amuda, a small Kurdish city in sight of the Turkish border wall, and I passed a TV station. My interpreter suggested we go in. Every employee—from top management to cleaning staff and including anchors, reporters, camera operators, and technicians—was a woman. Jin TV broadcasts four hours a day from Amuda, and its reporters explained the station’s mission as promoting women’s rights by ending child marriages and polygamy. There is nothing like it anyplace in the Middle East, or, so far as I know, in the world. It is certainly not a culture normally associated with terrorism.

In late September I met the SDF commander General Mazloum Kobani and other Syrian Kurdish leaders in Qamishli. They were wrestling with a simple question: Could they rely on the United States to deter an attack from Turkey or should they make the best possible deal with Damascus for their protection? After the 1991 Gulf War, the US imposed a safe area and no-fly zone over northern Iraq. This enabled the Iraqi Kurds to establish the Kurdistan Regional Government in 1992, which after the 2003 US invasion of Iraq became a de facto independent Kurdish state. It was a tempting model for the Syrian Kurds—but only if the US stayed.

Their only other option was to negotiate with Assad. But here too the Kurds faced a dilemma. Trump administration diplomats have insisted that the US goal in Syria was not just to defeat ISIS but to contain Iran’s regional ambitions and, in particular, to impede its access overland to its proxies in Shia-controlled Iraq and Syria all the way to the Hezbollah-controlled parts of Lebanon. Since the SDF controlled one third of Syria, it could help the US counter Iran’s ambitions. Serious negotiations with Damascus, however, could undermine US support, which made the Kurds reluctant to pursue them. But it was also clear that Trump did not share his officials’ view that the Kurds were essential in thwarting Iran. At the end of 2018, he tweeted (after a phone conversation with Erdoğan) that all US troops would be out of Syria in a month. While this was eventually walked back (after the resignations of Defense Secretary James Mattis and anti-ISIS envoy Brett McGurk), the question of what Trump would do hung over my conversations with the Kurds.

Still, Kurdish leaders were guardedly optimistic about US support. Trump envoy James Jeffrey had just negotiated a deal between Turkey and the Kurds in which they would withdraw their soldiers and heavy weapons from a “safe zone” along the Turkish border that the US and Turkey would jointly patrol. But there would be no permanent Turkish presence in northeast Syria.

Thus it seemed as if the Kurds could count on a continued American presence at least until the next US elections. As part of the deal, they agreed to fill in their trenches along the Turkish border. When I traveled to my meetings—all within sight of the border because that is where the people live—I could see miles of trenches filled with dirt. General Mazloum might have questioned why Turkey was so insistent that the SDF destroy trenches, which are purely defensive. But he trusted Jeffrey and the United States—for no doubt the last time.

On October 11, two days after Turkish forces crossed the border, Mazloum summoned a US diplomat to his headquarters and demanded to know what the US would do to stop Turkey. The American explained that he would need to consult and pleaded for time to get an answer. Mazloum dismissed him.

Russia did not need much time. Two days after Trump’s green light, Russian foreign minister Sergei Lavrov met in Erbil with KRG president Nechirvan Barzani, who asked him to help facilitate a security deal between the Syrian Kurds and Assad. Two days later, the Russians had one. The Syrian army would move to positions along the border between northeast Syria and Turkey. The SDF would be abolished as a separate military force and its units folded into the Syrian Army Fifth Corps under Russian control. The Syrian army and the Kurdish fighters would jointly drive Turkish forces from the border areas, including Afrin, a Kurdish enclave in northwest Syria that Turkey seized in 2017.

Once this was accomplished, Syria and the Kurds would negotiate Kurdish rights, including some level of autonomy, within a new Syrian constitution. When that is settled, the Kurdish administrative structures will disappear, and Kurdish leaders will take positions in the Syrian government. The withdrawal of US troops was a crucial part of the deal, and General Mazloum informed his US counterpart that they had to go. With US forces under fire from Turkey and some roads cut, a chaotic exit was already underway.

On my last day in Qamishli, I met with the leaders of about a dozen political parties, including those representing Christians and Arabs. One of the first questions came from a young woman who introduced herself as Hervin Khalaf, cochair of the newly formed Future Syria Party, which sought to bring Kurds, Christians, and Arabs together. Her question was similar to others that I had received during my trip. Can the Kurds, Arabs, and Christians count on the United States to support us? I explained that the United States did not have a normal person as president and so I simply didn’t know.

Four days after the start of Operation Peace Spring, Khalaf and her driver were ambushed on the main east–west highway in northeast Syria by Turkish-supported Islamists who killed the driver and then pulled her from the car. She was brutally beaten before being shot. They made a cell phone video of the killing and used Khalaf’s cell phone to call her mother and tell her what they had done. The State Department called the murder “troubling.”

After speaking to President Erdoğan on October 6, President Trump asserted that Turkey would be responsible for the 11,000 ISIS fighters and their nearly 100,000 family members that the SDF now guards. This is completely implausible. Many of the men are in prisons far from the Turkish zone of operations. Al-Hol, the largest of three camps holding ISIS women and children, is south of Hasaka, a city now partially in Syrian government hands. Should Turkish forces approach any of the prisons or camps, the Kurdish guards will not stay around to be captured or murdered, thus providing an opportunity for detainees to get away. Some already escaped from a prison in Qamishli and the Ain Issa Camp after Turkey shelled the two locations.

But the more important question is whether Turkey actually wants to detain the ISIS prisoners. During the peak of ISIS’s strength in 2013–2015, the US military estimated that two thousand foreign jihadis were crossing into Syria each month to join the caliphate, and the Russian Defense Ministry estimated that over 25,000 foreigners were fighting for ISIS at the beginning of 2016. Almost every one of these ISIS fighters got to Syria by way of Turkey. While there is no evidence of a single terrorist attack on Turkey from Kurdish-controlled Syria, Turkey was a conduit for terrorists flowing into Syria, including those fighting the Kurds and their American allies. Given the sophistication of Turkey’s intelligence service (as demonstrated, for example, by the information it gathered from inside Saudi Arabia’s Istanbul consulate about the murder of Jamal Khashoggi), it is impossible to believe that it did not know the identity or destination of the jihadis crossing the border. This raises the question of why Turkey would now detain terrorists it intentionally let into Syria.

A year ago, the Syrian Kurds asked Bernard Kouchner and me for recommendations on how to handle the two thousand foreign (i.e., neither Iraqi nor Syrian) fighters and 10,000 foreign women and children they had detained. While constituting just 20 percent of the captured fighters and family members, the foreigners are the most radical ISIS adherents. Foreign women, unlike the Syrian and Iraqi family members of ISIS fighters, almost all chose to go to Syria to join the terrorist group, and many participated in the enslavement of Yazidi girls and the grooming of suicide bombers.

The two thousand foreign men are going nowhere. The Kurds say they have no authority to conduct trials of foreigners and that either their home countries should take them back or an international tribunal should try them. With few exceptions, countries don’t want to repatriate their citizens, since they remain dangerous, but it is difficult to detain them legally. Far from the available evidence and witnesses, it is hard to prosecute those who committed murders, rapes, and kidnappings in Syria. In most European countries, the sentence for joining a terrorist organization (as opposed to committing acts of terrorism) is relatively brief—five to ten years in prison—and some European countries have to give credit for time served in Kurdish detention. Thus repatriated ISIS fighters could be on the street rather quickly after their return.

International tribunals have historically been used to try a handful of major perpetrators. There is no support for a tribunal that would try thousands of terrorists, especially since the current arrangements work well for everyone: the fighters remain incarcerated far from their home countries, and the Kurds cannot be blamed for holding them without trial. This situation cannot continue indefinitely. Under the deal that Syria negotiated with the Kurds, the Syrian state will eventually take control of the prisons and camps. The adults will likely disappear into Assad’s prisons, or simply disappear.

Children—about six thousand of them—are the largest group of foreigners detained by the Kurds. Some were brought to Syria by their jihadi parents, but most were born there. Conditions for children in the camps are appalling. There are only minimal medical facilities and no real schooling. Sanitation is unspeakable. But the greatest danger to the children comes, in many cases, from their own mothers.

In September I visited two of the three main camps, al-Hol Camp and Roj Camp, which is not far from where the Iraqi and Turkish borders meet. The most radical women have taken over al-Hol Camp, enforcing a strict ISIS dress code and mandatory Koranic instruction. They burn down the tents of families they consider insufficiently fanatical and have knifed to death several young women who didn’t wear the full black hijab and veil. The annex where the foreign families live is so dangerous that the camp administration was reluctant for us to visit, even in an armored car. Roj Camp is somewhat better. The Kurdish camp administration has successfully banned veils and the wearing of only black clothes, and it is possible to walk around with armed escorts. In both places, radical women are indoctrinating children with ISIS ideology.

Human rights groups and humanitarian organizations recognize the problem of children growing up radicalized but resist the logical solution: removing them from the camps and, if necessary, from their mothers. Instead, they have waited for countries to repatriate mothers and children together, which is not going to happen. One human rights advocate told me that what I described—a choice between taking children from their mothers or leaving them in an environment where they will grow up radicalized (and possibly never get out of detention)—as a Sophie’s choice. Sophie, of course, made a choice, which the humanitarian organizations decline to do.

The time for a choice may now have passed. The Turkish invasion has made the camps inaccessible to humanitarian organizations. Assad’s record does not suggest that his government will be concerned about keeping mothers with their children, or indeed concerned at all about the children.

Faced with a firestorm of Republican criticism, Trump decided to act against Turkey. On October 14, saying that “Turkey’s action is precipitating a humanitarian crisis and setting conditions for possible war crimes,” he imposed sanctions on three Turkish ministers and raised tariffs on Turkish steel. He also called General Mazloum and told him that he was surrounded by people who loved the Kurds more than their own country, and otherwise rambled. Mazloum wondered about the point of the call.

At Trump’s direction, Vice President Mike Pence and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo met Erdoğan in Ankara on October 17. They were meant to advance a tough Trump line, as expressed in a strikingly undiplomatic letter that Trump wrote to Erdoğan urging a deal and ending with the admonition: “Don’t be a tough guy. Don’t be a fool!” Pence and Pompeo made a deal: one that gave Erdoğan everything substantive that he wanted, including a US endorsement of the Turkish invasion and a promise to lift sanctions. In exchange, Turkey agreed to suspend military operations for 120 hours.

In the eight days prior to the meeting, Turkish forces—or more precisely Syrian proxies comprised of Islamists, ordinary criminals, and $100-a-month mercenaries—expelled 200,000 civilians from the border areas. In a tweet, Trump applauded this ethnic cleansing, saying it was good news that the Kurds were resettling south of the Turkish safe zone. But many in the villages between Tal Abyad and Ras al-Ain are not Kurds but Syriacs, Chaldeans, and Armenians. One wonders whether Pence—the self-styled protector of Christians—realized he had negotiated the ethnic cleansing of Christians.

On the final day of the cease-fire, the Turkish president met with Vladimir Putin in Sochi. After six hours of talks, the two leaders agreed that Turkey’s proxies would remain between Tal Abyad and Ras al-Ain, that Kurdish forces would have six days to withdraw twenty miles from the border, and that Russian military police and Syrian border guards would enter the Kurdish-held border zone starting at noon on October 23. The two leaders must have shared a good laugh over one point in their agreement—that Russian and Turkish troops would jointly patrol a zone along the border six miles deep, since Russia was now assuming the exact responsibility proposed for US troops in the deal that Trump envoy Jeffrey had sold to the Kurds just three weeks before.

The destruction of the US position in Syria was complete. Putin, Erdoğan, and Trump had provided President Assad with his biggest victory in the nearly nine-year civil war: the recovery of one third of his country without firing a single shot. In 1974, Anwar Sadat switched Egypt, then the most important Arab country, from the Soviet to the American side, leading to nearly fifty years of US dominance in the Middle East. With America in retreat, Russia has now emerged as a principal regional power broker. If Putin can pull Turkey away from the US alliance—and Erdoğan is certainly acting as if Russia is Turkey’s most important partner—he will have accomplished something that none of his Soviet predecessors dreamed possible: the partial breakup of NATO. Trump, a longtime NATO basher and Russophile, will have made this possible, intentionally or not.

As if to rub it in, journalists covering Russian troops moving into US bases in Syria broadcast pictures of the half-eaten meals and stocked refrigerators left behind as US soldiers made their hasty exit. On their way out, the soldiers saw signs thanking America but denouncing Donald Trump as a traitor. In Qamishli, however, angry Kurds pelted US armored vehicles with potatoes and stones.

For the parties in the region, there is one clear lesson from all this: Russia and Iran stick by their allies; the United States does not. When Assad teetered on the brink of collapse in 2015, Russia and Iran stepped in to save him. When the Kurds defeated ISIS and were well positioned to thwart Iran’s regional dominance, Trump abandoned them, even though the costs of a continued US presence were minimal. As Tehran prepares to mark the fortieth anniversary of the start of the hostage crisis, this latest American humiliation must be particularly sweet.

The future of the Syrian Kurds depends on how events now unfold. Although the Syrian army and state institutions are now returning to the northeast, Damascus does not have the military or other resources to fully control the area. With 70,000 men and women under arms, the SDF remains a potent Kurdish-led military force even if the Syrian flag is added to their shoulder patches. And it is not clear that the Syrian government can—or wants to—dismantle the political institutions created by the NES, at least in the short term.

The SDF was, of course, not a party to either the Putin-Erdoğan or the Pence-Erdoğan agreements. While it has no choice but to accept the protection of Russia and the Syrian government, this does not mean that it will abandon the places right along the border where almost all Syrian Kurds live. If Erdoğan resumes his war, the ethnic cleansing could be enormous.

—October 24, 2019

This Issue

November 21, 2019

The Defeat of General Mattis

The Muse at Her Easel

Lessons in Survival

-

*

My association with the Iraqi Kurds goes back to 1987, when—on a trip to northern Iraq as a staffer for the Senate Foreign Relations Committee—I came across the systematic destruction of Kurdish villages, now considered to be the beginning of the Kurdish genocide. As a private citizen in the first decade of this century, I was an informal adviser to the Kurds as they negotiated de facto independence in the Iraqi constitution and, working with a Norwegian oil company, helped establish the Kurdistan oil industry that today provides the economic basis for independence. Most recently, I was an informal adviser to the KRG leading up to the 2017 independence referendum. ↩