There are two stories, one might say, being told at the American Folk Art Museum’s current show “Memory Palaces: Inside the Collection of Audrey B. Heckler.” The first and more clear-cut is that the exhibition gives us a chance to see what must be one of the most discerning and wide-ranging collections of self-taught, or outsider, art in this country. There are top-notch works here by artists of varying degrees of recognition, many of whom were active in the middle and later years of the last century. Some, including Carlo Zinelli, William Hawkins, Adolf Wölfli, Thornton Dial, and Madge Gill, are known to people who follow this art but are not quite household names. There are strong works here as well by artists—such as Christine Sefolosha, Malcolm McKesson, and Edmund Monsiel—whose pictures may come as a welcome surprise to nearly everybody. And there are fine pieces by Bill Traylor and James Castle, and extraordinary ones by Martín Ramírez, who are all becoming widely known.

For some museumgoers, the Mexican-American artist Ramírez, whose sometimes impressively large drawings are generally made up of parallel lines that form mountains and railway tracks, horseback riders and theater-like settings—linear realms that suggest both Art Deco ornamentation and imprisoning situations—may be as beckoning a figure as any mainstream artist of the past few decades. His renown is such that a few years ago the US Postal Service made him the subject of stamps showing a number of his images. With his immediately accessible pictures, Traylor’s audience is probably broader. In his deceptively simple silhouette drawings, based on memories and experiences of his native rural Alabama, fierce animals, adamantly striding men in high hats, and the occasionally wobbly fellow with his bottle have the presence of characters in an epic told entirely in hieroglyphics.

The second and somewhat buried story in “Memory Palaces”—which was preceded by a volume entitled The Hidden Art: 20th- and 21st-Century Self-Taught Artists from the Audrey B. Heckler Collection (2017)—revolves around the nature of the artists we are seeing. They come from notably different places, both geographically and in the kind of work they make. Put simply, the ever-expanding realm of self-taught or outsider artists (or, to use a recently proposed term, outliers), who have been increasingly of interest to art historians, museum curators, and collectors, breaks down into roughly two approaches. On the one hand, there are a number of American and largely southern figures whose pictures and sculptures often appear to have been made quickly and spontaneously. A fair number of these artists became known beginning with an influential 1982 exhibition at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington called “Black Folk Art in America, 1930–1980.”

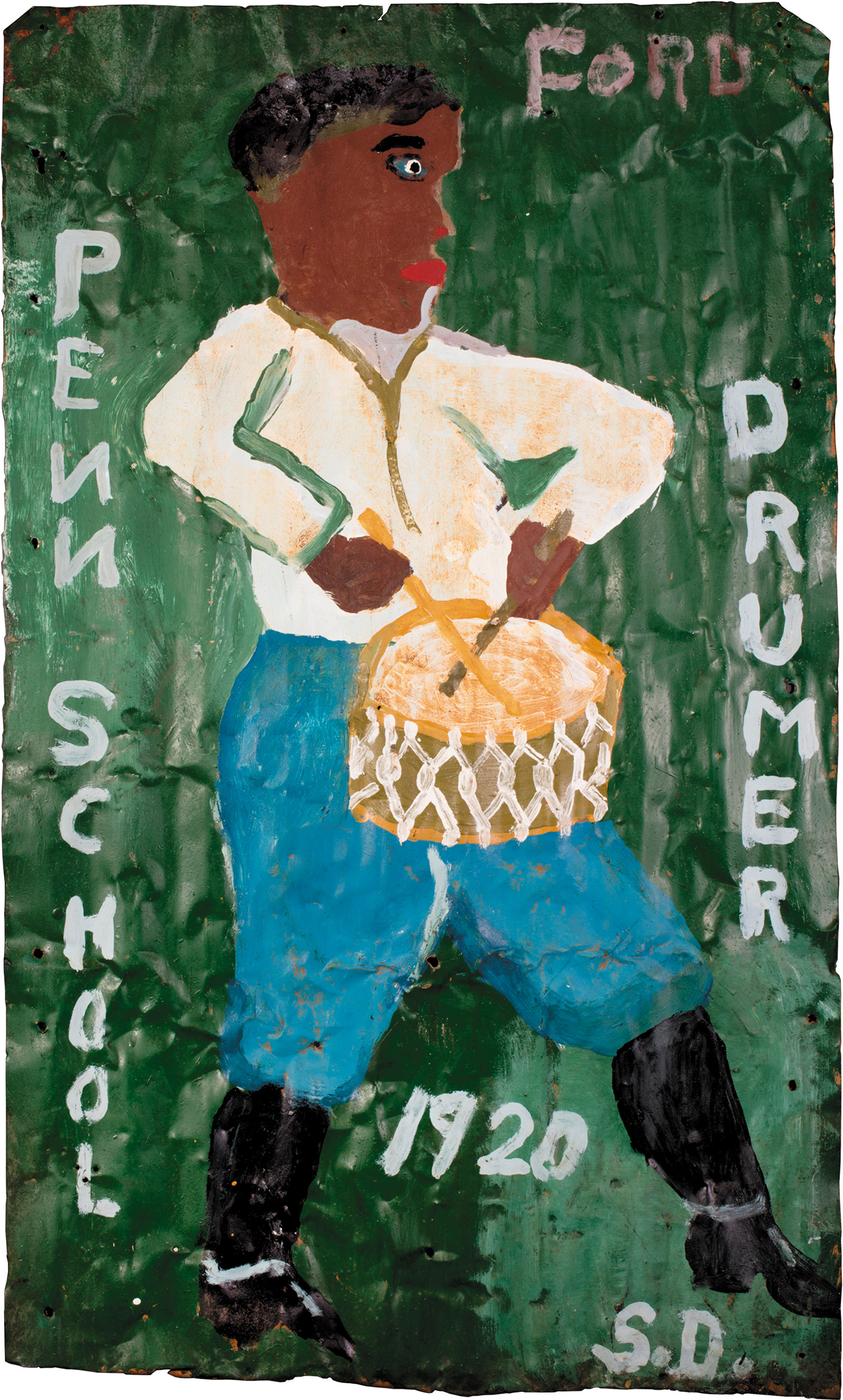

In their paintings and painted objects, people and animals tend to be brushy and loosely formed, and their works, as in a touching and oddly beautiful painting in the current show by the South Carolinian Sam Doyle of a boy stepping out while playing a drum, often convey a splashy energy. Doyle’s Penn School Drumer, dating from around 1970, is painted on a slightly beat-up sheet of tin, and it is a characteristic of these artists to employ any old leftover material. Tin was a favorite, at least with Doyle and David Butler, who is also in Heckler’s collection—he made whirligigs and flat sculptures in vibrant colors—because they liked to place whatever they made in their yards.

For a number of these creators, there was little difference between making art and proclaiming their Christian faith. Sister Gertrude Morgan, for instance, is seen in the show in a rousing work on paper called The Greater New Jerusalem, which records, in her appealingly urgent, childlike hand, what she believed was her mystic marriage to Christ. It shows the bride and groom before Jerusalem, which here resembles an enormous apartment building, with every unit open for us to see its furnishings and inhabitants. The New Orleans–based Morgan was a full-time preacher, as was Howard Finster, whose thousands of works are painted on whatever was at hand, including sneakers. But even if the artists were not preachers, their pictures and sculptural assemblages were meant to be understood by, even to speak for, the communities they were part of. And not all these artists were black. Reverend Finster was not.

On the other hand, there is a range of artists who are often European and frequently, unlike their counterparts from the American South, did not share a community ethos. Whether their pictures were made when, diagnosed with schizophrenia, they were confined to psychiatric hospitals (as happened with Zinelli, Ramírez, Wölfli, and the Russian Eugen Gabritschevsky, who is also represented in the show), or they led reclusive existences (which was the case with the Chicagoan Henry Darger, whose work is on view as well), or they lived entirely in their families’ homes (as did the Idaho-based Castle), their respective bodies of pictures seem indebted to their finding safe and removed settings in which to work.

Advertisement

There are huge differences among the figures in this second group. Castle was a kind of sketcher, in washy, pale-gray tones and a halting style, of his everyday surroundings. There often seems to be a fine drizzle in the air, even when his scene is indoors. But many of these others made pictures that are more like so many novel, highly personal languages, with ambiguous repeating forms and, in Gabritschevsky’s case, wild shifts of imagery. A near-common denominator among these artists is that they generally did not make paintings in oil—and it might be said of both branches of self-taught or outsider artists that they rarely present any form volumetrically or show the effect of light. Deriving their art from what they saw inwardly and wanting to get their visions down without fussing with materials, our second group of artists primarily drew on paper, and when their visions demanded it they found ways to extend the sheet they started with. Ramírez repeatedly made an image that many of these creators might have responded to: a person at a table, drawing.

Few of the figures in this second group were religious in their concerns, although a number of them (and not necessarily the most involving) seem as if they might have worked in a trance. That is said specifically about the Japanese artist Hiroyuki Doi, now in his early seventies and for much of his life a master chef. His large and untitled ink drawing here, a picture that seems to present molecular energy in itself (and that slightly recalls the work of the contemporary painter Terry Winters), has been made entirely from the accumulation of an uncountable number of tiny circles.

At the Folk Art Museum’s show, there is no clear demarcation between the two kinds of artists. Although the display is sensitive and balanced in itself, the works are somewhat run together, undoubtedly to indicate that they are of equal interest to Audrey Heckler. Photographs of her New York City home in The Hidden Art indicate exactly that. Viewers coming to the exhibition without having seen much self-taught or outsider art may not be immediately aware of any larger distinction. But surely it is hard to hold together in your mind Doyle’s Penn School Drumer and Doi’s reverie on circles—or the large and boldly painted pictures by William Hawkins of the Last Supper or of a Wendy’s hamburger outlet and Madge Gill’s drawings in ink of women (they all have the same face) embedded in a profusion of interlocking curly lines, shapes, words, and checkerboard patterns.

Heckler’s collection is not the only one to bring together figures from what might be called the public and private sectors of self-taught art. In a significant exhibition in 2013 at the Philadelphia Museum of Art entitled “‘Great and Mighty Things’: Outsider Art from the Jill and Sheldon Bonovitz Collection,” artists of the former group, including Doyle, Hawkins, and Sister Gertrude Morgan, were seen with artists of the latter group such as Ramírez and George Widener, who is now in his fifties and makes mind-bogglingly abstruse if also rhythmic drawings based on numerical progressions and coincidences. But Philadelphia’s exhibition was so heavily weighted in favor of American and southern artists that their concerns seemed to sum up outsider art, while Heckler’s collection is far more balanced.

The balance, though, doesn’t make things clearer. When Sam Doyle, with his lovely bluntness and singing color, is shown with Martín Ramírez, whose wish to render everything in its skeletal, framework form seems to combine the thinking of a mathematician, an architect, and a poet, motivations are smudged. Neither artist’s experience talks to the other’s. In her sharp and comprehensive introduction to The Hidden Art, Jane Kallir acknowledges, in passing, this bump at the center of self-taught art. But she brushes it off, as possibly others do, writing that while the artists, “hailing from such disparate locations as the Alabama streets and a Swiss mental institution,” have “nothing intrinsic in common,” the collection holds together because of “Heckler’s taste, her love of color, and her appreciation of elaborate patterns.”

Advertisement

If there is a larger message in the Folk Art Museum’s show, it might be that our thoughts about self-taught or outsider art are, happily, far from settled. For me, the most powerful works in the exhibition have little to do with one another, which makes good outsider sense. Christine Sefolosha’s Birth Giving, an intricately designed, five-foot-high oil painting from 1993 in an array of rich and delectable colors, is certainly a highlight. It is difficult to tear yourself away from this image of creatures and spirits of all varieties and sizes—birds, people, ghouls, fish, antlered beasts, face masks, vaginal shapes, wraiths, horses—pouring forth. It can remind a viewer of pictures from decades ago by Surrealist artists attempting to show their crowded unconscious, but this hardly dampens the force of the Swiss artist’s canvas.

Sefolosha comes from out of the blue. William Hawkins, in contrast (he died in 1990), is for some American viewers an almost familiar figure. Although he was not in the Corcoran’s black folk artists show, he began to be seen in commercial galleries soon thereafter, and just last year he was the subject of a large retrospective that toured the country. He was almost the definition of a public artist. He prominently placed his name and that he was born in “KY” on July 27, 1895, at the base of all of his pictures, which are typically three or four feet wide and can be six feet on a side. His paintings, which are often of city buildings that he knew or of hearty, lunging animals, convey the same unalloyed energy that is felt in each of his confident, broad, splattering brushstrokes.

But looking at the untitled 1986 picture in Heckler’s collection of the Last Supper, one is absorbed primarily by how unexpected Hawkins can be in his color choices and the way he shows the inner space of a scene, and by his blithely making Christ resemble a character out of a Velázquez painting. Going through the catalog of his recent retrospective, entitled “William L. Hawkins: An Imaginative Geography,” we find an artist, quite like Stuart Davis and Elizabeth Murray, who provides one engaging demonstration after another of how to construct a picture and the liberties that can be taken in doing so. It may be enough to say that in his many versions of the Last Supper, most illustrated in the recent retrospective catalog, he never seems repetitious.

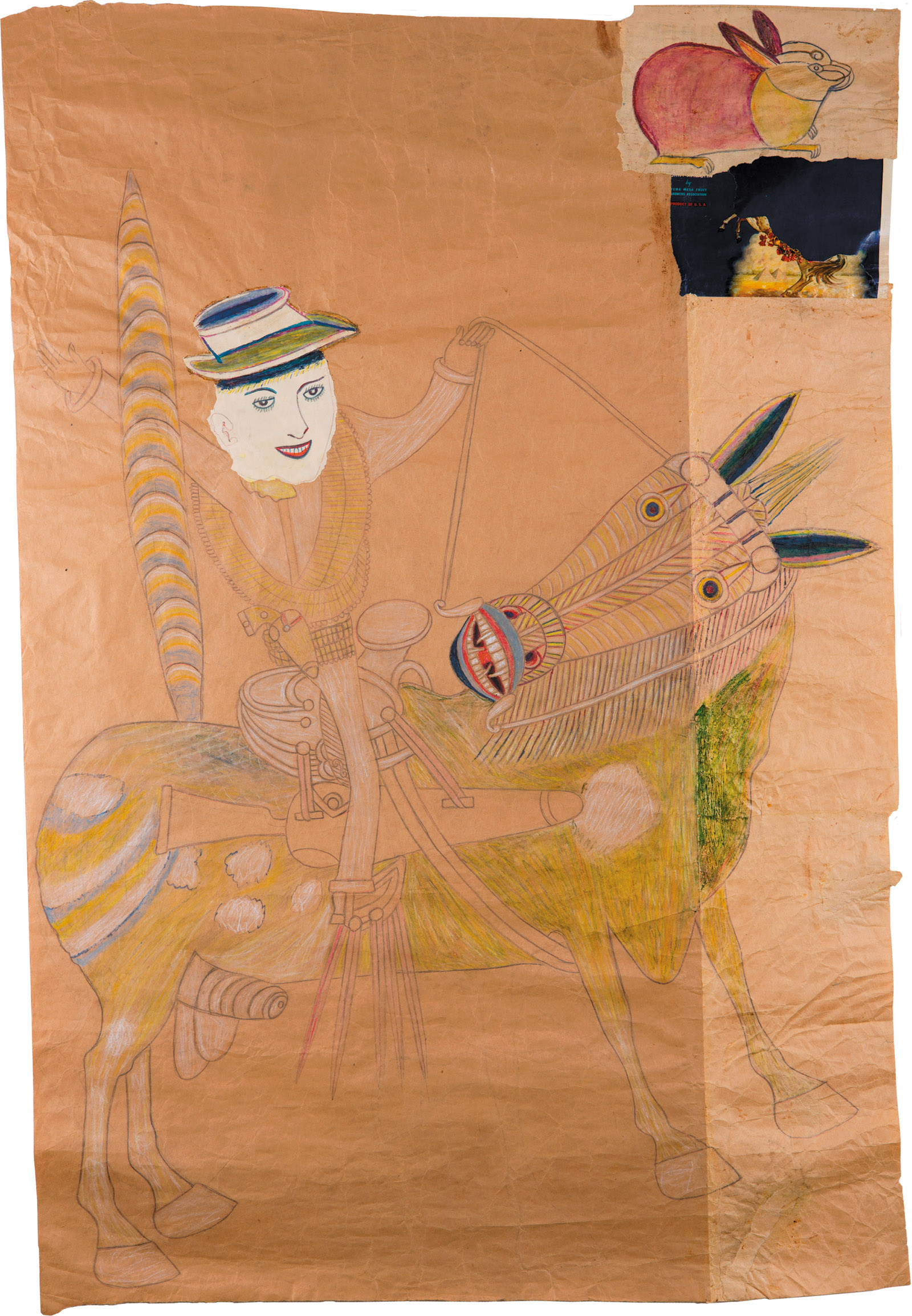

If there are gradations among geniuses, Ramírez might have been more of one than Hawkins. Heckler’s collection of works by the artist, who died in 1963, includes a number of winning examples, but an untitled, nearly four-foot-high drawing from around 1950 of a man on a horse who has a white face and a somewhat naturalistic appearance is remarkably fresh. It is striking not merely because it was absent from the Ramírez retrospective that the Folk Art Museum did in 2007 but because it seems to present a new strand in our understanding of the artist. With his train tracks and highways running through mountains, Ramírez might seem at first like a landscapist, whether of his native Mexico or the California where he came to live for much of his life. But his rolling terrains, marked by a heightened sense of both structure and emptiness, are essentially psychological in tone, and it makes sense that he continuously brought people into his images.

Many of them are caballeros, but there is also that fellow seated at a table, drawing, and some of Ramírez’s largest pictures are of a benevolent Madonna. He made all of their faces in the same graphic way he drew his trains and roadways. But he clearly wanted to go further in bringing a human presence into his world, because he sometimes created the faces of figures by pasting on pictures cut from magazines or newspapers. They seem to have been only of women. In the man’s face in the picture in Heckler’s collection, though—a face fashioned from simply a coat of plain white gouache, to which a few facial features have been deftly drawn and collaged on—he went way beyond those attempts.

Wearing a hip, two-toned, small-brim fedora, this figure is hardly another folklore caballero. He is a contemporary person, one whose smiling face is at once friendly, masklike, and a little unnerving. Ramírez’s picture as a whole, with its radically informal placement of drawn and collaged parts and areas of near empty space, is dazzling. But the charge of the work comes from the horseman’s character. It reveals that, powerful and replete as Ramírez’s work is, he was still pursuing, in his thinking, new roads.

This Issue

December 5, 2019

Against Economics

‘I Just Look, and Paint’

Megalo-MoMA