The title work in Vija Celmins’s bewitching retrospective, To Fix the Image in Memory I–XI (1977–1982), is a loose collection of small stones like those found on windowsills and porches the world over, the kinds of things people pick up out of mild interest and then never quite get rid of. Because there is nothing remarkable about any of the stones beyond the fact that they are sitting on a plinth in a museum, it takes a moment to figure out why exactly they feel so strange. And then you see it: each rock has a twin of the same size and shape, bearing the same black specks and tan freckles in exactly the same places. Eleven of the twenty-two stones were picked up by the artist while walking in the desert; the other eleven are cast bronze, painted to replicate each random detail of their models. In a nod to Duchamp, Celmins calls them “readymades” and “mades.”

The piece is a trick, but also something more. To solve the puzzle—can you spot the imitation?—you have to apply the same intense concentration the artist did. Human brains are good at recognizing faces and symbols and certain types of motion, but they aren’t built to recall the specific arrangement of thousands of individual specks on a rock. The title itself is a tease: To Fix the Image in Memory lures us into committing energy and interest to something we are fated to forget. But the artwork leaves us with a lasting sense of possibility, an awareness of the largely unnoticed richness of the world.

Celmins has been an admired artist for more than fifty years, and for most of that time critics have struggled to explain the elusive poignancy and staying power of her work. In an art world that rewards noisy assertion and the avid annexation of wall space, her work is thoughtful, modest in scale, mostly black-and-white. And while much contemporary art prides itself on being difficult, even opaque, Celmins’s paintings and drawings of night skies and oceans are eye-pleasing and generous in a way that keeps them broadly appealing, even as they contend with weighty questions about the mechanics and consequences of representation. All this makes her work hard to encompass in the current language of art. Looking at her pairings of apparently identical rocks, the word that floats to mind is not “simulacrum” but “sublime.”

This ambitious retrospective, on view at the Met Breuer through January 12, charts her career through some 120 paintings, drawings, prints, and sculptures arrayed over two floors of the museum. (Organized by Gary Garrels of SFMoMA and Ian Alteveer at the Met, it was previously seen in San Francisco and Toronto.) The beautifully produced catalog provides a thorough overview of Celmins’s life and artistic development—her early childhood in Latvia when it was less a nation-state than a geopolitical chew toy yanked between the Soviet Union and the Third Reich; subsequent years as a refugee when her family fled to Germany, arriving during the final onslaught of Allied bombing; her later upbringing and education in Indiana; a critical few weeks at the Yale Summer School of Art and Music in 1961 that convinced her to be a painter; her decades as an artist in Los Angeles in the 1960s and 1970s, and in New York ever since. One of the catalog highlights is a compilation of interviews with the artist; these are revealing as much for what is not said as for what is. Celmins discusses life events and working methods with clarity, charm, and humor. She acknowledges other artists who have had an influence on her: Willem de Kooning for his redefining of what you could do in a two-dimensional space; Giorgio Morandi for what you could do with a small space and a reduced palette. But on larger metaphysical questions she is mum. “I don’t mind talking about making work,” she told the sculptor Ken Price. “What it is supposed to mean is what I can’t talk about.”

Two years younger than Frank Stella and two years older than Chuck Close, Celmins came of age during Abstract Expressionism’s victory lap. As a student she was excited by the idea of painting that pointed to itself for content rather than to some external storyline, but like many of her peers, she grew uncomfortable with the AbEx equation of visual structure and emotional self-exposure. When every shape and gesture is perceived as a song of inner emotional truth, it can be hard to make a casual mark without feeling like a fraud. As a graduate student at UCLA, she concluded that she was “thinking too much…and inventing too much, and it seemed to mean nothing.” To find her way out of this corner, she began painting things that were kicking around in her studio—an electric fan, a hotplate, an opened envelope, food.

Advertisement

It was 1964, and in New York Claes Oldenburg was sculpting sandwiches and Andy Warhol was exhibiting Brillo Boxes, but Celmins was not aiming to shine a light on commodity culture; she “was trying to get back to some kind of basic thing where I just look, and paint.” Working swiftly, she painted her studio flotsam with a Magritte-like deadpan, setting each object within the sort of ambiguous, umbrous space that Velázquez wrapped around his Spanish grandees. Several of these still lifes open the retrospective, and the effect is of a down-at-the-heels, postindustrial iteration of the enchanted housewares in Beauty and the Beast: a double gooseneck lamp seems to be rolling its eye-bulbs in exasperation; the maw of a space heater glows like the Hellmouth in a medieval manuscript (see below). A ghostly portable television, painted in thin grays, is particularly unsettling, its screen lit with a cloud-dappled sky through which chunks of an exploded plane arc downward. A little brooding makes it clear that this must be a concoction: televisions may sit still for their portraits, but broadcasts do not. In fact, the plane came from an entirely different source—a black-and-white news photo that Celmins had clipped and chosen to replicate on the screen.

For Celmins, this was a small invention with large implications. Using an existing flat image as the basis of a new flat image offered an end run around the problem of composition (that is, of people reading unintended content into compositional choices), and it also addressed the essential conundrum of pictures. In “redescribing”—her verb of choice—a prior image, she could simultaneously depict something that was there (the clipping) and was not there (the plane).

Almost everything that follows in Celmins’s career builds on this discovery: flat works that redescribe preexisting flat things, mostly photographs; sculptures that redescribe preexisting three-dimensional things, like stones. The fifth-floor galleries at the Met Breuer survey Celmins’s early efforts to work out what to do with this discovery. She made muted color paintings from photographs she took while driving on LA freeways, and Pop-Surrealist sculptures from childhood belongings—pink erasers the size of sofa cushions, a pencil the length of a person. A group of somber grisaille paintings recreated printed images of explosions, fires, and airplanes. She calls these the “war things,” and obvious parallels can be drawn between them and the photo-based airplane paintings of Gerhard Richter, another child of the same war. For both artists, news coverage of the escalating conflict in Vietnam was an impersonal prompt that connected to personal experience. As graduate students in two different hemispheres, they hit on the same tactic at the same time and for many of the same reasons—a desire to escape the implications of self-expression, a curiosity about the lies and truths of images, a love of gray. (Stylistically, Richter and Celmins went on to develop in different ways, though there are still intriguing attitudinal resonances.)

In 1968 Celmins stepped back from painting to concentrate on drawing. It was a way to distill further the range of decisions made in a given work: paper, pencil, stroke and intensity of line, source image. In one group of drawings from that year, she presents her sources as battered relics—paper or postcard, crumpled and torn, resting at the center of a silvery graphite ground. With their suave surfaces and faux shadows cast by faux paper, these have a certain kinship to the “ribbon word” drawings Ed Ruscha was making around the same time, and they also echo an older trompe l’oeil tradition of painted prints, from Sebastian Stoskopff in the seventeenth century to John Frederick Peto in the nineteenth. But the inherent cleverness of trompe l’oeil, its sense of an image delivered with a wink and a nudge, is absent from Celmins’s drawings, in part because everything they show is tragic: the Hindenburg, the remains of Hiroshima, another sky littered with pieces of falling plane. Yet the drawings are not particularly mournful. The events are sad, but they exist at a distance. While the depicted violence and loss can never be quite out of mind, they share that mental space with other things: the rigorous beauty of the surface, and one’s consciousness of the care and precision—devotion, even—that went into their making.

Speaking with Chuck Close in the early 1990s, Celmins explained:

What I want to tell you is it wasn’t a system. My working from photographs was really an affection for certain little areas in the photographs that I carried around with me and that I reexamined all the time.

For all the cerebral elegance of Celmins’s art, at its heart is a candid delight in images. The nature of these photographs changed, however, in the late 1960s. Historical events, machines, and childhood associations gave way to pieces of nature. From here onward (it’s at this point that the show moves from the Met Breuer’s fifth floor to the fourth), her subjects would be “impossible images…nonspecific, too big, spaces unbound.”

Advertisement

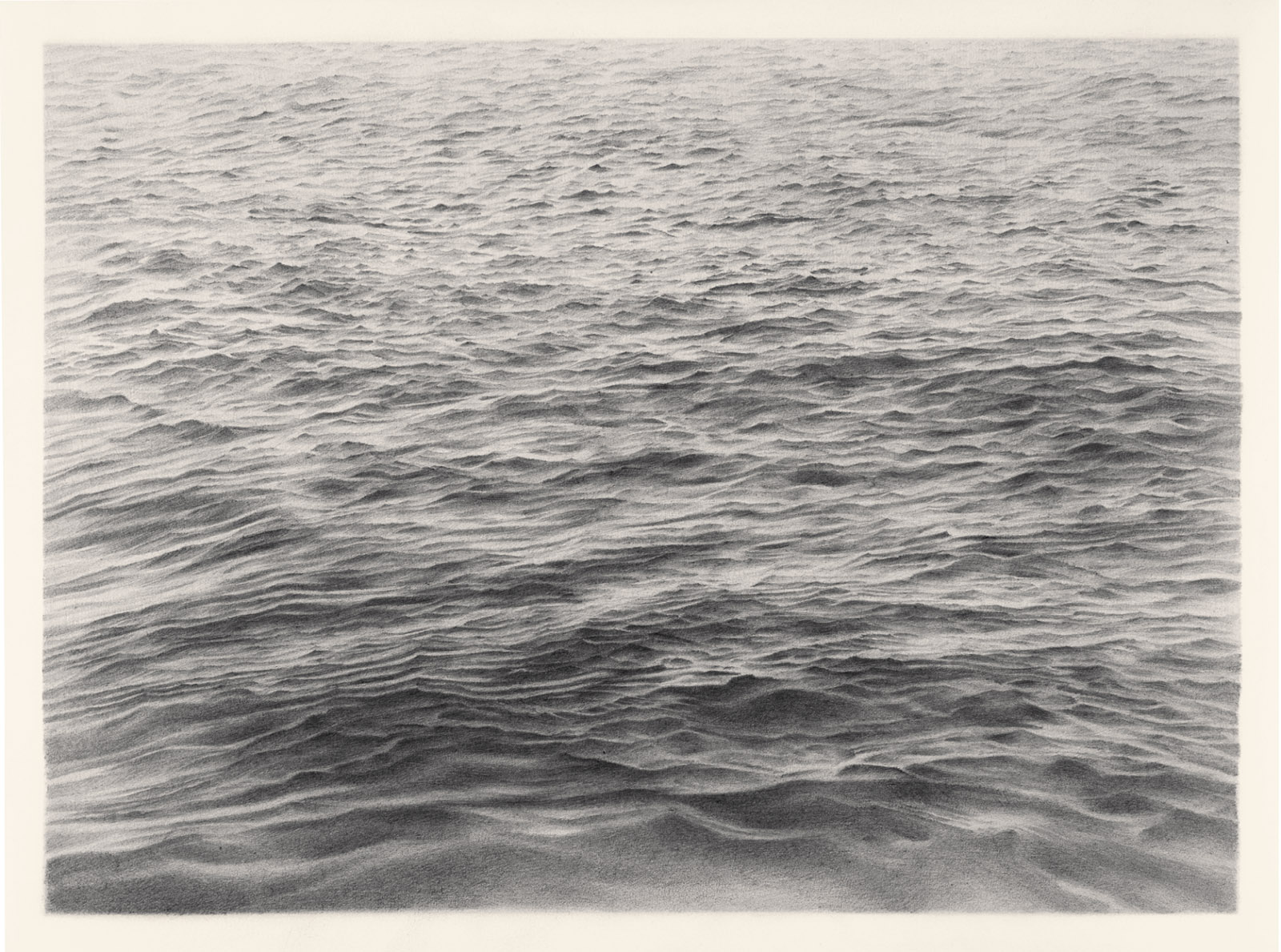

The ocean drawings she began making in 1968 show nothing but active water—choppy, dimpled, swelling, twitchy. There is no horizon, no meeting between one kind of thing and another, except at the edges where the pencil cedes its territory, stroke by stroke, to blank paper. Thirteen of these drawings, created over the course of two decades, wrap around one gallery in the exhibition. Even from a distance they are distinct in size, character, and visual weather—shimmering with tight, hard pencil strokes, or heavy with softer marks, or glowing hazily with smooth gradients. Up close, you see that every swell, curl, and cranny has been given its individual due. There are no schematic waves, nothing is generalized, and no part is prioritized over any other. The complexity of the photographs they are based on (taken from Venice Pier while walking her dog) was such that, for the first time, she had to use a grid to avoid getting lost. She worked methodically, section by section, from lower right to upper left. She never used an eraser.

These drawings are astonishing feats of attentiveness, as are the desert floors that follow, in which every irregular pebble and clump of dirt receives equal care. The deserts, like the oceans, come in various sizes, which changes their character in unpredictable ways. Then there are the Night Sky paintings, drawings, and prints, probably the best known of her works, in which she fixes the position, diameter, and halation of every star in a specific astronomic sector.

The subject should be a cliché, like sunset on a beach, one of those entrancing natural spectacles inexorably cheapened by art. But just as her oceans—still and colorless—don’t actually recall the appearance of moving water, the night skies, with no grounding ridges of mountains or treetops, don’t look much like what we see when we look up, unless we are in Chile’s Atacama Desert. They are captivating because, for whatever evolutionary reason, we are suckers for small lights scattered in darkness, and also because the logic of that scattering isn’t entirely what we expect. Before photography, subjects like oceans and heavens had to be pictured through reduction or approximation—you got celestial maps, or you got Starry Night—two different strategies for giving a human order to things manifestly not designed by humans. Celmins does something else: forgoing all shortcuts, formulas, and emotional editorializing, she adheres to what is—and that is strange.

These large structures can entice from afar, but there is a second strangeness at play in Celmins’s art—a not-quite-penetrable entanglement of marks and tangible surface that brings people to stand with their noses centimeters from the glass or canvas. (It cannot be fun to be a guard at this show.) And this propinquity results in a doubling of perception: the ocean is churning wavelets and also mineral specks stuck on fibers. The dark between the stars isn’t just empty space, it is graphite, pressed and polished; or it is light-sucking swaths of etching ink; or it is layer upon layer of alkyd oil paint, sanded and reapplied until it resembles unpolished jet or home-cooked Bakelite. (This flip-flop between matter and illusion is particularly insistent in Celmins’s woodcuts and recent intaglio prints, where the image arises from a concatenation of distinct strokes or flicks laid into wood or metal. These were unfortunately absent from the retrospective, though concurrent shows of Celmins’s prints at the Matthew Marks and Senior and Shopmaker galleries in New York helped fill the lacuna.)

Similarly, Celmins calls attention to the edge in each of her paintings and works on paper because it forms the handshake, or head butt, between material reality and visual illusion. In the night skies, for example, the Bakelite ebbs away as the canvas approaches the stretcher, leaving a clearly visible rim of schmutzy fabric. I can imagine some people find this quirk disappointing; it’s natural to want the mirage to go on and on, and if it has to end, to wish it would do so swiftly, in a way that keeps that magical otherness intact. Instead, Celmins wants to emphasize the point where “one breaks the illusion of continuous space and sees the making process and that the work is really a fiction.”

Because Celmins’s oceans and desert floors and night skies are so seductive, it is easy to miss how radical they are. Without any fuss, they simply sidestep centuries of conviction about how good art operates and what it looks like. These convictions are still, for the most part, rooted in the visual program of sixteenth-century Italy, with its centralized compositions, its viewer-flattering “just for you” framing of events, its love of big people and small landscapes. For five hundred years, the job of art has been to winnow meaning from the buzzing particularities that make up the world; to clarify, to abstract, to control. Techniques that lend themselves too willingly to small detail—engraving, embroidery, goldsmithing—are dismissed as “minor” arts, and interest in small irregular truths is treated as a sign of naiveté, weakness, or (almost a synonym) effeminacy. Michelangelo reportedly said that detail-rich Flemish painting would “appeal to women”—it wasn’t a compliment.

Thus Raphael trumped Dürer, Rembrandt trumped Vermeer, and dull late John Singleton Copley trumped dazzling early Copley. Sir Joshua Reynolds (largely to blame for Copley’s decline, but no matter) was simply affirming accepted truth when he wrote that the beauty and grandeur of art consisted in surmounting “all singular forms, local customs, particularities, and details of every kind.” And even as the nineteenth- and twentieth-century avant-gardes set about aggravating their local status quos, the unquestioned primacy of large-muscle groups over fine-motor skills persisted. In a 1943 letter to The New York Times, Mark Rothko and Adolph Gottlieb wrote, “We favor the simple expression of the complex thought. We are for the large shape because it has the impact of the unequivocal.” Furthermore, “It is our function as artists to make the spectator see the world our way—not his way.”

In contrast, Celmins offers artworks with no focal point, no hierarchy, no instruction about this bit being more important than that bit. Perhaps the most visually splendid moment of the installation at the Met Breuer occurs at the entrance to the fourth floor, opposite the elevators, where half a dozen small ocean pictures of slightly different sizes and flavors of gray are ranged along a freestanding wall—they form one work, A Painting in Six Parts (1986–1987/2012–2016). Each is engrossing and distinct in character. They all derive from the same photograph, but this is perceived more as a subconscious rhythm than a cogent observation. (The Breuer’s bluestone floor slates, similar in size and tonality to the paintings, is a subtle optical boon.) On the perpendicular walls to either side hang two large Night Sky paintings, one with white stars shining in darkness, and the other in negative, with dark stars on white ground. The lesson is clear enough: there are endless ways to see the world.

Behind the wall with the six oceans, there is a selection of recent paintings that return to the depiction of individual objects rather than expanses of nature. One shows a copy of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, its cover splayed like a pinned butterfly; another the scruffy blue jacket of a Japanese book (also “redescribed” as an etching that formed the cover of Celmins’s book with Eliot Weinberger, The Stars).1 Two small and tender paintings detail the surfaces of a worm-eaten shell and the craquelure glaze of a vase. Finally, there are works in which she has taken antique school slates and, working with a furniture builder, remade them by hand, mimicking every arbitrary scratch and nick, in the manner of To Fix the Object in Memory.

It is tempting to say that this gallery brings the show full circle, back to the still lifes that kicked it off, but it’s less like a circle than a spider web (another subject she has treated repeatedly; see illustration on page 16). The new paintings connect to the earlier works along multiple axes: the school slates are linked to the ersatz stones, but also to the giant pencils and erasers; the pattern of fissures in the glaze of the vase echoes the desert earth; the creased book cover nods to the dinged postcards and torn clippings. While her early subjects spoke of human actions and inventions, her later ones of forces beyond human control, the new ones acknowledge the shared passage of time. What they portray is the accretion of events, some designed, some accidental, some built into the laws of physics.

Part of the problem in discussing Celmins in the terms of contemporary art is that the conundrums that most intrigue her are not, strictly speaking, contemporary. They have been with us a long time. When I look at Clouds (1968) or Falling Star (2016), the artists who most often come to mind worked earlier, before photography, when the game of illusionistic re-presentation of the world was at its apex of excitement and uncertainty. Like Velázquez, Celmins is a choreographer of double-reality, making the pictorial illusion and the material truth equally mesmerizing. One of the legacies of Italianate thinking about art, Svetlana Alpers has argued, is that it left us without a useful language for discussing images that don’t prefer human subjects or narratives (either explicitly or implicitly, as in the case of Abstract Expressionism’s emphasis on the experience of the artist). In a beautiful phrase, she described Vermeer’s View of Delft (circa 1660) as “neither ordered nor possessed, it is just there for the looking.” She might have been writing about a Celmins ocean.2

In so much recent art, the urge to say has preempted the willingness to see. Exhibitions and their accompanying statements often demonstrate continued allegiance to the idea that the job of the artist is indeed to “make the spectator see the world” this way or that. (In this respect, contemporary art, despite its many claims of “intervening” in systems of oppression, often mimics rather than disrupts the worst impulses of the world at large.) “To Fix the Image in Memory” is an important show for many reasons, but mainly because it puts looking before speaking. It is enjoyable because Celmins’s affection for images is contagious, and it is critical because her affection does not imply gullibility—all of that looking is used to dig into just what makes images tick.

Artworks are devices for engineering attention. What an artist chooses to do with that attention is the all-important question. Celmins hands it back to us as a gift.

This Issue

December 5, 2019

Against Economics

Megalo-MoMA