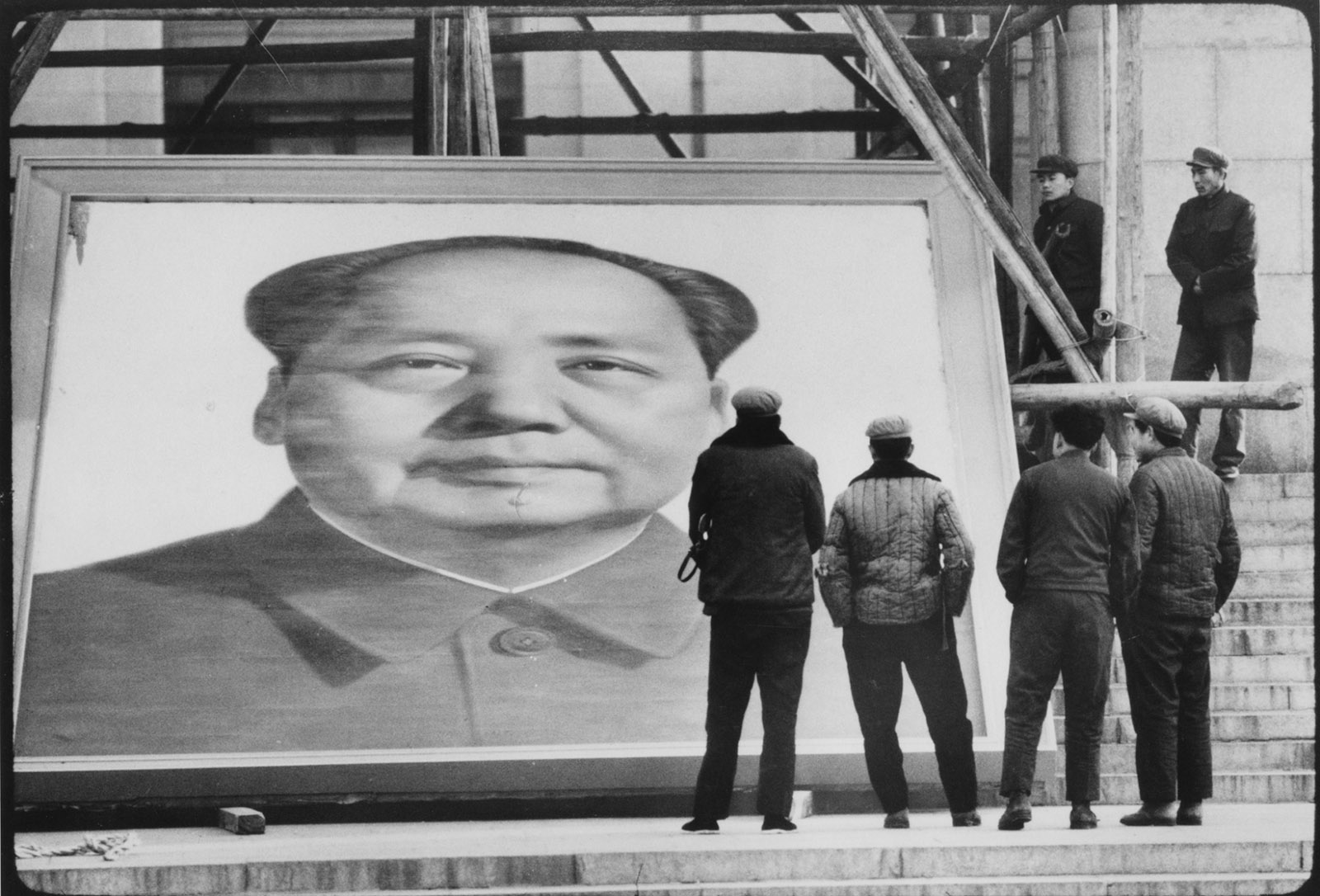

On a blistering Saturday last summer, I made my way to Shanghai’s western waterfront, where an extravagant new cultural corridor has been rising in recent years. My first stop was the cavernous Long Museum West Bund, which was opened in 2014 by Liu Yiqian, one of China’s most ambitious billionaire art collectors. Featured on the ground floor of the hulking concrete structure was a lively exhibition of mixed-media work by the African-American artist Mark Bradford, titled “Los Angeles.” But my attention was drawn to another show, in the museum’s underground galleries, whose poster featured an unfamiliar, smiling image of the young Mao Zedong and bore an intriguingly vague, almost meaningless title: “Thinking of the Seven Decades History at My Space.”

What I discovered, nearly hidden away, was room after room of outsized paintings of the Chinese revolutionary leader, most of them dating from the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s. Here was Mao at a desk, tracing his finger across a large map of the Taiwan Strait, as if planning an invasion. There was Mao in a heavy winter coat, writing calligraphy by lantern light. Two tableaux showed him beaming as he walked with overjoyed peasants through their fields. Others showed Mao on horseback or on the deck of a ship, heroically leading troops in battle. The legend inscribed at the bottom of yet another of these images read, “Chairman Mao Zedong is the Red Sun in the Heart of the World People’s Revolution.”

Many people have seen Mao kitsch of various kinds, but even for a longtime and frequent visitor to China, being confronted with such a concentration of it felt unusual. How to explain the effusive glorification of Mao during his lifetime, and why was such an extraordinary collection now stashed away in a cellar? The show’s English-language catalog essay was not of much help. In a passage under the heading “Admiration and Praise,” it said:

The works created by Mao Zedong’s portraits, statues, and Mao Zedong’s themes have developed greatly in the 1960s, not only in the large increase in the number and the expansion of the scope of expression, but also in the way of expression. It shows the creative characteristics of the ten years after the mid-1960s.

For anyone familiar with Chinese history, presumably including Chinese visitors to the show (who that day were few and far between), this can only be described as a grand evasion. The ten years in question were those of the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), a traumatic time of widespread political violence and upheaval, as the aging Mao stoked youthful radicalism in a bid to extend his already long hold on power.

Two new books cast fresh light on these questions and on China in that era. China’s New Red Guards: The Return of Radicalism and the Rebirth of Mao Zedong by Jude Blanchette, a scholar of Chinese politics at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, focuses on the surprising influence that Maoism still has in today’s China, which has been rebuilt on a model of Leninist state capitalism that bears little resemblance to the radical egalitarianism and virtual autarky that prevailed under the founder of the People’s Republic. Early on, Blanchette bluntly addresses the question of why the Chinese state went to such extraordinary lengths to celebrate Mao while he was alive. “Without the cult of personality for Mao Zedong, our Communist Party might have remained a sheet of loose sand and would have remained groping in the darkness,” a present-day proponent of Maoism tells him.

Maoism: A Global History by the British historian Julia Lovell provides, by contrast, a richly detailed and wide-ranging account of the emergence of Maoism and its evolution as a political force, first within China and then, to a remarkable extent, overseas. Her book proceeds from the claim that despite its impact on nearly every continent, Maoism remains woefully underexamined. “Maoism not only unlocks the contemporary history of China,” she writes in the introduction, “but is also a key influence on global insurgency, insubordination and intolerance across the last eighty years.”

There has been a much-belated recognition that Mao, who assumed the leadership of China in 1949 and ruled until his death in 1976, was one of the bloodiest leaders of the twentieth century, very much in a league with Hitler and Stalin. This reappraisal has come largely on the strength of two recent histories of the Great Leap Forward, Mao’s catastrophic program of accelerated collectivization and industrialization between 1958 and 1962: Tombstone: The Great Chinese Famine, 1958–1962 (2012) by the Chinese journalist Yang Jisheng, and Mao’s Great Famine: The History of China’s Most Devastating Catastrophe, 1958–1962 (2010) by the Dutch historian Frank Dikötter.* The best current estimates of the number of people killed by politically induced famine and terror during this period alone hover in the range of 30 to 40 million. As high as these estimates are, they do not include large numbers of Chinese who were killed during a violent land reform movement in the 1950s and the so-called Anti-Rightist Campaign later in that decade, or the million or so killed during the Cultural Revolution’s years of political violence.

Advertisement

Paradoxically, as Lovell makes clear, despite such rampant killing, as well as China’s generally woeful economic performance under Mao, this was also the era of the greatest soft power—its ability to influence others through its political ideals or culture—that the country has enjoyed in modern times. What, then, was Maoism? Despite Lovell’s thorough treatment of the Mao period, the answer proves somewhat elusive. This is the result not of a defect in her analysis but of the difficulty of defining the ideology of a charismatic, totalitarian leader driven by frequently shifting whims. In her best attempt at an answer, Lovell writes:

The term “Maoism” became popular in the 1950s to denote Anglo-American summaries of the system of political thought and practice instituted across the new People’s Republic of China. Since then, it has had a fractious history. Its Chinese translation, Mao zhuyi, has never been endorsed by CCP [Chinese Communist Party] ideologues. It is a dismissive term used by liberals to describe adulation for Mao among contemporary China’s alt-left [the topic of Blanchette’s book], or by government analysts to describe and disavow “Maoist” politics in India or Nepal today.

Historically, she adds, the ideology’s essential core was “veneration of the peasantry as a revolutionary force and [Mao’s] lifelong tenderness for anarchic rebellion against authority,” which was joined with a “veneration of political violence, [a] championing of anti-colonial resistance, and [the] use of thought-control techniques to forge a disciplined, increasingly repressive party and society.” She might have added the abolition of most private property and private markets as well as continual “class warfare,” or struggle against privilege, real or exaggerated.

At home, Mao’s personality cult was so total that, according to one estimate, by 1969 nearly 90 percent of China’s population routinely wore a Chairman Mao badge. Around that time, both his politics and his style of rule were being widely emulated in the third world, a term that Mao himself popularized as a way of differentiating China from the United States and the Soviet Union, which as superpowers he placed in the first world. The putative second world consisted mainly of Japan, Canada, and Europe. Mao placed China in the populous and relatively poor third world, which he aspired to lead. Mao’s China was a resource for would-be revolutionaries, anti-imperialist politicians, and liberation movements across the globe during the era of decolonization from the 1950s to the 1970s. It provided a powerful example of what a disciplined and ruthless Leninist-style political movement could accomplish through secretive organization, ideological indoctrination, mass spectacle, and political violence, which often took the form of asymmetrical or guerrilla tactics, known as People’s War. To illustrate Maoism’s influence, Lovell’s narrative moves chapter by chapter from a Communist insurgency in Indonesia to the Shining Path in Peru and from a contemporary and long-running Naxalite rebellion in India to Cambodia’s Khmer Rouge.

Under Mao, as Lovell repeatedly documents, China stood ready to provide arms, training, and cash to movements in Asia, Africa, and Latin America that solicited its patronage. Indonesia provides one example. Its Communist party, the PKI, embraced Maoist rhetoric and grassroots organizing, with its leader, Dipa Nusantara Aidit, taking instruction from Mao’s longtime prime minister, Zhou Enlai, during a special training course in China in 1963. Mao also had great sway with the country’s authoritarian president, Sukarno, and two years later promised him 100,000 small arms for free, ostensibly to help Sukarno counterbalance the country’s powerful army. Indonesia’s Communists became the target of a crackdown in October 1965 by General Suharto, who would later seize power and consolidate it with a genocidal purge of alleged PKI members and their sympathizers throughout the country.

Maoism’s other influential innovation was highly personalized dictatorship under an unquestionable leader whom the masses were forced to follow and revere. In this, it was influential well beyond aspiring third-world Marxist dictators or liberation movements. In the 1960s the longtime ruler of Zaire, Mobutu Sese Seko—no man of the left—fancied himself, like Mao, the national “helmsman” and “guide” whose words must be memorized by all and ritually danced and chanted; he even banned Western-style suits, replacing them with an African version of the Mao suit.

Lovell presents Cambodia as the most extreme example of imitation along these lines. In June 1975—two months after the Khmer Rouge took power, abolished the national currency, and ordered the evacuation of the country’s cities (Lovell writes that “an estimated 20,000 people died of snap executions, hunger and disease in the emptying of Phnom Penh alone”)—Mao received Cambodia’s new leader, Pol Pot, in Beijing and told him, “What we wanted to do but did not manage, you are achieving.” This was likely a reference to what Mao regarded as his stalled or incomplete Cultural Revolution. Understanding the power of flattery, Pol Pot told the Chinese leader, whose health was fading fast, “In future, we will be sure to act according to your words…. The works of Chairman Mao have led our entire party.” Under the Khmer Rouge’s four-year rule, as many as two million people—a quarter of the population—perished. That year, Mao gave Cambodia perhaps the largest amount of aid in China’s history: $20 million as a gift and $980 million as an interest-free loan. A few years earlier, Lovell also reports, “China [had] postponed the building of its own metro in Beijing to build one for Pyongyang instead.”

Advertisement

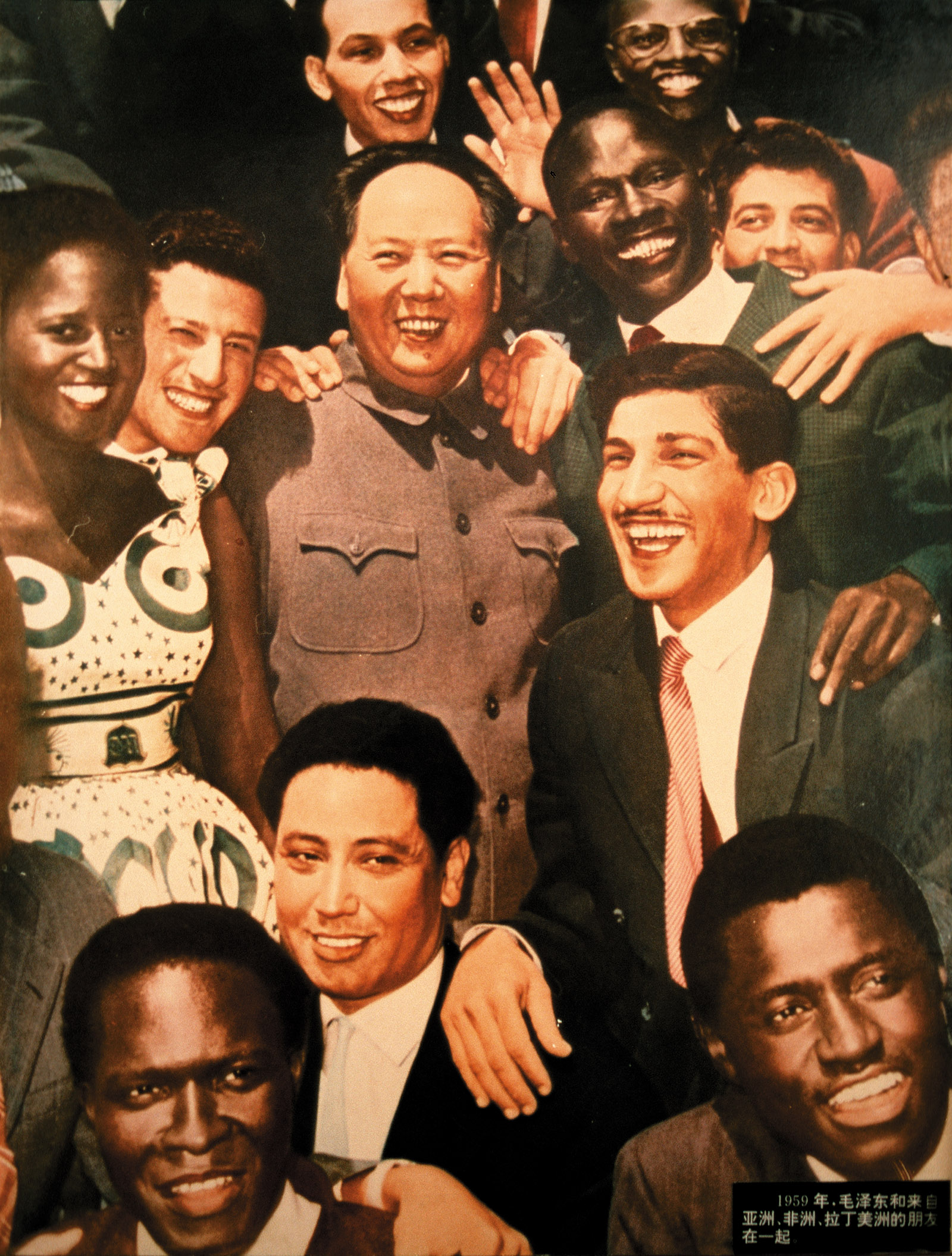

Why did such gigantic sacrifices seem worth making at a time when China was roughly as poor per capita as Bangladesh? Part of the answer lies, of course, in Mao’s extravagant ego, but there was more to it than that. Lovell depicts a modernizing Communist state that has retained many reflexes from its long imperial past, especially what she calls a “Middle Kingdom mentality” of wanting “to occupy the centre of the world.” The eminent Harvard historian of China John King Fairbank wrote decades ago that having ritual displays of foreign adulation and tribute had always been seen as central to the legitimacy of China’s leaders and ultimately to its stability. This reminded me of a painting in the Shanghai exhibition, one of the few tableaux that did not feature Mao. It portrays instead Zhou surrounded by black peasants on a visit to an unidentified African country. Zhou bathes in their jubilation but is the only individual given a face. “The idea of an approving foreign gaze—that events in China were inspiring revolutionaries all over the world—was intensely important to those propelling the revolution,” Lovell writes.

China’s present leader, Xi Jinping, heads an incomparably richer country, which spends tens of billions in a methodical drive to win friends and boost China’s position in the world. Measured against the widespread impact of Maoism, though, Xi’s efforts have fallen far short. “Within Europe,” Lovell writes in one description of the formidable range of influences that Xi’s forbear came to enjoy,

Mao’s Cultural Revolution galvanised Dadaist student protest, nurtured feminist and gay rights activism, and legitimised urban guerrilla terrorism. In the United States, it bolstered a broad programme of anti-racist civil rights campaigns, as well as sectarian Marxist-Leninist party-building.

Even this, however, only begins to describe Maoism’s reach. During Mao’s lifetime, the Chinese government oversaw the distribution domestically and overseas of roughly a billion copies of Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-Tung—the compilation of his revolutionary aphorisms, also known as the Little Red Book. His defense minister, Lin Biao, called it a “spiritual atom bomb of infinite power.”

Anyone under fifty might be surprised to learn just how deeply Maoism affected Western popular culture. After a visit to China in 1972, for example, the American actress Shirley MacLaine wrote a paean to the country—then in the throes of the Cultural Revolution—in her book You Can Get There From Here:

I was seeing that it was possible somehow to reform human beings and here they were being educated toward a loving communal spirit through a kind of totalitarian benevolence…. Maybe the individual was simply not as important as the group.

The year before, the Italian director of spaghetti westerns Sergio Leone opened his film A Fistful of Dynamite by quoting one of Mao’s sayings: “A revolution is not a dinner party, or writing an essay, or painting a picture, or doing embroidery.”

In Europe, Maoism was embraced by radical groups like the Red Army Faction, and in the United States by the Weather Underground, out of the belief that both capitalism and established authority were inherently illegitimate and corrupt and that violent rebellion was justified. The Black Panther Party meanwhile quickly became known in the US for its most famous slogan, the Maoist-sounding “Power to the People,” usually shouted with a hoisted fist. Bobby Seale, a leader of the Panthers, said the group’s inner circle

used the Red Books and spread them throughout the organization…. Where the book said, “Chinese people of the Communist Party,” Huey [Newton] would say, “Change that to the Black Panther Party. Change the Chinese people to black people.

When asked why he kept a poster of Mao on his apartment wall, Eldridge Cleaver, another Black Panther leader, was more blunt: “Because Mao Zedong is the baddest motherfucker on planet earth.”

I can attest to the resonance of Mao Zedong’s ideas for a generation of Americans who were coming of age at that time. My parents were active in the civil rights movement of the early 1960s. They knew its top leadership and provided medical support during some of the great marches in the South. An older sister of mine, however, made a break with the civil disobedience strategy epitomized by Martin Luther King Jr. and his peers, joining the Black Panthers instead.

A few years later, as a high school student, I read and was powerfully affected by many of Mao’s writings, including both his poetry and his political works. When he died I was in college but spending time in Africa, where my family had moved. Still under the sway of Mao’s ideas, I initially lamented the initiation of capitalist-style reforms under Deng Xiaoping, who succeeded Mao after a brief transitional period under Hua Guofeng. It was clear that this was, by design, the definitive end of class struggle in China and of the war against entrenched elites, or “continuous revolution,” that Mao had preached.

What made Mao’s ideas so attractive not just in the so-called developing world but also to a bookish, middle-class, African-American youth who sported a large Afro, in keeping with the spirit of the times? As Lovell explains, part of the answer lies in the surprising truth that some of his best-known ideas share a passing kinship with the philosophy of some of America’s founders. A Mao slogan I particularly admired was “To rebel is justified.” To an impressionable young man, one could hear echoes in this of Thomas Jefferson, who wrote, “I hold it that a little rebellion now and then is a good thing, and as necessary in the political world as storms in the physical.” Mao and Maoism, Lovell writes, “agitated to give voice to the marginalised, and to prevent the inevitable flow of power to technocratic metropolitan elites.” There was also a resolute hostility to inequality in his writings and a recurrent insistence that through organization, will, audacity, and zeal, the poor and weak of the world could overcome their oppressors.

Finally, as Lovell astutely observes, China under Mao was able to leverage racial identity during the cold war, whose two main opponents, the United States and the Soviet Union, were both perceived as dominated by whites. “You are still white,” she quotes Africans telling the Soviets. “But [the Chinese] are yellow, closer to us.” Mao understood this and played it to the maximum, whether by celebrating Paul Robeson and hosting W.E.B. Du Bois or telling a banquet hall full of guerrilla trainees from Africa, “You’re more or less like us.”

In Lovell’s account, which is as much a portrait of Mao as of the shapeshifting phenomenon of Maoism, the Chinese leader emerges as someone who saw conflict as a path to truth, and as the ultimate rebel and “outlier.” “Bombard the headquarters,” he urged the revolutionary youth known as the Red Guards during the Cultural Revolution, even though he was himself the unquestioned leader of the country. “Don’t be afraid of making trouble. The bigger the trouble we make, the better…. There is great chaos under heaven; the situation is excellent.”

The roots of both Mao’s power and his appeal appear to have been twofold. From the very beginning of his ascent, he revered violence and prized control of it above all else, initiating a major bloodletting campaign against his own party in the early 1930s, just years before Stalin’s great purges began. “Only with guns can the whole world be transformed,” he wrote around that time. When he was cracking down on small rural landowners, Mao said, “The only effective way of suppressing the reactionaries is to execute at least one or two in each county…it is necessary to bring about a brief reign of terror in every rural area…[and to] exceed the proper limits.”

His other great weapon was his remarkable command of language, which Lovell describes as an “ability to create compelling, comprehensible narratives of human history, both ancient and modern.” Maoism’s political messaging worked through simple, confident explanations, and through its exploitation of socioeconomic crises. Imperialism, Mao said in a famous phrase, was a “paper tiger.” This rejection of conventional measurements of national strength convinced many of his Chinese and international followers alike that revolutionary zeal and sheer will could overcome nearly any obstacle. His way with words caused Edgar Snow, the American journalist and author of Red Star Over China (1937)—the adoring book that Lovell credits with launching Mao’s early reputation, both within China, where it was distributed in translation, and globally, where its readership ranged from Malayan rebels to Nelson Mandela—to describe the Chinese leader as “a rebel who can write verse as well as lead a crusade.”

In the years following Mao’s death, the Chinese Communist Party underwent a major crisis of reinvention. First came the arrest of a radical faction of Maoists known as the Gang of Four, which included his fourth wife, Jiang Qing, a leading figure in the Cultural Revolution. An early problem was what to do with the immense stockpiles of the printed writings of the departed leader, from mountains of Little Red Books to his collected works. Blanchette recounts the decision to shred most of them and to discard most of Mao’s ideas while preserving an exalted place for his image in Chinese life. Thus today his portrait sits atop the gate at Tiananmen Square and on almost every denomination of China’s paper currency. In fact, Blanchette argues, the CCP had little choice. The Soviet Union was able to de-Stalinize in part because it could still lean on the prestige of Lenin. After decades of suffocating one-man rule, China only had Mao.

Contemporary China treats much of its history under Mao as an embarrassment; it demands extreme selectivity and idealization in the official versions of his life, and imposes stringent censorship on scholarly and unofficial publications about it. There has never been a candid accounting to the general public, for example, of the Great Leap Forward, the Cultural Revolution, or the fomenting of revolt in countries near and far. This may help explain why China curates gigantic shows of Mao imagery yet hides them away in basements. Blanchette quotes Feng Chen, a Chinese political scientist:

As long as “socialism” remains symbolically important for the Party’s political legitimacy, the CCP has to bear the burden of justifying its current practices in socialist terms, which will therefore involve a protracted ideological battle with the leftists over what is authentic socialism and who represents it.

Much of this struggle plays out over the use of Mao’s name and image. China’s New Red Guards is the story of these battles. Blanchette minutely documents the rise of groups on the Chinese Internet that have used Mao to criticize the increasingly capitalist policies of the party, which have produced cronyism and corruption on a vast scale, along with stark inequality. Invoking Mao is like wrapping oneself in the flag; it provides a degree of protection from persecution, although there are limits. A network of pan-leftist websites like Utopia and Maoflag adopted this approach and grew increasingly dense and diversified, despite facing periodic crackdowns and blackouts. Blanchette speculates that the Maoist voices in venues like these benefit from protection from center-left forces that survive in the Chinese Communist Party and regard Maoists as a useful “radical flank” to help slow down the evolution away from socialist ideals.

Utopia has had a particular importance in this development. It began in Beijing in 2003, both as a website that welcomed left-wing opinion in China and a salon-like speaking venue for leftist scholars, intellectuals, and authors, with the humble intention of becoming “a small platform through which social progress can be facilitated by pursuing a fairness-first society and the formation and expansion of a responsible middle-class.” Success came quickly, though, measured by its Internet popularity and turnout at its events.

In Blanchette’s telling, beginning with Deng and continuing through the rule of Deng’s chosen successor, Jiang Zemin, China continued to move strongly to the right. First it opened up to private investment and globalization under Deng, and then it welcomed capitalists into the Communist Party under Jiang, who also took the country into the World Trade Organization. This made the pan-leftists furious, and they fulminated online against trends that they warned would drain Chinese socialism of all meaning. The most important of these trends were reforms aimed at privatizing state-owned industries. China was falling victim to something leftists (ironically) called “peaceful evolution,” which variously meant a plot by the party’s leaders to abandon Chinese socialism or a campaign by Western forces to constantly nudge China in that direction. One leftist figure, a party veteran named Ma Bin, argued in 2006 that every seven or eight years China should wage a new cultural revolution in order to prevent a “capitalist restoration.”

Under Jiang’s successor, Hu Jintao, seemingly in response to this pressure from the left, the Chinese state proclaimed a war against inequality, notably increasing social benefits for peasants. By 2006, however, the pan-leftist coalition was fragmenting, with some of the most successful Internet voices, like Utopia, turning aggressively nationalistic and openly Maoist in rhetoric. “From this point on, Utopia and an increasing cohort of competitors and copycats would embrace a paranoid worldview,” Blanchette writes, “that saw global conspiracies of Western domination, the infiltration of China and the party by traitors and ‘hostile forces,’ and a belief in an inevitable and unavoidable conflict with the United States.” Led by Utopia, the neo-Maoists also became more overt in their criticisms of establishment politics under China’s Communist Party. In 2012 Hu’s outgoing premier, Wen Jiabao, gave a news conference in which he warned ominously that the country could experience the convulsion of a second cultural revolution. The exact meaning of this comment was left open to interpretation, suggesting to some the need for greater reform in China aimed at reducing class disparities and official corruption, but to others the menace of an increasingly aggressive left.

The most prominent figure of this resurgent left was Bo Xilai, the charismatic son of a revolutionary comrade of Mao’s and the party secretary of Chongqing. During the transition between Hu and Xi, Bo attempted to upend the carefully choreographed succession and leapfrog his way into the senior leadership by organizing high-profile events, including a sweeping anti-crime crusade, adopting Maoist rhetoric against inequality and corruption, and assiduously courting the media, especially Utopia. By the eve of the 18th Communist Party Congress in 2012, many observers speculated that his efforts would be rewarded with a seat on the Politburo Standing Committee. What ensued instead was a downfall even more abrupt than his rise, after Bo’s police chief in Chongqing, Wang Lijun, unsuccessfully sought asylum in an American consulate and then denounced Bo as “the greatest gangster in China.” Soon afterward, Bo was stripped of his party posts and arrested, along with his wife, Gu Kailai, who was found guilty of the murder of a British business partner. Bo was tried for corruption, and both he and his wife are currently serving life sentences.

Blanchette observes that when Xi took office in 2013, most foreign analysts expected him to become a liberal reformer, reducing state control of the economy and perhaps allowing for more freedom of expression and association. He was thought to adhere to something called the Guangdong Model, so called because the Communist Party secretary of that prosperous province, Wang Yang, had been a conspicuous liberalizer. But once Bo was arrested, Xi did the opposite, more or less adopting his impatient rival’s so-called Chongqing Model, which called for injecting ever more money into China’s vast state-owned corporate sector to protect its underperforming companies from layoffs and failure.

Under Xi, not only has the state become much more deeply involved in the economy, but power has been more strongly concentrated in Xi’s hands than in those of any other post-Mao leader. A personality cult has grown up around him that is reminiscent of Mao’s, and the space for dissent has shrunk dramatically. Xi, who is sometimes called the chairman of everything because he personally oversees virtually all of the most important policy, planning, and oversight groups of the Communist Party—with the exception of the ongoing fight against the coronavirus epidemic, whose leadership he ceded to his ordinarily low-profile premier, Li Keqiang—has removed limits on his time in office that were instituted by Deng to prevent the rise of another leader like Mao. The lesson that Xi seems to have drawn from Bo’s rapid if brief ascent is that Maoism—built on the style and rhetoric of a paternalistic and all-powerful leader, whose personality cult keeps his benign visage in view at all times, with slogans that all citizens should be able to recite—remains such a potent tactic and resource that he cannot afford to dispense with it.

This Issue

March 12, 2020

Foolish Questions

A Very Hot Year

Serfs of Academe

-

*

See the review of both books in these pages by Ian Johnson, November 22, 2012. ↩