Since the comic book Love and Rockets debuted in 1981, Jaime Hernandez has created hundreds of stories about a Chicanx, queer, punk, middle-class Southern California world revolving around Maggie Chascarillo and her off-and-on lover, Hopey Glass. They are, Hernandez has said, his Mexican-American Betty and Veronica, inspired by the Archie Comics he read in his youth, and by the young women he observed in the late 1970s and early 1980s at punk shows in Los Angeles and his nearby hometown of Oxnard. Their sexuality, like that of the other characters in Love and Rockets, is fluid and, like their ethnicity, rarely the subject of any story. Hernandez has portrayed these people and places in crisp black linework verging on a warm cartoon minimalism—a versatile visual language that clearly establishes time, place, and mood without an omniscient off-panel narrator. Hernandez is always showing, never telling.

Maggie is a car-mechanic prodigy, who is romantic but ultimately practical. Hopey, eventually an elementary school teacher, is impulsive, prone to outbursts, and unafraid to hurt her loved ones, confident in her ability to lure them back. Maggie and Hopey have gradually aged perhaps twenty-five years since their introduction nearly forty years ago—they were punks, “it” girls of their scene, and then continued growing into complicated adults, allowing Hernandez and his earliest readers to explore their own lives through and alongside the characters, as with, say, François Truffaut’s Antoine Doinel or Philip Roth’s Nathan Zuckerman. Reading the earlier stories is not required to enjoy the current books, but it deepens the experience.

For the first decade and a half of Love and Rockets, Hernandez brought Maggie, Hopey, and their friends (including the super-heroic aspiring heiress Penny Century, the ageless witch Izzy Reubens, assorted band members, and paramours) through a range of escapades sprung from Hernandez’s obsessions. They explored an eccentric, devil-horned millionaire’s endless mansion; became embroiled in an epic and tragic gang dispute; found notoriety and failure in rock and roll, showbiz, and lucha libre; traveled North America; got stranded in Texas; and finally, by the end of the 1990s, settled back into Southern California and began to make lives for themselves rooted in middle-class adulthood. Hopey trained to be a teacher; Maggie managed an apartment complex. Their lives became disentangled from each other. Gradually, Maggie found her way back to a past boyfriend, Ray Dominguez, while Hopey married her longtime girlfriend, Sadaf, with whom she has a son. The charm of these characters is their fierce individuality, willfulness, humor, and candor across four decades of adventures both wild and mundane. How they’ve changed, together and apart, is the present business of Hernandez’s comics.

The first issue of Love and Rockets was originally self-published as an eight-hundred-copy black-and-white magazine by Jaime Hernandez and two of his older brothers, Mario and Gilbert. Mario, whose involvement was brief, produced fantasy stories. Gilbert’s contribution was the start of a still ongoing saga about a family of women from a Central American village called Palomar.1 The Hernandez brothers’ recurring characters have aged and sprawled out into baroque, visionary stories that alternate between near-anthropologic detail, fantastical pulp, and sexual fetishes. In 1982 Fantagraphics released an expanded version of that first issue in a print run of a few thousand copies and has published the series ever since, just over a hundred issues to date, with print runs peaking at 20,000 copies per issue in the late 1980s. The series has changed formats from magazine to comic to paperback digest and assumed a few different titles over the years—among them Penny Century and Luba’s Comics and Stories—but has always serialized Jaime’s and Gilbert’s stories. When Jaime finishes a Love and Rockets narrative arc, like Is This How You See Me?, he gathers it into a hardcover book resembling an Archie Giant Annual from the 1960s, containing stories that range in length from one to four to twelve to twenty-four pages, with multiple title pages, interludes, and the occasional non sequitur. Each of these hardcovers is in turn compiled into 250-page softcover compendiums in the Love and Rockets Library book series, fifteen volumes and counting.

Jaime Hernandez’s unique narrative structure and blend of genres is rooted in his upbringing in Southern California. He was born in 1959 and grew up in Oxnard, a mixed-race suburb sixty miles northwest of Los Angeles. His mother, Aurora, grew up in El Paso, Texas, and his father, Santos, in Chihuahua, Mexico; both worked in the fields and packinghouses near Oxnard that employed much of the working class. They met and married in the 1940s and had six children; Jaime was the fourth. His neighborhood, which he referred to as a little barrio, was small and compact—school was within walking distance and his uncle’s barbershop was nearby. Santos Hernandez died in 1968, when Jaime was eight years old, leaving Aurora to raise the family. She had grown up reading comic books including Superman and Doll Man and encouraged her kids to consume them as well. She entertained them with her own drawings of her favorite heroes and they, in turn, made and collected comic books.

Advertisement

Hernandez remembers loving the form even before he could read—Richie Rich, Dennis the Menace, Herbie, and Spider-Man were favorites. Chief among them were the tales of everyday life and hijinks with Archie and his pals, drawn from the late 1950s through the early 1970s by the clean-line master of body language Harry Lucey. Archie and his hometown of Riverdale are both confined and infinitely malleable. There is a set number of characters and locations but limitless potential for plots. Stories consist of simple scenarios—for example, the gang goes skiing, and Archie’s clumsiness on the slopes wreaks havoc on all humans and objects around him; Archie gets a new dog, and Veronica’s father teaches it to bark when Archie and Veronica smooch. Hernandez took a similar approach but with less innocent intentions, in order to tell us about the physical and emotional lives of his characters. He turned the implicit economic and racial politics of Archie on its head by substituting working class for upper class, people of color for white people, and city for suburbs. Perhaps because of its subtle and gradual execution, this transformation is rarely remarked upon, but there is little in comics history more subversive than that quiet act.

While the long-since-internalized plot mechanics and personal relationships of Archie power his stories, Jaime’s approach to chronology and character development is born of a particularly twentieth-century obsession with comics. That condition, which I and countless others share with the Hernandez brothers (albeit separated by time, geography, class, and ethnicity), resulted in a compulsion to seek out and collect past issues of our best-loved titles in order to understand the history of both the medium and the characters. Comics fans savored information about treasured characters, powers, places, and chronologies, information that was revealed over time but rarely in any kind of linear progression. A Marvel character would be introduced but his biography revealed only in random bits and pieces over a ten-year publishing span. This was not by design but rather a function of the comings and goings of writers, artists, editors, and publishers in a rickety third-tier publishing business.

Hernandez similarly works without a planned scaffolding, but by intention. There is not a grand map of plot and place, no guidebook. He works from instinct and can add to his cast as he needs to, secure in their emotional and psychological parameters. Hernandez made this ad hoc mode of world-building into a principle, moving his characters forward in time while constantly adding to their pasts in any sequence he chooses. He narrated Maggie’s childhood, for example, as part of a larger story in 2014’s The Love Bunglers. In that sense, he tickles the same part of my brain as those old 1960s Spider-Man comics.

That tickle, in concert with the Hernandez brothers’ open, generous approach to storytelling, helped win a diverse audience in mainstream comics and what was once called alternative culture—a network of music, publications, and films less interested in unified aesthetics or canons and more in finding a thing to listen to, a thing to read, something to look at that was unpretentious, independent, and personal. The latest Replacements record and the new Love and Rockets comic went well together, and both might be recommended by a friend, or reviewed in the same zine. Within the comics avant-garde itself, the response was a bit chillier. In the early 1980s American comics for adults were divided between two tendencies embodied in a pair of decade-defining anthologies: Weirdo and Raw. Founded by Robert Crumb (himself a Love and Rockets supporter), Weirdo anthologized artists on the margins of society and underground cartoonists—the more gut-wrenchingly personal or scathingly satirical the better. Raw, edited and published by Françoise Mouly and Art Spiegelman, was interested in advancing the medium through postmodern stories and irony-laden imagery.

Though far apart in their visions of what comics could be, both sides met in their disdain for mass-market 1960s comic books like Archie and Spider-Man, preferring instead their own canons of nakedly personal or formally sophisticated work by the likes of Fletcher Hanks, George Herriman, and Walt Kelly. There wasn’t much of a place in either camp for unironic, plot-driven stories about men and women coming of age, let alone Latinx and gay men and women. Through desire and necessity, the brothers carved out a place for themselves. They were used to it, having grown up as outsiders—keenly aware that their cultural mix of Mexican food, folk stories, wrestling, and film mixed uneasily with their self-described American pop-culture addiction.

Advertisement

Hernandez’s embrace of these otherwise critically scorned languages and genres is also related to his teenage discovery of punk rock. The Los Angeles punk scene had a strong Latinx presence, including Alice Bag of the Bags, the Plugz, and the Zeros. Oxnard in the early 1980s had its own hard-core scene, which the brothers frequented in addition to trips to the LA shows; Jaime’s brother Ismael played bass in a local band, Dr. Know, and Gilbert and Jaime had their own bands, Beer Guts and Suspicion. For Jaime, punk meant freedom. In a recent interview for a volume of his original drawings, Jaime Hernandez Studio Edition, he told the Fantagraphics cofounder Gary Groth:

Punk came along and freed me, like, “I don’t have to answer to anyone.”…It made you see the world bigger and how things were, it also gave you permission to be stupid. I could be silly. I didn’t care anymore what people thought if I was silly.2

In the last couple of decades Hernandez has, in turn, offered permission to a more diverse, emotive, and narrative-minded generation that has embraced the medium, including cartoonists such as Alison Bechdel, Frank Santoro, and Jillian Tamaki.

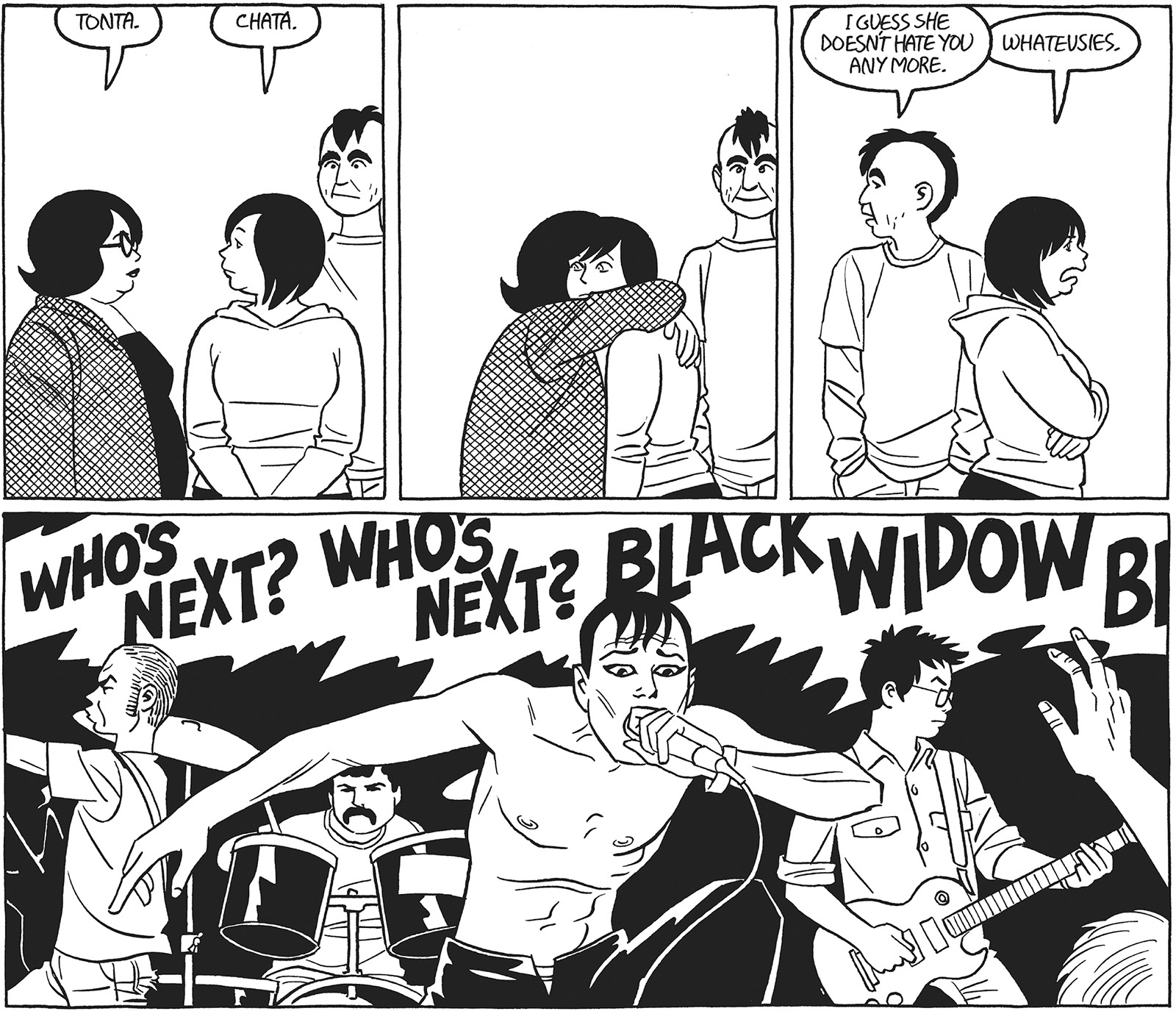

Jaime Hernandez’s two most recent hardcovers, Is This How You See Me? and Tonta, contrast the weight of youthful memories with youth lived in the now: the former continues the story of Maggie and Hopey as they return to their hometown of Hoppers for a punk reunion, whereas the latter anthologizes four years of stories about a new character in the Love and Rockets world (and from which Maggie and Hopey are conspicuously absent).

That character is Tonta (“stupid” in Spanish—her mother is Mexican-American), a high school student whose given name is Anoush (“sweet” in her father’s native Armenian). She is as guileless and awkward as Maggie and Hopey were confident and forthright at her age. We meet her on the first day of summer break on a hill in the San Fernando Valley. She is a kind of tumbling balloon of awkwardness that seems unlikely to ever right itself, knocking into subplots as she goes. She’s obsessed with her favorite punk band, Ooot—the lead singer has just been deported to Guatemala, but no matter, Tonta prefers the replacement. And she’s friends with a disfigured (and possibly supernatural) fellow student nicknamed Gorgon, who seems to inhabit the nearby woods. In Tonta, Hernandez, now sixty, can look at contemporary youth unburdened, for the most part, by decades of stories.

Tonta is connected to the larger Love and Rockets narrative through her older half-sister, a sexually fluid underworld gun moll and stripper named Vivian, who has hung around Hernandez’s stories for just over a decade—a relative newcomer. Vivian’s criminal connections and crossed affairs culminate in dangerous secrets revealed, a court case, and the sad paths of Tonta’s extended family, which consists of three other half-siblings, who, after years of separation and conflict, come together to accuse their mother of murdering her first husband and plotting to kill her current spouse, Tonta’s stepfather. Another connection is a younger friend of Maggie’s named Angel Rivera, who is the incoming PE teacher at Tonta’s school and a wrestler in a lucha libre league in nearby Tarzana. Mexican wrestling has been an enduring fascination for Hernandez—he devoted an exhilarating Love and Rockets spin-off comic book series, Whoah, Nelly!, to it—and Maggie herself was raised in part by her wrestling-champion aunt. Angel, though she seems glamorous and self-assured to Tonta, is trying to find her place as an adult. As Tonta’s family is in turmoil, we watch Angel wrestle, suffer a loss, and settle into her new job. The stories in Tonta gradually expand our vision of Tonta’s world from adolescent concerns to crime, family secrets, and tragedy. This deft blend of genres is typical of Hernandez’s work.

All of these characters, themes, and narrative strands would not cohere if Hernandez wasn’t one of the most fluid, precise, and graceful cartoonists in the history of the medium. His refined lines, made with a Hunt Extra Fine No. 22 pen, distill multiple strains of cartooning and commercial art into a handmade (no rulers allowed) language of structural and emotional perfection. Lines move from thick to thin, they are uneven—there is life in them. It’s rather like the way we think of an Alberto Giacometti drawing: he’s finding the form, finding the character, as he draws it. The best narrative cartooning (and Hernandez is arguably the finest narrative and character-based cartoonist working today) is based in shorthand drawings of place, space, emotions—things that would consume pages of prose or occupy an entire Félix Vallotton canvas. Other cartoonists do this, of course, but none have the elegance and beauty of Hernandez as an artist. At any level, this is rare in comics; some of the best-written comics have dull drawings, and some of the most intriguing drawing is in service to lousy stories. In Hernandez the writing and images are perfectly in harmony, undergirded by a consistent panel and page structure so traditional as to be nearly subliminal.

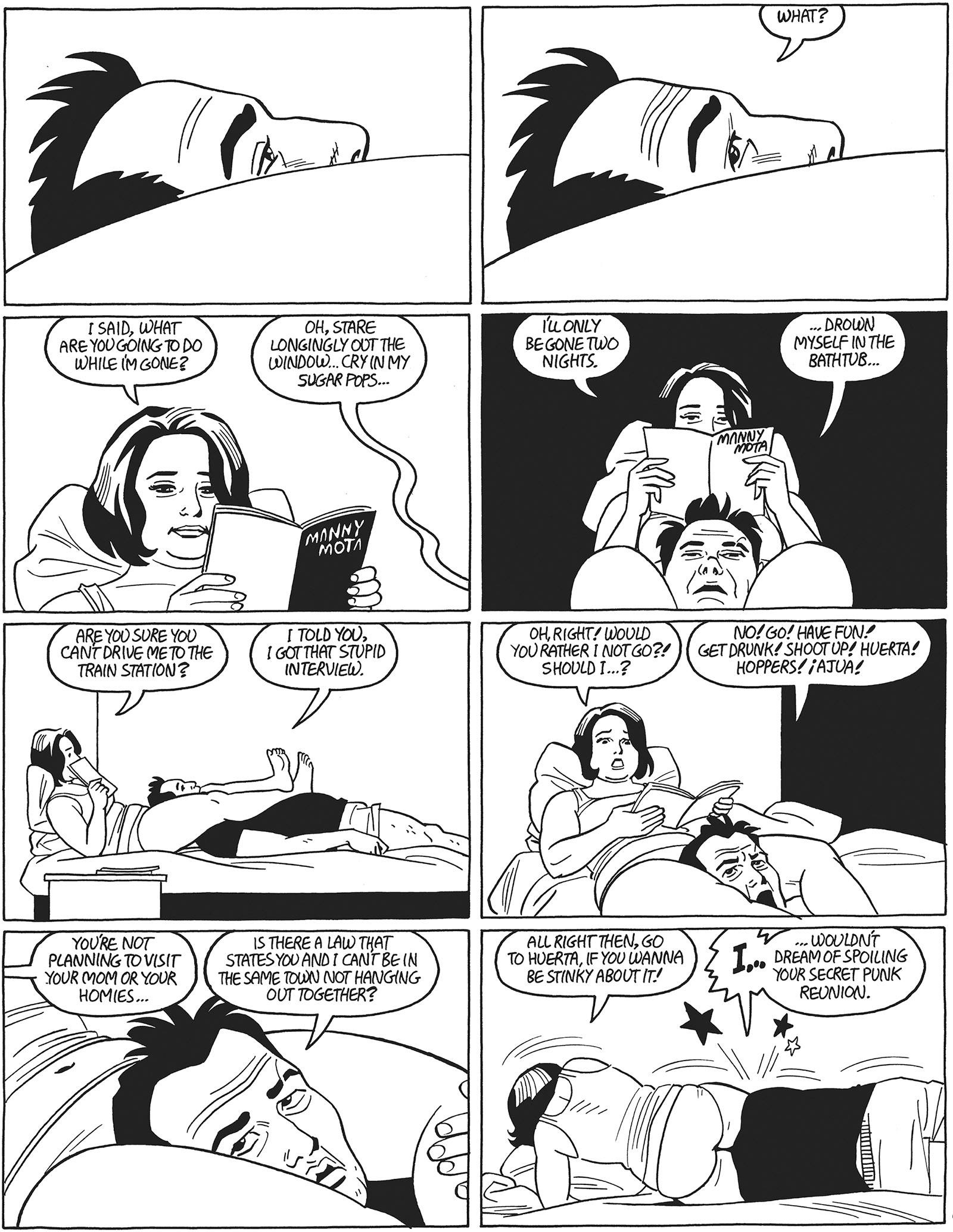

Is This How You See Me? begins with sixteen identically sized panels in which Maggie and her partner, Ray, lie in bed in their Van Nuys apartment and discuss Maggie’s upcoming two-night trip to Hoppers with Hopey, who is now married and raising a child with her wife, Sadaf, in the Mount Washington area of Los Angeles. The two-page sequence turns from talk to sex in the thirteenth frame, in which Hernandez’s precise linework quickly communicates the lived-in comfort of their relationship: Maggie on her stomach facing away from the viewer, Ray resting his head on her left thigh, his legs kicked up on the wall. Maggie leads the seduction and ends the prelude with a moan for both Ray and Hopey, which points toward the central preoccupation of the book: the effect of time and memory on relationships. This is the last time we see Maggie and Ray together in the present.

Hernandez tells stories more with body language, action, and evocative pen marks than with text. We learn more about Maggie’s ambivalence toward the weekend ahead from her posture in this sequence than from anything she says. Hernandez has mastered a beautiful cartooning style that shows us a story, allows our own conclusions, and moves along. We can slow down and admire the sheer beauty of the art or take it in at a gallop to move through the plot. He explained his method to Groth this way:

Everything I draw is trapped in the laws of gravity. And knowing that there’s a skeleton inside…. Even if Maggie is just standing there listening to someone talk, I know what’s going on inside her body. I know there’s earth under her feet. I know certain feelings she’s having are causing her body to do certain things…. There’s a bigger world around ’em, that when I’m drawing Maggie standing around talking, I know there are people miles away from her. I know there are cities. I know there are people who don’t care about what she’s going through. I know there’s traffic driving by, whether I show it or not. I know the sounds that are happening, because she’s outside on a busy street talking to somebody. I just know all this stuff is going on even if she’s just standing there with a dumb look on her face.

Encountering the people and places of their past during the reunion in Hoppers leads Maggie to disagreements, disappointments, and memories both warm (their first meeting) and troubled (a close call with a predatory owner of a punk house). She and Hopey, as they have for decades, fall out before they even get to their destination. Each is temporarily free of her daily circumstances but unable to enjoy her escape. They circle their old haunts, encounter old friends and foes, and attend the reunion show, at which their favorite band, Ape Sex, in no mood for forced nostalgia, doesn’t even perform. Two narratives interrupt the primary action: short monologues delivered by Ray on Maggie, movies, and memory; and a story set in 1979 and 1980, before the events depicted in the first Love and Rockets comic book—the young Maggie and Hopey first meeting, falling into each other, assured of their impulse for invention, of life and its dangers. The older Maggie and Hopey are forever competing with their younger selves, both in their own minds and as characters to readers who treasure those spunky punks. After the show they are joined by a group of friends familiar to longtime readers, eating at a diner discussing menopause and the flashbacks we’ve just read.

On their way back to the hotel from the diner, Maggie and Hopey are stopped and harassed by millennial urbanites in athletic gear: “You know you’re going to hell with all your gay trans bullshit.” It’s a final rebuke to their youth, identities, and the very place where they embraced both. Is This How You See Me? closes with a page-and-a-half coda showing Daphne, a friend of Maggie and Hopey’s from the early days, in a grocery store. She’d brought her Ape Sex T-shirt–wearing daughter to the punk reunion. One of the band’s songs floats over the sound system shortly after a Phil Collins tune. Daphne smiles, unbothered. She was always a tertiary character, never in a band or involved in a loony adventure. Maggie and Hopey were the center of every room, scenester legends remembered by Daphne’s kid and her friends. But their history is a burden. Daphne, living in the present, is free of old memories and youthful expectations.

The nearly forty years of Love and Rockets has facilitated a narrative sprawl unique in comics for its scope and depth. I remember first reading it in suburban Washington, D.C., in the early 1990s when I was younger than Hernandez’s characters, knowing Hoppers was fiction but that there were places and people like this, out there, and I wanted to know them. When I read contemporary Love and Rockets issues in the early 2000s, I recognized a life after alternative culture, one bound by nine-to-five jobs and financial constraints. Now middle-aged and reading the recent books, I empathize with Hernandez’s evident joy in Tonta and his more pensive ruminations on nostalgia, old loves, and memory itself. It’s an unsettling if also comforting intermingling of reader, cartoonist, and characters.

Is This How You See Me? is, finally, a book about living with the ghost of your younger self. It’s a book best understood with both the weight of Love and Rockets and one’s personal past. Tonta, however, is a book of rebirth, in which Hernandez introduces all his obsessions—wrestling, punk, ghost stories, crime, and love—into the story of a teenager just beginning to accumulate the kinds of memories that Maggie and Hopey (and we) already share. They have become. Tonta is just becoming.

-

1

Fantagraphics also publishes most of Gilbert Hernandez’s Palomar-rooted solo work. These stories have become more pulpy and urgent in recent years. His latest graphic novel, Maria M., purports to be a film version of a story he first serialized thirty years ago, though it also functions perfectly as a gangster story replete with ruthless violence and high drama. Other publishers have released Gilbert Hernandez’s stand-alone explorations in memoir, zombie horror, and science fiction. ↩

-

2

Gary Groth, “Interview,” in Jaime Hernandez Studio Edition (Fantagraphics, 2017). ↩