A third of the way through D.W. Griffith’s film The Birth of a Nation, the American Civil War ends. With the defeat of the Confederacy, the southern white population is now kept in subjugation by white northern “carpetbaggers” in league with newly appointed black legislators.

Early on in the film (based on Thomas Dixon’s novel The Clansman), a black face appears on the screen. Gus, one of the liberated enslaved, in the uniform of the Union Army, loiters outside the house of the virginal southern belle Flora and follows her to the woods. The “black brute,” with “his yellow teeth grinning through his thick lips,” as Dixon describes him, proposes marriage. Flora recoils in horror and scrambles into the woods with Gus in pursuit. Rather than submit to the rape that he surely intends, she edges onto a mountainous ridge and leaps to her death. Vengeance is required. By the film’s end the Ku Klux Klan, in theatrically grotesque hoods, their white robes flapping with terrifying certainty, track Gus down and lynch him.

Notwithstanding The Birth of a Nation’s cinematic innovations, it was the film’s emotional and racial incitements that fired up audiences when it was shown across the US in 1915. The vexed included President Woodrow Wilson, who, after a private screening in the White House, is alleged to have said, “It is like writing history with lightning, and my only regret is that it is all so terribly true.”

Two years later, when Wilson took America into World War I “to make the world safe for democracy,” black leaders such as Marcus Garvey argued that while the president’s global ambitions were admirable, perhaps he’d like to start closer to home and make America safe for democracy first. For in the years following the release of The Birth of a Nation, membership in the Ku Klux Klan soared and there were several hundred lynchings, for which the Klan had been known since its first appearance in the 1860s.

Among those implicated in the fledgling Klan’s earliest atrocities was a Louisiana carpenter and former Confederate soldier, Polycarp Constant Lecorgne, a great-great-grandfather of the writer Edward Ball. In Life of a Klansman, Ball presents the story of his ancestor as a case study in the enduring legacy of slavery. The book is part memoir (exploring family lore of how Lecorgne became a Klansman), part history (conjuring the antebellum South, the Civil War, and Reconstruction), and part discursive essay (with reflections, for example, on the invention of whiteness).

Ball recognizes that Lecorgne, a French-speaking Creole who lived most of his life (1832–1886) in New Orleans and fought to maintain the primacy of whites, was a “family hero of sorts…before standards changed, and his memory became too hot.” Nonetheless, he was still considered by some, like Ball’s aunt Maud, to have been a “Redeemer [who] helped to end Reconstruction,” and “for a long time, nobody said that was a bad thing. Except perhaps the Negroes.”

Ball’s earlier excavation of family history, the National Book Award–winning Slaves in the Family (1998), concentrated on his father’s side, “one of America’s oldest and largest slaveholding clans,” and in researching it he tracked down descendants of those his ancestors had enslaved. They included Leon Smalls, who doubted whether a white supremacist mentality had ever disappeared after the end of slavery:

“We today think that things have changed…. I work with a group of people who, the only difference is they leave their sheet at home. But they still have them in their closets.” [Smalls] was referring to the hoods and sheets of the Ku Klux Klan, though neither of us let those words pass our lips.

In Slaves in the Family, Ball largely eschewed writing about the family of his mother, Janet Rowley, who was born in New Orleans and, like her husband, had a plantation heritage. Ball recalled, “A yellowing photograph of the Seven Oaks mansion used to hang in the hall of our house…. By the time of the photograph, the plantation had long passed out of the family and stood abandoned and decrepit.”

This relatively poorer side of Ball’s family (which included Constant Lecorgne), whose fortunes faded after the Civil War, is explored in Life of a Klansman, a further confrontation with the toxically interconnected lives of blacks and whites. Lecorgne’s tale may have been a family secret, but Ball argues that, directly or indirectly, all Americans have skin in this game. By 1925, a decade after the release of The Birth of a Nation, the KKK could claim five million members, which suggests, according to Ball, that today one half of the white US population has a family link to it.

Life of a Klansman, tracing those connections, begins on March 4, 1873, a night of high drama, folly, and fervor. The forty-one-year-old Lecorgne, a father of six, emerged from his house by the levee of the Mississippi River three miles upstream from the old center of New Orleans, carrying a gun. Soon he joined thirty other members of his Ku-klux gang, mostly veterans of the Confederate Army, for an assault on the station house of the multiracial Metropolitan Police. As elsewhere in the book, Ball’s use of the historical present not only illuminates a Klansman’s thinking but lends an immediacy to the writing:

Advertisement

The men shoot up the doors and windows…. Constant is like the blade on a knife. He is in the door, a gun pointing at heads…. The police are not ready for them, the Metropolitans surrender. Two of the cops are Creoles of color…. They get extra attention, some roughing up, the butt of a gun on the head. But no one, yet, is shot.

The shooting started, but the white insurgents’ attempt to overthrow the representatives of the US government and secede from the Union failed. Half the gang fled. Lecorgne and the remaining accomplices were arrested and charged with treason, but they did not hang for it. Life of a Klansman then flashes back cinematically to the origins of the Le Corgnes (subsequently Lecorgnes) in Louisiana, with the desertion by Constant’s father, Yves, from the French navy and his arrival in New Orleans in 1814, before we learn how Constant escaped the hangman’s noose.

Yves Le Corgne’s marriage into the plantation-owning family at Seven Oaks set in motion their trajectory from poor petits blancs (little whites) to modestly wealthy grands blancs (big whites), with an investment in slavery and acceptance of its brutality. Ball conjures how Yves’s young wife, Marguerite, might have witnessed the summary justice that followed slave insurrections: “When she puts on her fresh linen, stands on the levee in front of her house, and looks across the river, what she sees are fence posts topped with black heads, their faces twisted in the agony of gruesome death.”

The Lecorgnes had no respect for their enslaved workers, only for their monetary value. When Constant’s mother was bequeathed eight “items” (enslaved people) on her father’s death, her family was suddenly elevated to the ranks of the grands blancs. She sold four of them and leased the others: “To possess four slaves in the city is like owning four houses to rent,” Ball writes.

Slaveholders deflected any sense of guilt for the inhuman treatment of those they enslaved by citing church sermons and scientific reports. The Old Testament reassuringly taught that “now therefore, you are cursed, and you shall never cease being slaves, both hewers of wood and drawers of water for the house of my God.” Ball explains that the scientist and collector of skulls Samuel Morton gave cover to this biblical view in Crania Americana: An Essay on the Varieties of the Human Species (1839), which put forward “the fable…known as ‘polygenesis.’” From his research into the length of jawbones and skull capacity, Morton determined that there were five races, including “Ethiopians,” a people he characterized as “joyous, flexible, and indolent,” and “Caucasians,” who “surpass all other races.”

Ball doesn’t suggest that Constant or any of his relatives were familiar with Morton’s essays. His purpose here is to paint in the background noise prevalent in the antebellum southern states that prompted The Charleston Medical Journal to conclude, “We of the South should consider [Morton] as our benefactor for aiding most materially in giving to the negro his true position as an inferior race.” Science and religion combined to convince Constant’s father of the rightness of his good fortune. In 1840, with the family’s inherited windfall, he traded “four nègres for six pieces of land in a new section of uptown [New Orleans] called Bouligny.”

The lives of enslaved people of color were unknown to slaveholding families; they were marginal and unconsidered, caught fleetingly from the corner of the eye. Only in personal accounts such as Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass were black lives fully illuminated. The Lecorgnes would have been familiar with Douglass (a name that caused some white people to “spit when they say it,” according to Ball), and at least aware of the great abolitionist’s 1852 speech in which he asserted that for the enslaved, the Fourth of July was a cause not for rejoicing but for mourning:

Your shouts of liberty and equality, hollow mockery; your prayers and hymns, your sermons and thanksgivings, with all your religious parade, and solemnity, are…a thin veil to cover up crimes which would disgrace a nation of savages.

The message was not received. Ball bemoans the deaf ears of the southern white population to the plight of their black compatriots. He highlights other works such as Les Cenelles (The Holly Berries), a poetry anthology by New Orleans Creoles that skewered the claims of superiority to which both petits and grands blancs clung. Cenelles are the fruit of a hawthorn shrub, which Ball describes as “a hardy plant that makes sweet berries in harsh conditions”—a strong metaphor for the creative lives of the Creole authors.

Advertisement

Such a book, had they bothered to read it, might have confounded the prejudices of the Lecorgnes, whose “culture diet” was more given to minstrel shows. In any event, Ball observes, “before the Civil War, there is no air at all for [real] black voices.” Rather, there was white revolt in the air and calls for secession, in defense of a way of life built on the labor of the enslaved.

It was for this reason that Constant, now married and the inheritor of two enslaved people on his mother’s death, volunteered for the Confederate militia at the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861. He was named a captain but soon after was demoted. Aunt Maud’s account in one of her genealogical notebooks reads, “My grandfather Constant joined one unit, but he did not like it much, apparently.” Ball peels back the layers of secrecy to discover that Constant was in fact court-martialed. Along with other recruits, he’d been involved in a violent brawl that turned mutinous and ended with seven killed. He was spared the usual punishment for mutiny, hanging, but had half his scalp shaved clean and was sent home in disgrace.

That humiliation prompted the Lecorgnes, Ball suggests, to buy war bonds to aid the rebel government. Those bonds were put on display in banks downtown, enabling the family to publicly cleanse itself of the stain of Constant’s “resignation” (as it was called in military records). The once-prosperous young couple “mortgage[d] family and future to the great philosophical and moral truth of the superior race.” It was a risky investment that would bankrupt them if the Confederate states lost the war.

In 1862 New Orleans was occupied by the Union Army. “Whites in New Orleans feel panic,” writes Ball, “but no source that I can find names what three hundred thousand enslaved people in Louisiana feel, think, or do during these days.” He speculates that most black people are quietly thrilled: “Gleeful might describe it—but unsure about what is coming.” This absence of primary sources is an obstacle that he must regularly overcome. Ball’s pronouncements on his ancestor come with caveats and qualifications: “I think of his likely words…”; “I suspect Constant…” For missing details of family experience, Ball draws on contemporaneous reports of Louisianans whose age, education, and social standing were similar to the Lecorgnes’ and who kept journals or sent and received letters. There’s the risk that this literary sleight of hand will jar, but the entries, such as Julia Le Grand’s diary in New Orleans, are well chosen. Le Grand serves as a proxy for the imagined anxiety of Constant’s wife:

The suburbs and odd places…are crowded with a class of negroes never seen until the Federals came here, a class whose only support is theft and whose only occupation is strolling the streets, insulting white people, and living in the sun…. This is really the negro idea of liberty.

It was especially intolerable for Constant. He escaped New Orleans and, in a “heroic show of devotion to the cause,” made his way on foot along two hundred miles of curving waterways to reenlist and fight for the rebels. With the South suffering increasing losses, the rebel army committed a number of atrocities, including the execution of three hundred surrendering black Union soldiers at Fort Pillow, in Tennessee. Elsewhere, “paper evidence puts [Constant] in the middle of the revenge killing,” writes his unforgiving great-great-grandson. Ball voyages around his ancestor, drawing incrementally closer with every circumnavigation. Though the evidence is circumstantial, he can see that “Constant’s fingerprints are in many places, even if they are not quite on the doorknob.”

In the aftermath of the Civil War, the white population saw the black soldiers patrolling New Orleans as a threat. The Louisiana Courier expressed outrage: “To see our own slaves freed, armed, and put on guard over us is a deliberate, cruel act of insult and oppression, an exercise of tyranny.” The Civil War was recast as a great calamity visited on the genteel southerners by the formerly enslaved, whom they blamed for the loss of their livelihood and comfortable lifestyle.

In memoir writing, no matter the determination to be modest, authors often struggle to cast themselves as anything other than hero; in Life of a Klansman, Ball travels the other way, entering into the role of villain, challenging his shaky conviction that had he been in his ancestors’ shoes, he’d have acted differently, nobly. He doesn’t have to strive to show Life of a Klansman’s contemporary resonance; the parallels were apparent in the chant “You Will Not Replace Us” by the white supremacists marching through Charlottesville in 2017, advancing the specious notion that they were the true victims, that any challenge to their privilege was an egregious assault on how things ought to be, and that calling out their racism was itself an act of racism.

The most difficult, ghastly, and pitiful chapter of the book, “White Terror,” concerns the rise of the Ku Klux Klan (“the first American terrorists,” writes Ball). Supremacist groups such as the White League (which Constant later joined and which eventually became the Louisiana National Guard) differed from the Klan only in being overt. The Klan emerged as Reconstruction brought the greatest challenge to the old social and political orders, with growing black participation in the democratic process and the elevation of black politicians to positions of authority. The change in the power relations between blacks and whites unleashed a torrent of white fury in the South, which was initially policed though not curbed by the presence of federal troops. Ball writes with great sensitivity about the black victims of appalling atrocities such as the massacre in New Orleans on July 30, 1866, of dozens of black people outside the Mechanics Institute. He believes his ancestor was among the killers, calling it “a blood baptism for him.”

The atrocities were a campaign of attrition that eventually wore down the North and led to the premature withdrawal of Union troops from the southern states. The perpetrators of many of the most heinous crimes were rarely successfully prosecuted and usually not even arrested. Constant was a beneficiary of sympathetic southern officials who permitted terrorist acts to be conducted with impunity, including the failed coup of 1873 and the Battle of Canal Street the following year, when, Aunt Maud recalls, he “had his head split open” in hand-to-hand combat. The terror led to a restoration of white southern rule, buttressed later by discriminatory so-called Jim Crow laws.

Constant adhered to the binary cultural code of America: subjugate or submit. He was seduced by the notion that whiteness, no matter one’s class, always trumped nonwhiteness, a fantasy that would be exploited by grands blancs and their equivalents over the decades. In the 1960s President Lyndon B. Johnson recalled the robustness of the mythic benefits of aligning oneself with the dominant caste: “If you can convince the lowest white man he’s better than the best colored man, he won’t notice you’re picking his pocket. Hell, give him somebody to look down on, and he’ll empty his pockets for you.”

There have been many books on Reconstruction. The great benefit of Life of a Klansman is in showing effectively how its reversal relied on a capacity for delusional justification and thuggery, fueled by a visceral hatred nurtured in the hearts of vengeful men like Ball’s great-great-grandfather. He was a foot soldier in the strategy of intimidation and unspeakable violence, which was designed, wrote L.E. Potts, a white woman who witnessed such atrocities in Paris, Texas, to “persecute” the newly enfranchised black population back “into slavery.”

The effect was lasting on generations of beleaguered black people throughout the South. The Mississippian Richard Wright, whose step-uncle was lynched, wrote about the psychological terror in his memoir Black Boy (1945):

The things that influenced my conduct as a Negro did not have to happen to me directly; I needed but to hear of them to feel their full effects in the deepest layers of my consciousness. Indeed, the white brutality that I had not seen was a more effective control of my behavior than that which I knew.

Ball’s writing is suffused with a generosity of spirit; it has an unusually clear-eyed and quiet quality that often defies the tumult that it is depicting. His humility is palpable as he searches for and interviews descendants of some of those injured or killed in the atrocities that Constant likely took part in. During an interview with descendants of a man shot in the Mechanics Institute killings, Ball admits that his ancestor was probably among the perpetrators; one interviewee “nods at the revelation that a massacre lies on the table between us. It is a bitter dish.” While Ball does not temper his disdain for his great-great-grandfather and his increasingly egregious behavior, he is also able to write with great sensitivity about Constant, a carpenter who on too many occasions had to fashion a coffin for another of his children who died at a young age; he manages to convey the possibility that this perpetrator of evil might also be a candidate for compassion.

Ball has fashioned an intriguing tale around Constant, an ordinary, bigoted man who led an eventful life, with a walk-on part in myriad dramatic events (for ultimately he was not a leader but a follower). He agonizes over Constant’s legacy. Though he wishes to disavow his ancestor, he understands that he cannot: Constant’s violence was carried out on his family’s behalf. Questioning the inheritance of guilt, Ball finds in the Bible “an answer of sorts” and a “nasty forecast” in Isaiah’s book of prophecies: “Prepare a place to slaughter the sons for the sins of their forefathers; they are not to rise to inherit the land and cover the earth with their cities.” In some regards, Life of a Klansman is an act of penance more than an expression of Ball’s belief in the possibility of redemption.

Toward the book’s end, he circles back to the beginning, reflecting on the temptation to scapegoat the original KKK for the violence and sentiments underpinned by white supremacy that are still present today:

It is not a distortion to say that Constant’s rampage 150 years ago helps, in some impossible-to-measure way, to clear space for the authority and comfort of whites living now—not just for me and for his fifty or sixty descendants, but for whites in general. I feel shame about it. That is not a distortion, either. I am an heir to Constant’s acts of terror. I do not deny it, and the bitter truth makes me sick at the stomach.

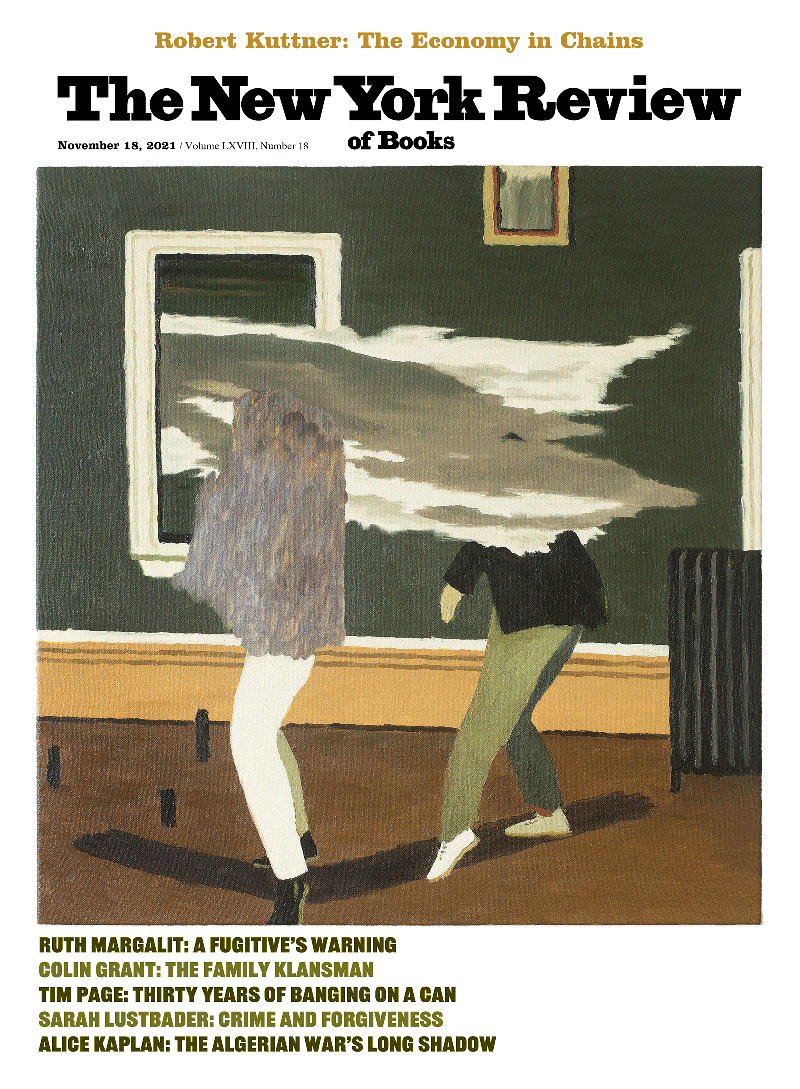

At this moment, in the midst of Black Lives Matter activism in America, any depiction of the Ku Klux Klan comes with the risk of provoking outrage and further trauma. Philip Guston’s 1960s cartoonlike portrayals of fiendish Klansmen were due to be exhibited in 2020 at the National Gallery of Art, in Washington, and subsequently in Houston, London, and Boston. The nervous museums, though, balked and rescheduled the opening for 2024, a time, they argued, when “the powerful message of social and racial justice that is at the center of Philip Guston’s work can be more clearly interpreted.”*

But it doesn’t take much hard thinking to see that the paintings of this white artist satirize the nation’s tacit complicity with white supremacy, and that the depictions of a hooded cigar-chomping Klansman hunting for a black victim or a robed Klansman artist at his easel, as veiled representatives of the average white American, are a provocation, a cultural intervention in the sanctimonious discourse on race. “They are self-portraits,” Guston once said of his KKK paintings. “I perceive myself as being behind the hood.”

Ball, too, perceives himself behind the hood. And he recognizes that there never will be a good time to have the kind of difficult conversations that the National Gallery would rather defer. Life of a Klansman, with its catalog of vile stories, will sicken readers—but necessarily, and perhaps even inspiringly, so; and for that we have the great-great-grandson of a Klansman to thank.

-

*

See Susan Tallman, “Philip Guston’s Discomfort Zone,” The New York Review, January 14, 2021. ↩