In our national debates about criminal justice reform, public defenders have not received as much attention as police and prosecutors. Perhaps this is because their problems seem obvious: they are underpaid and overworked. Defenders tackle insurmountable caseloads by resorting to triage. They hastily review cases assuming that most defendants will waive their right to a trial and plead guilty in order to get a reduced sentence.

It’s true that many defendants want a plea deal. But many others do not consider these agreements a good bargain. For one thing, they typically require probation, which comes with so many conditions that life on the outside can seem nearly as oppressive as a prison sentence. Nevertheless, many defendants accept the prosecution’s plea offer because they cannot sit in jail awaiting trial when family members depend on them, or because they lack confidence that a trial would exonerate them. It’s impossible to know exactly how many feel pressured into pleading, but the number is surely too high, given that around 95 percent of criminal cases in the US end with guilty pleas. State-funded lawyers, who are appointed to represent those who cannot afford private counsel—about 80 percent of criminal defendants—manage the vast share of pleaded cases. For the poor, who are disproportionately people of color, the criminal justice system in the United States is essentially a plea-and-probation system.

The high rate of guilty pleas has consequences that go beyond individual cases. Trials also hold the government accountable; the actions of police and prosecutors come under scrutiny in addition to those of defendants. Pretrial motions, a crucial part of criminal litigation, are opportunities to challenge law enforcement tactics. Even when defendants have committed the charged offense, they may still want to question, for example, whether the police violated their constitutional rights during a stop or search. These motions can be time-consuming for lawyers to argue and judges to decide, but they help maintain the rule of law. When public defenders rarely take cases to trial, the criminal justice system loses an important oversight mechanism.

Reformers have called for increased funding for public defenders’ salaries, staffing, and resources, which are far more meager than the budgets allocated to prosecutors and law enforcement. Three recent books, however, argue that more money alone is insufficient and raise new questions about whether more trials would be enough to address systemic inequality in the justice system.

In 1963 the Supreme Court ruled in Gideon v. Wainwright that defendants who cannot afford a lawyer have a right under the Sixth Amendment to counsel paid for by the states. The unanimous opinion rested on the “obvious truth” that “in our adversary system of criminal justice, any person haled into court, who is too poor to hire a lawyer, cannot be assured a fair trial unless counsel is provided for him.” This was based on the premise that a trial, set up as a contest between two opposing parties, was the best way to determine guilt and guarantee justice—so long as the fight was fair. But the Court in Gideon didn’t require states to spend equally on prosecution and defense, nor did it specify how much states had to spend on lawyers for indigent defendants. Unsurprisingly, states spent very little.

Gideon’s Promise by Jonathan Rapping, a public defender, professor, and MacArthur fellow, takes its name from the nonprofit organization he founded in 2007 to train public defenders. As the name suggests, Rapping wants to resuscitate the adversarial ideal that Gideon espoused, which involves lawyers battling each other before a neutral referee. “Justice,” he writes,

envisions that guilt is determined by a jury, at a trial with a judge to ensure the proceedings meet constitutional muster. And justice depends on the accused having counsel with the time, expertise, and resources to adequately protect their rights throughout the process.

This sort of justice, Rapping laments, hardly exists in the current system, which he describes as a “legal assembly line” or “conveyor belt” on which defendants are ushered from arrest to plea without real guidance.

Gideon’s Promise argues that “real reform” must begin with public defenders, who need to change their “heart and mind” so that they become “true believers” in adversarialism. To explain how defenders can be “change agents,” Rapping relies on management speak, portraying them as leaders who can introduce “a new set of values into an organization”—that is, the criminal justice system. He argues that they can do so as they “speak for” defendants before judges, prosecutors, and the public. Telling their clients’ stories in court, Rapping argues, has “the power to transform” a legal culture that dehumanizes criminal defendants.

Rapping started the Gideon’s Promise organization to prepare law school graduates and new defenders for this culture-changing mission. Headquartered in Atlanta, the training program recruits from law schools and public defender offices in about two dozen states. Rapping accepts only those who show an openness to “change” and “self-critique,” but presumably he’s also picking from a self-selecting applicant pool of those willing to spend the time and able to come up with $20,000 for tuition, which doesn’t include travel costs. (The organization does provide partial scholarships.) Class sizes are small. In its first six years, 228 lawyers graduated from the program. (There were about 15,000 public defenders nationwide in 2007.) Each cohort participates in a two-week “boot camp,” which is followed by semiannual gatherings over three years. Participants learn fundamental defense skills, and, since storytelling is an important part of Rapping’s strategy, they also practice how to “amplify another person’s story” and to use the power of narrative at each step of the trial process, from bail hearing to probation revocation hearing.

Advertisement

But it takes time and money to tell their clients’ side of the story, raising the question of how exactly trainees can apply their lessons in the real world. To illustrate what public defenders can do within the constraints they face, Rapping uses the all-too-common “exploding plea offer” scenario, in which defenders do not have time or resources to verify the government’s allegations or to research relevant legal issues before clients must decide whether to plead guilty or maintain innocence. According to Rapping, in this situation, a public defender should ascertain the client’s priorities and help them make as informed a decision as possible before the prosecution’s offer expires—an example of what Rapping calls the “Close the Gap” method, which entails minimizing “the gap that exists between aspiration and reality” as much as possible.

This is still a far cry from adversarial justice, and it’s not substantially different from what many public defenders already do. Rapping recognizes that public defenders operate “in systems that [are] hostile to good public defense,” yet he focuses primarily on reforming individual defenders, using stories of unacceptable lawyering throughout the book to underscore his points. Lurking behind the scenes is the issue of the overworked lawyers’ mental health. One of the trainees Rapping discusses in his book lasted just thirteen months in the Walton County Public Defender’s Office in Georgia, where she handled approximately 270 cases at a time. Rapping quotes another trainee, who admits, “This work is so hard. I leave these [semi-annual] get-togethers feeling like I can take on the world, and within three or four months I am starting to get beaten down again.” A recent study of eighty-seven public defenders by scholars at Rutgers University and Drexel University provides anecdotal evidence that they suffer significant occupational stress. One spoke of the “trauma of trying to do something different, and have people see my client as a human being, and not be able to succeed in that, more often than not.”1

Although Rapping grants that increased resources and fewer cases are “necessary conditions…to be the public defenders Gideon envisioned,” his book doesn’t focus on systemic reforms, such as the hiring of more defenders, pay and resource parity with prosecutors, and drug decriminalization (which would result in a reduction of criminal offenses and, in turn, caseloads). But even training programs like Gideon’s Promise need money. Any significant change will require government action, and those matters are fundamentally political, not individual or cultural.

Rapping seeks to revive adversarial justice, but what if this idea of justice is too narrow? Adversarialism is not inherent to justice—it’s simply one way of administering it. In Free Justice: A History of the Public Defender in Twentieth-Century America, Sara Mayeux, a legal historian at Vanderbilt, suggests that understanding how “justice” became defined as getting one’s day in court may free us to think about reforms beyond fixing our broken trial system.

Mayeux begins her story during the Progressive Era, when local, state, and federal governments responded to the problems wrought by industrial capitalism by creating new agencies, staffed with experts, to protect public health, safety, and welfare. Reform-minded jurists believed that people dealing with workplace accidents, landlord-tenant disputes, child custody battles, and other social issues needed legal advice—and that the state should provide it. In 1914 John Wigmore, the dean of Northwestern University’s law school, published an article arguing that, just as the state ran public hospitals, it could likewise set up public legal clinics. “Justice,” he wrote, had been “a state function long before health was.”

Wigmore’s proposal caught on with a few lawyers, mainly on the margins of the profession, who supported the idea of government-salaried defense attorneys—the public defender. One was Clara Foltz, the first woman admitted to the bar in California. Another was Mayer Goldman, the son of German Jewish immigrants who grew up impoverished and graduated from the Law School of the City of New York.

Advertisement

In promoting public defense, reformers sought to moderate the excessively combative nature of criminal adjudication, with aggressive prosecutors cutting legal corners and private defense lawyers exploiting technicalities, leading to wrongful convictions on the one hand and the guilty escaping punishment on the other. To remedy this, Goldman argued that criminal defense should become a government function. The state had already taken over policing and prosecution starting in the mid-eighteenth century, so this, Goldman asserted, was the logical next step.

As government officials, both public defenders and prosecutors would, Goldman wrote, “work harmoniously, with the sole purpose of bringing out the facts and the law in a given case, and to strive for the highest ideals in the administration of justice.” Trials would no longer be contentious but collaborative—and rare. Defenders would still go to trial if they believed the defendant to be innocent, but when they thought the evidence was overwhelmingly inculpatory, they would advise clients to plead guilty and to accept a “just and fair punishment.” Progressive reformers viewed plea negotiations not as a symptom of a failing system but as the best way to avoid “petty quibbles” that hired lawyers might raise to thwart the pursuit of justice. Goldman’s early proposals would have given wealthy defendants the option to retain their own lawyers, but he later decided that all criminal defendants, rich and poor alike, should be represented by a public defender in order to eliminate the distortions of the profit motive.

Corporate lawyers, who dominated local and national bar associations, rejected the idea of public defenders. Though they didn’t practice criminal law, they feared that reform in one area would lead to the socialization of the entire practice of law. The influential Association of the Bar of the City of New York dismissed Goldman’s proposal for public defense for the poor as “neither necessary nor advisable.” Most leaders of the bar agreed that poor people needed legal assistance, but they preferred to keep the government out of their profession, arguing that lawyers could volunteer their services and donate to legal aid societies.

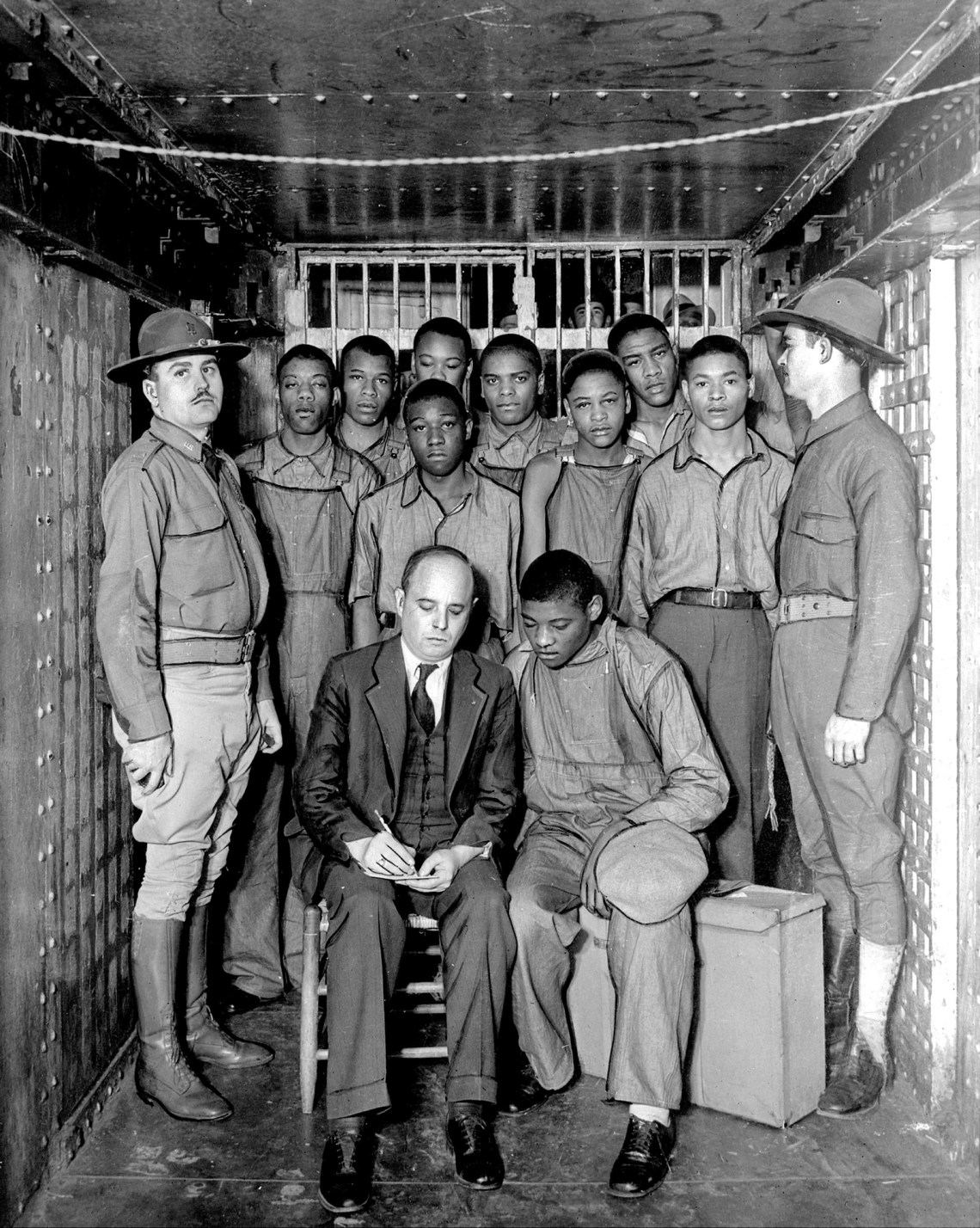

But, according to Mayeux, the Supreme Court’s evolving interpretation of the Sixth Amendment undermined the argument for private funding of indigent defense. When the Bill of Rights was ratified, the right to “the assistance of counsel” had meant that defendants could hire a lawyer if they wished, in repudiation of English law that flatly prohibited counsel in felony trials. The Court began expanding this constitutional right during the Jim Crow era, starting with the 1932 decision in Powell v. Alabama, more familiarly known as the Scottsboro case.

When no active lawyer from the local bar wanted to represent the nine Black teenagers falsely accused of raping two white women on a train near Scottsboro, Alabama, in 1931, an out-of-state lawyer volunteered to take their case even though he did not know Alabama trial procedures and had barely talked to the defendants. The judge separated the case into four trials, each of which lasted just a day, after which the jury convicted and sentenced eight of the nine boys to death.

For the first time, in Powell v. Alabama, the US Supreme Court overturned a state criminal conviction on the ground that the defendants effectively did not have the assistance of counsel. Six years later, in Johnson v. Zerbst, the Court interpreted the Sixth Amendment as not just permitting defendants to hire a lawyer but also requiring the government to provide counsel in federal criminal trials. (The Court extended this right to state criminal trials with Gideon in 1963.) When state-funded counsel was established as a constitutional right, it became difficult to argue that private funders, rather than the state, should pay for it.

Changing tactics, bar leaders accepted public defenders but recharacterized them as a substitute for a privately retained lawyer rather than as a government bureaucrat, as progressive reformers had envisioned. This dovetailed with the ideological imperatives of the cold war. As Americans compared their democratic society with totalitarian regimes abroad, they celebrated the defense attorney as someone who fought for the individual’s rights against the state. And so, Mayeux shows, adversarialism became an all-American, democratic value. As Gideon v. Wainwright declared, “the right of one charged with crime to counsel may not be deemed fundamental and essential to fair trials in some countries, but it is in ours”—a pointed statement about the differences between adversarial trials and show trials, between American democracy and Soviet socialism.

Mayeux argues that the successful reimagining of public defenders had two consequences. First, plea agreements, which progressive reformers had championed as superior to combative trials, “morphed from an aspiration into an epithet,” which highlights how dramatically ideas about both justice and the defender’s duties can change. To be clear, Mayeux doesn’t imply that plea bargaining, as it is practiced today, is a satisfactory way of processing cases. Rather, she argues that a second consequence of this history is that the fixation on adversarialism precluded “a more creative, expansive discussion of what the public defender’s role should be.” Because Free Justice is a historical study, Mayeux doesn’t elaborate what those possibilities might be. But she leaves readers with a provocative thought: If we moved beyond adversarialism, what kind of legal representation could defendants receive?

For Matthew Clair, a sociologist at Stanford University, “effective legal representation alone is not justice.” The goal of the defense attorney in the adversarial system is to obtain an acquittal or the lightest sentence possible. But what if a defendant has another goal, such as proving that the police were motivated by bias? In the current system, defense lawyers try to avoid making unwinnable legal arguments, which might irritate both the judge and prosecutor and be counterproductive to the case or damage their professional reputation. But indigent defendants often view that approach as compromising the attorney-client relationship; it can seem as though the defender is part of the system rather than their personal legal representative. In Privilege and Punishment: How Race and Class Matter in Criminal Court, Clair posits that this mismatch between adversarial justice and defendants’ needs negatively affects not only defendants’ experiences of the court system but also the outcome of their cases, and he questions whether adversarialism actually promotes justice and equality.

Clair studied sixty-three defendants and their lawyers in the Boston and Cambridge municipal criminal courts between 2015 and 2019, tracking how privilege, or its absence, plays out in the criminal justice system. Those who can afford to hire their own lawyer typically trust, and defer to, their counsel’s judgment and consequently are more likely to receive favorable plea deals, drug or mental health treatment, and assistance in future legal matters. By contrast, poor defendants, frustrated with their overburdened lawyers, often take matters into their own hands and end up in even worse predicaments. They write letters directly to the judge or speak out in the courtroom, to the consternation of their lawyers and disapproval of judges. In the eyes of these officers of the court, such defendants are difficult and unruly and need to be silenced. Their lawyers may become even less open to their input, while judges punish their outspokenness.

One of the defendants Clair observed, Tonya, faced revocation of her probation after she failed a drug test. Mollie, her public defender, arrived late to her hearing and did not have time to discuss Tonya’s suggestion that she obtain a letter from a psychologist about her addiction, which Tonya believed would show that she was not culpable for her relapse. Mollie also did not know what could be done about the mouse infestation at the sober house where Tonya was mandated to stay as a condition of probation. In addition, the sober house required too many counseling sessions, which were difficult to schedule around Tonya’s job, which she needed to keep as another condition of her probation.

Instead of listening to and trying to address Tonya’s concerns, Mollie repeatedly insisted that she abide by the court’s orders so as to avoid going back to prison. For Tonya, Mollie was just another “public pretender,” someone who did not, could not, help her because she was “made and paid by the courts.” When Tonya, against Mollie’s advice, spoke up about her addiction and complained about the sober house, the judge extended her probation for two more years and warned her about “wanting to do things your way.”

Other defendants Clair observed, instead of putting up resistance, withdrew from the attorney-client relationship. Some defendants did not show up for court, resulting in arrest warrants for failure to appear. In the Boston area, he explains, the indigent defense system is relatively well funded and its lawyers widely respected; the situation must be far worse in other parts of the country.

Like Rapping, Clair calls for better training for lawyers. But that is not his ultimate goal. Since the norms of adversarialism are contributing to inequality, Clair reasons, the solution is to get rid of everything associated with the adversarial system—including, ultimately, defense lawyers. In the conclusion to his book, he puts forward a slew of reforms toward this aim, ranging from somewhat unlikely to highly unrealistic.

One set of proposals seeks to change the role of the judge, from an umpire who calls balls and strikes, as Chief Justice John Roberts has described it, to a coach. Clair imagines active and socially conscious judges who might permit defendants to voice their concerns and encourage defense lawyers to file motions. This would move toward the inquisitorial system, found in countries such as France, where judges actively participate in the case. In the United States, judges do have some discretion to nudge lawyers and provide defendants with opportunities to speak, but they don’t normally do so in the ways that Clair advocates. And even if they were willing, local trial judges—the ones who oversee the vast majority of criminal cases—face as heavy a docket as public defenders.

Clair also recommends replacing criminal courts with “problem-solving courts” to address issues like drugs and mental health. These alternative courts use a nonadversarial process that

reduces the influence of lawyers…and centers defendants’ interactions with judges and other professionals, such as social workers, who work with defendants to manage the problems presumed to underlie their criminal behavior.

Rather than punishing addiction or antisocial behavior with imprisonment, these courts would prescribe treatment and rehabilitation.

History, however, has shown the dangers of problem-solving courts that don’t have all the due process requirements of regular criminal courts. During the Progressive Era, such courts were said to be “socialized” because they sought to deal with defendants from a social, not just legal, perspective. Juvenile courts, domestic relations courts, and morals courts employed probation officers, social workers, and medical professionals to work with young boys who committed crimes, fathers who failed to financially support their families, and women who engaged in prostitution.

The “therapeutic” treatments they imposed, however, were often punitive, sometimes harshly so. Juveniles may not have been sentenced to prison, but they were still confined in detention homes. Perhaps the most extreme example was the forced sterilization of women deemed “hypersexual,” a policy that received constitutional approval in the 1927 case Buck v. Bell. The abuses of socialized courts led one of its intellectual founders, Roscoe Pound, the dean of Harvard Law School from 1916 to 1936, to reject socialized justice and embrace the old-fashioned virtues of due process.

Clair acknowledges that problem-solving courts can be coercive and punitive. But rather than turning back to adversarialism like Pound, he hopes to eventually “altogether remove the court or any other government authority” from the determination of guilt and punishment, even for violent crimes. In place of the criminal justice system, he recommends restorative justice, such as mediation between victims and offenders and community conferences. Clair offers few details on how this could be achieved and instead briefly mentions a few small-scale experiments that seem promising, such as the “peacemaking programs” operated by the Center for Court Innovation in New York. Given that these reforms appear only in the last few pages of the book, wholesale court abolition may come across as the wishful thinking of an academic.

But shortly after the publication of his book, Clair cowrote an article arguing that because courts “function as an unjust social institution,” “we should therefore work toward abolishing criminal courts.” The article goes on to clarify that abolition encompasses a wide range of reforms that “work toward” the elimination of courts even if they may not ultimately do so. They include the diversion of funding from the judicial system to community organizations like parks and libraries, and community bail funds, which “have shifted power away from judges and prosecutors in determining whether a person is incarcerated pretrial.”2

Clair is clearly inspired by the movement to abolish the police and prisons, which seemed improbable when first proposed in the 1960s and only recently received widespread attention after the murder of George Floyd in 2020. But even a more limited reform like the proposed George Floyd Justice in Policing Act—a bill that does not eliminate policing but would significantly curtail qualified immunity for law enforcement and create a national police misconduct registry—failed in Congress after bipartisan talks collapsed.

Still, assuming that communal, restorative justice programs replace criminal courts (and this is a big assumption), their ability to function without some sort of advocate for the defendant who is not part of the decision-making process would require a utopia in which power relations that marginalize certain groups did not exist, where the “community stakeholders” and “interested parties” that would also participate in the proceedings were neutral. Acknowledging reality—and cognizant of America’s history of lynching Black people, the most horrific example of community justice outside the judicial system—Clair concedes that an institutional process administered by local citizens may require “external accountability…if violent or retributive proposals emerge from community-driven conferences and mediation programs.” He doesn’t specify what that “external accountability” might be, but in the United States it has largely been provided by lawyers who raise legal and constitutional claims in court.

Rapping is correct that the right to counsel is indispensable to individual freedom; Clair is also correct that zealous advocacy in the courtroom is not enough to help indigent defendants find justice. The need for justice comes before the formal beginning of a case, when the prosecutor charges a defendant with a crime, and it continues long after a case ends, in overcrowded and violence-ridden prisons and under probation conditions so onerous that simply keeping a job becomes unmanageable. Injustice exists when impoverished neighborhoods and their schools are overpoliced, when the inability to pay bail means that school-age children or ailing parents have no one to care for them, and when a criminal record precludes good education, housing, and employment. Most people, especially the poor, need a lawyer to advise them through all of these challenges.

In Free Justice, Mayeux provides a historical example of a community-based public defender’s office that sought justice outside the courtroom. The Roxbury Defenders Committee, established in 1971 in a predominantly Black and poor neighborhood in Roxbury, Massachusetts, did fight vigorously for its clients in court. Its lawyers were known for “their eagerness to file motions, take cases to trial, and challenge actions taken by police and prosecutors,” all of which were possible because they strictly limited their caseload. But the Roxbury defenders also advocated for prisoners’ rights, hosted know-your-rights workshops for the community, published a neighborhood newsletter, and broadcast a weekly call-in radio show, as well as running a twenty-four-hour hotline for those who needed to speak to an attorney right away. As Mayeux puts it, the lawyers in the Roxbury office “reimagined the public defender not merely as a substitute for retained counsel…but as a friendly neighborhood resource.” Such legal services go beyond adversarial representation to further both individual and social justice.

This Issue

December 2, 2021

Grand Illusion

‘And I One of Them’

Herring-Gray Skies