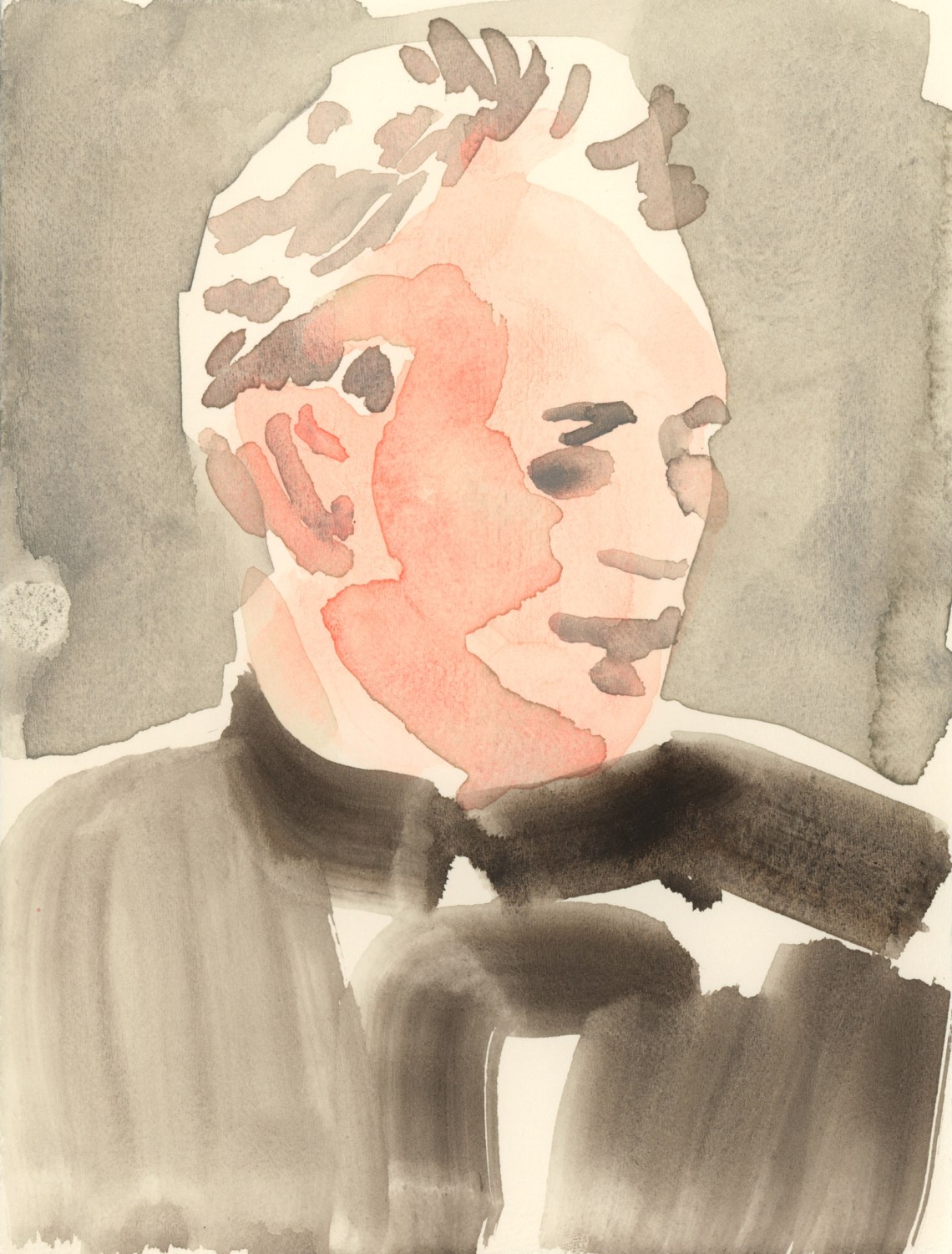

At the very end of Growing Up: The Young British Artists at 50 (2012), an account of the friendships, romances, and working relationships among the students who met at Goldsmiths College of Art in the late 1980s—including Anya Gallacio, Damien Hirst, Gary Hume, Michael Landy, and Sarah Lucas—the art historian Jeremy Cooper reproduces a sketch by Tracey Emin. It is of a man’s head and torso; he is leaning against a wall, one arm bent across his chest, the other disappearing behind his back, like a body preparing to fold in half. Under the portrait Emin has written, “This is My Friend Geremy, Tracy Emin 1997.” Cooper’s note explains:

Tracey Emin’s monoprint portrait drawing of Jeremy Cooper was executed on the spur of the moment in 1997, on one of his visits to the artist’s studio-cum-museum, five minutes’ walk from Waterloo Station. On this particular afternoon Emin was working in the front half of her High Street premises, a gauze curtain pulled across the plate glass window, in an ex-shop which she called the Tracey Emin Museum, with a neatly stored archive of memorabilia in shelved cardboard boxes and work in progress scattered about the place. The monoprint drawing was quickly done in her usual feathery blue line, the reverse-written dedication containing a characteristic spelling error, which may or may not have been deliberate.

The note is typical in its attention to the details of place, circumstance, and artistic method, as well as in the reserved, offstage manner in which Cooper places himself in relation to the story he tells. Growing Up is an intimate collective portrait of a milieu, informed by conversations with the artists over many years, and illustrated with previously unpublished photographs and ephemera that have long been in Cooper’s possession. It couldn’t have been written by an outsider. But the words “I” or “me,” referring to the author, never appear.

Cooper describes Growing Up as an attempt to tell the story of “young men and women [who] found and sustained a desire to make things.” What were these artists like before they became famous? What did they make and how did they make it? To account for how a group of determined students managed to turn themselves into a new artistic generation, Cooper sketches family backgrounds, relationships with teachers, and the various living and working spaces where artists encouraged one another, created work together, made love, or argued. There is nothing here about the investor-collectors who made careers happen (almost no mention of Charles Saatchi, for example), but rather a focus on the local artist-curators who, Cooper implies, made art happen instead.

It is not simply that Cooper regards the fame that came to several of these artists as corrupting and destructive. (He writes sensitively of several suicides, including that of Angus Fairhurst, tortured, he suggests, by his craving for recognition and his simultaneous awareness of its futility.) It is also that for Cooper, celebrity, and the money that comes with it, is fundamentally characterless. What interests him are not the ideas that we have about ourselves and one another but our circumstances, all the varied encounters with people and things that make us who we are. Artistic character, like character in general, is above all, for Cooper, relational, a result of our everyday interactions with our surroundings.

In addition to his biographical study of the YBAs, Cooper has written a number of books about antiques (Victorian and Edwardian Furniture and Interiors) and antique dealing (Dealing with Dealers), two books about artists’ postcards (one the catalog accompanying the 2019 British Museum exhibition of postcards made by artists), and seven novels, the last three of which have been published by Fitzcarraldo. From the varied biographical notes you can learn that Cooper was once a Sotheby’s auctioneer, that he appeared as an expert in the first twenty-four episodes of BBC television’s Antiques Roadshow and copresented the BBC Radio 4 show The Week’s Antiques, that he is a collector of artists’ postcards, and that in 2018 he won the first Fitzcarraldo Editions Novel Prize for his fourth work of fiction, Ash Before Oak. You won’t gather any personal details, such as when he was born, where he studied, or where he has lived or lives now. How he encountered Emin, or Gavin Turk, or any of the artists he writes about isn’t part of the story he wants to tell. Even though his novels are threaded with personal experience, his self-presentation is one of extreme reticence—a habit of self-effacement captured long ago in that early drawing by Emin.

While Cooper is well known on the antiques circuit, it was Ash Before Oak that brought him a wider readership as a novelist. It is a portrait, unfolding through the fragments of a diary, of a man coming adrift from the world. We meet him first after he has decamped from London to the Quantock Hills in Devon, where he renovates a derelict building and records in his journal his observations of goldfinches and owls, his battles with mice. The narrator sums himself up as a person who “can do distance” but who is “not too good at close.”

Advertisement

In general he finds people hard, and especially relationships. As his back-to-nature therapy attempt to anchor himself in the world falters and he slowly begins to fall apart, memories bear down on him. We learn that he is the son of a remote and depressive father, the headmaster of a grammar school; he quotes Nietzsche and Werner Herzog and recalls lectures at Cambridge by the critic Raymond Williams; he recounts art history trips to Italy; he remembers artists he has known, including Gavin Turk and Joshua Compston, the curator and creator of the YBA gallery Factual Nonsense. Compston is the subject of a chapter in Growing Up, and he appears in Ash Before Oak as a friend and neighbor whose body, dead at twenty-five, the narrator discovers in the flat below him:

I am thinking of Joshua. He was so incredibly alive. Maybe too much?

Come and wave to your friends as The real becomes imagined! Come and be on TV!

FN: No FuN without U and fun can seriously make you FN!

Factual Nonsense: he chose a great name for his art gallery. Artists loved the FN bravado. In spring 1996 Gary Hume and Gavin Turk painted his coffin, carried by them and other artists from Charlotte Road to Christchurch Spitalfields for the burial service, accompanied by a jazz band and thousands of mourners, attended by Gilbert and George. I preferred to stay alone at home, two floors above his vacant premises.

Although the journal entries are all couched in the first person, the effect is nothing like an autofictional exploration of the self. Instead the emphasis is all on externals—on the encounters with people, work, and art that shorten the distance between the solitary narrator and the world. Or that may shorten the distance, if you let them.

Cooper’s 2021 novel Bolt from the Blue is also written in the first person, but the voice is divided between the young artist Lynn Gallagher, who leaves home to study at Saint Martin’s in London in the 1980s (over the years of the novel she becomes a notable photographer and filmmaker), and her mother, who is left alone at home in Birmingham. It’s epistolary fiction, although since Lynn and her mother communicate by postcard (Cooper is careful to describe a number of actual artists’ postcards sent by Lynn, such as the Guerrilla Girls’ gagged Mona Lisa, a Peter Kennard photomontage, and several images printed by the political art collective Leeds Postcards), their messages are curtailed and fragmentary in the manner of the journal entries in Ash Before Oak. Here too the subject is distance, measured across time (thirty years), geographical dislocation from the north of England to London, and psychic detachment. The two women battle back and forth between the need to maintain the boundaries of a separate existence in order to have a life at all, and the desire to stay in touch. Art—looking at it, talking about it, sending it in the form of postcards—is the means by which they carry out this self–other negotiation.

Cooper’s new novel, Brian, features another of his solitary protagonists, a man stripped of almost all connection. A man so used to living at a distance, even from himself, that the idea of his writing “I” and “me,” either in a journal or in a letter to another, is unthinkable. The account of Brian’s life is told in apparently “objective” terms by an unseen narrator—judicious, evenhanded, interested in the facts rather than what might be made of them. We first meet Brian when he is in his forties. His mother is dead, and he has lost contact with his father and brother. He lives alone in a rented flat above the Taj Mahal restaurant in Kentish Town in Camden. He works for Camden Council, filing documents recording the transfer of ownership of the borough’s freehold properties. (The narrative begins in the 1980s, when the move from bound volumes to index cards must have felt like a revolution, and several office transformations follow.)

Brian eats his lunch in the same café, run by an Italian family, every day (he arrives late to avoid the crowds), takes his clothes to the same launderette once a week, wears the same dark blue jacket and white shirt on weekdays and weekends, and always takes a bath before bed. It’s a life dedicated to the safety of routine but also—and as a consequence—a life entirely without intimacy, and when we meet Brian he is aware of despair closing in. Almost (but not quite) on a whim, he takes out a membership at the British Film Institute—the cinema and film education institute on London’s South Bank—and the novel is the story of what happens to Brian through film.

Advertisement

What happens has very little to do with plot. Over the years Brian progresses from a film once or twice a week to a film every night, then, postretirement, to two films; he joins the circle of film buffs who gather nightly (almost no first names—these are not friends but BFI regulars who want, indeed need, to talk about the films they have seen); the Museum of the Moving Image that adjoins the BFI closes; Brian gets sent by his boss to join a “public property seminar” in Leeds, and stays for eleven days in a hotel; the launderette winds up its business and he has to find another; he learns to appreciate film scores by listening to Jack, the one BFI regular he begins to think of as a friend.

Sometimes he takes the bus home after the film screenings (mostly the 168) and sometimes the Tube from Embankment to Kentish Town. One of the pleasures for the reader is the precise mapping of London in the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s: the secondhand bookshops that require a dedicated journey, the relationship between Tube and train station at Kentish Town, the University of London Senate House collection of film ephemera that Brian explores on Saturday afternoons, the exact layout of the Southbank Centre. Appalled by the closure of the Royal Festival Hall café for three months, he searches for a place to eat before his evening film and is surprised to find a better alternative at the National Theatre,

down inside beyond the Lyttleton bar…a relaxed seating area and long counter serving reasonable-looking food and snacks.

The next night he went straight from work to the NT café.

And the next.

And the next.

One of the few events in the novel unrelated to film is the July 7, 2005, bus bombing, part of a series of attacks by Islamist terrorists on the London transport network. Brian ends up in the hospital, in a ward with victims of the bombing, and although it turns out that his injuries come from an unrelated accident (he’s been hit by a motorcycle on a pedestrian crossing), he can never forget the people he has seen. Years later when he visits Leeds—where the eighteen-year-old bomber was brought up—he thinks about the boy’s mother and how she survived.

Bus bombing aside, there is no “story” to the novel beyond the story of film. Brian’s celluloid journey takes in the work of Werner Herzog, Yasujirō Ozu, Federico Fellini, Agnès Varda, Robert Bresson, Chantal Akerman, but also Burt Lancaster in The Hallelujah Trail, Charlotte Rampling in Viva la Vie and The Night Porter, Hollywood films, New Chinese Cinema, films starring Alan Bates, and any number of other byways and tributaries. Nothing is not of interest to the amateur film enthusiast, and Cooper enjoys the sheer variety of data that can be gathered with film at its center. (The narrator describes Brian at one point as “a glutton for information.”) Take this gloriously niche sentence: “Jack had been totally taken, he said, by a documentary on the experimental rock group Einstürszende Neubaten and their leader Blixa Bargeld, ace manipulator of the jackhammer in motorway underpasses.” Or: “Masami, in the guise of his one-person band Merzbow, was the most imaginative of all the Tokyo musicians involved in esoteric film scores.” Following a screening of Clint Eastwood’s Tightrope, the narrator notes that

the BFI buffs experienced some of their most vociferous debates around Clint Eastwood, both as actor and director, Tightrope no exception.

Which explained why the post-Tightrope gathering had been noisier than usual, everyone with an opinion. Jokingly, Brian proposed that Richard Tuggle, credited as both scriptwriter and director, was a pseudonym for Eastwood, and was vigorously corrected, as he knew he would be, already aware that Tuggle had written the screenplay of the earlier Escape from Alcatraz.

The short notes on film screenings, and the conversations between the buffs, act as a compendium of film lore, all gathered as in an anthology, or indeed a collection of postcards, with images and information jumbled together to create new connections. Brian’s enthusiasm becomes the catalyst for a new form of collecting (inside his own head, as he ticks off a mental checklist of the films he’s seen), bolstered by the old form of collecting, as he files away program notes in boxes under his bed and hunts for discount copies of books about film:

On his next free Saturday morning Brian visited the cinema bookshop off Ladbroke Grove, with its solid stock of new as well as second-hand books on film, pleased to purchase a copy of Faber & Faber’s screenplay of Dakota Road, as mentioned by the BFI lady. He liked the cover, in line with other paperbacks in the series, designed with a stylized clapperboard above the black-and-white title box. Admiration of this graphic detail had enticed Brian to purchase in the past more Faber film books than he could properly afford. Including the weighty volume of Truffaut’s letters which he had read from cover to cover, all 580 pages. It was comforting, he found, to learn of the French director’s contrariness, unequivocal in the claim that his refusal to learn was as powerful as his wish to know. There was so much of interest to Brian in this series of books. In her preface to Satyajit Ray’s My Years with Apu, the director’s widow wrote of her sorrow at the theft from the nursing home during her husband’s dying days of the altered and expanded version of this posthumously published draft, his annotated text never recovered.

Although Cooper is clearly deeply knowledgeable about the history of film, he offers no theory of the moving image, no account of the meaning of any auteur’s work. Instead, like Brian, he is content to assemble the details of the art form almost at random. It is part of what his protagonist calls the “aesthetic safety gap,” the separation of cinema from everyday life. The last thing Brian wants from film is self-knowledge or personal identification. He prides himself “on seldom taking films personally, pleased to concentrate instead on what appeared to matter to the people making them, to the cinematographer and sound designer as well as director and producer.” Over the years he becomes a connoisseur of Japanese film in particular, and after a three-part screening of Masaki Kobayashi’s The Human Condition, in original prints acquired from the National Film Centre in Tokyo, the narrator tells us:

Brian saw clearly why he was entranced by this period of Japanese movies. Everything about them—the style, the history, the language, the landscape, the story, the meaning, the emotion—was foreign to the British psyche. Unconstrained by the moorings of experience, the West watched the East without expectation.

Cooper does offer some narrative clues to Brian’s fear of the personal. There are hints of a backstory involving infancy in Northern Ireland, abandonment by his father, an orphanage, a mother in prison, a bullied childhood in Kent—although any readerly assumptions about institutions and the Catholic Church prove false when it becomes clear that his parents were Protestants and staunch (“bigoted” is Brian’s word) Unionists. Brian’s childhood has made him “expert at forgetting,” on constant alert for the danger of reminder. He suffers a moment of anxiety following a screening of Terence Davies’s Distant Voice, Still Lives, when during a Q and A Davies tells the audience, apropos his father:

I said to my mother, why did you not just kill him? If it had been me, and this is true, I would have waited until he was asleep and I would have put a pillow over his face. But she was not like me.

However, Brian is relieved to learn that he is able to watch the film with equanimity, that “films on themes and feelings so close to his own story did not necessarily shake alive his stifled memories of the past. He was safe.” He is managing his past rather than coming to terms with it. He puts the art of film in the service of burial rather than self-discovery.

Yet it is “only in the cinema that he became a person,” freed from work, and the routines of everyday life, into the realm of art. Brian’s discovery of himself as an individual (and there is an attenuated friendship plot that I will not spoil) is a consequence not of losing himself in film stories, but of practicing a mode of attention, mixing visual pleasure with intellectual depth. Cooper has given us a kind and tender portrait of a mind engaged with art, to some extent rescued by art, though Brian has no pretensions to being anything other than a lover of film, an amateur curator of art in the heart of everyday life.

In creating a protagonist who is fearful of change (Brian’s mantra is “Keep watch. Stick to routine. Protect against surprise”), Cooper has set himself a challenge. This is a novel that refuses a whole array of fictional conventions, including plot, character development, and even the idea of an inner life. Brian’s lack of interest in self-discovery introduces difficulties for the narrative voice. If the narrator is to give us access to Brian’s worldview, he has to assume more introspection than seems likely in a person determined to avoid feelings because of their disruptive charge. “Brian saw himself as an awkward contrast in character between determined and vacillating”; “if pushed, Brian thought of himself as sexually suppressed in matters of action while opinionated and observant when it came to sex on film.” Encountering sentences like these, the reader feels that Brian has indeed been pushed, by a writer who needs his character to think the things he wants to say.

At one point Brian tries to account for his impatience with theist religion by wondering if he might be a bit of a Buddhist. At another, researching Japanese film, he encounters the work of the agriculturalist-philosopher Masanobu Fukuoka and is “heartened by the old man’s belief in the need to accept insecurity, a life of flight more frightening than staying home to face the danger.” Such references (albeit arcane) are of a piece with the novel’s celebration of ordinariness and anonymity, and its insistence that meaning is the result of repetition rather than change.

It’s a quiet and even melancholic vision, with echoes of another recent engagement with Japanese film: Oliver Hermanus’s Living, a version of Akira Kurosawa’s 1952 film Ikiru, transported to 1950s London in Kazuo Ishiguro’s screenplay. Cooper teeters on the edge of a sentimental ending similar to that of Hermanus’s film (there’s a decision to be made involving a gift). But he resists. Cooper gives us chronology without event, people without relationships, art without identification, agglomeration without purpose. And so we are forced to focus on what’s left—the structure of a life story, mediated through art, but not redeemed by it.

This Issue

November 23, 2023

Inhumane Times

Causes for Despair

Ed Ruscha Bigger than Actual Size