The American Society for Psychical Research still exists. A group of scholars and scientists including William James founded it in 1885 to promote the study of dreams, clairvoyance, mind reading, premonitions, séances, hallucinations, out-of-body states, and other such phenomena. At the time many people in the United States had been caught up in the Spiritualist movement, with its mediums who contacted the dead and reported back. The ASPR wanted to determine whether the mediums were frauds; if they weren’t, could the spirits’ special info, or the cryptic message in a dream, somehow make a person rich? Its archives contain thousands of accounts by everyday citizens who said they had firsthand knowledge of unexplainable psychical occurrences. As the oldest institute for such research in the US, the society has been located at a few addresses, mostly in New York City. Today it is in a town house on the Upper West Side.

When Alicia Puglionesi, a writer with a Ph.D. in the history of science, medicine, and technology, began to work on a book about the society, its staff figured she must be a researcher from a ghost-chasing cable show, of which there are many; apparently the society gets a lot of nonserious inquiries. She e-mailed, called, left messages—no answer. Finally, she took a bus to New York from her home in Baltimore and went to 5 West 73rd Street. After a day of alternately sitting on the steps in front of the locked and iron-gated entry and leaning on the buzzer, she got in. Persuading the society’s president of her seriousness, she was allowed into the archives.

The rule “Be careful what you wish for” always applies. Letters about people’s psychical experiences (especially yellowing, crumbling letters from more than a century ago) tend to be incredibly boring. She was not the first to discover this. Back in the early days of the society James himself was almost defeated by the correspondence: the piles of letters the society received were “a weariness, and I must confess…almost intolerable to me.” But Puglionesi stuck with it. In the book that resulted, Common Phantoms: An American History of Psychic Science, she describes her research as, often, “an aimless drift through the flotsam of the unremembered dead.” This had been the main challenge for the ASPR right along—reading all the mail and making note of what, if anything, the letters contained. As the hours went by, Puglionesi found herself confronting a tedium requiring a “devotion to something beyond the self, something so vast that it can only be glimpsed through the labor of many human lifetimes.”

She seems to have used the pent-up energy to carom into writing a short comic sci-fi novel that came out while her work in the ASPR archives was continuing. Krall Krall tells of the work of Karl Krall, a scientist who wants to start a journal devoted to the thoughts of animals. A main character in the book is Clever Hans, the real-life horse who was said to be able to do arithmetic. Other smart creatures are an African gray parrot that writes “a remarkable paper…on Ovid’s use of the subjunctive” and a large troupe of ants that carries Krall off to witness an ant play or pageant “about the hilariously limited compass of human awareness.” Kudos to Puglionesi for distilling an odd, funny novella out of these unbidden thoughts as she abided with her often tedious research.

William James, in his work with the correspondence, didn’t quit either; if the society only collected enough data, perhaps it would all start to make sense. Democratic ideas inspired him amid the recent upsurge in citizen science. The national Weather Bureau, whose origins went back to 1848, recruited observers in large and small places across the country, asked them to take readings of the weather, and sent forms and instruments to assist them. Thousands of citizens participated; Uncle Oscar recording the temperature and barometer readings every evening on his front porch became a part of small-town life. The observers submitted their figures, and the Weather Bureau compiled them into a national weather map and mailed back copies.

James wanted to do something similar with psychic data. He hoped to be able to create a national map of what people were dreaming about. The society also set up such Borgesian-sounding entities as the Committee on Phantasms and Presentiments, the Census of Hallucinations, and the Committee on Thought Transference. The problem was that people willingly described their psychic experiences but had less interest in documenting and measuring them. The scientific part of the enterprise proved hard to nail down.

Those who ran the ASPR and the public who corresponded with it were of a type: white, Protestant, and middle and upper class (and about evenly divided on gender). Puglionesi says the society disregarded people of color, and as a result it missed psychical phenomena such as the rise of the Ghost Dance religion among Native Americans on the Great Plains. This is a good point. In 1889 a Paiute holy man, Wovoka, who lived in the Great Basin west of the Rockies, had a vision in which all white people disappeared, the dead of all the Indian nations came back to life, and the buffalo returned. He said if the Indians danced long enough and hard enough, this world would come to pass. Imagine if James had talked with Wovoka, or with Kicking Bear, one of the emissaries who brought the Ghost Dance east to the plains. Maybe together they could have helped avert the massacre of the Ghost Dancers and other Lakota at Wounded Knee.

Advertisement

Yet within its demographic the ASPR did reach out. For decades its secretaries, Richard Hodgson followed by Gertrude Tubby and Walter Franklin Prince, responded thoughtfully to letters, trying to coax the writers into recording more hard data about their experiences, such as the phenomena’s witnesses, date, time, place, and recurrences. The correspondents wrote in, trusting that somebody wise would listen to them. That may be why Puglionesi describes the archive as “simultaneously precious and disastrous.” There is so much longing and passion and fantasy and nonsense and wackiness out there. Absorbing even a small amount of what people deeply want to impart to the world is a civic service that also happens to be hard work. The ASPR performed this function as well as anybody could at the time.

By the 1920s the teachings of Sigmund Freud had made the society’s dream studies seem “antiquated,” Puglionesi says. Any idea of a national map of dreams evaporated with the popular acceptance of Freud’s theory of them as individual phenomena driven by the repressed sexual drives of individual dreamers—a catchier approach to psychical study than anything the scientists at the ASPR had come up with. They were thinking in terms of a national unconscious, and sex didn’t enter into it. Their studies had hit upon nothing solid; they were still waiting for patterns to emerge. Puglionesi says that the society’s experiment in psychical research failed and that its enterprise “no longer exists, for practical purposes.” Today people with liminal psychic experiences can find and support each other on the Internet.

Puglionesi regretted that the story of the ASPR wasn’t somehow more dramatic or conclusive, but she accepted it. Of the organization’s legacy, she said, “I feel closest to those who wondered, experimented, and then traveled on through the world not beholden to the desire for certainty.”

Her next book, In Whose Ruins: Power, Possession, and the Landscapes of American Empire, tells a story that is more clear-cut. Common Phantoms describes a country full of lonesome folks with dreams and psychical experiences to share. In Whose Ruins, by contrast, talks about race fantasies common among members of the same broad demographic—fantasies that damaged the environment and abetted genocide. No villains trouble Common Phantoms. The villains in In Whose Ruins are white people, an unum whose pluribus appears variously as “white Americans,” “white men,” “white settlers,” “the white man,” “white visitors,” “ordinary white people,” “white consumers,” “white professionals,” “white travelers,” “white artists,” “white collectors,” and “white people boating in a reservoir.” Sometimes they are referred to simply as “they” or “them.” Puglionesi quotes Barbara Smith, the queer Black feminist, who wrote, “We have been on to the white man and his poisonous capacity for ruin for centuries.” In other words, the book is not likely to become required reading in the public schools of Florida, Oklahoma, or Arkansas anytime soon.

Which will be their loss, because In Whose Ruins explores some fascinating, haunted places. Puglionesi looks at four sites that were plundered of resources or history or both, as the resident Native Americans were (or had already been) driven out, killed, made ill, or robbed of their cultural past. One persistent and popular theory ran through much of the thievery and claimed to justify it. William Cullen Bryant even wrote a famous poem, “The Prairies,” that in 1832 made the theory into a rose-tinted myth. Supposedly an ancient race of white people inhabited North America before the ancestors of the current Native Americans. As the fantasy was retold, other writers, naturalists, local boosters, and skull-collecting ethnologists described these notional First Americans as Danish Vikings, Celts, Phoenicians, Assyrians, Hebrews, Romans, Druids, Toltecs, or refugees from Atlantis (that presumably all-white lost continent).

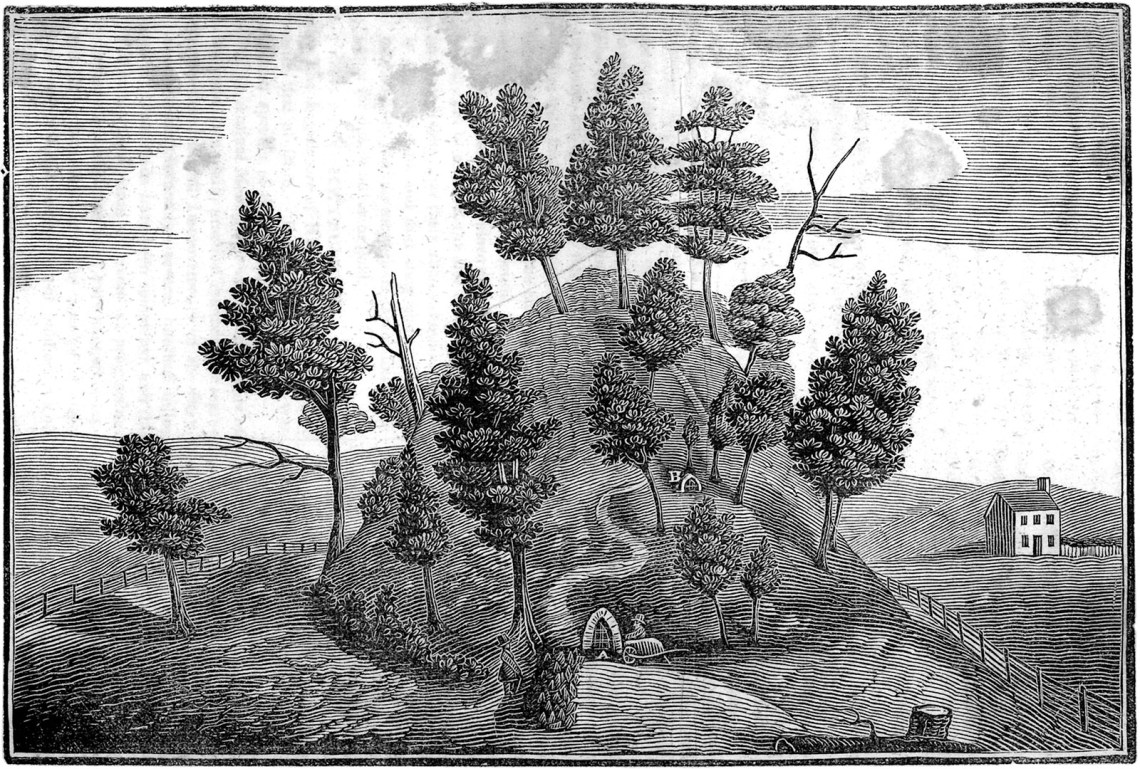

The first plundered place Puglionesi looks at is the Grave Creek Mound, on the Ohio River in what is now West Virginia. Locals dug a tunnel into the sixty-foot-high mound in the late 1830s at the behest of its then owner; he added a gift shop and made the mound a riverside tourist trap. Archaeologists say the mound was built by the Adena people, an early Native culture, more than two thousand years ago. Thousands of ancient human-built mounds and other earthen structures can be found in Ohio, West Virginia, and other states in the Mississippi watershed. The ancestors of modern Native Americans almost certainly built them; Indians in more recent times were still burying their dead in mounds. But if, as the white Mound Builders theory claimed, a race of Danish Vikings (for example) had built them, and their descendants were no longer here, then the ancestors of the resident Indians must have come from somewhere and wiped them out; therefore, the Danes’ recently arrived fellow white people would be justified in wiping out the Indians.

Advertisement

Civic leaders said that inside the Grave Creek Mound the diggers had found a stone inscribed with twenty-four characters in an unknown language. The stone appears to have been a fraud intended to raise money for the dig. In 1842 Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, purveyor of tales acquired from his part-Ojibwe wife—tales that inspired Longfellow’s popular “The Song of Hiawatha”—sent a drawing of the stone to scholars in London. It got them excited; they speculated that the writing might be Celtic, Phoenician, or Hebrew. Schoolcraft thought it was “Druidical runes.” An authority from the Smithsonian Museum called the stone a fake, but the white Mound Builders myth persisted. Of its empire-creating purpose, Puglionesi says, “Controlling the past and the story of origins is essential to controlling the future.” In this case, the myth’s suppositions were used to justify the theft involved in Manifest Destiny.

From the Grave Creek Mound, Puglionesi goes about 150 miles northeast, to western Pennsylvania, site of the world’s first oil boom. Oil was so plentiful there that it seeped from the ground. Native Americans had dug pits as deep as ten feet, lined them with timber to collect the seeps, and used the oil for medicine and trade. The Seneca, one of the six nations of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, still had large holdings of land in the region in 1859 when Colonel Edwin Drake, who wasn’t a colonel, drilled the first commercially successful oil well, near Titusville. The rush that followed gave a preview of the suicidal modern world.

Drillers widened their well bores with nitroglycerin torpedoes that set towns on fire. A gusher came in, caught fire in the air, rained down, and burned seventeen people to death. Sellers dumped oil in creeks rather than accept a too-low price for it. One observer estimated that three fourths of all the oil produced in the region was wasted. In terms of environmental damage, Puglionesi says that the California Gold Rush of 1849 had attracted similar hordes of fortune seekers, but “the forty-niners were artisans compared to the oil operators.” The Seneca had to struggle to hold on to any of their land and oil, partly because the imaginary white Mound Builders’ prior claim, cited by boosters of development and writers of made-up local histories, was thought to weaken theirs.

Again, the spirits of the dead got into the act, tipping off select Spiritualist mediums about where drillers should drill, based on the spirits’ private intel from long ago. The white Mound Builders had probably dug the oil pits originally, too, folks said. During the full-blown rush, Spiritualist dowsers also sought the help of vanished Indians like Squanto, Pocahontas, and Sacagawea, and spoke in alleged Indian languages as they rapturously dowsed. And all this to bring light to the world: for half a century, the purpose of the oil was not to power automobiles but to fuel kerosene lamps, the country’s main source of artificial light after 1850.

A lot of stuff blows up in this book. From the antique oil patch, the story moves to the valley of the Susquehanna River in Maryland in the 1920s. Before the Conowingo Dam flooded this section of river, Dr. Francis Nicholas, dean of the Maryland Academy of Sciences, dynamited a giant rockface covered with ancient petroglyphs. He and his team blasted more than ninety pieces from the surrounding rock, fished them out of the river, reassembled them, and put the best of them along the walkway to the Academy in Baltimore. When the organization was forced to sell its building in 1944, it shipped the petroglyphs to a public park, where they were forgotten. No one knew who made the petroglyphs, but the continent-deprived refugees of Atlantis again were suggested as a possibility. Archaeologists today think that the images carved in the rock—interpreted as fish, turtles, snake heads, boundary markers—might be four thousand years old.

The Conowingo Reservoir, the lake created by the dam, is one of many impoundments that drowned Native American sites in the dam-building years of the twentieth century. Three hundred years earlier, the Susquehannock Indians had occupied the valley. Long gone from the riverbanks by the 1920s, they did not have to move to escape the reservoir, but other dams displaced Native people around the country. This happened while the government was also trying to terminate the tribes and get their members to integrate into white society. Another justification for building the dams was recreation—that was where the “white people boating in a reservoir” came in.

Drowning history and replacing it with false stories more congenial to a government’s own fears and desires—one can see the usefulness of that for making an empire. But exactly how the magic works in every instance can be hard to follow. Describing how empire building, erasure, and white supremacy made use of the Conowingo petroglyphs, the author says:

Just as the dam produced power by spinning the poles of a magnet around a copper coil, the petroglyphs’ power came from rapid oscillation in meaning. They were Indian and non-Indian, primitive and civilized, mundane and exalted, all at once.

I’m not sure what that means, but her larger point—that the petroglyphs should have been left alone, undrowned and in situ, in all their unknowability—one can understand and agree with.

In the Southwest, the fourth place Puglionesi looks at, the destruction rises to the level of apocalypse and million-year contamination. Linking the four places was a challenge. From the book’s subtitle, “Power, Possession, and the Landscapes of American Empire,” a reader might not guess that the real theme is the damage white supremacy did to Indians and their land. By the 1940s, when the nuclear age began, the fantasy about an ancient white race inhabiting North America had faded, and a dreamy, idealized picture of Native people had taken over. Artistic types and others seeking the continent’s ancient wisdom went to Arizona and New Mexico hoping to learn the Southwestern Natives’ ancient-modernist simplicity and sense of beauty before all the Indians died off or disappeared, which Teddy Roosevelt and other thought-leaders of the day expected them to do eventually.

As a teenager, Robert Oppenheimer spent time in New Mexico for his health, and he loved the area, which was one reason he proposed Los Alamos as a field-test site for the Manhattan Project. The military’s bomb-builders showed a heedlessness toward the inhabitants, who included the Pueblo people, some of whom lived in the oldest continuously occupied villages in North America, as well as Spanish-speaking farmers who had also been there for generations. At the beginning of the project nobody really knew what radiation did to living tissue, but with a war going on, the US government exposed people without finding out or warning them. Test explosions at the Trinity site 210 miles south dispersed radioactive fallout widely, and the labs dumped toxic waste that affected places where locals drank the water and grew crops and raised livestock.

Generations later, cancers are common among the descendants of those residents, many of whom died of cancer themselves. Puglionesi tells us that the partial meltdown of the reactor at Three Mile Island was only the second-worst nuclear disaster in US history. The worst was the release in 1979 of 95 million gallons of radioactive slurry from a uranium mill dam into a Diné (Navajo) farming community on the Rio Puerco in New Mexico.

Some of the scientists at Los Alamos relaxed in their off-hours by learning about Native culture. A few became ethnographic experts, studying styles of pottery and exploring Pueblo ruins (which only appeared to them as ruins; Hopi and other Native people were still visiting them and using them in unrevealed ways). Considering the weapons the scientists built, Puglionesi does not let these enthusiasts off easy: “Their acquisitive curiosity looks, in retrospect, rather like the desire of the guilty to possess innocence.”

After describing the “environmental, racial, and economic violence of the nuclear complex,” Puglionesi reminds us that it “wasn’t the beginning of the story” in the Southwest because the bohemian appreciators came before. Willa Cather was one of the artistic visitors (D.H. Lawrence, Ansel Adams, and Georgia O’Keeffe were others) who found inspiration in the Native culture. Her novel The Song of the Lark is about an opera singer who goes to a ranch “near a Navajo reservation” and in a trance imagines the Pueblo women who made the beautiful ancient water jars she has seen. Moved by this vision, she dedicates herself to singing in a renewed and truly American voice, with which she proceeds to wow audiences in Europe.

This narrative “of white arrivals strengthened by mingling their voices with the echoes of the Native past,” says Puglionesi,

would help bomb makers enjoy Pueblo art without worrying about the fate of their [local Native] cooks and maids. It allowed cultural appreciation to run on the same frictionless mental machinery as algorithms of death, metabolizing the ceremonial kiva [an underground chamber] into a space for nuclear fission experiments.

That is, the appropriative fantasies white people directed at Native Americans were kin to the state of mental abstraction required to build weapons that could blow up the world. The book’s white villains do have a lot to answer for, but drawing a line that connects Willa Cather to the atomic bomb seems a stretch to me.

Radiation poisoned some of the Los Alamos scientists, too. The project’s Health Division kept track of the staff’s radiation exposure and tried to limit it, but could do only so much in the circumstances. Puglionesi describes a horrible accident in which a group of scientists were bringing a nuclear reaction to the brink of criticality—“tickling the dragon’s tail,” this was called—when an experimenter’s hand slipped, parts that shouldn’t have touched did touch for a split second, and a huge dose of radiation was released into the lab. Louis Slotin, who was holding the part that slipped, half-shielded Alvin Graves, who was standing behind him. The unshielded part of Graves’s face was grotesquely distorted by the exposure. The author uses this as a metaphor for the two faces of nuclear energy, the “terrible” face being its dread power as misused by the white-supremacist USA.

Graves survived; a reader wondering if somehow Slotin did too must pay close attention, because the author omits specific mention of his fate until eight pages later, when she refers to “the shadow of his [Graves’s] dead colleague burned onto his [Graves’s] body.” The confusing description serves to underplay what happened. We are to understand that both Slotin and Graves are privileged white men—i.e., the bad guys. She says, “The face of misfortune rarely turns on men like Slotin and Graves.”

Louis Slotin was thirty-five years old, from Canada. The army flew his parents to Los Alamos from Winnipeg. An estimated 15,000 rems of X-rays had hit the hand that slipped, and around 2,100 rems of gamma rays, X-rays, and neutrons radiated the rest of his body; a dose of 500 is usually fatal. The hand blistered, swelled up, and turned blue. It was packed in ice. After nine days of more physical disintegration and suffering, he died. His body was flown to Winnipeg in a sealed coffin. We are given none of that follow-up; some empathy on the author’s part would have been in order here.

In the end, both In Whose Ruins and Common Phantoms are about the American search for treasure. Spirits of the dead whom the mediums consulted maybe knew where treasure was. It hid in the landscape, and in the ferment of the country in the later nineteenth century, when people were staying up late and cogitating by the new, cheap light of their kerosene lamps. An invention could be a treasure, too. Applications at the US Patent Office went from 785 in 1840 to more than 21,000 in 1875.

Among the ASPR’s psychical goals, it wanted to discover where the recent boom in American inventive genius was coming from. Dream-inspired treasure strikes, in the ground or in the mind, could redeem the programmed unfairness of capitalism—as Puglionesi puts it, “literally spinning dreams into gold.” The Grave Creek Stone, with its spurious proof that white people were the earliest Americans, bestowed a false and cruel power to steal treasure in the form of land. The power of the atom—an archvillain’s treasure, fiercely pursued so that archvillains wouldn’t get it first—topped the list of treasures and did the most lasting damage. Puglionesi ends In Whose Ruins:

So many of our stories dance around the horror of a treasure that is cursed, and the fear of letting it go. The point is to see that not as ruin, but as life itself.

If the last sentence means that salvation lies in letting go of the treasure, I’m with her, but I don’t think it will happen. A recent Power Ball Pick Six Lottery topped out at $842 million, and there are people with metal detectors digging in the sand on Coney Island right now. Of the two books, I prefer the less plot-driven Common Phantoms, for its strangeness, lonesomeness, and lack of conclusions. It’s about a hapless kind of hope out of control—like the Wizard of Oz making a stirring speech at the end of that movie and then going up in the balloon, yelling, “I don’t know how to stop this thing!” and leaving Dorothy behind. In Whose Ruins indicts us, but Common Phantoms in its essence is funny and sweet. The US is a funny country, maybe the funniest in the world. We’ve got that going for us, anyway.

This Issue

February 8, 2024

Who’s Canceling Whom?

The Bernstein Enigma

Ethical Espionage