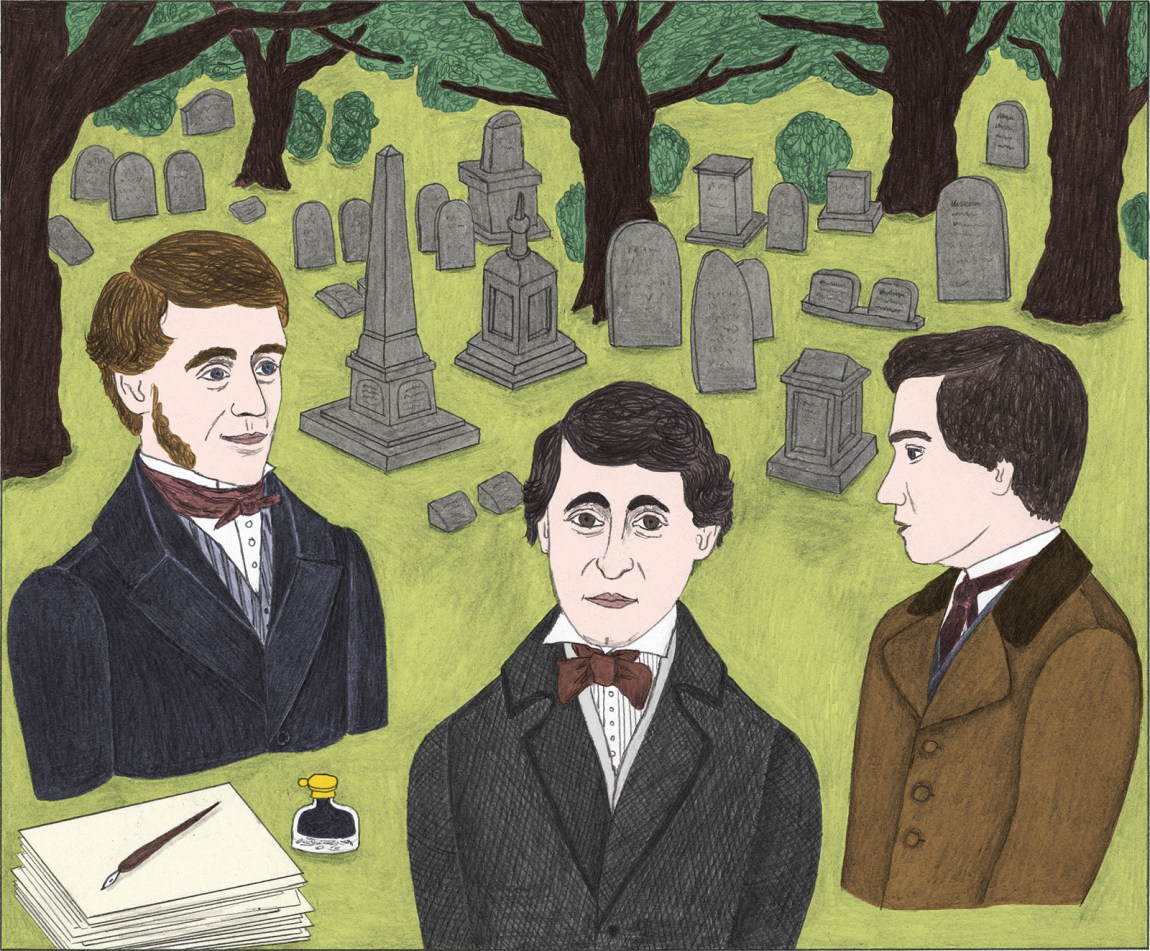

The effect of this little volume, which looks hardly more than a pamphlet, is wholly out of proportion to its modest dimensions. Robert Richardson died in 2020 at the age of eighty-six, and Three Roads Back is a fitting coda to his greatest achievement: the trio of biographies of Henry David Thoreau, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and William James that he published between 1986 and 2006.1

Richardson’s lengthy subtitle here, “How Emerson, Thoreau, and William James Responded to the Greatest Losses of Their Lives,” refers to the bereavements that, similarly and remarkably, all three men suffered in their early adult years. Emerson’s first wife, Ellen, died of tuberculosis in February 1831, when she was nineteen and he twenty-seven. Her last words on her deathbed must have afforded him a grain of comfort: “I have not forgot the peace and joy.” As Richardson wrote in his biography, Emerson’s “heart was with the dying, but Ellen’s was still with the living.”

On New Year’s Day 1842, in Concord, Massachusetts, Henry Thoreau’s brother, John, cut a finger while shaving. Ten days later he died in his brother’s arms of lockjaw—tetanus—following on the seemingly trivial wound. He was twenty-seven, and Henry was twenty-four. Afterward Henry wrote to a friend that his brother “was perfectly calm, even pleasant while reason lasted, and gleams of the same serenity and playfulness shone through his delirium to the last.” Richardson suggests that “Henry was putting a good face on a scene that was not all calm and serene.” Indeed, by all accounts death from lockjaw was in those days inevitable and agonizing.

The tragedy experienced by William James—who was born on the day that John Thoreau died—is more ambiguous than those that befell the other two great thinkers. In the summer of 1868, at the age of twenty-six, he was sunk in depression. In his diary, addressing himself in the second-person singular, he spoke of wanting to die, since “with you there are so many things that lead to nothing and which are nothing but disgusting.” Not quite two years later, he was still sunk in despair when, on March 8, 1870, his cousin Minny Temple died, like Ellen Emerson, of tuberculosis. She was twenty-four.

Minny, the daughter of Henry James Sr.’s sister Catherine, was a singular young woman, as her surviving letters and the recollections of those who knew her attest. Both William and Henry James were in their different ways smitten with her, and her memory remained with them until the end of their lives. As Richardson and others have recognized, there is much of her in a number of Henry’s major female characters, notably Isabel Archer in The Portrait of a Lady and the eponymous heroine of Daisy Miller, while Milly Theale in The Wings of the Dove, who is destined to die young, even bears the same initials.

In his memoir Notes of a Son and Brother, published in 1914, two years before his death, Henry wrote of Minny:

No one felt more the charm of the actual—only the actual comprised for her kinds of reality…that she saw treated round her for the most part either as irrelevant or as unpleasant. She was absolutely afraid of nothing she might come to by living with enough sincerity and enough wonder.

Writing to his brother, Henry observed that while everyone was taken to be at least partly in love with Minny, “I never was”—hardly surprising, given his undisclosed sexual inclinations—“& yet I had the great satisfaction that I enjoyed pleasing her almost as much as if I had been.”

The two James brothers were not the only ones to fall under the charms of Minny’s personality. The future jurist Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. and the successful Boston lawyer John Gray were also dazzled by her. Some lines of a letter from Minny to Gray, quoted in Richardson’s biography of James, give a glimpse of her energy and joie de vivre:

We all went on a spree the other night, and stayed at the Everett House: from which, as a starting point, we poured ourselves in strong force upon Mrs. Gracie King’s ball—a very grand affair, given for a very pretty Miss King, at Delmonico’s.

To the young men who were her admirers, however, what was of far more consequence than her appetite for parties was her intellectual adventurousness and her wholly unsentimental empathy with the trials and tribulations of other people. Writing to William James just two months before her death, she declared:

A thousand times when I see a poor person in trouble, it almost breaks my heart that I can’t say something to them to comfort them. It is on the tip of my tongue to say it, and I can’t, for I have always felt the unutterable sadness & mystery that envelopes us all.

Despite the sorrows experienced by Richardson’s three subjects, and despite the passion and beauty of their written accounts of those sorrows, there is another, more subtle aspect to the matter. Emerson, Thoreau, and the two Jameses had in common what is surely a characteristically nineteenth-century American sensibility when it came to tragedy and loss. Even while they suffered, they kept in clear view the fact that in time, and in a not very long time, their suffering would come to an end, or would at least be subsumed into the everyday pattern of life. Here is Henry James writing to his brother of Minny’s death:

Advertisement

Her presence was so much, so intent—so strenuous—so full of human exaction; her absence is so modest, so content with so little. A little decent passionless grief—a little rummage in our little store of wisdom—a sigh of relief—and we begin to live in ourselves again.

This might be seen as the articulation of a stoical approach to the death of a beloved young woman, but on a harsher view it could be taken for plain coldness of heart. Richardson, tellingly, ties this letter and its tone to the famous passage in James’s great late novel The Ambassadors in which the prematurely aging Lambert Strether urgently advises a younger man, Little Bilham: “Live all you can; it’s a mistake not to.”

Minny’s death, Richardson quietly points out, was not an event that led Henry James toward a new beginning: “It was a loss, plain and simple.” But it was a loss that endured—James devoted the long last chapter of Notes of a Son and Brother to Minny and her early death and what it meant, and continued to mean, to him. Yet even in this muted threnody the novelist remains clear-eyed and honest, as all artists must be in acknowledging how they adapt the stuff of lived life to the needs of their work. If the loss of Minny “appeared so of the essence of tragedy,” James knew that he would “in the far-off aftertime” seek to “lay the ghost by wrapping it…in the beauty and dignity of art.” The dead Minny would become the living Isabel Archer, Daisy Miller, Milly Theale…

The bond between William James and Minny was strong but hard to classify. Richardson suggests that romance would hardly have been a component of it. Yet they were very close and treated each other as intellectual equals. They also shared a deep interest in religious experience, a subject on which William was to write extensively. It seems highly unlikely that Minny regarded him as a marriage prospect—or anyone else, for that matter. As she wrote wittily to John Gray, “I am aware that if all other women felt the eternal significance of marriage to the extent that I do, that hardly any of them would get married at all.” William, meanwhile, noted baldly in his diary that “Nature and Life have unfitted me for any affectionate relations with other individuals.”

In the month after Minny’s death, William passed through what was undoubtedly the most serious spiritual crisis of his life. One twilit evening he experienced a ghastly “revelation,” when “there fell upon me without any warning, just as if it came out of the darkness, a horrible fear of my own existence.” However, the event, frightful though it was, marked the breaking of a yearslong nervous fever. A few weeks later he made that well-known—and funny—declaration in his journal: “My first act of free will shall be to believe in free will.” He went on to posit the belief, though it “can’t be optimistic,” that “the real, the good” of life is achieved “in the self-governing resistance of the ego to the world.” This conclusion, Richardson contends, “is the central insight, the pivotal moment of William James’s life.”

A far more startling example of intellectual resilience—and Resilience, we are told, was an early title of Richardson’s book—is that famous, not to say notorious, passage in Emerson’s essay “Experience” in which he recalls the death of his five-year-old son, Waldo, in 1842. The father was devasted by the child’s death—“Shall I ever dare to love anything again?” he asked in a letter to his friend Margaret Fuller—but in the essay, written two years later, he displays what some readers at least will consider an eerie cold-bloodedness.

He grieves “that grief can teach me nothing, nor carry me one step into real nature,” and observes that in Waldo’s death “I seem to have lost a beautiful estate—no more.” If tomorrow news should come that his chief debtors had gone bankrupt, or that his property was lost, it “would be a great inconvenience to me, perhaps, for many years; but it would leave me as it found me,—neither better nor worse.”

Advertisement

So it is with this calamity: it does not touch me: some thing which I fancied was a part of me, which could not be torn away without tearing me, nor enlarged without enriching me, falls off from me and leaves no scar.

Richardson does not allude to this passage, but he does mention the hardly comprehensible venture Emerson made into the land of the dead on March 29, 1832, just over a year after his wife’s death, when he visited her burial place at Roxbury. During the previous year, he had walked there from Boston almost daily. This day, however, was different. He had the coffin opened so that he might view the remains. It was a thing not unheard-of at the time, but it must strike us as ghoulish in the extreme.

Richardson, in his biography of Emerson, offers a different interpretation: “He had to see for himself.” In the year since Ellen’s death, her husband had been behaving as though she were still alive, holding her image firmly before him and addressing her directly in his journal. Now was the time to have done. As Richardson wrote, “He would live no longer with the dead.”

His concern from now on would be the world as it is, not as religion would have it be. “I regard it as the irresistible effect of the Copernican Astronomy,” he wrote, “to have made the theological scheme of Redemption absolutely incredible.”2 A week later he resigned as a junior minister of Boston’s Second Church. He was now the man who would write what Richardson is not alone in considering his finest book, Nature (1836), and the series of essays, lectures, and addresses including those three masterpieces, “Experience,” “Self-Reliance,” and “The American Scholar.”

It was in Europe, and not in his homeland, that this quintessential American thinker experienced an epiphany that was to form the basis of what we might call his aesthetic, a frame of mind that would guide his thought and work for the rest of his life. In December 1832, almost two years after Ellen’s death, he embarked for Europe on what could be called—though this vigorous democrat would likely not have called it this—a Grand Tour. He was in no condition for such a venture, being in extremely poor health, both physical and mental. After he had endured a terrible week at sea—“nausea, darkness, unrest, uncleanness”—the weather improved, and so did he.

After another four weeks on shipboard, during which, as Richardson writes, he developed a “newfound respect for experience as opposed to mere words,” Emerson landed in Malta, then moved northward through Italy and Switzerland, arriving in Paris in midsummer. There he visited the Jardin des Plantes and discovered to his delight the richness of the natural specimens on show: “It is a beautiful collection and makes the visitor as calm and genial as a bridegroom. The limits of the possible are enlarged.”

Richardson takes those mentions of calmness and geniality as a sign that Emerson had at last recovered, or at least was on the way to recovery, from the death of his wife and the anguish it caused him. Struck by “the upheaving principle of life everywhere,” he wrote, with wonderful and characteristic delight, “I feel the centipede in me, cayman, carp, eagle and fox.” Those days in the Jardin des Plantes brought out the “naturalist” that he had determined to be when he turned away from organized religion.3

Less than a month after his return to Boston, Emerson delivered his first public lecture, “The Uses of Natural History.” He spoke of his discovery in Paris of “a grammar of botany” and invited his audience to “imagine how much more exciting and intelligent is this natural alphabet, this green and yellow and crimson dictionary, on which the sun shines and the winds blow.” He also identified the “secret sympathy which connects men to all the animals, and to all the inanimate world around him.” He had pledged himself, Richardson writes, to the green world. Christ he would reject as lacking cheerfulness and love of nature, kindness, and a feeling for art.4 He had put a wide distance indeed between himself and the pulpit. Richardson writes:

Regeneration, not through Christ but through Nature, is the great theme of Emerson’s life, and it came to him as a response to the death of his young wife Ellen. Emerson uses the language of redemption, regeneration, and revelation—terms for what we would now call resilience.

Thoreau, too, following his brother’s painful and untimely death, embarked on the program of becoming what he was determined to be. These were hard times in Concord. Eleven days after the loss of John, Thoreau developed symptoms of lockjaw himself, though it soon became apparent that it was only—only!—a sympathetic reaction. This was five days before little Waldo Emerson succumbed to scarlet fever, a disease for which there was no cure at the time. It must have seemed as if the angel of death had pitched his tent in that small New England town and meant to stay.

But for Thoreau there was life still, which behooves us to live it, and live it to its fullest, as Lambert Strether insisted. Who can say what torments of sorrow and bereavement Thoreau had to endure in order to come through to the other side? But come through he did. In March 1842, after that terrible January in which his brother and the Emersons’ child perished, Thoreau, in journal entries and a long letter to Emerson’s sister-in-law Lucy Jackson Brown, set about hauling himself up from the abyss of despair.

“What right have I to grieve,” he writes, “who have not ceased to wonder?” The world—nature—simply will not have it that we should give up our vivacity because others die, have died, will die. “Soon the ice will melt,” he declares, and the blackbird will be singing again along the river where his brother used to walk. “When we look over the fields we are not saddened because these particular flowers or grasses will wither—for their death is the law of new life.” As Richardson parses these sentiments, “Individuals die; nature lives on.”

Thoreau’s essential insight, Richardson writes, “is that we need an anti-anthropomorphic, nature-centred vision of how things are.”5 Richardson sees this, along with two other crucial realizations—that “our intellectual connections and our friendships actually matter more than family,” and that despite the deaths of individuals “the natural world as a whole…is fundamentally healthy”—as marking “the sudden emergence of the greatest American voice yet for the natural world, a world including—but not centered on—us.”

In this book, Richardson knows whereof he speaks. In her foreword, Megan Marshall, another superb biographer and the author of Margaret Fuller: A New American Life (2013), notes that when he was a college student he lost his younger brother John—another John, doomed like Thoreau’s sibling of the same name—who died of leukemia at the age of seventeen. Yet Three Roads Back, as Marshall is quick to point out, is as far from a self-help manual as it could be. Richardson was well aware that, as William James pointed out, “tragedy is at the heart of us,” yet James had a further twist to that seemingly bleak formula: “Go to meet it, work it to our ends.”

Three Roads Back is not only a consideration of the thought and actions of a group of singular historical figures: it is also a treatise for our time. Richardson’s measured celebration of the resilience of the human soul “is not,” as he says of Emerson’s account of his recovery from grieving, “just happy talk or routine uplift or marketable optimism.” The world is as the world is, and its chief object is to endure. At the close of his brief book Richardson quotes a passage from Emerson’s essay on Montaigne in his Representative Men (1850):

Although knaves win in every political struggle, although society seems to be delivered over from the hands of one set of criminals into the hands of another set of criminals, as fast as the government is changed, and the march of civilization is a train of felonies, yet, general ends are somehow answered.

It is the most we can expect, more than we could hope for.

This Issue

March 7, 2024

Circuit Breakers

‘She Talk Her Mind’

Ready to Rumble

-

1

Henry Thoreau: A Life of the Mind (University of California Press, 1986); Emerson: The Mind on Fire (University of California Press, 1995); William James: In the Maelstrom of American Modernism (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2006). See also his First We Read, Then We Write: Emerson on the Creative Process (University of Iowa Press, 2009), and my review in these pages, December 3, 2009. ↩

-

2

In the biography, Richardson quotes this statement in a slightly different wording. ↩

-

3

In this connection we are inevitably reminded of another visitor to the Jardin des Plantes, and another experience of nature that helped to point the way to the accomplishment of a lifetime’s work, in this case in poetry. In the early years of the twentieth century the young Rainer Maria Rilke spent long hours in the Jardin des Plantes, studying the animals housed there. Among the results was “The Panther,” one of his greatest short poems. ↩

-

4

Although here he might have directed his shaft at the more culpable Saint Paul, hater of life and arch misogynist. As Nietzsche has it in The Antichrist, “In truth, there was only one Christian, and he died on the cross.” ↩

-

5

It is hardly necessary to observe that if this was true in Thoreau’s time, it is a paramount truth in ours. ↩