More from the Review

Subscribe to our Newsletter

Best of The New York Review, plus books, events, and other items of interest

Advertisement

More from the Review

Subscribe to our Newsletter

Best of The New York Review, plus books, events, and other items of interest

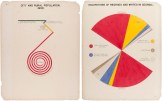

The Color Line

W.E.B. Du Bois’s exhibit at the 1900 Paris Exposition offered him a chance to present a “graphical narrative” of the dramatic gains made by Black Americans since the end of slavery.

W.E.B. Du Bois’s Data Portraits: Visualizing Black America: The Color Line at the Turn of the Twentieth Century

edited by Whitney Battle-Baptiste and Britt Rusert

Black Lives 1900: W.E.B. Du Bois at the Paris Exposition

edited by Julian Rothenstein, with an introduction by Jacqueline Francis and Stephen G. Hall

A History of Data Visualization and Graphic Communication

by Michael Friendly and Howard Wainer

August 19, 2021 issue

Rebellious History

How should historians construct a more complete and truthful version of the past?

Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Riotous Black Girls, Troublesome Women, and Queer Radicals

by Saidiya Hartman

October 22, 2020 issue

The Real Texas

People go to Texas seeking fortunes, hoping to find a place somewhere between what is real and what is myth; it is strange and disturbing that this hope resembles the feeling that brought Anglo settlers, along with the people they enslaved, into the region so long ago.

In a Narrow Grave: Essays on Texas

by Larry McMurtry, with an introduction by Diana Ossana

God Save Texas: A Journey into the Soul of the Lone Star State

by Lawrence Wright

The Injustice Never Leaves You: Anti-Mexican Violence in Texas

by Monica Muñoz Martinez

Big Wonderful Thing: A History of Texas

by Stephen Harrigan

America’s Lone Star Constitution: How Supreme Court Cases from Texas Shape the Nation

by Lucas A. Powe Jr.

October 24, 2019 issue

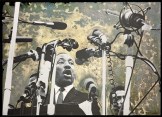

MLK: What We Lost

Figures like Martin Luther King, Harriet Tubman, and Rosa Parks have now become “safe” in ways they never were when they were operating at the height of their powers.

To the Promised Land: Martin Luther King and the Fight for Economic Justice

by Michael K. Honey

Redemption: Martin Luther King Jr.’s Last 31 Hours

by Joseph Rosenbloom

The Heavens Might Crack: The Death and Legacy of Martin Luther King Jr.

by Jason Sokol

The Seminarian: Martin Luther King Jr. Comes of Age

by Patrick Parr

To Shape a New World: Essays on the Political Philosophy of Martin Luther King, Jr.

edited by Tommie Shelby and Brandon M. Terry

November 8, 2018 issue

Female Trouble

‘What Happened’ by Hillary Rodham Clinton

What Happened

by Hillary Rodham Clinton

February 8, 2018 issue

Our Trouble with Sex: A Christian Story?

Geoffrey Stone’s ‘Sex and the Constitution: Sex, Religion, and Law from America’s Origins to the 21st Century’

Sex and the Constitution: Sex, Religion, and Law from America’s Origins to the Twenty-First Century

by Geoffrey R. Stone

August 17, 2017 issue

The Captive Aliens Who Remain Our Shame

On the origins of racial exclusion in the society that would become the United States of America.

The Common Cause: Creating Race and Nation in the American Revolution

by Robert Parkinson

January 19, 2017 issue

Free calendar offer!

Subscribe now for immediate access to the latest issue and to browse the rich archive. You’ll save 50% and receive a free David Levine 2025 calendar.

Subscribe now

Give the gift they’ll open all year.

Save 65% off the regular rate and over 75% off the cover price and receive a free 2025 calendar!