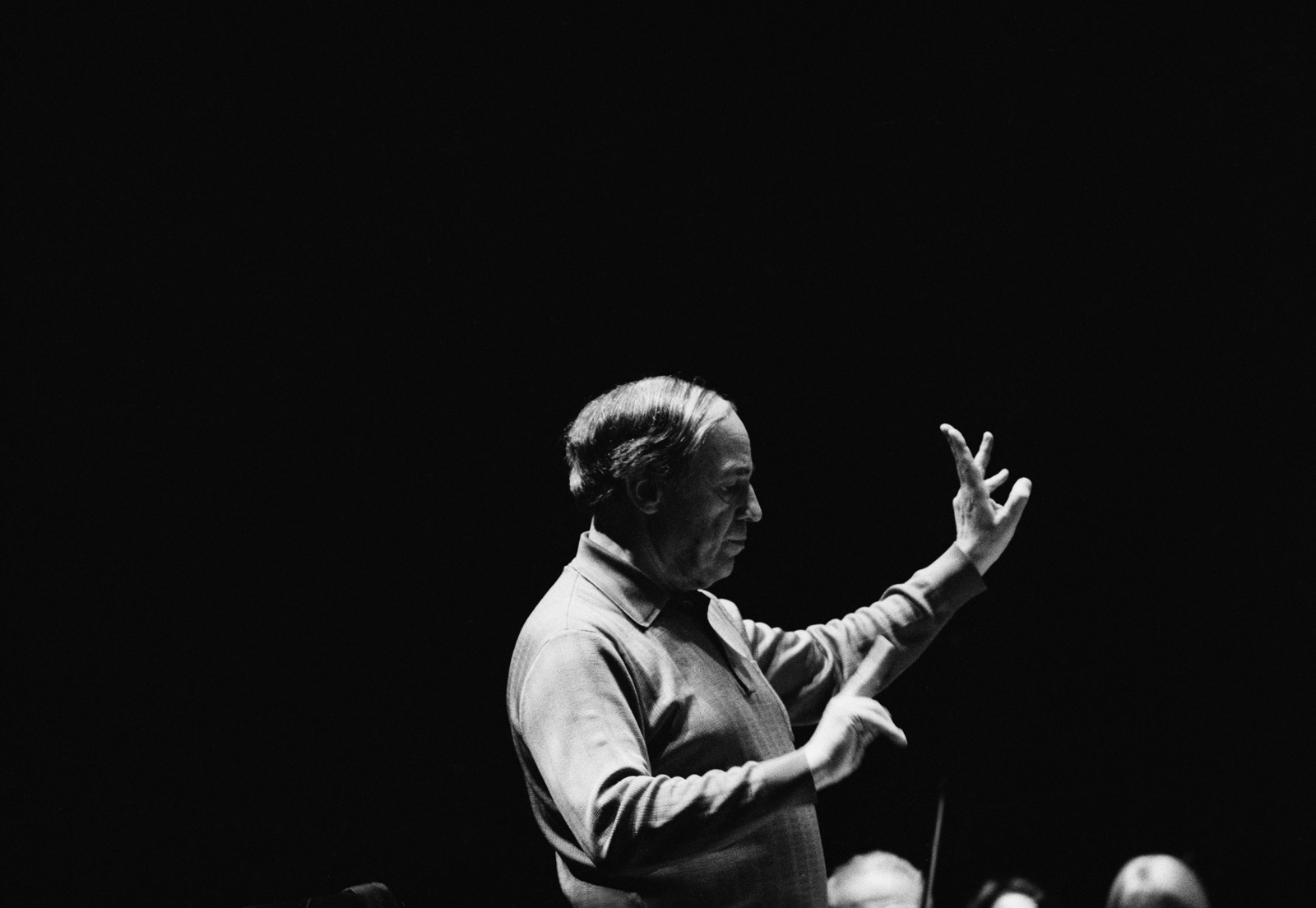

Pierre Boulez, the radical modernist composer who later in his career became one of the most sought-after conductors in the world, was famous for his polemics. “I suggested that it was not enough to add a moustache to the Mona Lisa,” he once said.

It should simply be destroyed. All I meant was just to urge the public to grow up and once for all to cut the umbilical cord attaching it to the past. The artists I admire—Beethoven, Wagner, Debussy, Berlioz—have not followed tradition but have been able to force tradition to follow them. We need to restore the spirit of irreverence in music.

As a young man, he dismissed composers ranging from Tchaikovsky to Brahms to Shostakovich to Olivier Messiaen, whose compositions were, respectively, “abominable,” “a bore,” “third-pressing Mahler,” and “brothel music.” Italian opera was “a delirium of bel canto”; the classical French musical ideals of clarity, balance, and grace were “Descartes and haute couture.”

This was not simply abuse for its own sake, but an attempt to underscore what Boulez felt was the urgent need for innovation in the postwar era. The musical forms of the twentieth century, he believed, had been creatively exhausted. His search for the new led Boulez to a brief experiment in the early Fifties with total serialism, which applied Schoenberg’s technique of serial ordering not just to pitch, but to rhythm, dynamics, tempo, timbre, and even the way in which notes were attacked. Though he soon distanced himself from the technique—later suggesting that excessive devotion to serialism was a form of “frenetic arithmetic masturbation”—for many this is the image of Boulez that has stuck: a bullying, icy modernist whose music was forbidding and academic, full of jagged asperity and rhythms that unfold in what Alex Ross aptly called “a rapid sequence of jabbing gestures, like the squigglings of a seismograph.”

Yet Boulez also wrote music that is in its way lush, colorful, and sensuous, reminiscent of Ravel and Debussy and as French, to the composer Nico Muhly, as butter swirling in a pan. To a listener encountering it for the first time it is still music that can be disorienting—as Boulez intended it. The critic and biographer Peter Heyworth, in his initial attempts to listen to Boulez’s music, wrote:

At the start, I could perceive little but a maddeningly incessant and seemingly shapeless plinking and plonking of percussion and plucked strings, for, like most ears at that time, mine were still trying to pick out themes and follow their evolution, and, of course, there were no conventional themes in this music.

Yet, Heyworth continued, “Once I ceased trying to impose irrelevant ways of thought upon it, its cool yet intense lyricism and the steely delicacy of the instrumental writing began to become apparent.”

These qualities are easy to hear in compositions like Le Marteau sans maître (1954), a setting of three poems by the Surrealist René Char, in which Boulez significantly relaxed the strictures of his earlier, total serialism. For many it is, along with The Rite of Spring and Pierrot Lunaire, a defining work of twentieth-century music. More sensuous still is Pli Selon Pli (1960), his musical portrait of Mallarme. Yet of all his compositions, the one that may give the most pleasure on first listening is one that must be heard in person in order to truly appreciate, and that—perhaps unsurprisingly—is hardly ever performed. That work is Répons, a late electronic composition for orchestra, six soloists, and an audio-acoustic system that was recently staged at the Park Avenue Armory by the Ensemble Intercontemporain.

Though Répons wasn’t composed until the early 1980s, the inspiration for the piece might be seen to date to May 1968, when Boulez left Paris and returned to Saint-Étienne, his childhood home in the south of France. The country was in the grips of les événements, the large-scale student protests that eventually brought all of France to a standstill. In the months prior, Boulez had been on the verge of introducing widespread changes meant to professionalize and modernize the hidebound Paris Opera, and there had been talk of making him its director. Instead, in the turmoil, his chief political supporter resigned, and, soon after, Boulez resigned as well.

In Saint Étienne, he gave a speech titled “Où En Est-On?” (Where Are We Now?) to a group of students. In it, Boulez surveyed the state of contemporary music and the way in which he believed it had reached a moment as decisive as the one architecture had reached fifty years earlier, as concrete began to replace brick and stone. Peter Heyworth summarized the speech in a profile of Boulez in The New Yorker:

Advertisement

An old world has lost momentum and direction; a new world has yet to be born.… The orchestra, which was evolved in the eighteenth century in response to certain harmonic innovations, is today obsolescent. Insofar as concert life has been reduced to interpreting a repertory that does not renew itself, it is dying. Both concert halls and opera houses are increasingly ill-suited to the needs of new music. Instruments are related to the requirements of the past. Electronics, once the hope of the future, have failed to evolve. Too many composers, having lost touch with the general musical public, have withdrawn into enclaves in which they thrive on mutual esteem and little else.

Boulez closed with a call for what Heyworth described as “a far-reaching collaboration of composers, performers, and scientists in a properly equipped research center, which might play a role similar to that played by the Bauhaus in the emergence of modern architecture.”

Boulez realized this goal in the late 1970s with the Institut de Recherche et Coordination Acoustique/Musique, known as IRCAM, the electronic music institute that he opened at the behest of French President Georges Pompidou. The initial goal behind the institute was not to replace instrumental with electronic music, but to work so that the two would mingle and, in Boulez’s words, “live together like cotton and rayon.” In its early years, IRCAM was criticized as a folly. It ate up as much as 70 percent of France’s state budget for the arts, and even as the personal computer revolution was underway, Boulez remained fiercely dedicated to the use of large, ludicrously expensive computers on the order of Milton Babbitt’s wall-sized RCA Mark II Synthesizer (even today, Répons is so infrequently played in part because of the prohibitive cost of the electronic systems it uses). Though IRCAM was not, ultimately, the kind of Bauhaus that Boulez had envisioned in his speech, by 1981 he had nevertheless used the institute’s resources to produce Répons, a piece that finally seemed to answer the persistent question of what IRCAM had been doing with so much of the state’s money.

The piece, which Boulez revisited several times, ultimately extending it to a length of about forty-five minutes, is written for three separate groups: an orchestra, six soloists, and what the score calls an electro-acoustic system of computers and loudspeakers. The orchestra sits at the center, surrounded by the audience, which is in turn surrounded by six soloists playing percussion instruments—the cimbalom (a kind of Hunagarian zither); harp; vibraphone; xylophone doubled with glockenspiel; and two pianos, one of which is doubled with an electric organ. Each of these solo instruments is hooked up to the electro-acoustic system, which analyzes, transforms, and spatially rearranges their sounds, dispersing them through a set of six loudspeakers.

It opens with the orchestra—spotlit at the Armory in a wonderful staging by Pierre Audi and Urs Schönebaum—playing unaccompanied. The ensemble unleashes lurching and spasmodic phrases that give way to frantic woodwind runs, growling brass, and ostinatos—insistently repeated phrases—reminiscent of Steve Reich’s Music for 18 Musicians.

At the end of this section, the piece changes radically. The six soloists enter together, each playing an arpeggiated chord—in which the constituent notes are sounded in sequence from the lowest pitch to the highest. It is a brilliant, theatrical explosion of sound that Ara Guzelimian, the dean and provost of Juilliard, compared to the shift from black and white to color in The Wizard of Oz.

Here, the complex audio system first comes into play. The soloists’ initial chords continue to resonate for about eight seconds, and as they do are circulated, slightly altered, throughout the six loudspeakers surrounding the audience, bouncing quickly from speaker to speaker at first, then slowing at different rates as their volume diminishes. As the initial notes finally fade, hanging almost frozen in the air, the soloists enter again one by one, each playing another arpeggio, treated and echoed, so that each successive soloist seems to be answering the echo of the last.

Today, these effects do not perhaps strike us as technically impressive, but what is so remarkable about the piece is how gently and organically it integrates the computers into the whole of the composition. The ensemble’s conductor, Matthias Pintscher, described how even the subtlest changes could affect a performance of the piece:

If the vibraphone or second pianist plays one chord a little later, or a little softer, or highlights the top notes in the chord a little more—that has a consequence [in] how someone else responds to that, how I respond. Do I just hold my breath a little longer to introduce a new color, or am I just going right in with a new color?

Boulez compared the structure of the composition to the spiral ramp at the Guggenheim. “The form is permanent,” he said, “but as you go up you see the whole thing from a series of different perspectives.” At the Armory, the piece was performed twice, with audience members changing seats for the second performance. The shift in perspective emphasized the degree to which no two performances of Répons are the same, bringing to light seemingly new instances of call and response between the electronically treated soloists and the acoustic orchestra, among the soloists themselves, and even a difference in the way that the sounds, captured and dispersed by the electronics, traveled through the space itself.

Advertisement

Sitting surrounded by the soloists as their sound raced around the speakers, offset by the fixed sound of the orchestra, felt at times like looking out from the center of the solar system, watching the planets orbit. The call and response shifted throughout the piece, at some times as if the soloists were shooting phrases into the orchestra, only to have it shatter and refract them. At another moment, the orchestra played a vicious ostinato, and the soloists responded as if they had been struck by its force, reverberating almost like wind chimes.

When Répons was first performed to much anticipation in New York in 1983, The Times’s critic, Donal Henahan, found it a disappointment.

At odd moments it was superficially stimulating in the way a cold shower can be, but as music it added up to little more than a series of unconnected tone clusters, arpeggios and pedal notes. Most surprisingly, in view of Mr. Boulez’s international prestige as one of music’s foremost intellectuals, “Repons” asked for no special concentration. However rigorous its plan and structure may be—and no one doubts Mr. Boulez’s ability to construct a score of great logical beauty—its effect was oddly random. “Repons” was a bath of sound, too long drawn out to be really invigorating.

The recent performance at the Armory seemed—to me, at least—considerably more exhilarating. One of the things that seemed so remarkable about Répons was precisely that randomness: that two back-to-back performances of such a rigorously and logically composed work—carefully plotted from beginning to end—could, in the hands of an elite orchestra founded by Boulez himself, sound at times like two different works. Far from stifling the human element, the use of electronics in Répons helps bring it to life, giving the piece an almost living, breathing mutability. Hearing it live made it clear why Boulez once said that listening to a recording of the piece was the equivalent of looking at a photo of one of Calder’s mobiles.

Répons may not have provided the kind of roadmap for the evolution of electronics in music that Boulez once hinted at it, but it makes an urgent case for the importance of live performance. More than that, Répons gives easy access to the kind of beauty to be found in the work of a composer whom Charles Rosen once called “the master of iridescent sonorities.”

Pierre Boulez’s Répons, conducted by Matthias Pintscher, was performed by the Ensemble Intercontemporain at the Park Avenue Armory October 6–7.