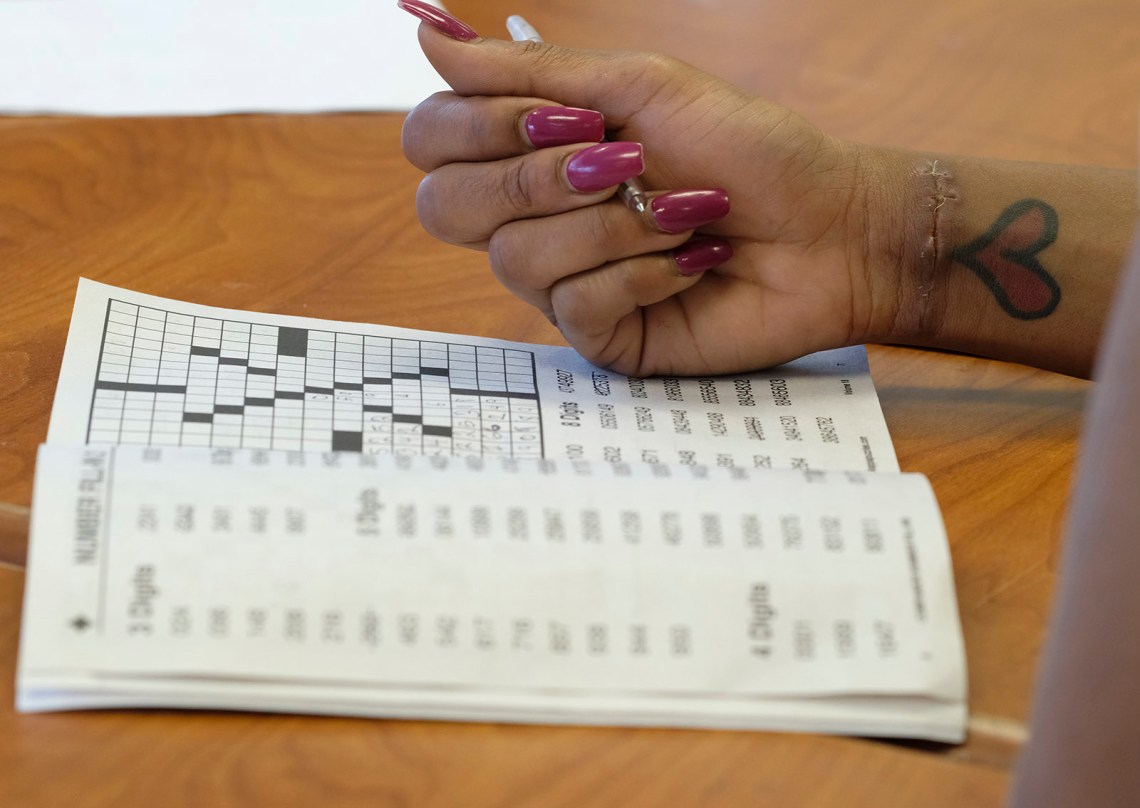

I listened to Aleeyah, a new psych patient at Kings County Hospital in Brooklyn, speak, hanging on her every word and gesture. She was about twenty, dressed in a festive multicolored sweatshirt that spelled Brooklyn with arty graphics and that revealed some of her wrist and neck tattoos, which she said she designs and does herself. Her affect was a little flat but not that of an acutely depressed person; in fact, she seemed rather upbeat and had a glow about her.

She played to me on her phone a rap track that she’d recently recorded in which she rhymed and created the beats. It began: “I love the life I’m living / Pursuing every mission.” Then she casually mentioned that she had tried to hang herself the previous month with an extension cord, an act she said had never occurred to her before that moment. The drama of life had got too much: a bad breakup, two short stays in jail, and a sister with cancer. She would have been dead if her sister hadn’t walked into her room at the right time, cut the cord, embraced her, in tears, and brought her to the hospital.

Our conversation about her mental state and what had happened was not unusual for me given that I’m a therapist by profession. But I am not Aleeyah’s shrink. I am a photographer, who had just met her on the third floor of the Kings County R building, where I have been meeting many other young people with similar stories over the past two years. Since 2017, I have been an artist-in-residence at the Kings County Hospital, working on a photography project in its six-week partial hospitalization program for people transitioning from inpatient stays, spending about a day a week there getting to know the young adults in the program who come from communities nearby and from all over NYC, with a range of diagnoses and having suffered a variety of traumas.

The psychiatry department of Kings County Hospital in East Flatbush serves one of the poorest, most at-risk, and most diverse populations in a borough that has otherwise become a byword for gentrification. Kings County has a notorious past that culminated in the 2008 death of Esmin Green, a Jamaican woman who died from neglect after being placed on the psych ER’s waiting room floor for twenty-four hours. Following a Department of Justice Civil Rights Division investigation of her death that was concluded in 2010, Kings County has undergone a remarkable renaissance in the quality of patient care and transparent governance.

In the course of the artist residency, I have met many inspiring patients of obvious charisma and talent, albeit with distressing backstories. This fault line between the “normalcy” of young adulthood and the psychopathologies that landed them in the hospital is palpable. I met Jaice, who at twenty made a philosophical case to me justifying suicide based on a lifetime’s experience of abuse, her mother’s involvement in a cult in Seoul (and eventual suicide), and the difficulty of being an immigrant gay non-binary teen (her is her preferred pronoun). But in virtually the same breath, Jaice told me of her academic goals, and her passions for helping the Rohingya in Myanmar and caring for the environment. Jaice can easily find herself engulfed by despair, but when I texted her a couple of photos that we took together on a Brooklyn rooftop last month, she wrote back: “I feel so amazing and powerful in looking at myself in those photos.”

I met Talitha, who came from a low-income Puerto Rican family in Brooklyn and won a scholarship to a top New England college to study economics. She suffered from sporadic dissociative episodes during which she would disappear for days in remote rural areas; by the time she was found, on each occasion, she would have attempted suicide by cutting. And I met Mya, who had straight As through high school and trophies all over her bedroom, but her manic episodes kept getting worse and landing her back as an inpatient.

From the outset, I wanted to enter the hospital without a strict agenda and be open to whatever and whoever I would find. I have tried to avoid the ethical pitfalls of making visual art about mentally ill populations, pitfalls that even the greatest work doesn’t always manage to avoid—witness Frederick Wiseman’s brilliant but problematic 1967 film about a prison psychiatric facility in Massachusetts, Titicut Follies, which foregrounds questions of First Amendment expression and social reform and the privacy rights of psych patients. Just as psychotherapeutic practice has evolved from the model of an authoritative doctor’s treating a patient to a more relational one in which meaning and interactions are seen as jointly constructed or intersubjective, my hope is that these images are produced collaboratively and reflect an authentic two-way conversation that goes beyond the reductive labeling and stigma of diagnosis.

Advertisement

I hope, too, that the duality of my career—as psychotherapist and photographer-artist—could give these patients a platform to present both their inner and outer selves. I’ve grown more comfortable than I anticipated in sometimes bringing an aesthetic from my previous work of shooting artists like Beck, Mary J. Blige, and Lena Dunham—a more glossy music journalistic sensibility—to what may seem painfully dark subject matter. To me, that collision of representational status—between the faces everyone clamors to see and those that few wish to, or do, see; between the impoverished and the inconceivably wealthy; between the glamorized and the denied—has value. The suicidal, the psychotic, those on the edge, they are as worthy of the visual vocabulary one might use to depict the celebrities of creative culture.

As for my subjects, I have found that while they sometimes choose to allow me into their lives to capture more vérité images, they also want to make beautiful pictures of themselves, even in the most drably institutional of settings and at a low point in their lives. In partnership, we’ve combined pictures and words from their writing and interviews that give them a mode of self-expression, telling a story while remaining documentary. Many have mentioned a desire to share their stories in hope of helping other young people who don’t necessarily know what help is available or that others experience similar mental states. We have shot in the hospital itself or ventured out to places that hold meaning for them. Jaice wanted to go to Greenwood Cemetery, “a place where I wanted to lie down to rest and die before I was hospitalized… lying down in the green, drinking bubble tea before I die… to me, when I was outside looking in, it was perfect.”

Some of my subjects I have known for over a year; some for only an hour. One of these patients, Nathaniel, and I published a piece to which he contributed a poem dedicated to his mother, whose rejection of him when he transitioned in his teens led to his running away from home. We included photographs taken of him and his family in their home and near the shelter he had lived in, a Covenant House facility. Another, Theo, a poet who said she was either walking into the hospital or into traffic before I met her, has worked with me as a participant–observer to use images and her poetry to rethink the whole narrative of her life that led up to her hospitalization. Recently, she wrote to me:

Our conversations made me feel less institutionalized. Inside our discussions of art and how art can help the brain repair, I felt safe from slant of medical imagination… I think this is why my favorite photograph from the series is the first. Trying to remember how to smile in too-big overalls, I am indeed more than my diagnosis: I am tight-faced and unsure and committed to beginning again as many times as it takes. With this collaboration, I am hoping to build a kinder language to shape the stories we tell about ourselves for anybody who has ever confronted brain or body or heart as passenger.

I have focused on twenty-somethings out of an interest in youth culture, just as I work with adolescents in clinical settings on a daily basis (but not with a camera), and from my background as a photographer touring with rock bands. But it is really because I’m enlivened by the undimmed sense of youthful possibility lodged within the acute suffering found in the unit. My aspiration is that these images will live as a document of a time and place, both for these precarious individual lives and, more broadly, for those on the margins who find themselves entangled in our flawed mental health system.

Advertisement

While for some their stays at Kings County may pave the way back to stability, many have daunting prognoses and face a healthcare system that all but guarantees future trips back to the psych ER. Insurance companies or Medicaid pay for only six weeks of care at a time, and value medication and biological explanations of illness above talk therapy and an understanding of underlying causes. These young patients rarely get sufficient outpatient treatment covered after they are discharged and often have little social support to help them stick to treatment. For those who have felt able to participate in this project, my hope is that the telling of their stories and the fact that someone cares enough to listen can be therapeutic, even if it is not itself therapy.

This essay and the author’s photography are supported by the Economic Hardship Reporting Project. The author’s artist residency at Kings County Psychiatric Center is sponsored by Residency Unlimited.

An earlier version of this piece misstated the first name of the director of Titicut Follies; it is Frederick Wiseman, not Robert. The essay has been updated.