All that is overwhelming about public space in São Paulo, Brazil’s business capital—the noise, the teeming crowds, the endless stream of cars and buses—is exacerbated on the Avenida Paulista, a stretch of concrete lined end to end with shiny glass office towers. The tropical noonday sun bounces off in splinters from the towers, the evening rush-hour turns the avenue’s wide sidewalks into a mob scene and, in short, everything about this urban landscape seems to confirm one’s suspicion that present-day capitalism shrivels or denatures everything it touches.

It is with a sense of prayerful relief, then, that a traveler might find herself in a quiet exhibition space several floors above the Paulista, wandering through a visual forest of images of the upper Amazon basin’s first peoples—a retrospective of work by the Swiss-born emigré photographer Claudia Andujar, titled “A luta Yanomami” (The Yanomami Struggle), mounted at the Moreira Salles cultural institute. Andujar began documenting the Yanomami in 1971. Her black-and-white photographs—suspended from the ceiling at eye level—form a composite portrait of the Yanomami people, once fierce in their independence and isolation but currently fighting for survival. In this white-walled enclosure one is free to contemplate the infinitely strange and elaborate lives of human beings who, in the first of two large rooms, are shown living on what we could consider absolutely nothing.

No clothes, for one thing. Men tie their foreskins with a bit of string and then knot it to a second string around the waist, so that the penis points jauntily upwards at all times. Women don a necklace of tiny beads and the smallest of aprons. A little face paint, a palm reed through your septum, a feather or two, and you’re ready for the day.

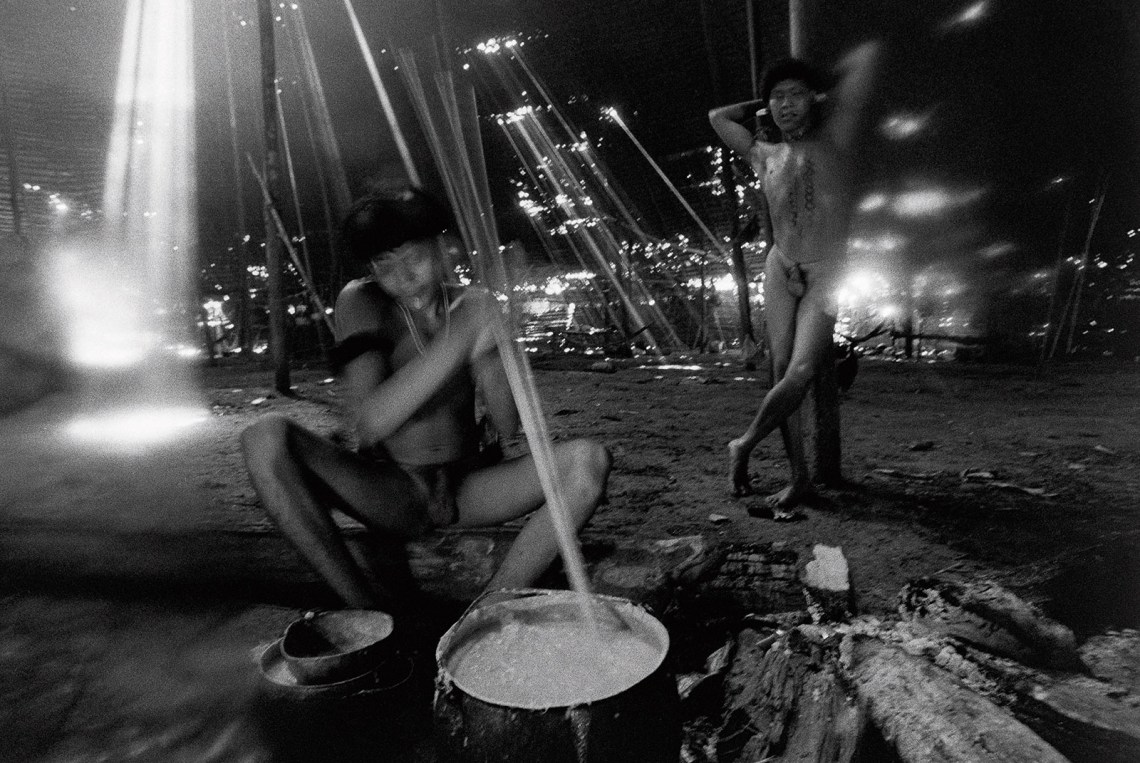

The Yanomami communities in these images live out their lives mostly inside an enormous shabono (sometimes also called a maloca), a thatched, circular enclosure that is at the same time home to an entire clan, and a symbolic representation of the universe. Families live in assigned sections of the shabono with a pot or two for cooking and one mesh hammock per person. There are a few extras; reed arrows and hollow tubes for blowing hallucinogenic snuff into one another’s nostrils (used by men only); pots for preparing poison for the arrow tips, hallucinogens and medicines of various sorts; stools for the elders.

In the early photographs, the various trinkets and goods brought in by missionaries and anthropologists—machetes, mirrors, radios, shorts—are not in evidence. The community’s daily routine portrayed here involves a small amount of hunting by the men, who are happy when they can bring a large monkey or a peccary home for dinner. The women tend to the plantain and squash crops beyond the shabono, and cook.

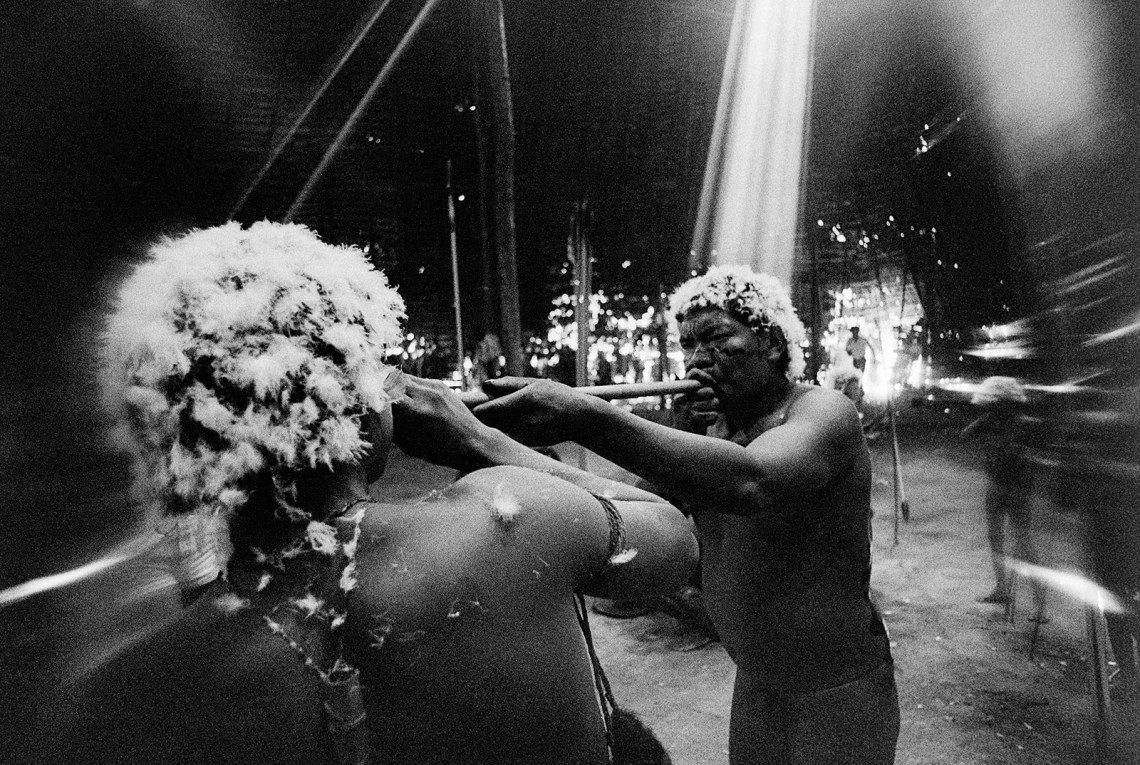

Andujar’s images of this group culture are attempts to translate the intense spiritual life of the community into visual language, and they are extremely beautiful. Young men look like angels, their hair adorned for a feast day with snow-white down plucked, if I am reading the splendid catalog correctly, from the chest of vultures. On a glittering river, the brown skin of young girls resembles velvet. At night, the many bonfires in a shabono are photographed from the outside, so that the light glints and winks through flimsy reed walls, and the whole thing looks like a new galaxy surrounded by other stars.

Through this haze of enchantment, though, an uncomfortable question is hard to avoid: Are the photographs revealing a magical and now lost world, an alternate turn in the long road of evolution that we failed to take, to our sorrow, or do they hide a nastier, brutish truth? It depends on your sources. The Yanomami—an anthropologists’ designation for the various tribes and clans that live in a designated homeland along the border between northern Brazil and southern Venezuela—number some 25,000 people today. They occupy 130,000 square miles of the Amazon jungle, part of which was ceded to the groups living in Venezuela in 1991, and the rest by Brazil in 1992.

Famously, an anthropologist named Napoleon Chagnon wrote a book in 1968 in which he described the various Yanomami tribes as living in a state of “chronic warfare.” According to Chagnon, the Yanomami world was a machismo-made hell: inter-tribal conflict broke out most frequently over women, who were scarce thanks to the custom of infanticide of girl babies at birth. Thus, according to Chagnon, the rape and abduction of women had evolved into the primary cause of inter-communal fighting: men who killed the most enemies had access to the greatest number of women, and consequently produced the most offspring, meaning that their genes were distributed most widely. The tribes, Chagnon wrote, had an irritating habit of demanding gifts in an unsubtle and insistent way. The “burly, naked, filthy, hideous men” stank, and were made particularly unsightly due to the green mucus that trailed from their noses following a session with the snuff blowgun.

Advertisement

How true is this picture? Well, some of it, yes, and some of it, no. Never mind about the snot; Chagnon, who wrote in take-no-prisoners style, was attempting an anti-Margaret Mead, whose “Coming of Age in Samoa” had been criticized as romanticizing the natives. Her upstart challenger aimed for a just-the-facts approach, but a certain bias crept in. To begin with, Amazon people are small, averaging only about five feet—so hardly “burly.” Further, anthropologists who had been living with the tribes for far longer than Chagnon reported that war between them was actually a rare occurrence. A contre-Chagnon was published by another anthropologist, R. Brian Ferguson, in 1995. This was followed by a ferocious attack from the pro-indigenous peoples activist Patrick Tierney, who spent years investigating Chagnon’s passage through the jungle and wrote a book about it in 2000.

One of Tierney’s initial accusations—that a measles vaccination campaign co-sponsored by Chagnon might have contributed to a measles epidemic that devastated the Amazonian communities—has been discredited, but it is hard to argue with his claim that Chagnon’s research methods altered the communities he studied in highly damaging ways. Tierney denounced, for example, Chagnon’s reckless practice of distributing machetes and other valuable items as bribes so that tribal members would surrender taboo information to him.

The bitter argument over Tierney’s book and Chagnon’s work was actually about a number of things, including the sanctity of academic research and the concept of the primitive, but one question not addressed was why women like Margaret Mead saw things so differently from their male colleagues. Why do Claudia Andujar’s photographs show a world in which fathers are gentle with their children, everyone bathes with pleasure in pools and rivers, and feast days are explosions of joy for men and women alike? Why did she write, through the decades, of feeling calm and complete—at home—when she was among the Yanomami? Perhaps she, and Mead, were sentimental. Perhaps she approached her subjects differently, and saw things others did not. She may have felt, also, that it was better not to publish anything negative about a fragile people so brutally under attack.

*

Andujar was born Claudine Haas in Neuchâtel in 1931 into a strict family; her father, a prosperous factory owner, was Jewish, her mother was Protestant. Although her father, and much of his side of the family, died in Dachau and Auschwitz, Claudine was able to emigrate and went to live in New York with an uncle. While Claudine, now Claudia, met, married, and divorced a young Spanish immigrant, Julio Andujar, graduated from Hunter College, and took up painting, her adventurous mother went to live in Brazil with her Romanian fiancé. In 1955, Claudia went to visit her there, and ended up staying forever.

A year into her new life in São Paulo, Andujar had become a professional photographer, taking pictures of the Karajá peoples in north-central Brazil. By the time she traveled to a Catholic mission in the heart of Yanomami territory, she had been crisscrossing Brazil and taking photographs of indigenous communities for Brazilian publications for nearly fifteen years.

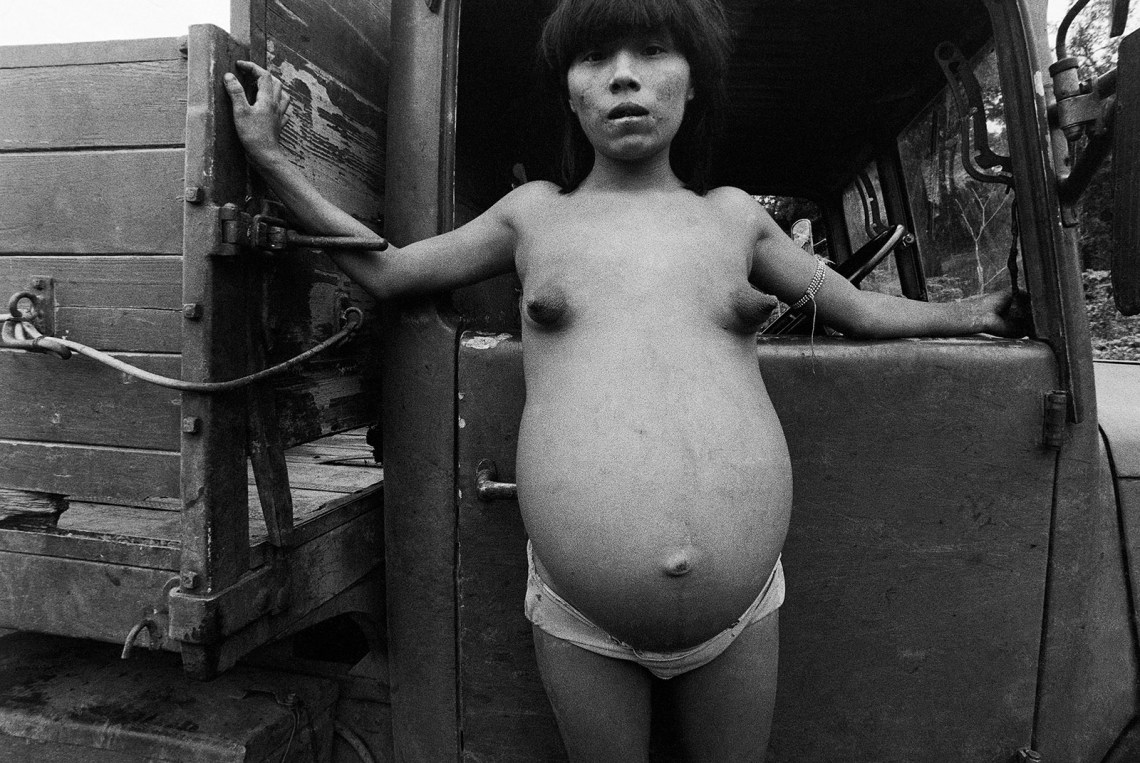

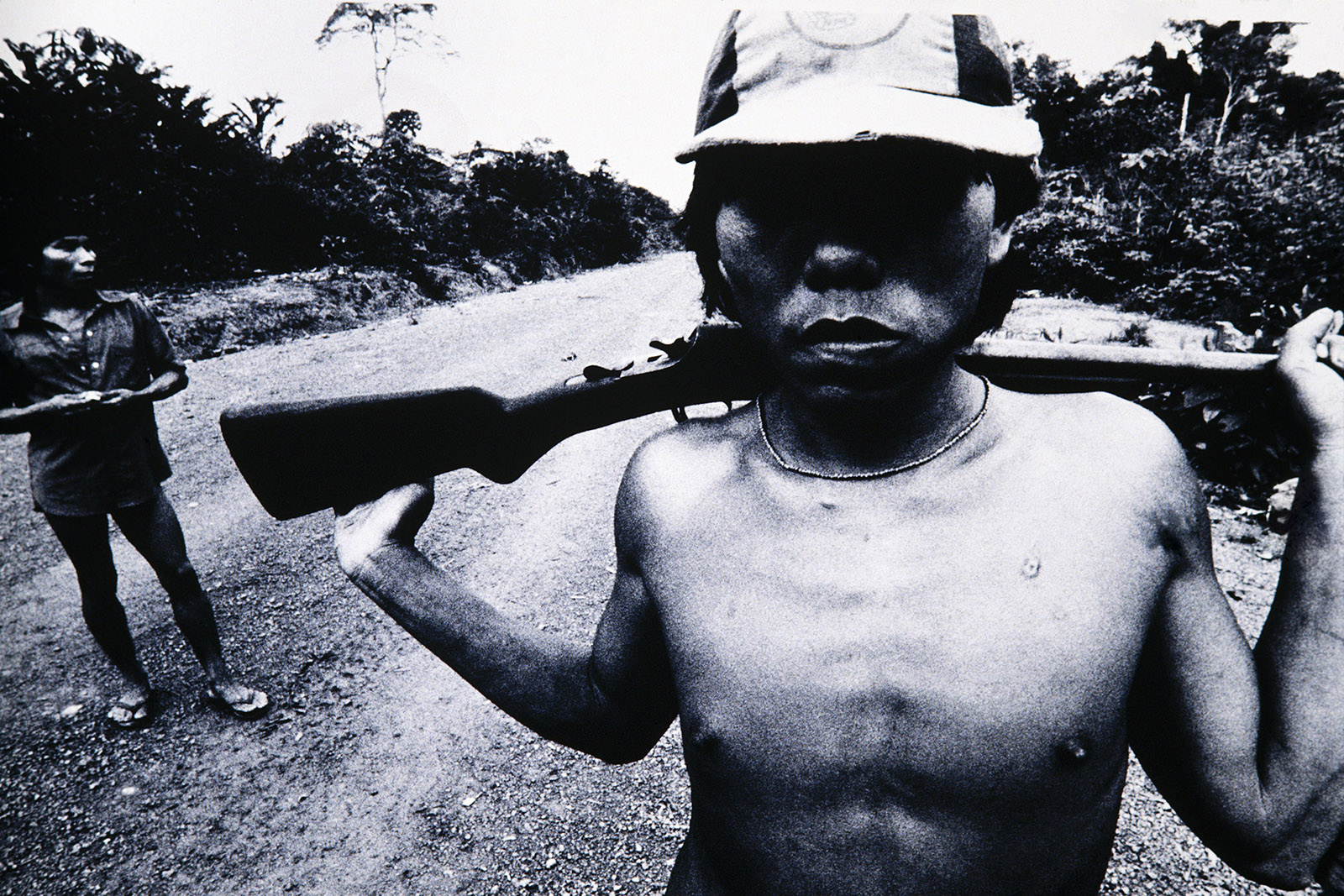

The people who appear in the second section of Andujar’s retrospective, a floor below the first, are wearing clothes: filthy T-shirts or ripped shorts, rarely both. Flip-flops, sunglasses, sometimes a bra for the women, who are more often exposed in ways that don’t seem right.

The photographer arrived in Yanomami territory at the precise moment when Brazil’s military dictatorship, true to its motto of “Ordem e progresso” (order and progress) was driving a highway straight through the Amazon, in the hopes of making the jungle an agricultural Eden for landless immigrants from the rest of Brazil. That road remains unfinished forty-five years later, and there is no Eden. Instead, the opening of the Amazon brought lumberjacks, gold miners, bounty hunters, construction equipment operators, tavernkeepers, and landrobbers, all of them vectors carrying diseases that would course through the Yanomami territory and leave it rich with corpses, suspended, according to the peoples’ religious custom, in rope cages in the forest canopy.

Advertisement

There is only one image of an “air burial” in the exhibit, and one would never know what it is simply from looking at it. Nevertheless, it is right that this second section of the exhibit is staged a stairway down from the first, because it describes a descent into the hell of modernization that has awaited all tribal peoples, from New Zealand to the Amazon. The tour presented here offers a familiarly bleak perspective, even if Andujar chose long ago to leave out the worst images of disease and death.

The cultural dislocation and physical suffering Andujar witnessed shocked her so, and appear to have put her so in mind of the genocide in Europe, that by the 1980s photography became a secondary concern for her. Together with a group of doctors, she started a health services and vaccination campaign in Yanomami lands. With the anthropologist Bruce Albert, Carlo Zacquini, a Catholic missionary and friend, and the Yanomami shaman, translator, and indigenous rights crusader Davi Kopenawa, Andujar campaigned relentlessly for a designated homeland for the people she had come to love. It is thanks to her and her fellow activists that the Yanomami Indigenous Territory exists today. By protecting the Yanomami, it has also protected, thus far, the countless creatures and remarkable ecology of that small corner of the Amazon.

Now eighty-seven, Andujar is suffering from the effects of a rugged life. Malaria took its toll on her, but she also now suffers from arthritis and other ills. Even so, by means of a chartered flight, she managed to visit the Yanomami territories as recently as 2017, traveling two hours down a jungle path in a wheelchair pushed by her old friend Zacquini. She is unquestionably a woman of heroic stripe. Yet Chagnon was not wholly wrong in his observations about the role of violence in Yanomami culture, so one wonders whether Andujar failed to see, or decided to give no account of, the situation of the women, who, according to plentiful testimony, were indeed often subject to culturally approved rape, abduction, and abuse. Perhaps she took the ill-treatment of women for granted, as most people once did. In any case, one gleans from a book co-written by Albert and Kopenawa that the source of violence among the Yanomami was most often generations-long feuds, which could start with some incident of disrespect to an elder or an ancestor, or calling someone by their forbidden name.

*

In many respects, the old debates about identity and primitivism, once fought with so much passion, have run out of time, along with most of the tribal peoples that gave rise to such controversies. Even among the most delusionary romantics, it has long been understood that aboriginal culture will inevitably vanish. The question has always been how traumatic change will come to isolated or uncontacted tribes, and how much control these peoples will have over their transition to modern capitalist society—to what degree they will be able to decide what they want to retain of their culture and how to incorporate the new.

It is for this agency that Davi Kopenawa, Claudia Andujar, and Bruce Albert have fought for over long decades. But Brazil’s reactionary new president, Jair Bolsonaro, has brushed aside all such discussions. The areas of wilderness reserved for native tribes have been one of Brazil’s significant achievements, but these territories face constant pressure from an assortment of profiteers of all kinds, including agribusiness and big oil. “There is no indigenous territory where there aren’t minerals,” he said in an interview last year, campaigning on a promise of no new land for Indians. “Gold, tin and magnesium are in these lands, especially in the Amazon, the richest area in the world. I’m not getting into this nonsense of defending land for Indians.” On taking power, he delivered the responsibility for indigenous affairs to the Agriculture Ministry. Since his election, countless small budget cuts have destabilized the Yanomami’s subsistence economy.

Of course, the Yanomami are not the only ones under threat from the new regime: we all are. The Amazon currently loses nearly 3,000 square miles of jungle forest every year. It is terrifying to contemplate the impact that Bolsonaro’s assault on the area will have on climate change over the next four years of his presidential term.

“In a very real sense, the damage Bolsonaro will do to the environment, he has already done,” a Brazilian friend told me recently. Beyond the legislation turning over the Amazon and its indigenous communities to the Agriculture ministry, beyond the spending cuts and hostile decrees, beyond whatever legal predations are to follow, there is a new sense that any landowner or industrialist who feels like shooting an Indian or two, or clearing a few thousand acres for cattle-ranching, may do so with impunity. Policing the Amazon demands enormous sums of money and unwavering political commitment. Under Bolsonaro, it’s as though all the security cameras have been turned off.

A struggle for survival that has lasted half a millennium may be about to end: some of the last people on earth who look at the world and see a wondrously different reality from the one we perceive are all but defenseless under this new president. And it could be that soon all that will remain of their presence on this earth will be Claudia Andujar’s glorious photographs.

“Claudia Andujar: A luta Yanomami” (The Yanomami Struggle) was at the Instituto Moreira Salles, São Paulo (IMS Paulista), from December 2018 through April 2019, and will show at the IMS Rio, Rio de Janeiro, from July 20 to November 7. The exhibit will tour to the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, Paris, running from December 13, 2019, through May 24, 2020.