Everything in Palermo is slow except the traffic, which is as confusing as a video game and just as fast. But otherwise things pour as slowly as honey from a spoon. My bag was lost for twenty-four hours until a high official of the arts festival I was attending took the matter in hand; then it was found instantly. It had been at the airport all along. I won a nice little literary prize, the Premio Mondello, but I received it only after enduring a two-hour press conference in the morning and a three-hour ceremony in the afternoon, complete with local violinists sawing their way through a Baroque concerto in the beautiful convent cloisters of Palermo’s Galleria D’Arte Moderno. At one point, ten high school students got up to vote for another prize; each delivered a long-winded discorso, a sort of high-tone book report and a preparation for a lifetime of prolixity. That evening there was a banquet for thirty at which every other Sicilian man seemed to be a prince. They even address one another as “Principe,” which my Florentine date, Beatrice von Rezzori, told me was very “Southern.”

The next day yet another prince drove us to a strange hillside town, Salemi, which was almost entirely destroyed by the 1968 earthquake. Because things move slowly here, there are still bits of broken wall lying where they fell in the street. The cathedral has only one wall and a few columns still standing, though the nearby Piazza della Dittatura (where Garibaldi declared himself “dictator” of Italy) has been perfectly restored. One couldn’t say as much of the castle where Garibaldi for the first time flew the flag of Italy in 1860. The one place that was functioning perfectly was the new Museum of the Mafia where visitors stumble around in the dark before entering one booth after another, shutting the door and submitting to documentaries on how the Mafia has destroyed Sicily’s hospitals, how it replaced the beautiful old buildings of Palermo bombed out (by Americans) in World War II with ugly cement “projects.” How the Mafia is in cahoots with the local Catholic hierarchy. How various Mafia families are involved in perpetual vendettas from one generation to the next. The walls of the museum corridors are covered with hundreds of newspaper pages detailing Mafia murders back to the mid-nineteenth century; the sound track is of a typewriter clacking away.

A patron of the arts invited us to lunch at her country villa where she served wonderful little pasta rings (a local product) in a tomato and eggplant sauce and then slices of roast beef with potatoes, and finally six or seven different kinds of sherbet and ice cream, one lighter and more delicate than the next. Just when it seemed time for a siesta we were hurried off to a museum of bread! Yes, at Christmas time local peasant women fashion whole complicated scenes of a religious nature out of beautifully incised and toasted bread, all on display at this museum. Another man we met told us that he has a museum where living people stand about dressed as peasants of the nineteenth century practicing handicrafts.

Finally we were accompanied to the town of Gibellina, which was so badly destroyed in the 1968 earthquake that it was abandoned and paved over by the Italian artist Alberto Burri, who created a gigantic sculpture of flattened gray cement, on which some of the main streets are represented by deep incisions. It all looks like a giant launching pad stomped into a cow patty by a particularly violent space launch. Here we heard a very serious French cellist play a Kodály sonata. Then three other musicians from Paris performed an uncompromising string trio by Shostakovich. Finally we heard a violin and piano piece by Messaien, an homage to a bird or God or maybe both.

In the midst of the concert Vittorio Sgarbi, the mayor of Salemi—a television art critic, university professor (convicted of absenteeism), and newly appointed culture czar in Venice—arrived accompanied by police, read a poem or two by Juan Ramon Jimenez and chattered his way through the Shostakovich to his assistants when he wasn’t jabbering on the phone. He introduced a black call girl as “my official fiancée” to the tired smirks of his inner circle. When my date Beatrice said she had to leave by taxi to catch a plane for Florence, Vittorio told her she could be accompanied by his police escort and in that way skip the traffic lights and airport security. A long day came to an end at a nearby museum in an ancient granary; between the granary and the former farmhouse was a huge mountain of salt in which black statues of horses were foundering and sliding.

Advertisement

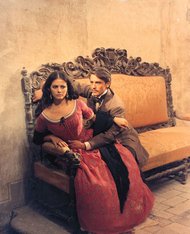

Alain Delon as Tancredi, the nephew of Prince Don Fabrizio, and Claudia Cardinale as Angelica, his nouveau riche fiancée, in The Leopard

The next day another prince, the ever charming and causally elegant Gioacchino Lanza Tomasi, who used to be the head of the Italian Cultural Institute at New York University, invited me to see Lampedusa’s library. Gioacchino met Giuseppe Tomasi, 11th Prince of Lampedusa, when he was a teenager; eventually the old childless prince adopted him. The palace looks out on a terrace covered with flowers and shaded by palms that faces the port of Palermo. Inside there are vast reception rooms, lit by Venetian chandeliers; one room contains the astronomical library of the nineteenth century ancestor who was the model for The Leopard, Lampedusa’s classic novel, published in 1958, about the decline of the Sicilian aristocracy in the late nineteenth century. In another room are the books in several languages (mainly Italian, French and English) that Lampedusa read over and over again. “He didn’t have many books,” Gioacchino says. “Just six thousand, but he knew them well. A bit like Montaigne.”

Lampedusa was married to a Baltic baroness, Licy, who had her own castle, Stomersee, in Riga. The prince and the princess were seldom together in the 1930s, so they exchanged hundreds of letters, which Gioacchino is now slowly preparing for publication. They, too, are written in Italian, French and German and talk extensively about their real and mostly imaginary ills and their beloved dogs. The German and then the Russian invasions of Latvia forced her to move to Rome and then to Sicily, where she practiced psychoanalysis on the local gentry. She kept completely different hours from her husband, who was an early riser. Licy got up around eleven, then prepared herself for a long day of treating her patients.

At night she and the prince might go to the movies, or listen to Wagner records, or eat one of her strange meals. She missed her beloved herrings in cream so much that she soaked local dried herrings in milk for days on end until they started bubbling and kept her in a constant state of diarrhea. The prince fled to his favorite cafes where he could eat a decent meal and meet his young cultured friends and work, during the last three years of his life, on The Leopard. To the young men he gave talks on literature that were later published; he also published stories and books about Stendhal and French Renaissance literature. He had finally escaped the laziness of the South.

Unfortunately he did not live to see the book published, the sole important fruit of a lifetime of reading and talking. His palazzo is full of reminders of the book—a telescope on the terrace and paintings of his ancestors everywhere, including a group of family saints! Yes, several members of his family were saints or at least “blesseds,” including one unhealthy looking pious lady named Maria Crocifissa. Yet another reminder of the book is Gioacchino himself, who served as the model for the looks and the désinvolture of the dashing young hero Tancredi.