Several remarkable things have happened here in Italy in the past week.

One: Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi, that self-styled man for all seasons—tycoon, soccer team owner, politician, crooner, swain—the perennial fixer who not too long ago said, in Milanese dialect, ghe pensi mi, “I’ll take care of it”—“il premier,” il Cavaliere (that is, Sir Silvio), has apparently been driven by the present political situation to say, “I don’t know what to do.” And he doesn’t, though a few days of reading Machiavelli and Thucydides might provide him with a clue or two. (Beginning with Chapter 23 of The Prince: “How Flatterers are to be Shunned.”)

Two: The independent television channel La7 (Channel Seven) is stealing viewers from all the other channels—all but one of which are controlled directly or indirectly by Berlusconi—by providing real news, and forcing the speakers on its talk shows to observe the basics of civil behavior. (The norm on the other channels is for everyone to shout at once, except Umberto Bossi, head of the Northern League, whose speech is impaired by a stroke—but his middle finger is fat and fit). Its evening newscast is conducted by Enrico Mentana, who has worked in the past for both the RAI state TV and Berlusconi’s Channel 5.

Three: Gianfranco Fini, the President of the lower house of Parliament, used a speech on September 4 to break publicly with Berlusconi in a way that brooks no return. (At one point he likened the prime minister’s actions to the “worst kind of Stalinism”—a formulation guaranteed to needle a Prime Minister who has continued to inveigh passionately against Communists for all these years since 1989.) More significantly, this break comes in the aftermath of an initial rift between the two last spring, which culminated in an all-out smear campaign against Fini in August, mounted by Berlusconi’s pet newspapers, the ironically named Libero (“Free”), and Il Giornale (“The Newspaper”). Berlusconi’s dossiers, like those of former Prime Minister Giulio Andreotti, are supposed to be the terror of every politician in Italy; but when Libero and Il Giornale trumpeted a real estate transaction in Montecarlo involving the brother of Fini’s companion Elisabetta Tulliani, the scandal looked a little scant.

There is nothing quite as counterproductive as a frontal assault that turns into an anticlimax: think of that opening scene in Gladiator, when Russell Crowe as the Roman general Maximus says “unleash Hell” on the Germans as the catapults start slinging their fiery bolts into the forest—and then imagine some German in a sleek tuxedo (or Jeremy Irons as Claus von Bülow) emerging from the smoke and saying, cool as you please, “They create a desert and call it peace,” or Romani ite domum, bitte. As Machiavelli says, in chapter 3 of The Prince: don’t take revenge unless you are absolutely sure of the results. Otherwise, one may be left, as the Prime Minister is now, wondering out loud what to do next. Perhaps he might start by following up on some of the promises he made in the campaign of 2008: for example, fixing the slow economy (at last count, Italy ranked between Lithuania and Poland, dead last among the G7 countries).

Il Corriere della Sera

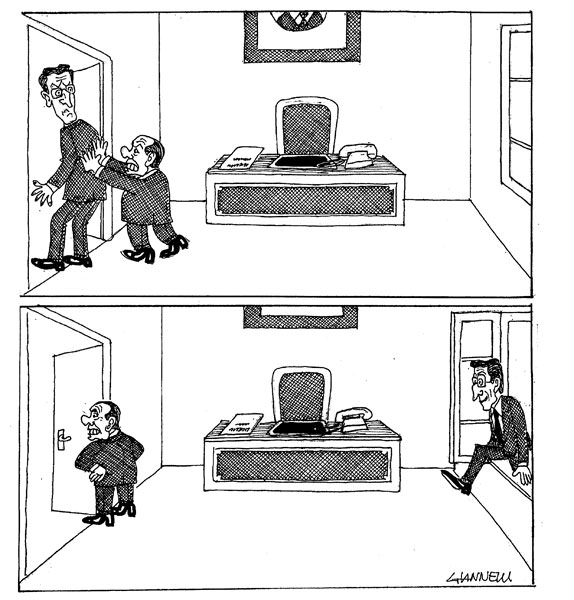

A cartoon by Emilio Giannelli for the Italian daily Il Corriere showing Silvio Berlusconi trying to push Gianfranco Fini out of his office, September 6, 2010

In any event, Berlusconi is no longer in control of Italy (it has been clear at least since his wife announced that she was divorcing him a year ago that he has lost control of himself); he may even have lost touch with his own times. Over the course of the summer, two brave, stubborn old-style statesman, the courtly President of Italy, Giorgio Napolitano—a former Communist—and the implacably cool Gianfranco Fini—a former Neofascist—have united to insist that Italy is a constitutional democracy rather than a populist circus, and that insistence (along with their very different but exceptional abilities to bide their time) has confounded a Prime Minister no longer accustomed to being confounded. Then, as a proper climax to a saga rooted from beginning to end in video, Channel Seven has emerged as a public forum in which people are compelled to reason together rather than try to shout each other down. Rumor has it that Berlusconi punched his TV set when he watched Fini’s interview with Channel Seven News on September 7. Clutching a copy of the Parliament’s Rules of Order, Fini calmly observed that Berlusconi could never carry out his most recent round of threats; to do so would only expose the Prime minister as “an illiterate about the Constitution.”

Advertisement

While the future of Italy, and of its present government, are impossible to predict precisely, the outlook is far from rosy for most of the nation. During this same week, the Camorra (the Neapolitan Mafia) announced their arrival in a southern Italian town by gunning down the town’s remarkable mayor, an honest, forward-thinking fisherman named Angelo Vassallo. And a meeting of the opposition center-left Democrats spun out of control, first with catcalls, then with smoke canisters, flying chairs, and fisticuffs; jobs are scarce, and tempers are frayed. Meanwhile, the burden of the struggling economy is felt by every stratum of Italian society but the very top. Still, that all this, and much else, is being discussed on a serious independent television channel—something that seemed impossible only a few weeks ago—has meant that an unexpected whiff of civility has come in on the first crisp winds of autumn.