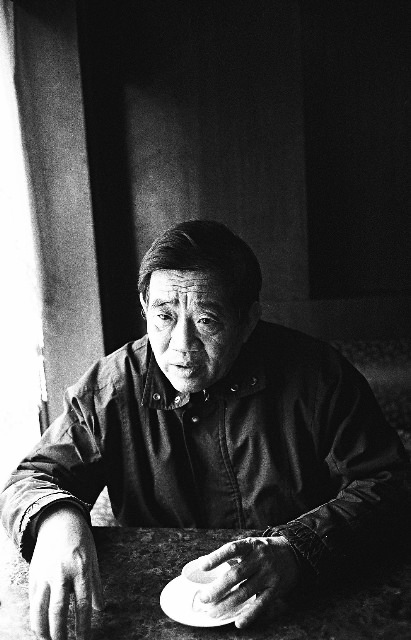

Yang Jisheng is an editor of Annals of the Yellow Emperor, one of the few reform-oriented political magazines in China. Before that, the seventy-year-old native of Hubei province was a national correspondent with the government-run Xinhua news service for over thirty years. But he is best known now as the author of Tombstone (Mubei), a groundbreaking new book on the Great Famine (1958–1961), which, though imprecisely known in the West, ranks as one of worst human disasters in history. I spoke with Yang in Beijing in late November about his book, the political atmosphere in Beijing, and the awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize to Liu Xiaobo.

Tombstone, which Yang began working on when he retired from Xinhua in 1996, is the most authoritative account of the Great Famine. It was caused by the Great Leap Forward, a millennial political campaign aimed at catapulting China into the ranks of developed nations by abandoning everything (including economic laws and common sense) in favor of steel production. Farm work largely stopped, iron tools were smelted in “backyard furnaces” to make steel—most of which was too crude to be of any use—and the Party confiscated for city dwellers what little grain was sown and harvested. The result was one of the largest famines in history. From the government documents he consulted, Yang concluded that 36 million people died and 40 million children were not born as a result of the famine. Yang’s father was among the victims and Yang says this book is meant to be his tombstone.

Over the past few years, foreign researchers and journalists have used demographic and anecdotal evidence to arrive at similar estimates. But Yang has gone further, using his contacts around the country to penetrate closely guarded Communist Party archives and uncover more direct proof of the number of dead, the cases of cannibalism, and the continued systematic efforts of the state to cover up this colossal tragedy. This makes Tombstone one of the most important books to come out of China in recent years and led the government to ban it.

Ian Johnson: I wondered when reading Tombstone why officials didn’t destroy the files. Why did they preserve all this evidence?

Yang Jisheng: Destroying files isn’t up to one person. As long as a file or document has made it into the archives you can’t so easily destroy it. Before it is in the archives, it can be destroyed, but afterwards, only a directive from a high-ranking official can cause it to be destroyed. I found that on the Great Famine the documentation is basically is intact—how many people died of hunger, cannibalism, the grain situation; all of this was recorded and still exists.

How many files did you end up amassing?

I consulted twelve provincial archives and the central archives. On average I copied 300 folders per archive, so I have over 3,600 folders of information. They fill up my apartment and some are in the countryside at a friend’s house for safekeeping.

As a Xinhua reporter did you have more latitude to explore the archives?

When I started I didn’t say I was writing about the Great Famine. I said I wanted to understand the history of China’s rural economic policies and grain policy. If I had said I was researching the Great Famine, for sure they wouldn’t have let me look in the archives. There were some documents that were marked “restricted” (“kongzhi” in Chinese)—for example, anything related to public security or the military. But then I asked friends for help and we got signatures of provincial party officials and it was okay.

Were people sympathetic to your task?

Yes, there was an elderly staff member in one archive, for example. My guess is that he also lost family members in the Great Famine; when I asked for relevant archives, he just closed one eye and let me look. I reckon he held the same view as I: that there should be an accounting of this matter. Like me, he’s a Chinese person, and people in his family also starved to death.

Why are you the first Chinese historian to tackle this subject seriously?

Traditional historians face restrictions. First of all, they censor themselves. Their thoughts limit them. They don’t even dare to write the facts, don’t dare to speak up about it, don’t dare to touch it. And even if they wrote it, they can’t publish it. And if they publish, they will face censure. So mainstream scholars face those restrictions.

But there are many unofficial historians like me. Many people are writing their own memoirs about being labeled “Rightists” or “counter-revolutionaries.” There is an author in Anhui province who has described how his family starved to death. There are many authors who have written about how their families starved.

Advertisement

The government admits the fact that some people starved to death. Is mentioning starvation really a sensitive topic half a century later?

The government says the famine was caused by “three difficult years” (natural disasters), the Sino-Soviet split (of 1960), and by political errors. In my account I acknowledge that there were natural disasters but there always have been. China is so big that there is some kind of natural disaster every year. I went to the meteorological bureau five times, looked at material and talked to experts. I didn’t find that climate conditions in those three years were significantly different from that of other periods. It all seemed normal. This wasn’t a factor.

What about the Sino-Soviet split?

It had no impact. The Soviets’ break with China was in 1960. People had been starving to death for more than a year already. They built a tractor factory and that was finished in 1959. Wouldn’t that have been a help to Chinese agriculture rather than a hindrance?

So what can account for starvation on such a vast scale?

The key reason is political misjudgment. It is not the third reason. It is the only reason. How did such misguided policies go on for four years? In a truly democratic country, they would have been corrected in half a year or a year. Why did no one oppose them or criticize them? I view this as part of the totalitarian system that China had at the time. The chief culprit was Mao.

In your introduction to Tombstone, you said that the Chinese Communist Party destroyed traditional values. Did this facilitate the Great Famine?

Traditional values involve valuing life, valuing others, not doing unto others what you don’t want done to yourself. All of these values were negated. From 1950 onward, the Communists criticized the passing down of traditional values. There was a moral vacuum.

When do you think we might see Cultural Revolution-era archives opened up?

It is still early to talk about that. Overseas, many good books have been written about the Cultural Revolution. I have bought many and brought them back. Within China, there’s not a single good book on the topic.

That seems like something you should pursue.

In fact, I am planning a book on the Cultural Revolution. I am collecting material but don’t yet know exactly how I will write it. I am still trying to figure that out.

You also work for Annals of the Yellow Emperor. People say it has been under pressure.

There is some pressure of late. There were the events surrounding Wen Jiabao’s recent speeches and the Liu Xiaobo prize. There has been a backlash. They did not allow Wen’s interview with CNN to be published in the domestic media. [In the interview, which was published on September 29, Wen stated that “for any government, what is most important, is to ensure that its people enjoy each and every right given to them by the constitution,” which many reform-minded Chinese took as a signal that the country would try to live up to its constitutional protections on free speech and democracy.] We ran the full text in our magazine—we didn’t miss one word—and were censured. But that issue of our magazine was not banned; it continued to be distributed.

Why do you think your magazine seems to enjoy more leeway than other Chinese publications?

Because we know the boundaries. We don’t touch current leaders. And issues that are extremely sensitive, like 6-4 [the June 4th Tiananmen Square massacre], we don’t talk about. The Tibet issue, Xinjiang, we don’t write about them. Current issues related to Hu Jintao, Jiang Zemin and their family members’ corruption, we don’t talk about. If we talk just about the past, the pressure is smaller.

Do you feel this year’s political climate is tighter?

Usually when the Communist Party feels a sense of crisis, it will spark a backlash. Liu Xiaobo winning the Nobel Prize is a slap in the face for the Chinese government. On the date of the announcement of the prize, October the 8th, Voice of America called me for an interview. I said it was a good thing for the long-term prospects of democracy in China. It’s a good thing, I said, but also don’t over-estimate the impact; China doesn’t yield to external pressure, and there will be a backlash. And now what we are seeing is the backlash.

From a long-term perspective, it might have some inspiring effect on the progress of democracy in China. But within China, Liu is not well-known. He won’t have the same effect as Gorbachev or Havel did, for instance. And the backlash is strong. Many Chinese intellectuals can’t leave the country now, and their family members too. They’re being very strict.

Advertisement