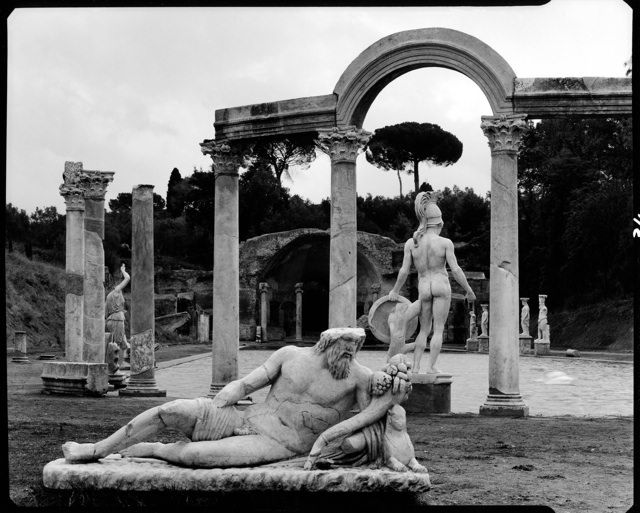

I first went to Hadrian’s Villa, the incomparably beautiful rural residence of that most cultured of all Roman emperors, in 1967 with my father. I was a teenager for whom the long country road from Rome to the spa town of Tivoli seemed endless, and endlessly mysterious. It was impossible for a California kid to know what to expect beforehand, and expectation could never have rivaled the marvel of the real thing—its age, its beauty, and my father’s excitement, as informed as mine was formless. We climbed over vaults and crept through tunnels, watched the swans and carp navigate the murky green waters of the imperial reflecting pools, drank in the quiet and the breezes that softened the summer heat. We ate lunch under a grape arbor attached to Tivoli’s fifteenth-century castle as a mandolin played “Lara’s Theme” from Dr. Zhivago, and then went on to the crazy fountains of Villa D’Este; including the one you could walk through and the startling apparition of the gray stone goddess Artemis of Ephesus, squirting water from each of her twenty-two breasts.

If local and regional officials get their way, the villa may soon be remembered less for its ancient pleasures than for the stench of modern refuse wafting through its ruins. On May 23, Italian Prime Minister Mario Monti ratified the decision of the Prefect of Rome to locate the new city dump in an abandoned quarry near the village of Corcolle and, as it happens, just a few hundred meters from the villa. Outraged opposition from archaeologists, the preservationists of Italia Nostra, and common citizens who gathered at the site wearing red paper hearts pinned to their chests averted the threat on May 25, but since then, the Governor of Lazio Region, Renata Polverini, has once again endorsed the Tivoli site as the proper place for the garbage of Rome, giving new cause to Paolo Conti’s warning in the Corriere della Sera of May 24 that “Corcolle will become the next target for all the criticism leveled internationally against our country.”

Millions of people all over the world have had virtually the same experience at Hadrian’s Villa as I did in 1967, and harbor virtually the same memories; the villa—now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, whose olive grove still produces oil from its millennial trees—is part of their lives, and not necessarily a negligible part. In my own case that three-week trip to Italy helped to determine the shape of my life, and I have traveled up and down the Via Tiburtina for most of the subsequent forty-plus years, the trip ever shorter as it becomes an increasingly tiny fraction of my lengthening span.

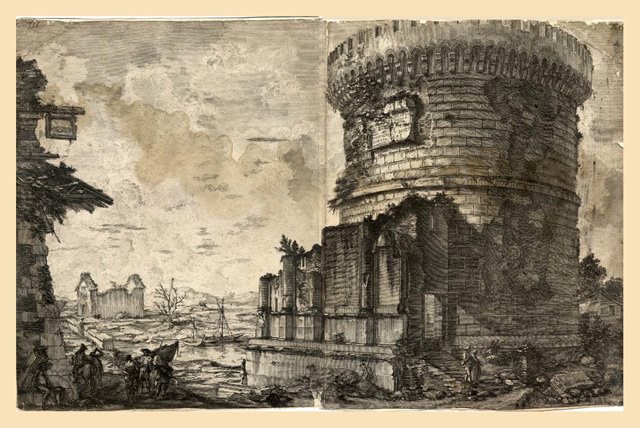

In that time, I have watched as factories and suburbs devoured the countryside as if it were infinitely renewable, or infinitely unimportant. The idyllic riverside Tomb of the Plautii Urgulanii—a round tower of travertine dating from the time of Caesar and Cicero, a favorite of nineteenth-century Romantic artists and micro-mosaicists—was imprisoned in the unromantic late twentieth century behind a concrete wall at an ugly crossroads, the once-limpid pool beside it channeled into huge metal pipes.

The encroaching city has also affected the way we get to Tivoli. The public bus used to take off from the area of Termini station (my friends and I used to “meet at the banana stand”); now, because the Via Tiburtina has turned into a commuter route, the bus has been relegated to a stop at the end of the B subway line, in a no-man’s-land of urban sprawl extending nearly all the way to Hadrian’s Villa (strangely enough, the autostrada is now the more rural route from Rome to Tivoli, with glimpses of a unspoiled countryside). Because every Italian who can uses a private car, the passengers on the public route have become less savory; twelve years ago, after an Italian skinhead began throwing his weight around the back of the Tivoli bus, I sat by as a Bengali sold a switchblade to a Rumanian, who promptly tried out his purchase on the head rest of the seat in front of him. They were nice enough young men, but the skinhead scared them and they all scared me. The Italian term for this state of things is degrado, a perfect description. If only naming a phenomenon led to doing something about it.

Not every change between Rome and Tivoli has been for the worse: Hadrian’s Villa is more carefully tended than it was in earlier years, a little museum has been set up on site with an interesting series of temporary shows (the current one is about Antinous, the Bithynian youth and Hadrian favorite), and up until this summer the Villa Adriana summer arts festival opened the site at sunset for music and drama. But now the funds for the festival have been cut, and instead we can imagine the dump at Corcolle providing Hadrian’s refuge with new smells, seepage, and wheeling gulls to squawk with the swans over the emperor’s private version of the Vale of Tempe, the shady Greek valley that was the legendary home of the Muses. Gulls are all very fine at the seashore, but perhaps not in the olive trees of Villa Adriana. Not there, where in 2007, my father, forty years after our first trip, showed the first signs of his final illness.

Advertisement

Initially, it seemed, Rome would come to its senses: when the Corcolle dump plan was ratified on May 23, it met with such immediate and widespread outrage in Italy alone that on the following day the decision was revoked, and the prefect responsible for the decision (appointed by former Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi) resigned. In the following weeks, however, vehement protests by residents of the areas proposed as alternative locations have led Governor Polverini once again to endorse the Tivoli site. In desperation, apparently, the mayor of Rome has contacted the new mayor of Naples, Luigi De Magistris, for advice about what to do with his mountains of refuse. De Magistris solved the problem of Neapolitan garbage (where one hare-brained scheme called for throwing the whole mess into the maw of Vesuvius) by shipping it all to the Netherlands. Governor Polverini continues to tout the Corcolle site.

A petition to cancel that plan has gained thousands of signatures, and Tivoli itself is full of angry signs. If only the Muses of Tivoli could rise up from Tempe now, and give the friends of Hadrian’s Villa the voice of Stentor and the eloquence of Demosthenes, then, perhaps, we could begin to save what is left of our universal heritage from the rapacity of the real estate moguls who have paved over huge tracts Italy’s incomparable, irreplaceable countryside—and from the cultural cluelessness of the Italian officials who can think—even for a moment—that a dump is fair exchange for an earthly paradise.