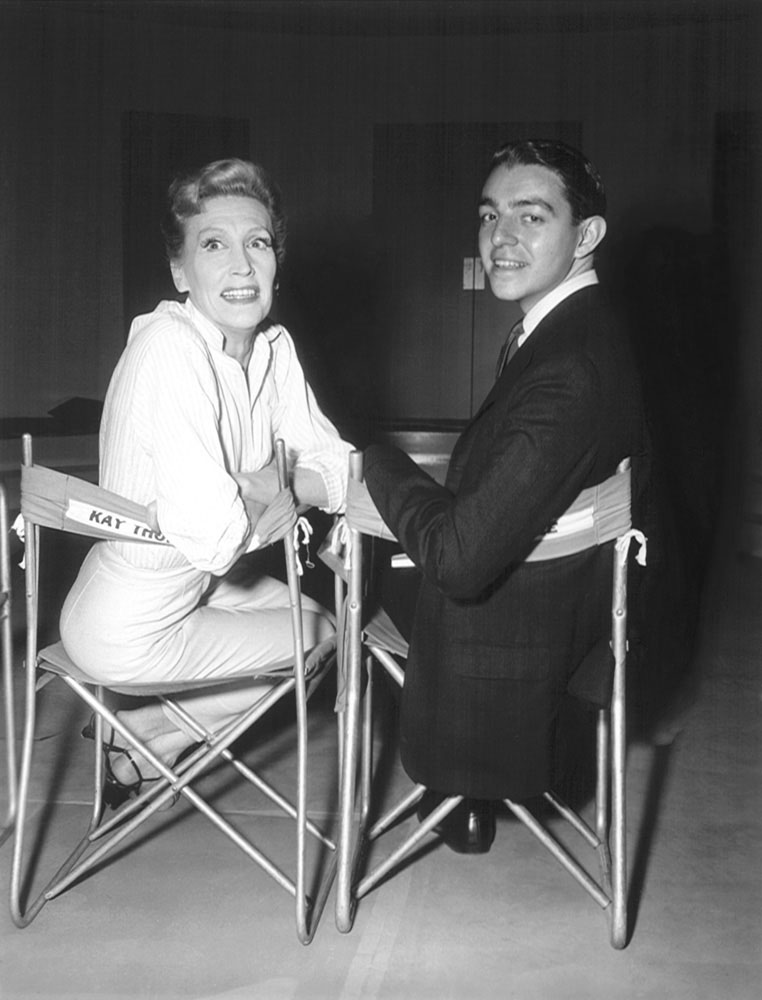

Eloise, the children’s literature star—she of the Plaza, Paris, and Moscow—was born of Kay Thompson, not otherwise an author. Thompson (1909–1998) was a musician, singer, and comedian, most widely remembered for her brassy, bossy turn as a magazine editor in the film Funny Face (“Think Pink!”). She was also a behind-the-scenes force for years as a voice coach (for Judy Garland and Frank Sinatra, among others) and vocal music arranger in Hollywood.

Hilary Knight was a young illustrator just getting started in books and theater posters in New York when a mutual friend introduced him to Thompson, whose “Eloise” character had become a staple of her song-and-patter nightclub act in the early 1950s. When they combined their efforts, the Eloise we know emerged. A classic Hotel Child who has spurned the role of Waif for that of Trickster, she’s all alone in the world except for her nanny, making endless mischief throughout the Plaza and speaking to us in an exaggerated but rapid drawl, like an Upper-East-Side matron on speed, her words presented to us on the page as antic free verse: “If there is an Exit sign I always have to go into it because there/might be a mattress in there and I can lie down on it and get some/rest so I can carry on for Lord’s sake/Oh my Lord I am absolutely so busy I don’t know how I can possibly/get everything done.”

At first, the manuscript of Eloise seemed unlikely to succeed, in part because the creators declined to let it be categorized as a children’s book, and subtitled it instead, coyly, “A book for precocious grown-ups.” But once published in 1955, this apparently narrow in-joke creation of Manhattan sophisticates charmed a larger world as well. And, like many books beloved by children (and precocious, or arrested, adults), Eloise’s appeal still seems strongest as a tightly held, private connection between the reader and the character. “Oh, I love Eloise!” many people have said to me when I told them I was writing about her. Then they narrowed their eyes at me—and I knew they were thinking, as I was, “But she’s not yours; she’s mine.”

There’s currently an Eloise revival, in the form of a new museum show emphasizing Knight’s contributions, first mounted at the Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art in Amherst, Massachusetts, and now in a slightly different version, “Eloise at the Museum,” at the New-York Historical Society until October. And in 2015, a peculiar documentary, It’s Me, Hilary: The Man Who Drew Eloise, made by Matt Wolf with Lena Dunham as a kind of host-interviewer at the illustrator’s Connecticut home, aired on HBO. Dunham displays her own Eloise tattoo and Eloise hair-bow, and has declared deep connection with the character (she calls her “a feminist even though she may not know the word yet”).

And yet despite the efforts of publishers, promoters, and indeed of Kay Thompson herself, I cannot bring myself to regard Eloise as any sort of cute. She has always been too much, all hilarious, monstrous id—but one gathers that it was in the interests of her marketers to pretend that she was also adorable, hence in some way acceptable to American taste. There have been various Eloise dolls, and Eloise toys and games, many of which are on view in the museum show. The only item that stirred a child’s longing in me was an Eloise suitcase, packed with necessities that included socks and a toothbrush. (I looked in vain for sunglasses and a champagne bottle.)

Thompson’s complicity in the “cute” version of Eloise—or perhaps I mean her mixed feelings about her creation—is also on display in the museum show. She may always, in fact, have envisioned her character, like Fanny Brice’s Baby Snooks, as a kind of slapstick vaudeville turn, or a slightly naughty Shirley Temple. At the museum display, one is invited to pick up an old-fashioned telephone receiver and listen to a recording of Bernadette Peters, from the 2015 audiobook, lisping, “Hello, it’s me, Eloise, I am six and I live at the Plaza in New York,” in a really horrible version of a child’s voice. There’s also a wobbly video available online from the 1950s, after the Eloise books first became successful, when Kay Thompson was the headline act in the Plaza’s Persian Room. Singing a very conventional, soupy song about “the little girl/who lives at the Plaza in New York,” Thompson croons and mugs while a very fetching child actress parades around and eventually kisses the grownups goodnight before heading off to bed. Eloise kissing the grownups! Please. At most, she might have deigned to allow a waiter she fancied to kiss her hand.

Advertisement

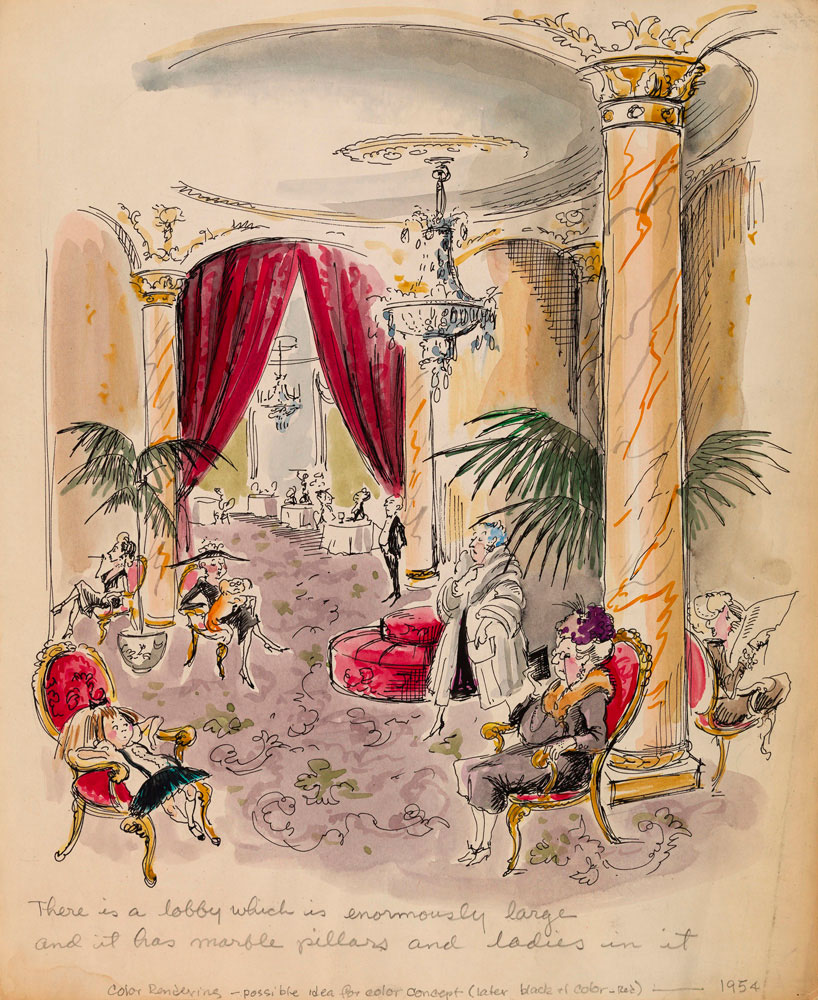

All of this leads me to suspect that the books may have involved a swerve away from Thompson’s original baby-voiced creation. “The little-girl voice emerged in her teens, according to her sister Blanche,” writes Jane Bayard Curley in the catalog for the Carle exhibition. “Eloise stems directly from the tradition of comic vaudeville stars pretending to be children….Music was her profession, but words were the playground where her wit danced.” On the page, however, the voice does not cloy—and at its pinnacle, in Eloise in Paris, it becomes positively vatic: “Here’s the thing of it/Clink clank hang up that phone/and simply send a cable”; “Or you can go to the Flea Market/Voici what they have there/this red feather fan/or this fur piece/or this wedding dress/or these elephant tusks/if you need something like that/and quite a lot of other rawther valuable things/I got two champagne corks/and had them shipped back to the United States/They were rawther a bargain.”

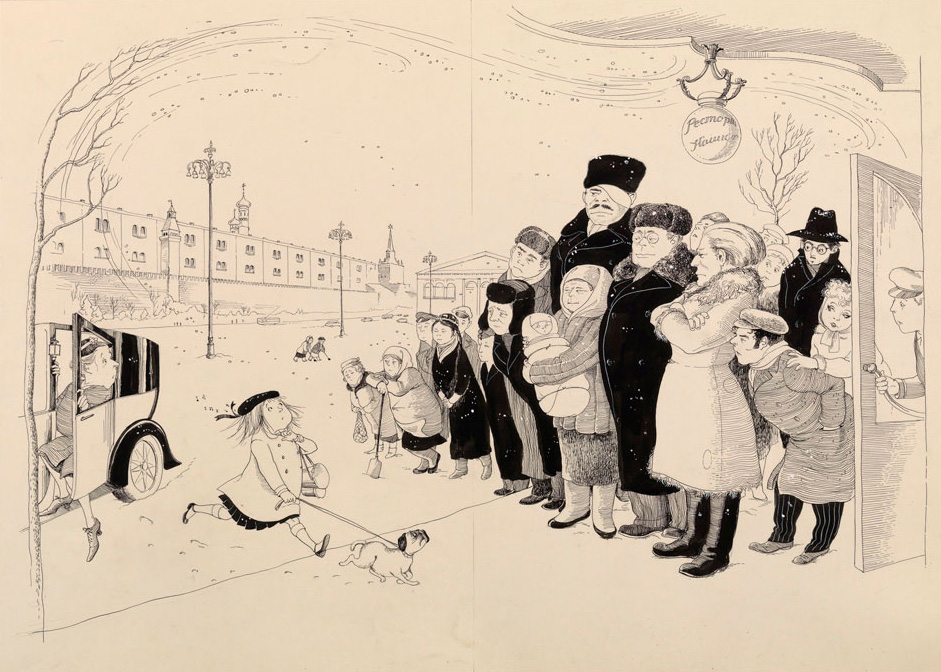

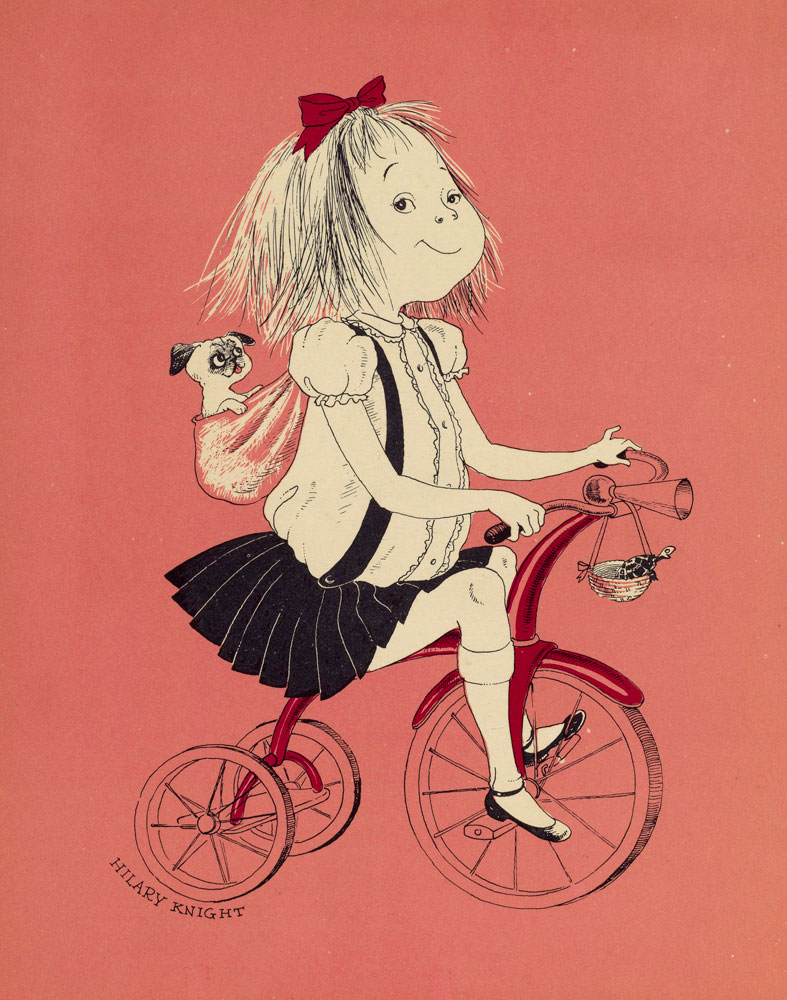

One feels that Knight’s line drawings, which display more movement, verve, and surprise than most actual animations, must have had something to do with that acerbic turn. What Knight captures is the essential misfit quality of Eloise. Gleeful, greedy, prone to random acts of violence—although she is never malicious—loquacious and haughty, this is no mere six-year-old; she is scarcely human, and not especially female. Knight drew her with an unpretty imp’s face; wind-blown hair; a pleated skirt held up by suspenders over a white blouse, pink ballooning underpants (very important, as she is often upside-down), rucked-down bobby socks, and Mary-Jane shoes with the straps flying. Standing, she thrusts out her modest pot-belly above spindly legs, cutting a figure that certainly does not resemble what plump children really look like.

Eloise is more like a feral Truman Capote, yammering on the phone and terrorizing the staff of the Plaza while knowing others will tidy up the mess. She is also very funny—wedging langoustine shells onto her fingers as long nails, evading the barber’s scissors, stealing food, playing with the elevator, wearing an eggcup as a hat. She has her own verbs: sklathe, skibble, skidder, slomp, swiggle, sklonk. “Every Wednesday I have to go to the Barber Shop/and have Vincent shape my hair…./Sometimes I sklonk him in the kneecap.”

The main reason I loved her, and I did, was that in addition to new verbs she offered to my thwarted child’s state a vision of unchecked imperial power. And that power was wielded, at least nominally, by a girl. She could pick up the phone, and people brought food; she could keep any pet she wanted; no damage was paid for, no mischief ever punished; the maze of adult rules in the Plaza, or the city of Paris, was no more daunting than an amusement park, with the added thrill that one could break things. Look again at the tummy, and the three-quarter stance Eloise takes, say, when posed for her portrait that hangs in the lobby of the Plaza to this day. Knight has envisioned Eloise as an eighteenth-century lord, a landholder gesturing toward his realm—where presumably he can break anything he wants, call for unlimited eats, and generally romp as he likes.

“Eloise at the Museum” is at the New-York Historical Society through October 9.