“Melville’s second son, Stanwix, was born a few weeks after the publication of Moby-Dick. He is a puzzle…”

—Elizabeth Hardwick, Herman Melville

“I believe that no materials exist for a full and satisfactory biography of the man.”

—Herman Melville, “Bartleby, the Scrivener”

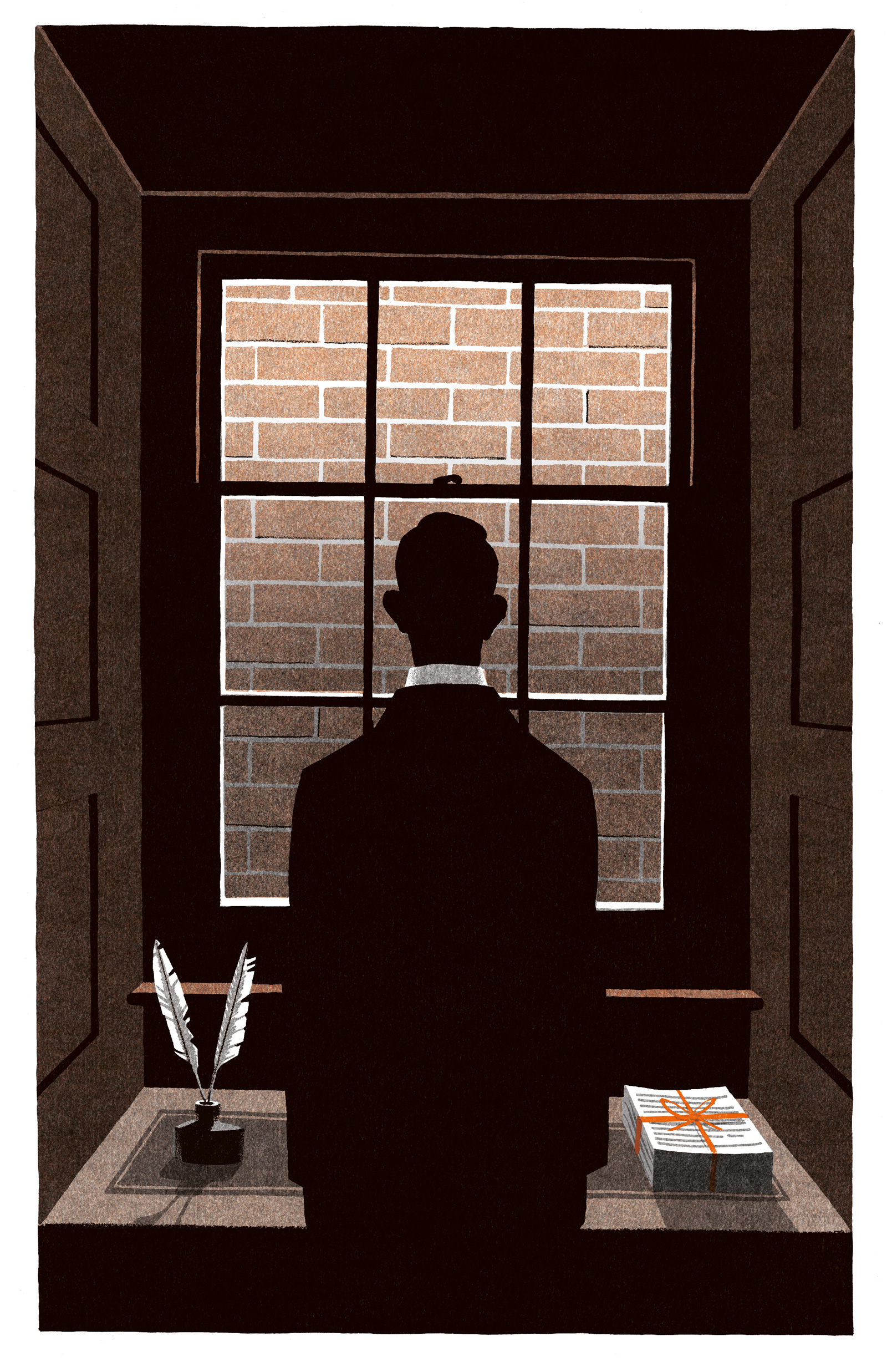

I was teaching “Bartleby, the Scrivener” to a dozen undergraduates on a cold November morning, all of us a little haggard after an unexpected Halloween snowstorm. Distractedly, I glanced across the page to the editor’s headnote, and settled on these words: “Their second son, Stanwix… was found dead in a San Francisco hotel in 1886.” I found myself thinking what a strange name Stanwix was, more like a commercial brand than a given name. Stanwix: When Kleenex Isn’t Enough. And what, I wondered, was Stanwix found dead of? Did he blow his brains out, or was that another of Melville’s star-crossed sons? During the days that followed, I began to assemble a few stray notes on Stanwix. I was following a thread, as I imagined it. And yet, the thread didn’t seem to lead out of a maze, like Ariadne’s, but farther into it.

I assumed that Stanwix—one of those “lesser lives” that, as Diane Johnson has pointed out, don’t feel any less to those living them—had been accorded a very small place in Herman Melville’s biography, which turned out to be true. But I wanted to stave off this kind of limitation in my own thinking. For this reason, the book I most consulted, or rather wandered around inside, was Jay Leyda’s The Melville Log (1951). During the 1930s, Leyda had traveled to Moscow to work with the great filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein. On his return, he wrote the standard history of Russian and Soviet cinema. Leyda tried to get a foothold in film production, but he was blacklisted in Hollywood. Unemployed, he took up a project initially conceived as a birthday gift for Eisenstein, a Melville enthusiast: a collage, or montage, of the known documents of Melville’s life. Leyda wanted to give each reader the chance “to be his own biographer of Herman Melville.” Later, Leyda did something similar in The Years and Hours of Emily Dickinson (1960).

It was during the centenary of Dickinson’s death, in 1986, that I first came to know Leyda, a shy and formal man, when he was an emeritus professor of film at NYU. The floor of his apartment was covered at the time with documents, assembled for an expanded version of The Melville Log, undertaken with the Melville scholar Hershel Parker. I told Leyda how much I admired an article that he had published, in 1953, about one of the Irish servants in the Dickinson household, Margaret Maher.

It occurs to me now that my pursuit of Stanwix, another obscure life lived on the margins of fame, resembles Leyda’s work on “Miss Emily’s Maggie.” I imagine myself crawling around on Leyda’s apartment floor, searching among the piles of documents for stray mentions of Stanwix.

“Small and thin,” Stanwix Melville was born on October 22, 1851, between the British publication of Melville’s sixth novel, under the title The Whale, on October 18, and its American publication, about three weeks later, as Moby-Dick. The novel itself is notably careful about naming: Ahab, Ishmael, Queequeg, Starbuck. Call me Stanwix.

Stanwix was burdened with a name linked to an illustrious ancestor. In 1777, at a pivotal moment in the American Revolution, forces under the command of Peter Gansevoort held off a siege by British troops at Fort Stanwix, a star-shaped fort built around 1758, in upstate New York, under the direction of the British General John Stanwix. Gansevoort was Herman Melville’s grandfather. And yet, at the time that Gansevoort defended it, Fort Stanwix had already been renamed Fort Schuyler, for an American general. Melville’s choice for his son’s name seems perversely self-defeating. Why wasn’t Stanwix named Schuyler, a good Dutch name like Gansevoort, for the victors?

A hundred years later, Herman Melville stopped by the luxurious Gansevoort House in Greenwich Village, and casually asked about the origins of the name. “A wealthy landholder in the area,” came the response. The hero of Fort Stanwix, forgotten! “The dense ignorance,” Herman fulminated in a letter to his mother, “of this solemn gentleman,—his knowing nothing of the hero of Fort Stanwix, aroused such an indignation in my breast, that, disdaining to enlighten his benighted soul, I left the place without further colloquy.”

On Stanwix’s birth certificate, in the spaces reserved for the newborn child’s parents, Herman Melville signed his name, as required, and then, unaccountably, the name of his own mother. While Stanwix was nursing, his mother, Elizabeth Shaw Melville, developed a painful inflammation in her breast. Hershel Parker speculates that sexual deprivation likely ensued for Herman Melville. The more obvious deprivation was Stanwix’s, whose early weaning entailed both a loss of intimacy with his mother and, presumably, a diminished resistance to disease later in life.

Advertisement

A childhood photograph from around 1860 shows a pale, thin, unsmiling boy, with an oversized, almost clownish, bowtie. “Papa took me to the cattle show grounds to see the soldiers drill,” Stanwix wrote his aunt on June 20, 1861, “but we did not see them, because one of the factories was on fire, it was too bad. But papa took me [on] a ride all through the Cemetary.” Soon, the whole country was taking a ride through the cemetery.

In 1863, the Melville family left its “square, old-fashioned” (Stanwix’s adjectives) home in Pittsfield, Western Massachusetts, and moved to New York City, where Herman took a modest position in the Custom House. His novels, especially Moby-Dick, had been ridiculed by reviewers and ignored by readers. Henceforth, he would be a poet, as he embarked on his long, gloomy epic poem, Clarel.

In 1867, with the Civil War a recent memory, Stanwix’s older brother, Malcolm, joined a volunteer regiment. He was so smitten with his pistol that, according to a newspaper report (citing Stanwix), he slept with it under his pillow. Malcolm returned from a party at three o’clock one morning. He slept late. Let him sleep, said his father, and be punished at work for his tardiness. In the evening, when Herman came home, they broke down the bedroom door. The boy was found dead of a gunshot wound to the head. “Mackie never gave me a disrespectful word in his life,” his father declared, “nor in any way ever failed in filialness.”

In 1869, Stanwix announced that—like his father before him—he wanted “to go to sea, & see something of the great world.” Augusta Melville, Herman’s sister, added: “Herman & Lizzie have given their consent, thinking that one voyage to China will cure him of the fancy.” (One voyage did not cure Herman Melville of his fancy.) On April 4, the Yokohama, with seventeen-year-old Stanwix aboard, sailed for Canton. He wrote from Shanghai a few months later. Life at sea agreed with him, he said. A few weeks later, news reached his family that he had jumped ship in England. “What have you heard of Stanwix Melville [and] from what point did he run away?” asked one of Herman’s cousins. Suddenly, unannounced, Stanwix showed up in Boston, “much taller & stouter.”

In 1871, Stanwix was off again, to a small town in Kansas. Searching for work, he drifted down through Indian lands, followed the Arkansas River to the Mississippi, and arrived in New Orleans. “I found that a lively city, but no work,” Stanwix wrote, “so I thought I should like a trip to Central America, I went on a steamer to Havana, Cuba & from there to half a dozen or more ports on the Central America coast till I came to Limon Bay in Costa Rica.” Buoyed by rumors that a canal was soon to be cut through Nicaragua, he set out on foot from Limon Bay, “I walked from there on the beach with two other young fellows to Greytown in Nicaragua, one of the boys died on the beach, & we dug a grave in the sand by the sea, & buried him, & travelled on again, each of us not knowing who would have to bury the other before we got there, as we were both sick with the fever & ague.”

Having avoided a grave by the sea, Stanwix almost found a grave in the sea. He joined a surveying expedition on a schooner charting potential sites for the canal. “I got wrecked there in that heavy gale of wind,” he wrote. “and I lost all my clothes, & every thing I had, & was taken sick again with the fever, I went into the hospital there, & then came home on the Steamer Henry Chauncey, where I find the cold weather agrees with me much better, than the fun of the tropics.” Stanwix concluded: “Now I say New York forever.” But he discovered, like Bartleby, that failing eyesight was a “serious obsticle” to office work. And besides, he wrote, “I don’t like to be a clerk in an office.” (Bartleby: “No, I would not like a clerkship; but I am not particular.”) He sailed for California.

“He seems to be possessed with a demon of restlessness,” Stanwix’s mother remarked. But his real demon was motionlessness. After eighteen months in California, Stanwix reports: “I am still stationary.” After Bartleby’s employer suggests that he might consider “going as a companion to Europe, to entertain some young gentleman with your conversation,” Bartleby replies, “I like to be stationary.” To which his exasperated employer responds: “Stationary you shall be then.” Published two years after Stanwix’s birth, “Bartleby, the Scrivener” could not be based on Stanwix. But could Stanwix be based on Bartleby? Could Herman Melville, the distant, depressed father, have helped create the conditions for a Bartleby?

Advertisement

In 1876, Stanwix begged his half-uncle Lem for money. “There is a party of five or six of us that are going to start for the Black Hills country about the middle or last of January two of them who were there before & were doing well until driven away by the Indians, & I am going with them if I can get this money.” Then he added, presumably afraid of his father’s reaction, “Do not let anyone know of my intentions to go to the Black Hills.”

In the San Francisco directory, for April 1879, there is a listing for “Melville Stanislaus, canvasser.” Stanwix-Stanislaus was rounding up votes, for pay. Bartleby is evicted from his law-office lodgings on Election Day, and is consigned, fatally, to the Tombs.

Stanwix Melville died on February 22, 1886, age thirty-four, presumably of tuberculosis. So much was taken away during his short life: his mother, his namesake, his brother, his eyesight, his employment (many times), his health, his life. On March 16, his aunt Helen Griggs wrote to her cousin Catherine Lansing:

It is sad indeed to have had Stannie die away from home. But it seems he had a friend, who did all he could to make him comfortable, and there was money enough to procure all that was necessary for his comfort. It is sad enough; but it might have been worse, since there is so much consolation for his poor mother.

Ah me. The sorrows that lie round our paths as we grow older!

Ah Stanwix. Ah humanity.