The Wooster Group’s A Pink Chair (in Place of a Fake Antique) suggests what it might have been like to watch a ghost materialize on stage, called up by an early-twentieth-century medium. The ghostly presence summoned here is that of Tadeusz Kantor (1915–1990), the celebrated director and performance artist who profoundly affected modern theater, both in his native Poland and the wider world. In a program essay, Anna Burzyńska, a professor of theater, describes Kantor as a “shaman leading this theatrical rite of communication with spirits past. During performances he would sit on an old, damaged, squeaky chair, as if to emphasize that we are entering the private world of his memory, looking through his album of family photographs alongside him. He was Charon, the old ferryman of Hades, who carried his audience on his boat across the river of oblivion and into the land of the dead.”

Born in a small Polish-Jewish town, Kantor lived through both world wars. His father died in Auschwitz. Kantor witnessed the Communist era and the fall of Communism. Criticized by the government for making work that failed to promote Socialist Realism, Kantor left the stage and worked as a painter from 1949 to 1955, when he founded the Cricot 2 Theatre. His influence on Eastern European art has been compared to that of Joseph Beuys in Germany, and Andy Warhol here.

Kantor’s history haunts A Pink Chair, which extracts the high points from his play, together with selections from his writings, read aloud—in the production I saw last summer at Bard’s LUMA Theater—by the actor playing Kantor, Zbigniew Bzymek, also known as “Z.” We feel we are watching a drama about a man’s life lightly disguised as a play about a group of unusual characters gathered in what is sometimes Ithaca and sometimes a raunchy Polish country inn, where the merrymaking recalls the falling-down drunken bar-room dances in the films of the Hungarian director Béla Tarr. Because the Wooster Group is constantly changing and developing its productions, the versions of A Pink Chair that appear this spring may be different the from the one I saw at Bard, and watched during the preceding months, in rehearsal.

Atmospherically lit by Jennifer Tipton and Ryan Seelig, the set of A Pink Chair is strewn with the sort of ordinary objects that Kantor incorporated in his work. The desk chair on casters has never seemed a more efficient vehicle than when we see it transporting Z, whom a fisherman’s hat has transformed into Odysseus. A metal-table-on-wheels that one might find in a restaurant supply house becomes a throne for Suzzy Roche as a somnambulist Penelope. A simulation of waves—scalloped panels sliding from side to side—produce a stage effect like something from early vaudeville.

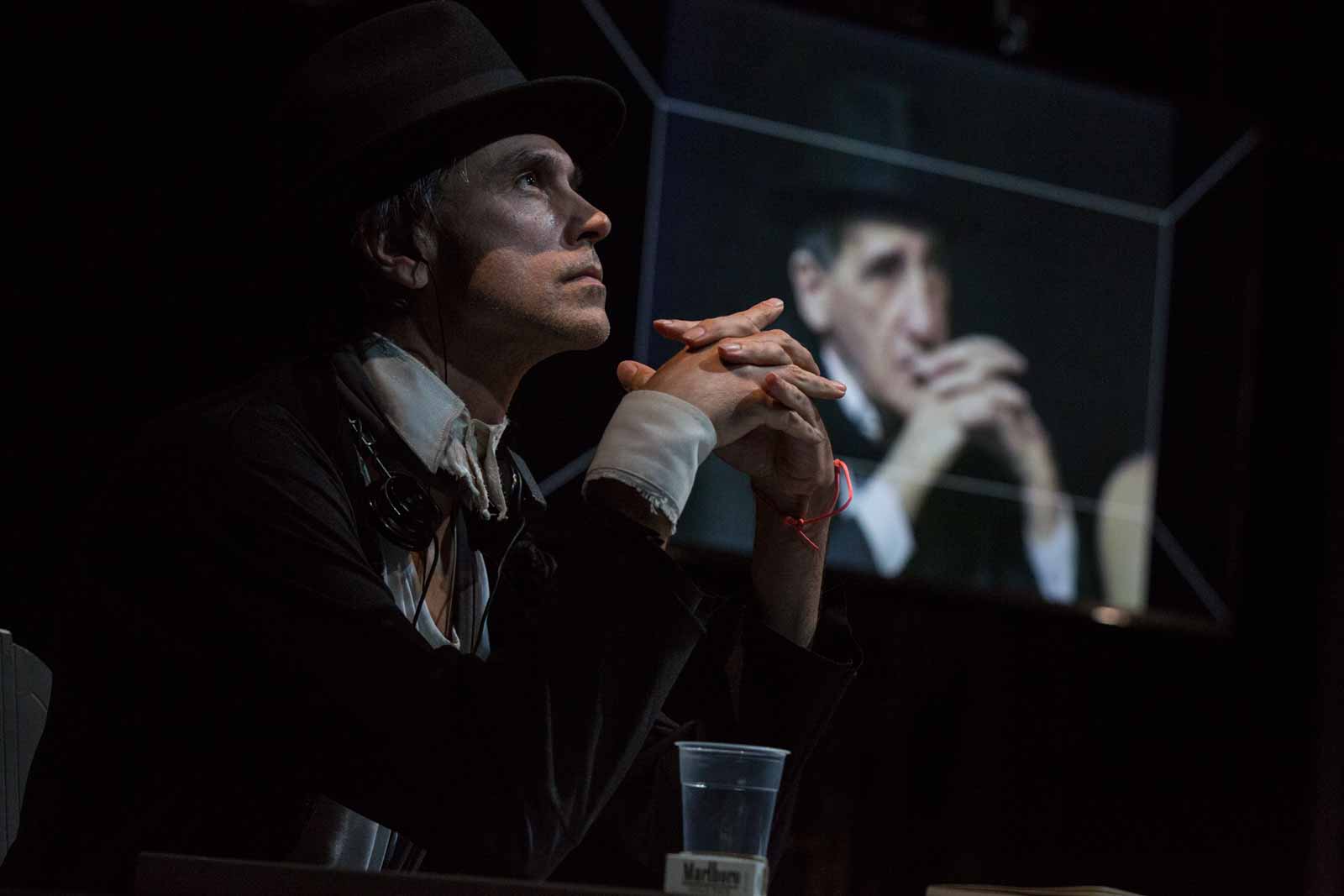

Projected on a screen behind the actors is archival footage of Kantor watching and directing his I Shall Never Return (1988), which in turn was partly based on the Polish playwright Stanisław Wyspiański’s 1907 Return of Odysseus. The Wooster Group actors have clear, if often ingeniously skewed or tweaked, correspondences to their counterparts in Kantor’s dreamlike play, which features a zombified mystical bride, a soldier, an innkeeper, a priest, a bar-room slut known as the Schlump, and mythical figures, including Odysseus, Penelope, and Telemachus. You can see the resemblances to Kantor’s original, but even when the actors on stage are doing some version of what’s occurring on film, it’s never merely imitative or reductive, never as simple as avant-garde karaoke.

Since its beginnings in Soho in the 1970s, the Wooster Group—directed by Elizabeth LeCompte in collaboration with her actors, some of whom have been with the group since its inception—have drawn on a wide range of sources for subject material: canonical plays, fragments of autobiography, a song cycle, an opera, early Shaker spirituals, The Crucible, The Emperor Jones, Tennessee Williams’s Vieux Carré, D.A. Pennebaker’s documentary film Town Bloody Hall, a baroque opera, La Didone, and a recorded phone conversation between Spalding Gray (a founding member) and his late mother’s psychiatrist. Their productions have often incorporated music, dance, film, and, more recently, technology like video projection.

The Kantor film is only one element in a production that is neither a tribute nor a recreation, but rather the theatrical equivalent of a free translation, not simply from Polish to English but from one artist’s language to another’s. Though hard to describe, the Wooster Group’s dramatic vocabulary explores the boundaries between chaos and control, the intersection of babble, noise, poetry, and wisdom. The group’s “plots” are non-linear, non-narrative, yet everything feels thought-out, connected, arranged for dramatic effect. The actor’s gestures and movements are often stylized and occasionally antic. (My earliest memory of a Wooster Group production is of Spalding Gray doing a manic dance with a lawnmower.) Though Wooster Group productions lack—and, in fact, subvert—the formal structures of exposition, climax, and dénouement through which drama usually operates on our intellects and our feelings, they deliver aesthetic and intellectual satisfaction, together with a cathartic emotional jolt.

Advertisement

The first face we see in A Pink Chair, Bzymek’s, is on screen. A young Polish actor and filmmaker, Z says he has been told he resembles Kantor, with whom he shares a dark, brooding aspect, although, in archival footage, Kantor appears not only older but considerably craggier and more haunted. On stage, both men affect slouch hats and romantically wrapped scarves. And as the play progresses, Z begins to look ever more like the Polish director. It’s not just their faces and posture; even their hands look alike. Yet Z’s performance never descends into impersonation; it’s too stentorian and peculiar. In Future Real Moments, a video collage of moments from rehearsals for this production available online, we see Z treating his colleagues the way one can imagine Kantor might have behaved. Z seems to have become him.

Besides the casting of Z, another of LeCompte’s wise choices was to include, early on, a video interview with Kantor’s daughter, Dorota Krakowska, herself a director. A lovely, middle-aged woman, Dorota is first seen chatting with actress and Wooster Group co-leader Kate Valk about the effects of eating sugar. Dorota speaks about her father with a tenderness and anguish that makes it clear how tormented he was by the events of his country’s history; indeed, it’s hard to imagine what we would make of Kantor without her intercession. She doesn’t tell us much about her father’s work, but what she says is eloquent and emotionally charged:

Now that I’ve watched it, I don’t know how many times, it’s really like a testimony. He was including maybe the most important things in his life. And he was the center of this, he is this spirit, but inside his head. There were a lot of things—dialogues from quasi heroes from his old performances. Also the people he worked with. Even his marriage. It was said once that maybe it was the marriage with my mother, and it doesn’t matter if it was or not. But this marriage, as a lost love. It was memory. An abstract marriage that was already dead… some symbolic want for an ecstatic love.

Eventually, Kantor’s posthumous collaboration with LeCompte includes a capsule version of Return of Odysseus, which culminates in one of the most striking episodes in A Pink Chair—a mythical archery contest that involves a startling use of sound effects and video animation. This dramatic conceit could never work in a book or in a film, but when performed live and on stage, it seems magical.

The acting is such a unified ensemble performance that one hesitates to single out any one of the excellent cast. Kate Valk collapses on the table, then scurries across stage, playing the Shlump as a combination of Kantor’s tavern floozy, Caliban, and Pierrot. Danusia Trevino, as a character named Water-Hen, contributes a style of acting that seems borrowed from the Polish theater, long before Kantor came along. The fake antique is suggested in certain details of staging and acting, and the pink chair—which has appeared in several Wooster group productions—is there along with it, reminding us of whose play it is, and of the philosophical, procedural, and aesthetic differences between a director who sits on stage, as Kantor did, and one who watches from the audience, as LeCompte does every night.

Throughout the production are melancholy songs and brisk chants, tangos, a Polish hymn, and a Jewish prayer set to music. It ends with the full cast singing “Bound for the Promised Land,” a nineteenth-century cross between an anthem and a hymn, most famously performed by the Mormon Tabernacle Choir. Combining the ferocious, spiritual optimism of the early pioneers, a sly reference to Odysseus and to the restless ghost of Tadeusz Kantor, infused with the anarchic and lyrical sensibility of the Wooster Group, the song is an inspired choice: a simultaneously ironic, heartfelt, and rousing finale.

A PINK CHAIR (In Place of a Fake Antique) will be at REDCAT in Los Angeles from April 5 through 15, and at The Performing Garage in New York City from April 18 through May 19.

Advertisement