In March 2017, John Kelly, then Secretary of Homeland Security, said in an interview with CNN that the Trump administration was considering a national policy to separate parents from their children to deter immigrants from crossing the border into the United States. The proposal triggered a backlash because it was so unpalatable, and the administration didn’t move forward with it. But six months later, in December 2017, The Washington Post and The New York Times reported that the administration was again considering the idea. At the same time, advocates who provide services to children in government custody told ACLU lawyers they were seeing children much younger than the teenagers they usually saw entering their facilities. As the stories began to multiply, the ACLU’s Immigrants’ Rights Project quickly realized that the administration wasn’t considering the separation of children from their parents—it was already doing it.

For at least six months before then Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced the zero-tolerance policy of prosecuting every adult who crossed into the United States without permission, which would result in more than 2,000 children being taken from their parents, the Department of Homeland Security had quietly began taking hundreds of children away from their parents to deter would-be asylum seekers from coming to the United States.

We had no idea how many children had been taken from their parents, but we knew we needed to file a class action lawsuit to stop the practice. To do that, we needed to find the parents. In February 2018, we got a tip that there was a Congolese woman in an immigration detention in San Diego who said that her then six-year-old daughter had been taken from her when she entered the country three months earlier, in November. I lined up an asylum lawyer, a Lingala translator, and flew out to California immediately to meet with her.

Ms. L., as she would be known in court papers, was distraught. Dressed in a detention jumpsuit and gaunt from not eating or sleeping, she was wary at first, though she smiled when I attempted to say hello in Lingala. Through a translator, she explained to the asylum lawyer and me that she feared for her and her daughter’s lives and that the Catholic Church helped them flee. They traveled through ten countries over four months, and requested asylum when they legally presented themselves at a port of entry near San Diego. On their fourth day in custody, immigration officials took her daughter into another room, handcuffed Ms. L. and told her she would be going to an adult detention center in San Diego. S.S., they said, would be going somewhere else. In the adjacent room, Ms. L. heard he daughter scream, “Don’t take me away from my mommy!” That was the last time they would see each other for months, even though Ms. L. had passed her asylum screening interview.

S.S. was flown 2,000 miles away to Chicago and placed in a facility for “unaccompanied” immigrant minors where she would remain for close to five months, celebrating her seventh birthday without her mother or anyone she knew. For days, no one told Ms. L. why her daughter had been taken or where she was. During the nearly five months of their separation, Ms. L. was able to speak to S.S. only a handful of times on the phone, and S.S. cried during each call. We were still a couple of weeks away from having enough information to file a class action lawsuit, but Ms. L.’s situation was urgent. So, a few days later, we filed a suit just for Ms. L. against the Trump administration in US District Court in San Diego, seeking to reunify her with her daughter.

Ms. L. v. ICE would set into motion an extraordinary set of legal proceedings that would expose egregious government conduct, unprecedented in its cruelty and carelessness. It would showcase the importance of a system in which federal judges have lifetime tenure and can look out for the vulnerable notwithstanding political pressure. It would spur demonstrations across the country against the family separation policy, and eventually send the ACLU and a coalition of human rights defenders from other organizations into Central America in search of parents the government had deported without their children. And it would rescue about 2,500 children and reunite them with their parents.

*

At the first hearing in the case, in March, the government argued that it had done nothing wrong. Ms. L. did not have papers showing that S.S. was her daughter, so the government claimed it was acting in the best interest of the child by removing her from Ms. L.’s custody. Ms. L. could have been a smuggler, the government claimed, using the little girl to gain entrance into the United States. It ignored the pair’s striking resemblance to each other, that S.S. was screaming for her mother when Ms. L. was taken away, and the frequency with which migrants have their documents stolen during their journeys.

Advertisement

Judge Dana Sabraw asked the government if it had undertaken any effort to determine parentage in the four months that the mother and daughter had been separated. It had not. He ordered a DNA test, which quickly proved that Ms. L. was S.S.’s mother. With that, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) abruptly released Ms. L. into the parking lot of Otay Mesa detention center with a plastic bag containing her few belongings.

The asylum lawyer that we had found for Ms. L. picked her up and brought her to a hotel. A retired couple from San Marcos, a suburb of San Diego, who had heard Ms. L.’s story on National Public Radio, offered to take her in. The former nurse and her military veteran husband hosted Ms. L. for several days, until we could get her to Chicago, where a shelter for formerly detained immigrants had agreed to house her and her daughter. The mother–daughter reunion that took place a few days later at the shelter was as emotional as anything I’ve seen in twenty-five years of doing this work.

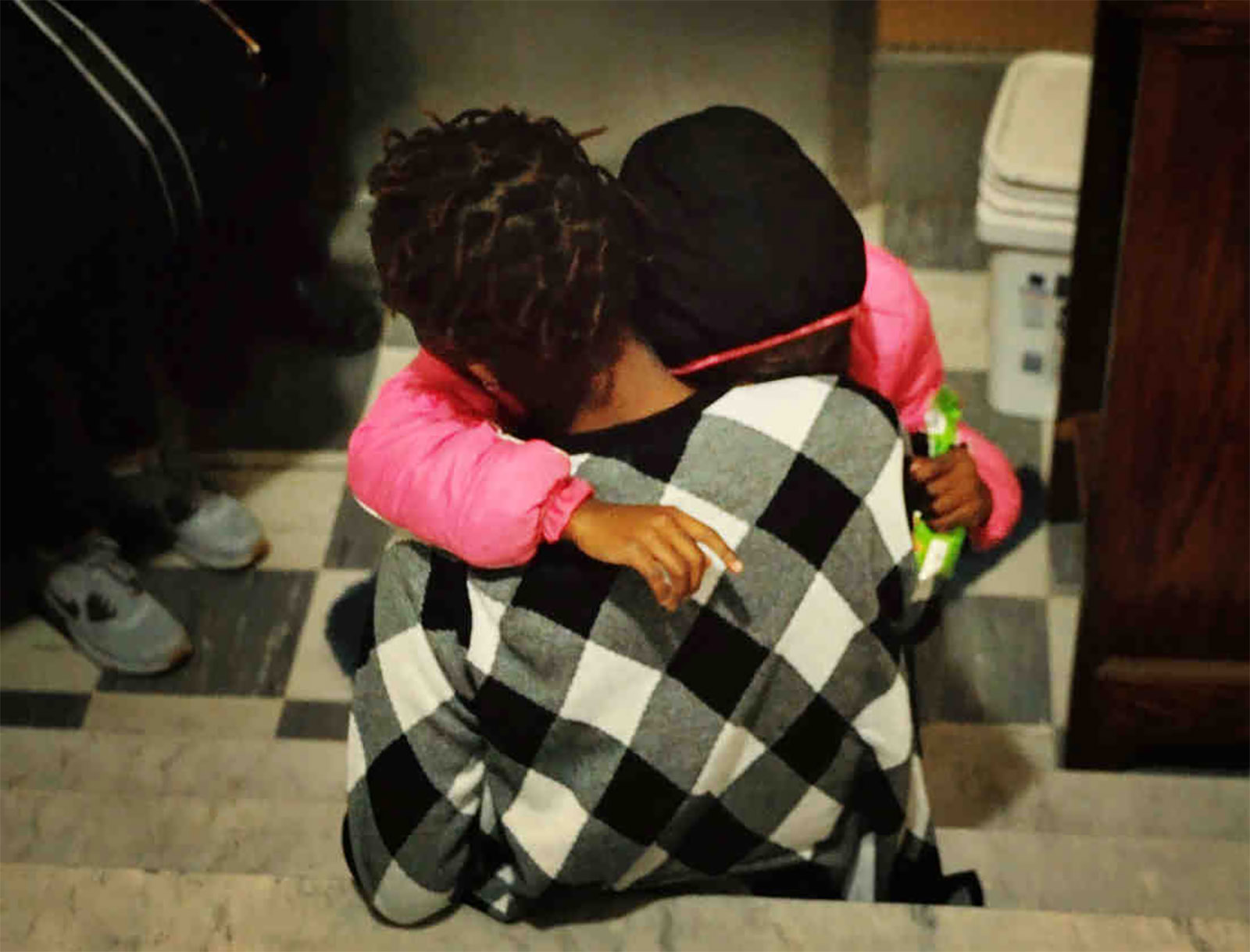

Ms. L., who had barely spoken in the days we were together, sat on the marble staircase just inside the shelter’s front door waiting for the Office of Refugee Resettlement, the government agency in charge of unaccompanied immigrant minors, to deliver her daughter. When the door opened, Ms. L. crouched and opened her arms. S.S., dressed in a hooded pink jacket, toppled into her mother’s arms. For the next minute, they lay there, clinging to one another, rocking side to side, the hallway filled by a low, haunting moan, punctuated by S.S.’s cries.

In the days that followed, the government told Congress that Ms. L.’s prolonged separation from her daughter was a one-off mistake. Lawyers for the government tried to maintain that fiction in court as well, asking Judge Sabraw to dismiss the case, arguing that because Ms. L. and her daughter were now reunited, the issue was resolved. But by that time, we had learned that there were between 400 and 500 children who had been separated from their parents. On March 9, three days after Ms. L.’s release, we expanded the case into a national class action suit and asked the court for a nationwide injunction to stop the ongoing separations and reunite the children who had already been separated. The government sought to have the case thrown out before the judge could even consider the facts, but Judge Sabraw ruled that the case could proceed, stating that a policy of separating children “is brutal, offensive, and fails to comport with traditional notions of fair play and decency” required by the Constitution.

Meanwhile, the reality of what the administration was trying to do was becoming clear. Hundreds more children were being taken from their parents each week, a total that would eventually reach close to 3,000, by the government’s admission. Horror stories started to surface. We learned that even babies less than a year old had been taken away and sent to government facilities. One of our clients described to the court how the government made her strap her eighteen-month-old baby into a government vehicle but would not let her comfort the child when he began crying. Instead, the car drove off while the child stared out the window searching for his mother.

Another of our clients recounted the helplessness she felt when all she could do was tell her little boy to be brave while they dragged him away, despite his pleas to remain with his mother. A father who fled Honduras with his wife and their three-year-old son committed suicide after authorities took his son away. A worker at an immigrant children’s shelter in Arizona quit after he was told to prevent three siblings from hugging one another in the shelter. Parents claimed that Border Patrol agents lied to them, saying they were only taking the children to have a bath, never to return. Lawmakers who tried to visit shelters were turned away. Former First Lady Laura Bush, the United Nations, and the Pope condemned the policy. Seventeen states filed suit against the administration’s policy. And tens of thousands of people took to the streets in protests across the country.

Advertisement

Finally, on June 20, in the face of mounting public pressure and the developing court case, President Trump issued an executive order to stop separating families. But the order said nothing about the families who had already been separated. It also contained dangerous caveats that allowed the government to continue to separate children whenever it unilaterally claimed that separation was in the best interest of the child. Two days later, Judge Sabraw held an emergency hearing. The government’s lawyer acknowledged that the executive order contained no procedure to reunify the children and allowed the government to continue separating families. We urged the judge to grant our request for a national injunction, telling him, “At this point, you are the only one who can really stop the suffering of these little children.”

Six days after Trump’s executive order, Judge Sabraw issued the injunction and ordered the government to reunite all the children with their parents within thirty days, and kids under five within fourteen days. He said the practice of separating families without any procedures in place to track the children or reunify them “shocks the conscience.” As he wrote:

The government readily keeps track of personal property of detainees in criminal and immigration proceedings. Money, important documents, and automobiles, to name a few, are routinely catalogued, stored, tracked and produced upon a detainees’ release, at all levels, state and federal, citizen and alien. Yet, the government has no system in place to keep track of, provide effective communication with, and promptly produce alien children.

By its own account, the government had lost track of approximately forty parents and deported nearly 400 others without their children. For a time, the government even tried to charge the parents for the transportation costs of reuniting them with their children. Some parents were charged not only for their child’s flight, but for the government escort’s fare as well. Remarkably, when Judge Sabraw ordered the government to pay those expenses, the government said that was a “huge ask” and claimed that it did not have a budget for those flights.

When the reunification deadline of July 26 passed, the government had managed to reunite only a little over half of the separated families. And the reunions were chaotic. Some children were even delivered to the wrong immigration detention centers. And there was the matter of the almost 400 parents who had been deported without their children. The government declared it should not be responsible for reuniting those families, and suggested in court documents that it could provide some phone numbers and other information, but that the ACLU should use its “network of law firms, NGOs, volunteers and others” to find the parents. The suggestion that we should be responsible for cleaning up a humanitarian crisis created by the government did not sit well with Judge Sabraw, as he said:

The reality is there are still close to 500 parents that have not been located. Many of these parents were removed from the country without their child. All of this is the result of the government’s separation and then inability and failure to track and reunite. And the reality is that for every parent who is not located, there will be a permanent orphaned child, and that is 100 percent the responsibility of the administration.

Nonetheless, we formed the ACLU steering committee headed by the law firm Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison, and consisting of three other nonprofit partners, the Woman’s Refugee Commission, Kids In Need Of Defense, and Justice in Motion. The government was slow to hand over information it had about the parents who had been deported without their children, but it finally produced a list of phone numbers, the steering committee began dialing phone numbers throughout Central America, sometimes reaching parents who only spoke indigenous languages such as Mam and Q’eqchi’. Members of the steering committee also roamed remote mountainous villages of Guatemala and Honduras in search of the parents.

About 95 percent of the children known to have been separated have now been reunited with their parents (leaving some 130 children still detained far from family members), but the harm inflicted by this policy will emerge over entire lifetimes of the children who are now back with their parents. Many of the children, but especially the very young, are exhibiting signs of mental health problems and trauma, including anxiety and fear that their parents will be taken away again. When I met with one of the original families in the lawsuit after their reunification, the mother told me that her four year-old was still asking her, two months later, whether anyone was going to come in the night and take him away. The medical professionals who assisted us in the lawsuit explained that these children may live with that sense of deep vulnerability for the rest of their lives—something that career officials at the Department of Health and Human Services warned the administration about before the policy was implemented.

Despite the public revulsion over family separation, the attacks against immigrants, and specifically asylum seekers, continue. When relatives of children who were taken from their parents came forward to sponsor the children, some 170 of them were arrested on suspicion of being in the country illegally. The administration has made it enormously difficult for those fleeing domestic abuse and gang violence to obtain asylum. It has also announced that people who cross the border anywhere other than a backlogged port of entry will not be eligible. We have challenged both of these policies in court. Yet the administration is looking to create more family detention centers, which can already hold as many as 3,500 people, so that it can detain asylum-seeking families indefinitely. And perhaps most egregiously, the administration is still separating children from their parents, sometimes using vague and unsubstantiated allegations of wrongdoing or minor violations as justification.

If there are bright spots, one is that the courts have continued to play their historic role of checking the government, sticking up for the powerless and vulnerable. The other is that the American people played an equally vital checking role, making clear during the family separation crisis that there are limits to the cruelty they will allow to be done in their name. The courts and public outcry will undoubtedly be needed in the future, as the administration shows no signs of letting up on its cruel and chaotic attacks on immigrants.

After their ordeal, Ms. L. and her daughter had about the softest landing they could have had under the circumstances. The shelter that took them is run by the Interfaith Community for Detained Immigrants and provides legal services, job training, language instruction and psycho-social counseling. A former convent, it is home to about a dozen other immigrants who were previously held in immigration detention. S.S. is the only child, but she is beloved by the other residents. Ms. L. is taking English classes and sewing lessons and S.S. is attending the ESL program at the local public school. But their future is far from certain. They have a long road of rehabilitation ahead. And they still face the prospect of deportation if their asylum application is rejected.