There’s a moment in William Faulkner’s Light in August (1932) that keeps coming back to me on the hot days of this long hard summer. A passing stranger has found a body in a burning house just outside the imaginary town of Jefferson, Mississippi, the body of a white woman named Joanna Burden, her throat cut, and with the gash so deep that her head is almost off. But that’s not what I go back to: not her murder, nor the murderer’s identity, nor even the fact that she’d spent her life in the town where her “carpet bagger” relatives were killed for trying to get black people the vote. What sticks with me is the first step that the local sheriff takes in running his investigation: “Get me a nigger.” That’s what he tells his deputy, and that last word falls like a blow precisely because the thought is so utterly casual, so inevitable in a world in which its violence comes as a matter of course.

The sheriff doesn’t care which black man his deputy finds. Anyone will do, because he assumes that any black man in the neighborhood will know about the crime, or at least can be made to know. Maybe the murderer was living in that little cabin down back of the house? The man the deputy hauls up claims, at first, to know nothing at all, his voice “a little sullen, quite alert, covertly alert.” He watches the sheriff, wary of a blow, and doesn’t pay attention to the white men standing behind and surrounding him. Then he feels the snap and sear of a leather belt across his back. “I reckon you aint tried hard enough to remember,” the sheriff says, and the belt falls again, its buckle rasping across the victim’s flesh, a physical violence as automatic as that racial epithet itself.

Being black makes that man as liable to attack as if he had committed a crime. It’s dangerous, not telling the sheriff what he wants to know, and yet it might also be dangerous to speak. Two white men have been living in that cabin, bootleggers; or at least two men who look to be white. Should that nameless black man give up their names, should he trust his state’s constituted authorities? Will the police protect him if talking gets him in trouble? Anyone who reads Light in August will understand his caution, knowing as the belt falls that this isn’t an isolated bit of brutality. It’s standard police work in that Jim Crow world, and looking it over again helps this white reader understand the long history behind the deep suspicion of law enforcement that so many Americans feel.

There is a deep congruity between the movements of Faulkner’s mind, with its sense of an inescapable family trauma, and the history and culture of his region, so deep that it hardly seems possible to distinguish between them. So many of the ills he describes are with us still. There’s the voter suppression that sparks the murder of those “carpetbaggers” in Light in August; or his suggestion in The Hamlet (1940) that the black landowners in one rural district have all been driven out, with violence functioning as a primitive form of redlining. He was born into an understanding of the way white supremacy works, and a part of him never stopped believing in the racial hierarchy that shaped his boyhood, even as the writer grew increasingly critical of it.

Time in Faulkner’s world both creeps forward and stands still, like the mule-drawn wagon in the opening scene of Light in August, “moving forever and without progress.” So, in Absalom, Absalom! (1936), the Canadian Shreve McCannon describes his Mississippi-born Harvard roommate, Quentin Compson, as having grown up in a world of “defeated grandfathers,” a world that can’t stop reminding him “to never forget.” Faulkner’s characters can’t put anything behind them, and indeed many of them don’t want to, the white ones anyway. They prefer to live in the moment of loss, as though they were their own ancestors’ ghosts, refusing to let the past become past.

That refusal extends to the built environment as well. Monuments remind us always to remember; memorials that we must not forget. That’s the distinction that Arthur Danto, the art critic for The Nation, made in writing of Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial on the Washington Mall, and by that standard the two statues of Confederate soldiers in Faulkner’s actual hometown of Oxford, Mississippi, seem meant as memorials, too. One of them sits near the entrance to the campus of the University of Mississippi, and a bystander was killed standing next to it during the 1962 riots over the university’s integration. The other is on the town’s courthouse square, a soldier standing with his musket on top of a tall column that you can see as you enter the square from the south. It went up in 1906, and Faulkner’s paternal grandparents were among those who pushed for it.

Advertisement

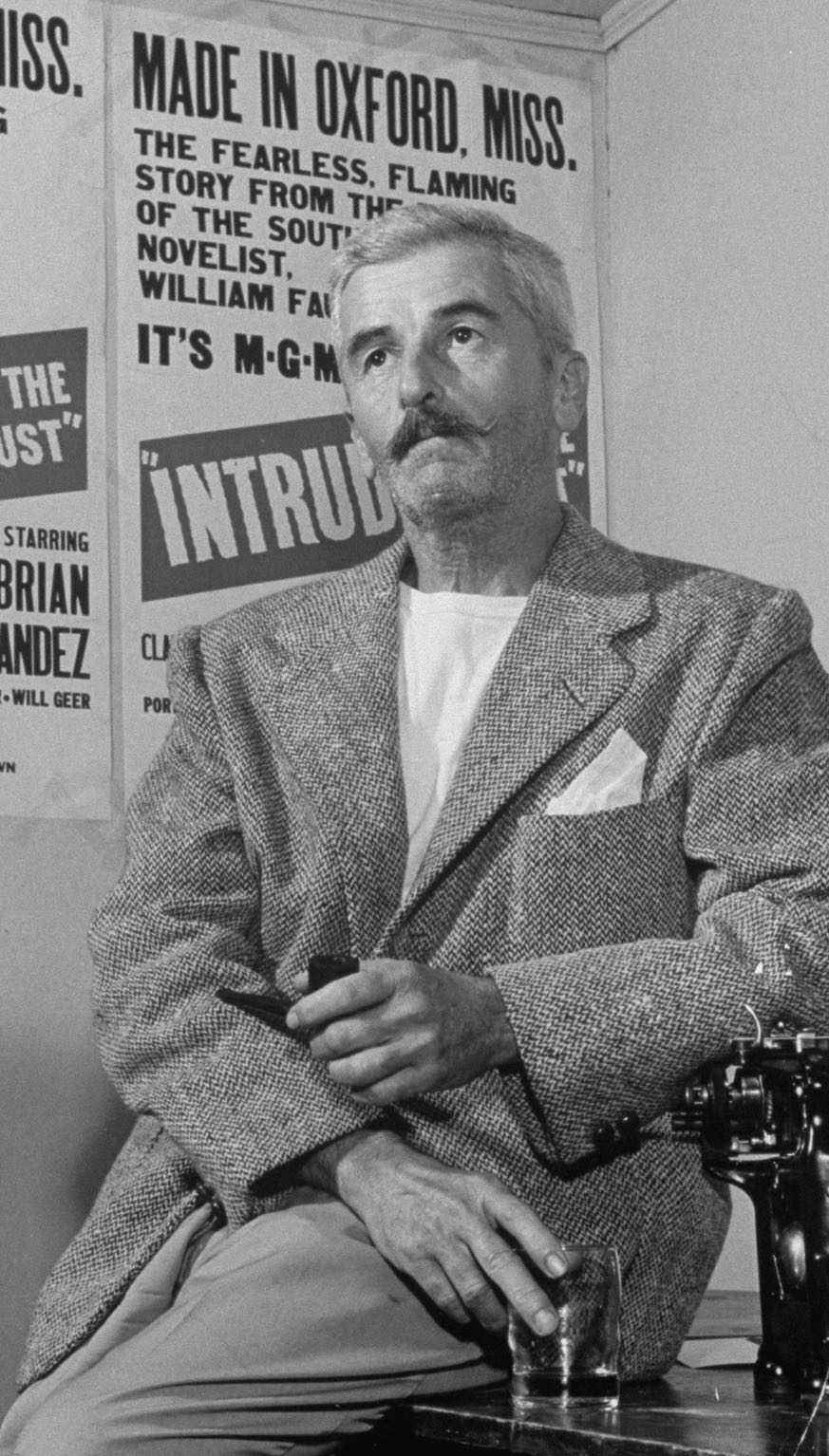

The university has recently yielded to student demands and plans to move its memorial away from that public spot and into a secluded cemetery instead. Oxford’s all-white city council has decided, in contrast, to keep the town’s statue in place, where anyone driving in must look at it, and part of me wonders whether to blame Faulkner himself for that. He didn’t enjoy much local popularity when he was alive, not even after he won the Nobel Prize. He told too many inconvenient truths, and even some of his relatives saw him as writing “dirty books for Yankees.” Yet, by now, he’s a tourist draw. His own statue in bronze sits on a bench in front of city hall, and that Confederate memorial in the square is so persistent a point of reference in his pages as to seem a feature of the natural landscape, rather than the product of human choice. Certainly, it’s what the visitor expects to find: the marble man looming up before the courthouse clock, looking as if he’s always been there and always will.

That statue appears throughout Faulkner’s work, but it plays a special part at the end of The Sound and the Fury (1929). On Easter Sunday, 1928, a black teenager called Luster takes the mentally disabled and nonverbal Benjy Compson for his weekly visit to the cemetery. It’s the first time Luster has been put in charge of the Compson’s horse-drawn buggy, and as he approaches the square, the eyes of the statue upon him, Luster makes a mistake. He takes the carriage to the left of that memorial, hoping to show off to any friends in the square. But Benjy needs routine, he needs repetition. With him, the carriage has always gone to the right, and now he begins to wail, to bellow in “astonishment… horror; shock; agony eyeless, tongueless, just sound.”

Then Luster is thrown from his seat, and a fist crashes down on his head. Benjy’s malignant brother, Jason, has appeared, “jumping across the square and onto the step” of the carriage; he grabs the reins from Luster, threatens to kill him, and then slews the buggy around to the right. Soon enough, Benjy grows quiet, with everything moving once more “in its ordered place” around him. Meanwhile, the marble man stands sentry in the courthouse square over the re-subdued black body. Jason’s fist; the deputy’s belt; the rope that figures in some of Faulkner’s other stories, too. The Sound and the Fury links such Confederate memorials to the legitimized violence of the white society that built them, and, in doing so, stands for me as a monument of another sort, a witness to the injustice of a world from which, as Toni Morrison once said, he would not allow himself to look away.