This article is part of a regular series of conversations with the Review’s contributors; read past ones here and sign up for our email newsletter to get them delivered to your inbox each week.

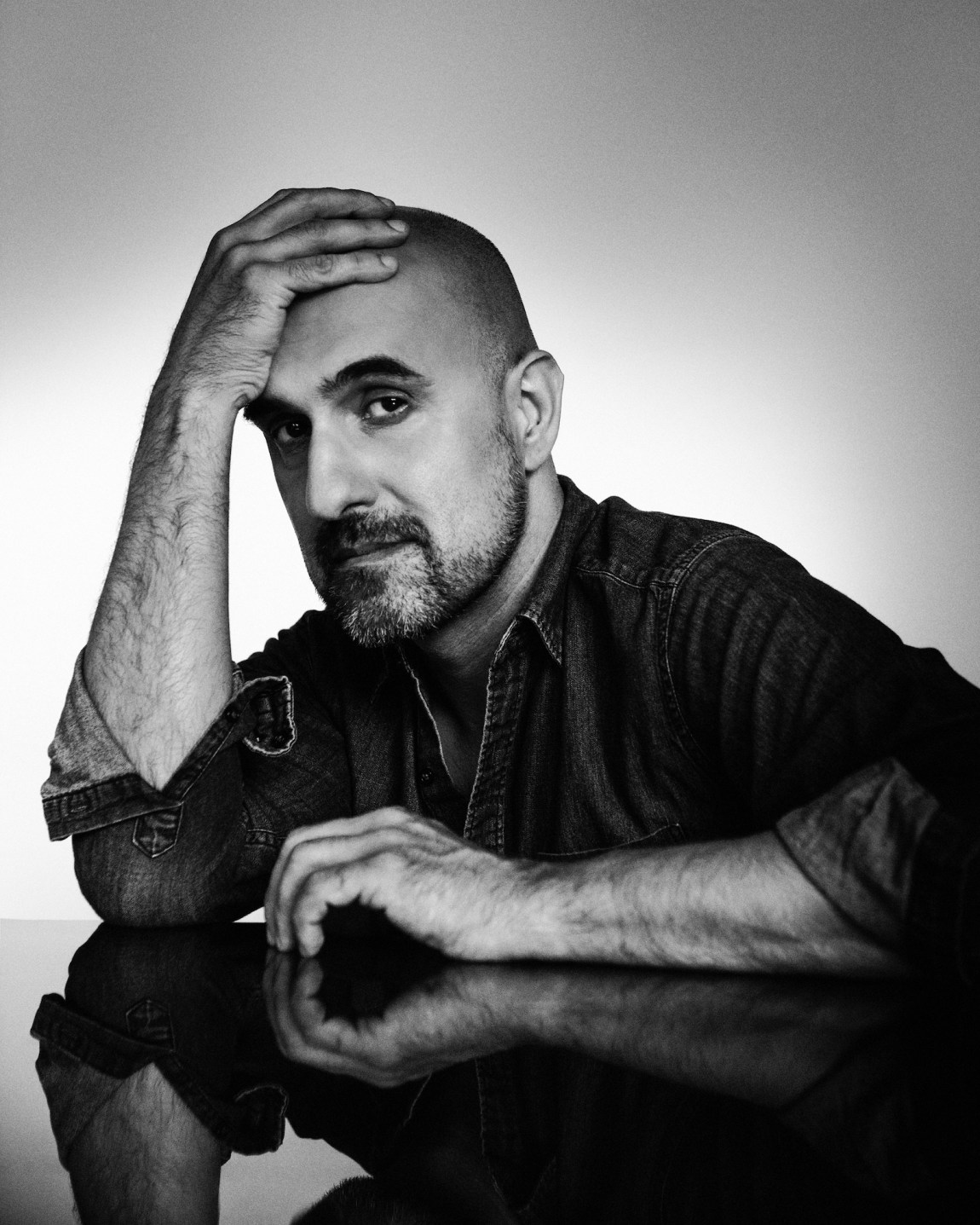

The New York Reivew’s July 1, 2021 issue features “As American as Family Separation,” Hari Kunzru’s review of two books about immigration politics and the detaining of migrant children. Since his first article for the Review, in 2019, Kunzru has become a regular contributor—and one notable for the range of his interests, from autocracy to technology, to race and identity, and nationalism. This reflects a versatility and intellectual curiosity on his part, as an author both of nonfiction—encompassing travel writing, music, tech, and more—and of fiction, with half a dozen novels to his name, including, most recently, Red Pill (2020).

His narrator in that novel, he pointed out when we corresponded recently via e-mail, is a writer who “says that he’s ‘interested in what he’s interested in.’” It’s impossible to be a Baconian polymath in the modern world, Kunzru acknowledges, “but everything does seem to be connected together, and I like to proceed as if I might understand it all one day.”

I was struck by one such connection he made, in his review, between the American right and its obsession with children. This might appear to be merely a cloying sentimentality, but Kunzru sees something far more sinister in it—an extension of white supremacy’s natalism and doctrine of racial purity. He cites a dictum from the Klan leader and neo-Nazi terrorist David Lane in the early 1990s: “We must secure the existence of our people and a future for white children.” This, in turn, reminded me of the fantasy at the heart of the QAnon conspiracy theory, that deep state and Democratic elites are involved in child sex-trafficking—Was this also related?

“Childhood innocence carries a powerful political potential,” said Kunzru. “The impulse to protect the innocent feels morally unquestionable, and if it’s yoked to some other project, whether that’s freeing slaves or storming a dungeon under a pizza restaurant, it can rouse people to action…. It’s not about any children in particular. It’s this hit, this clarifying experience of salvific agency.”

The paranoia underlying convictions such as the one that the Clintons were running a child abuse ring is something that, thanks largely to Richard Hofstadter, we think of as chiefly the style of the American right. But in Red Pill, Kunzru seems to be suggesting it’s more pervasive—a cast of mind that can ensnare and consume any of us. Is this, in fact, now a general malaise?

I think we’re living through a moment when the inhuman scale and complexity of the world has been made visible to us. We are uncomfortably aware of all the things that we don’t know, and we are reacting in human ways. Paranoia is understandable, even logical. Conspiracy theories promise an artificial simplification of these vast, unknowable forces. If there are just a few gray men in a Davos boardroom pulling the levers, then the world is potentially knowable. It’s hard, but necessary, to give up that hope.

Kunzru’s nonfiction writing is, as he says, “analytical, and sometimes polemical”—and that drive for assertive, declarative understanding is very visible in his current review. It’s also more or less the mission of his new podcast, Into the Zone (published under the umbrella of Jacob Weisberg’s Pushkin Industries), which might be described as a series of intellectual quests. Yet that seems almost at odds with the sense in his fiction that knowledge might be radically unreliable, even dangerous—built on connections that could be wrong, or mad.

“Fiction thrives on moral complexity and ambiguity,” he said. “Often, in fiction, I’m trying to stage situations or conversations without imposing a particular conclusion. It’s interesting to let characters talk, particularly characters that I don’t like or agree with.”

Kunzru is married to another fiction writer, Katie Kitamura (her latest novel, Intimacies, is due out in July). I’m always nosily curious about how two-author households manage that literary dimension of intimacy.

[She] is my first and best reader, and I try to be that for her. We don’t show each other our work in progress or discuss it in detail until we have complete drafts, so that we can give each other a “clean” read. It’s a terrible mistake for a writer to use a partner for emotional support. If you just want to be told “it’s great, carry on,” you don’t actually want their opinion. Katie knows what I’m trying to do in fiction, so her notes are incredibly valuable.

Kitamura is Japanese-American, while Kunzru is British (his father was Indian). Living in New York City makes sense, he said, for a family with a complex history of migration—“It seems like the right place for us, a place where we don’t have to apologize for ourselves.” For all that, Kunzru professes to be “culturally very English,” in a way that refutes any facile assumption of his being a rootless cosmopolitan. “I am very happy hiking to a stone circle,” he said, “or photographing inscriptions in a country churchyard.”

Advertisement

Somehow, those two particular examples made a connection for me with another abiding interest of Kunzru’s: ufology. Thanks to a recent declassification of documents by the US government, the idea of such unexplained phenomena and possible extraterrestrial visitation has migrated from the crank fringe to the front page of The Times. How does he read all this?

There’s a UFO eschatology, which is essentially just a sort of high-tech Christian spiritualism. I find that culturally interesting but, let’s say, not particularly useful as a way of understanding anything. I’m excited by the recent disclosures, because they really do seem to represent something new, as does the relaxation of the military taboo on admitting that UFOs exist. For the first time we have, in the public domain, authenticated images of UFOs. That’s a huge shift in the terrain of this conversation.

There’s nothing to say that these objects are extraterrestrial. We can say that they seem technological, that they don’t behave like aircraft that we are familiar with, and that the US government is denying that they are American. That’s it, so far….

Where does that leave us? Probably some way short of having to take a position on whether to join the intergalactic federation.