Watching glamorous industry awards shows usually involves the hope of witnessing some contagious human happiness, but it is also a glimpse into the business world of the performing arts. This past March, watching the Grammys in quarantine was a puzzle for many who were watching solo, and afterward I received several phone calls from people attesting to a state of bewilderment. “I hate to sound like Betsy DeVos,” said one friend, “but what was that Cardi B/Megan Thee Stallion sex-miming thing?”

Was it a cynical thing done for money, as too many things are?

“It’s not for us,” I said, uncertainly. “It’s for young people. I think.”

The thing that was for us, the thing that was for everyone, it seemed, was Bruno Mars and Anderson .Paak. (Although when something is for everyone, it may be dismissed as “poly-demographic entertainment”—that is, a cynical thing done for money.) Mars and .Paak were calling themselves “Silk Sonic,” and they put on the best show of the night, with hilarious but handsome early 1970s dress suits, Motown-style choreography, and a hip-hop-inflected, slow-jam ballad titled “Leave the Door Open,” sung with humor, call-and-response, key changes, blasted-out passion, and two back-up vocalists. Mars had excised the booty-call aspect from the studio version and sang as if his heart were about to break, belting out the bridge and taking the final chorus up high, past the initial recording’s octaves (Mars’s live versions are always better than his studio ones, which are also ill-served by their promotional videos). This was not a Michael Jackson falsetto but a bleeding, pleading chest voice. He sounded like a cross between Frank Sinatra and Gladys Knight. Wow, Bruno Mars has become a great singer, I thought. He must have quit smoking.

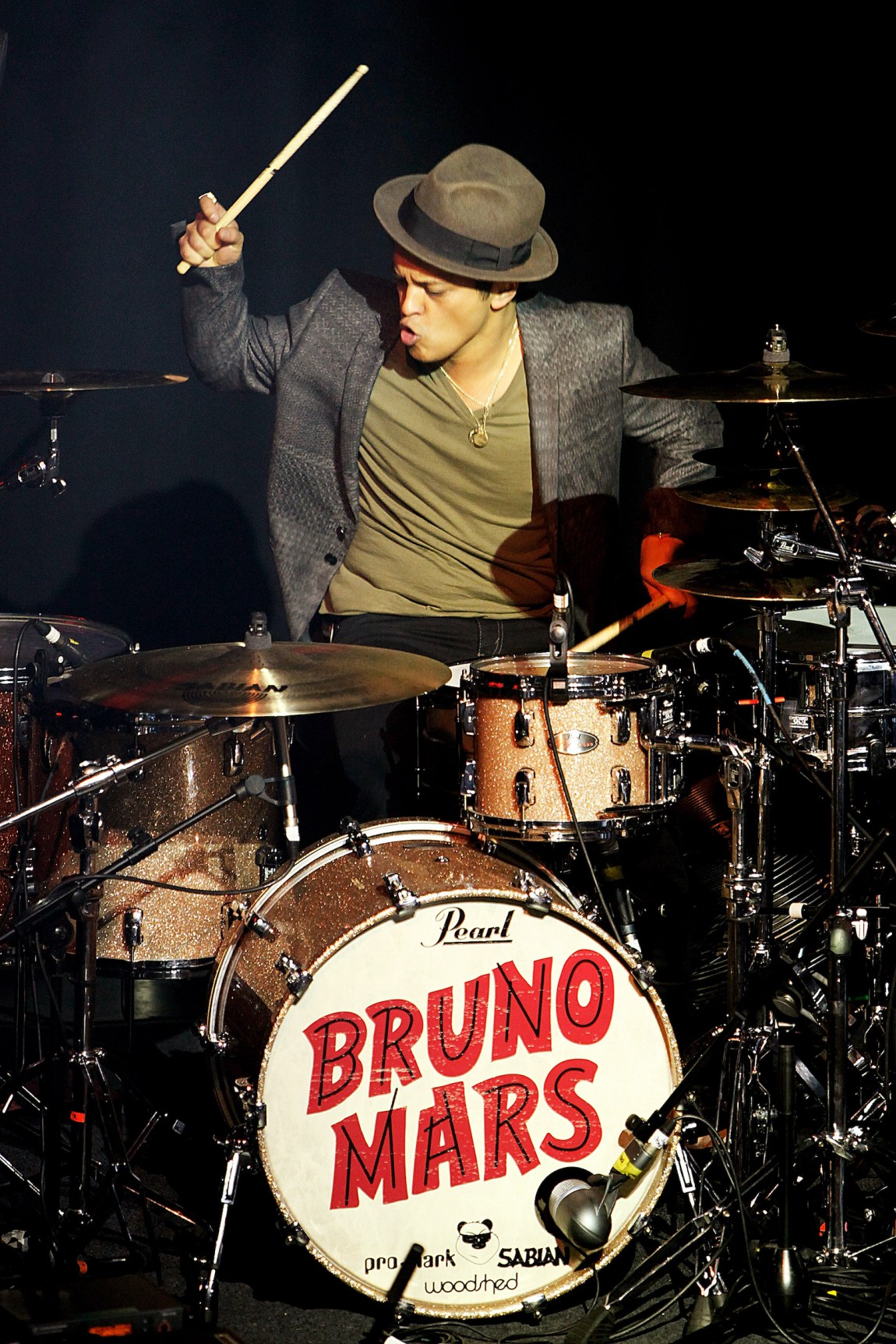

There is a bit of Astaire and Rogers to Mars and .Paak. Not that anyone is dancing backward in heels (for that, there is Mars and Beyoncé with their respective squads in a thrilling dance-off at the 2016 Super Bowl halftime show; Beyoncé, in terrifying shoes, almost takes a spill, but the only better dance-off is Rita Moreno and George Chakiris with their rooftop squads in the 1961 film version of West Side Story). Mars and .Paak are not only both of part Asian heritage—this fact has significance for, among others, young Asian-Americans who don’t see a large Asian presence in American pop music—but they also each give the other something he needs. .Paak, a rapper, has hitched his wagon to a determined hitmaker. But he also keeps Mars from going too retro and lends him some street hipness. Both, early in their careers, were broke and briefly homeless. Both remained emotionally close to their Asian mothers. Both are drummers: .Paak has played drums and sung on NPR’s Tiny Desk concert series (intimate, personal, niche); Mars has played drums and sung at the Super Bowl (a show!).

Mars, a producer, a businessman, a musical technician, is often considered by others to be a charismatic impersonator of others—Elvis Presley, James Brown, Prince, Michael Jackson, Teddy Pendergrass. He is a talented showman who, without a conventional dancer’s body, can still move with precision and immaculate ease (his mother was a dancer; his father a struggling doo-wop bandleader). One gets the feeling—especially when talking to musicians—that Mars is not always respected as an artist the way .Paak is, but is perceived instead as an assembler of commercial dance songs, a skilled entertainer, and so remains in a quietly demoted condition, prestige-wise. Under which he must bear up, even if it is all the way to the bank.

But this misses the real strengths in Mars’s work. To those who would criticize it for being “pastiche,” one might ask what art form in this century does not blur traditions, glue and fuse and mash and quote and echo and add, subtract, and sample. Thou shall not steal. But real artists steal, said both T. S. Eliot and Picasso, and both would know. Where successful appropriation is concerned, Shakespeare is the most brilliant example. One cannot assemble anything in a vacuum. Is a salad disposable and unoriginal because one can recognize the vegetables and discern the soil in which the greens were grown? How could a musical artist who is part Puerto Rican, part Ashkenazi Jewish, part Filipino, and who grew up in Hawaii, be working in a single musical idiom? Such a path scarcely exists in America now, and arguably never did.

“I wear my influences on my sleeve,” Mars has said in interviews. In this, he is somewhat akin to Amy Winehouse or even to Bob Dylan. He trusts the sources, the springs, and the wells. He assembles drafts of recombinant sound. Sometimes, the results are exciting: he finds a strong emotion and places it in a structure where it can live, and where others can visit and experience it. He works the math of a composition. Nothing is done quickly. “All I Ask,” written with Adele and a touch of Rachmaninoff, was composed to be calculatedly “soppy” (Adele’s word); it is also a genuine tearjerker. Once in a while, there is a song such as “Locked Out of Heaven,” the lead single from Mars’s second studio album, Unorthodox Jukebox (2012), that seems to borrow explicitly, rather than implicitly, from elsewhere—in this case, Sting’s 1979 “Message in a Bottle.” When asked about the resemblance, Sting, often a gentleman, claimed he didn’t hear it that way at all.

Advertisement

Mars’s detractors sometimes go so far as to suggest he is performing in blackface (like the jazz-infused Joni Mitchell on Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter or Mingus?). But music doesn’t work that way. If music required a 23andMe test everyone would fail—or everyone would pass. Culture is cultural exchange. And American music is African-American music. As Mars himself has said. Would we want an artist who can put elements together in an interesting way or a hypothetical naif?

Mars, like most musicians, has open admiration for a great variety of people and has his own favorite songs. “I wish I could write Marvin Gaye’s ‘What’s Going On?’ or Michael Jackson’s ‘Man in the Mirror,’” Mars has said. “But I can’t.” Nonetheless, he has sometimes employed a plaintive, tender descant reminiscent of both those singers. And as for many Black musicians not having received their due, few people would argue. But Mars’s attachment to R&B is an act of love, time travel, conservation, inclusion, and skilled fusion. He is mixed race. His band is Black. It’s the twenty-first century.

Pop music can be, somewhat counterintuitively, the place a listener goes with their own private uncoolness. There are singers and songs one embraces that one cannot really explain to friends: earworms and heartworms of hope, yearning, incipient joy, unaccepted loss, desire, and the getting and losing of love. All that notwithstanding, Mars has three or four songs that go deeper than his songwriting is often given credit for: they contain pain and a subtle social commentary, but the lyrics are tightly brocaded, and there is a tapestry of synthesized sounds conveying them, plus a strong beat—for ease of entry to the listener’s head.

“Uptown Funk” (2014) seems to embody some essence of Mars—Julio, who gets the stretch, is summoned again for scampi in Mars’s subsequent lifestyle-anxious “That’s What I Like” (2016)—and it’s the song with which he’s most associated. But “Uptown Funk” was largely composed by the British songwriter Mark Ronson, and is so heavily influenced by other artists that it is one of the most litigated titles in American pop music; Ronson and Mars share songwriting credit and royalties with an array of former plaintiffs.

Mars’s “24K Magic,” released two years after “Uptown Funk,” without Ronson, has been thought to be a similar kind of homage song—they are both rallying, preening funk anthems intended to get one’s damaged masculine spirits up and about—oh, and here are some neo–Jerome Robbins movements to go with them. But “24K Magic” is more complex: its lyrics are an intricate basket weave. “We too fresh/Got to blame it on Jesus/Hashtag blessed….” It’s about bucking oneself up to enter a room. It consists of instructive self-talk and makeshift swagger to help one through a door, from an unlucky room to a lucky one. Or in its opulence at least, a fantasy one.

“Guess who’s back again?” announces the singer from the swirl of his own mind. He is bringing some wannabe players along who are advised to be strong and not look economically insecure. He’s a fast-talker along the lines of The Music Man’s Robert Preston, an early rapper. (“Certainly mighty proud I say/I’m always mighty proud to say it.”) Wearing “Inglewood’s finest shoes” with a pimp’s bravado, he will move on through the gathering. “Why you mad? Fix ya face, ain’t my fault y’all be jocking.”

It is about tenuous hope displayed with an untrembling smile. Don’t cross your fingers superstitiously: “Put your pinky rings up to the moon.” The societal pain and scarring poverty registered in the work of Kendrick Lamar are the prequel and subtext to the evanescent evening of self-worth rituals put out there on planet Mars.

Given the elusiveness of happiness and the accumulation of bad times, Mars charitably positions several of his songs in the doorway of a party. For a feeling of safety, a desired woman may require a man to have some visible money, the lyrics suggest. And thus “24K Magic” almost parodically embraces the impoverished boy’s fantasy of emotional and material success—and excess: the culture’s capitalist craze for the flimsy accoutrements of fun, affluence, leisure. Only when Mars “break[s] it down,” as he calls it—that is, pauses the song to depart from it slightly—do we feel pieces of warped reality: the party goes on tilt and blur, and loses its joy. Can the wobbly promise of redemption deliver? The song simply stops. The fantasy has evaporated.

Advertisement

“Versace on the Floor,” a slow-jam ballad on the 24K Magic album, is not just product placement or displacement: it’s the lover saying, You don’t need this social-class armor anymore. If you were ever really wearing it to begin with. In his exuberant 2017 concert at the Apollo Theater, Mars, in what looks like a Hawaiian shirt, performs this song with unusual emotion, giving it some Broadway and some jazz, a different kind of uptown funk. (When they step ashore, Hawaiians—see Bette Midler, Barack Obama—appear to arrive in the upper forty-eight with great energy and ambition.)

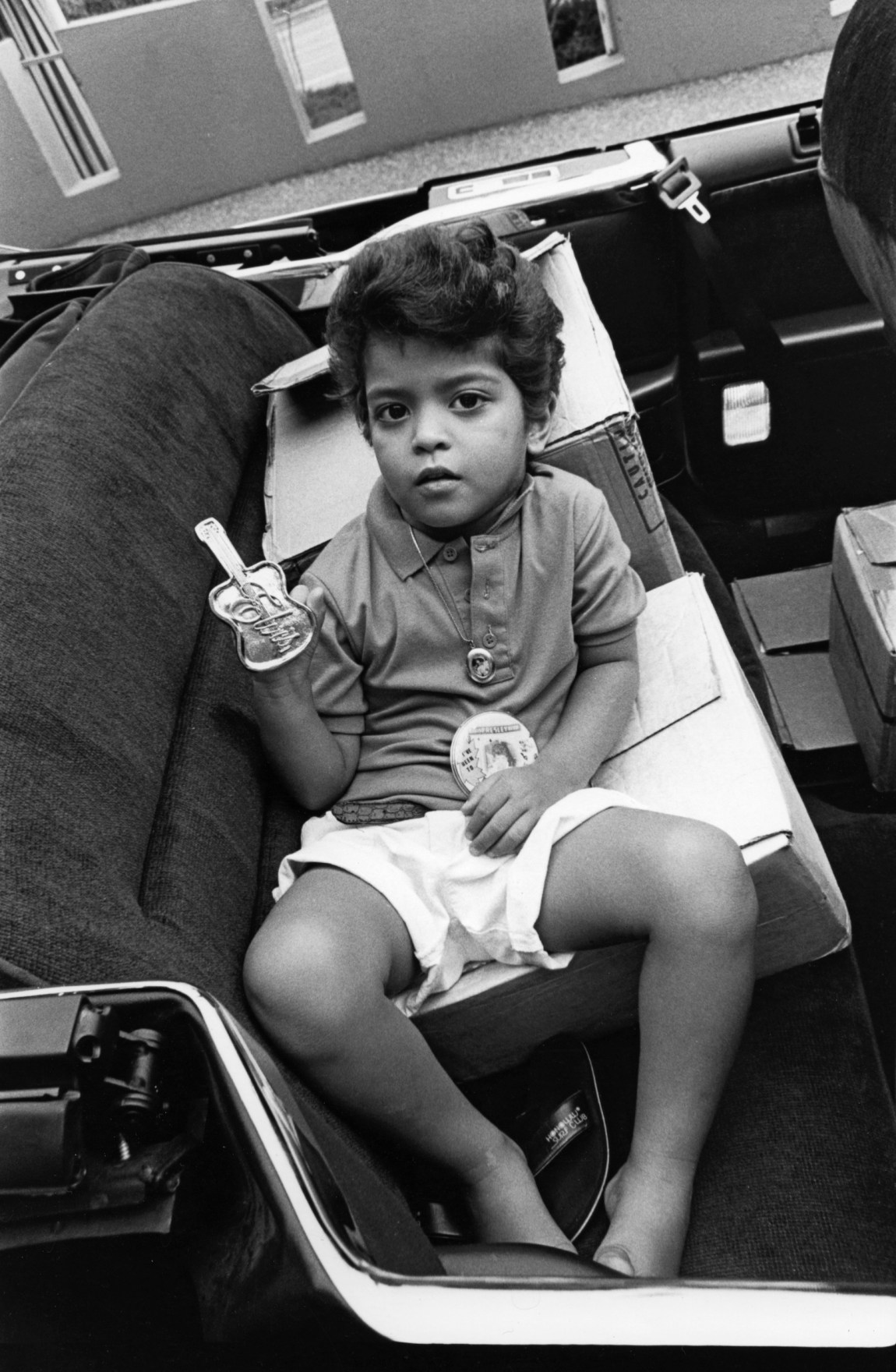

A short, poor kid who was bullied but sang in the high school chorus and then was kicked out for trying to teach his choir mates Jimi Hendrix’s “Fire,” Mars lived as Peter Hernandez for the first part of his life, mostly in poverty in Waikiki, Hawaii, and briefly on the streets of Los Angeles. But he has been in show business a long time. When he was less than four years old, his parents sent him out into the world as a tiny Elvis impersonator, and the footage of this is a little heartbreaking. Later, he worked as a Michael Jackson impersonator, cultivating a sound he hasn’t always shaken loose from his voice and a dance style he doesn’t always bother to avoid, though Jackson, the superior dancer, can look gaunt and ghoulish compared with Mars’s athletic bounce.

Mars’s career has been both predictable and not. He was signed early on by Motown then dropped. Would he go back home and sing Polynesian tunes in hotel lounges? Atlantic picked him up and just this year bought a good portion of his catalog. In a 2010 video, a virtually unknown Mars sweetly strummed acoustic guitar with rapper Travie McCoy singing “I Wanna Be a Billionaire,” sitting on an empty loading dock in the Los Angeles sun, as if daydreaming an impossible future. In 2014, on The Voice, he was fronting his excellent band, The Hooligans, grinning and wearing curlers in his hair. (Mars is full of magnetic and boyish innocence, which he has never lost and which the joyless Jackson never really had, not even as a boy.)

In Mars’s best songs, such as “24K Magic,” one can hear the late-twentieth-century collection of intricately laid licks, hooks, and tracks stacked and repeated. “I’m a dangerous man with some money in my pocket/Keep up!”But musicians have always composed and collected musical phrases in this manner. Both Stephen Stills and Prince kept them locked in safes for future use. There is always the threat of theft. Even sticky-fingered Brahms had no qualms (steal this rhyme anytime). Moreover, the aptly named Rolling Stones album Sticky Fingers features among other highly influenced songs the exquisite “Wild Horses,” Keith Richards’s much-disputed collaboration with Gram Parsons, for which Parsons received no credit whatsoever.

As for Mars’s most recent hit, the one with Anderson .Paak, again there is a door—a passageway from one place to another: I’m a leave the door open. I lost my mind a little bit during quarantine and tried to find narrative writing lessons for my students in the transcendent Grammy performance of this song: See how Mars winds himself up for the cry of the final chorus; he exits the group choreography, then spins and lunges, zigs and zags, using physical movement to power his vocals. Action creates speech and vice versa. Inner and outer are in a dynamic exchange.

Well, it was a long, lonely semester. Put your pinky rings up to the moon.