This article is part of a regular series of conversations with the Review’s contributors; read past ones here and sign up for our email newsletter to get them delivered to your inbox each week.

Since 1963, the inaugural year of the New York Review’s publication, Neal Ascherson has been one of its most prolific contributors. It was nearly three decades before there was a year in which he did not contribute at least one article, sometimes three or four. The most recent, in the December 2, 2021, issue, is “Grand Illusion,” a review of The Confidence Men by Margalit Fox.

At one level, this gives occasion for Ascherson to tell a ripping yarn about how two British POWs in World War I hoodwinked their Turkish captors into permitting their escape; and for this attempt all they needed was not a wirecutter or a shovel, only a Ouija board. But, as ever with Ascherson, you never get mere history, and here he reflects deeply on the techniques of “coercive persuasion” in ways that illuminate our own “age of lies.”

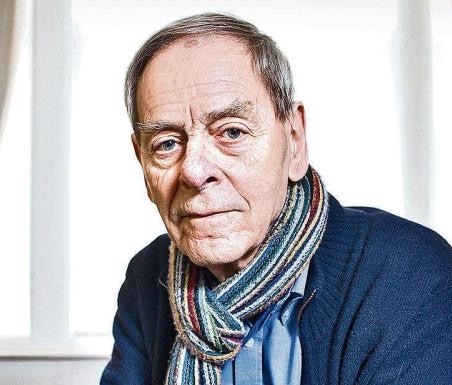

The Scottish-born writer, a journalist at The Observer for thirty years and the author of numerous books, possesses a polymathic breadth of interests and expertise. His work for the Review alone has encompassed everything from history and politics to biography and fiction. Even his reviews of novels—a list that includes work by Chinua Achebe, Nadine Gordimer, Czesław Miłosz, Günter Grass, Nuruddin Farah, Wole Soyinka, Rose Tremain, Hanif Kureishi, Martin Amis, and Ian McEwan—span continents and generations. My first questions to him, in our recent correspondence, were aimed at gaining a better sense of what had fed his capacious curiosity and ranging intellect.

“I’m a cultural mongrel, because almost all my education was in England,” he explained. “But growing up in wartime Greenock taught me the resilience and solidarity of Scotland’s old industrial working class. The depopulated Highland landscape told me what the strong will always do to the weak, if they are not controlled. Scottish Calvinism taught me determinism, the element of delusion in free will.”

A scholarship took him to Eton, where he first encountered “England’s ruling caste, with its calm sense of entitlement and privilege.” He saw enough of it to resolve “never to be part of that”—though a consciousness of its “unnerving” historical continuity in English society would be hard to avoid. “Years later,” he told me, “I went to a show of Holbein’s portraits of Henry VIII’s court. I recognized so many faces, even names. I had been at school with them.”

Ascherson gained a place at Cambridge but opted to do his National Service beforehand, in 1951–1952. That turned out to involve a lot more than polishing regimental brass in some sleepy outpost: he served as an officer in the Royal Marines in Malaya, where colonial Britain was busy suppressing a Communist insurgency. It proved a formative experience:

The so-called Malayan Emergency was a very small war, an inoculation against the real thing. War’s elements were there—bloodshed, destruction, eviction, fear, lies, atrocity—but in tiny, immunizing doses. I learned that I could kill and feel triumphant, not guilty. I learned that the British Empire rested on colossal unfairnesses and that it could transform decent white men and women who entered it into puffed-up petty tyrants. It became obvious to me that even if the Communist insurgents were not the “right side,” I was on the wrong side.

Appropriately enough, when Ascherson did reach Cambridge, the Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm became his tutor at King’s College, and later a friend. “But he never pushed his communism on me,” said Ascherson. “I remained a Marxisant nonparty person, much involved in national independence struggles in Africa (I was briefly propaganda secretary of the Uganda National Congress).” After graduating, he went to work first for The Manchester Guardian (as it still was), then The Scotsman, before settling at David Astor’s Observer. It became a long-term home:

I felt fiercely loyal to the paper’s triple agenda in the 1960s: détente between East and West in the cold war, French-style “planification” for economy and society, and independence for the colonial empire. But I knew myself to be well to the left of the paper’s often maddening liberalism.

The best times were my years as Central Europe correspondent based in Berlin, covering all the Polish dramas between 1956 and 1981, the Prague Spring of 1968 and the tragic Warsaw Pact invasion, spells in apartheid South Africa, Chile after the Pinochet putsch, the Troubles in Northern Ireland. I was enthusiastic for the Paris May in 1968 and for the young revolutionary upheaval in West Germany and Berlin; my Observer editors were puzzled and shocked by my attitude. (Luckily, they never knew that France had then declared me a “prohibited immigrant.”)

In the 1970s, Ascherson also freelanced as a scriptwriter for the monumental ITV documentary series The World at War—its austere newsreel footage of wartime in Europe, Asia, and the Pacific, accompanied by the sober, almost funereal tones of Laurence Olivier’s narration, made a huge impression on my young self and, no doubt, millions like me. “I was taught by men and women who were veteran craft-masters of British film and TV documentary,” Ascherson said. “Their gospel then was that ‘the pictures must tell the story.’ Nearly fifty years on, The World at War is still exciting and educating new generations on every continent. Maybe that was the most important work I ever did.”

Advertisement

His favorite among his own books, he told me, is Black Sea (1995). “It’s not so much a travel book or history as a compound exploring of human imaginations about place and destiny. (Claudio Magris is a pioneer of this approach.) It’s largely about nationalisms, noble or depraved.” His interest in nationalisms owes something to his mixing with “New Left people,” as he noted:

I was completely converted to Tom Nairn’s and Perry Anderson’s diagnosis of the Anglo-British state: still backward because of a failed “bourgeois revolution” in 1688, which had merely replaced royal absolutism with parliamentary absolutism. This in turn reinforced my belief that Scotland should regain independence (something I have dreamed of since childhood), leading to the breakup of the UK and the emergence of a modern, left-wing, constitutional republic in Scotland.

In that, at least, Ascherson seems close to seeing his lifelong wish fulfilled. Elsewhere, he said, it is a baleful prospect in view:

Back in the 1980s, my worst dream would have been to wake up in a world like this. The end of the cold war led also to a withering of democratic socialism. The neoliberal “end of history” years reversed the long trend toward equality, dethroned the primacy of the public interest, and generated resentful majorities lacking job or social security: the new “precariat.” The social-democratic parties, which once represented such people, had moved far to the free enterprise right, leaving a political vacuum that angry populist-nationalist movements soon occupied. This is an unjust and unstable structure, which will fall over. But who will kick it down?

Still, in the face of all this, he told me, he would call himself a “radical social democrat.” He credits this stance partly to Tony Judt (whose magnum opus, Postwar, Ascherson reviewed for the LRB): “I was very moved by [his] opinion that the three postwar decades in Western Europe—granting its peoples a generation of social security, increasing equality in a shared prosperity, and maintaining unbroken peace—remain one of the human race’s proudest achievements.”

One of Ascherson’s notable though perhaps lesser-known achievements is his work in a field of study known as “public archaeology.” He founded and edited a journal of that name and has been a lifelong member of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland (which made him an honorary fellow in 2011). I was intrigued but ignorant. He had to explain to me that public archaeology has a very different meaning in the UK from its American usage—which simply refers to archaeological work done on federal lands—and originated with a professor at London’s Institute of Archaeology, Peter Ucko:

Public Archaeology means, in Britain, all those areas in which archaeology intersects with the “real world.” It can include planning laws, the illegal antiquities trade, the metal-detector clubs, the “right to heritage,” the handling of archaeology in the media, fiction or national propaganda, or the history of the profession itself. As a subversive doctrine, it proposes that archaeology is about Now, rather than Then, that it is about the living rather than the dead, that it is not impartial but highly political.

As Ascherson enters his ninetieth year of life, and his seventh decade as a contributor to the Review, that seemed a just and well-earned note to end on.