This article is part of a regular series of conversations with the Review’s contributors; read past ones here and sign up for our email newsletter to get them delivered to your inbox each week.

Claire Jarvis’s review of Rachel Cusk’s latest book, Second Place, in our February 24, 2022, issue, is accompanied by a portrait of Cusk by graphic novelist and illustrator Adrian Tomine. I have been reading Tomine’s comic series, Optic Nerve, since the early 1990s, when he put out his first issue while still in high school. Tomine lives in Brooklyn, but he was born in Sacramento, and northern California is the setting for many of his stories. His drawings are evocative and efficient, and his storytelling levitates alongside them, spare, never directing the action any more than necessary. My favorite examples of his work leave a measure of white space—as in the Cusk portrait of the writer at an overcast shoreline—for readers to move around in and feel the passage of time.

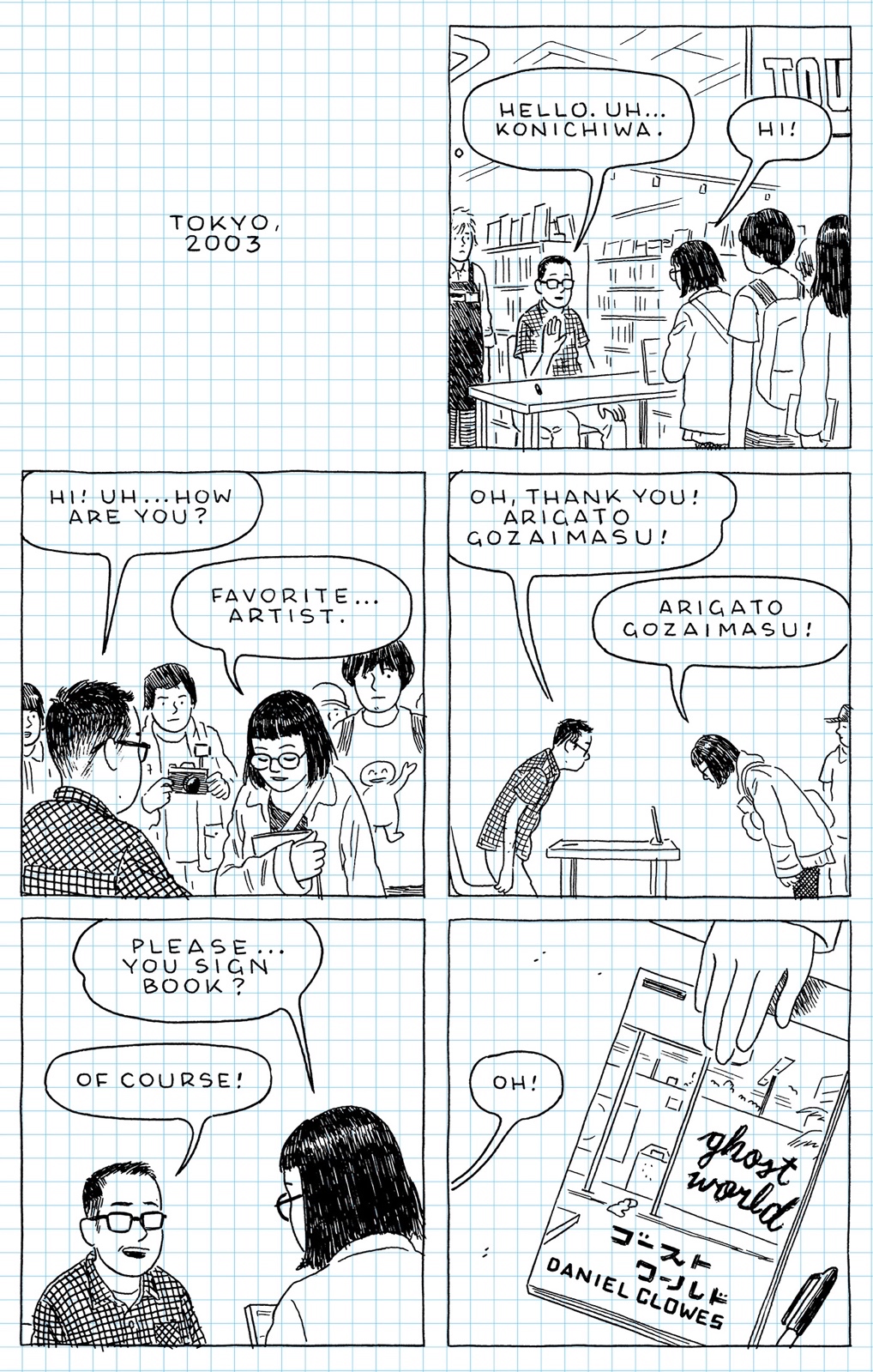

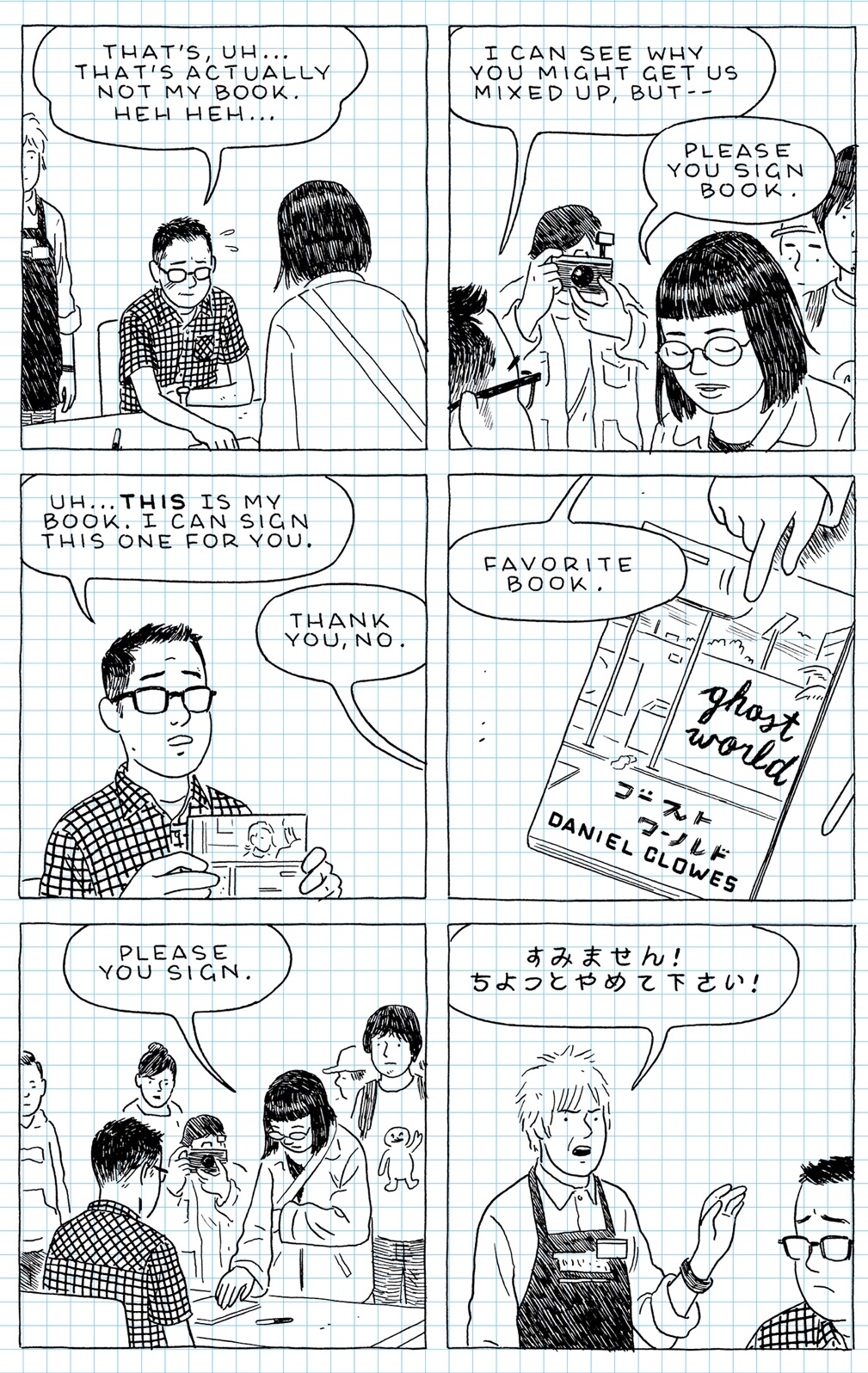

Tomine’s most recent collection of stories, Killing and Dying (2015), has been translated into eleven languages, and his graphic memoir, The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist (2020), is being adapted for television. Tomine and I e-mailed back and forth this week about looking at people and reading screenplays.

Leanne Shapton: How do you feel about illustrating portraits or doing likenesses? I’ve seen you draw perfect strangers at book signings, and it’s a delight to behold. Were you always good at that?

Adrian Tomine: Likenesses were not something I ever thought I was particularly good at, but the requests keep coming, so I try my best. I’m in awe of people who have a natural gift for likenesses, even if it’s some guy doing sketches of tourists in Times Square or whatever. I think it helps to have a more exaggerated, almost grotesque style, but that’s not really what people hire me for. I guess I do a good job of making real people look like characters in one of my comics.

In her essay “Joy” (NYR, January 10, 2013) Zadie Smith wrote about the joy she felt looking at people’s faces. Along with eating, her “other source of daily pleasure is…‘other people’s faces.’ A red-headed girl, with a marvelous large nose she probably hates, and green eyes and that sun-shy complexion composed more of freckles than skin.” What is it you look at in faces, or figures, or bodies? What affects you? You’re so good with posture and conveying mood through body language.

I’ve always been more of an observer than a participant, and as strange as it might sound, I sometimes feel a deep connection with someone through the process of drawing their portrait. If I’m drawing someone I know in real life, I can often remember how they stand or how they hold their head, and then I try to get that down on paper. And if I’m drawing someone I’ve never met, as in the case of this portrait of Rachel Cusk, I spend a lot of time studying photos, and I try to compile as many little details as possible. I don’t know if all this work has any effect on the casual viewer, but it definitely brings the drawing to life for me, and I like to think that the subject might have a brief thought like, Oh, that’s that coat of mine or Yeah, that’s how I hold my hands.

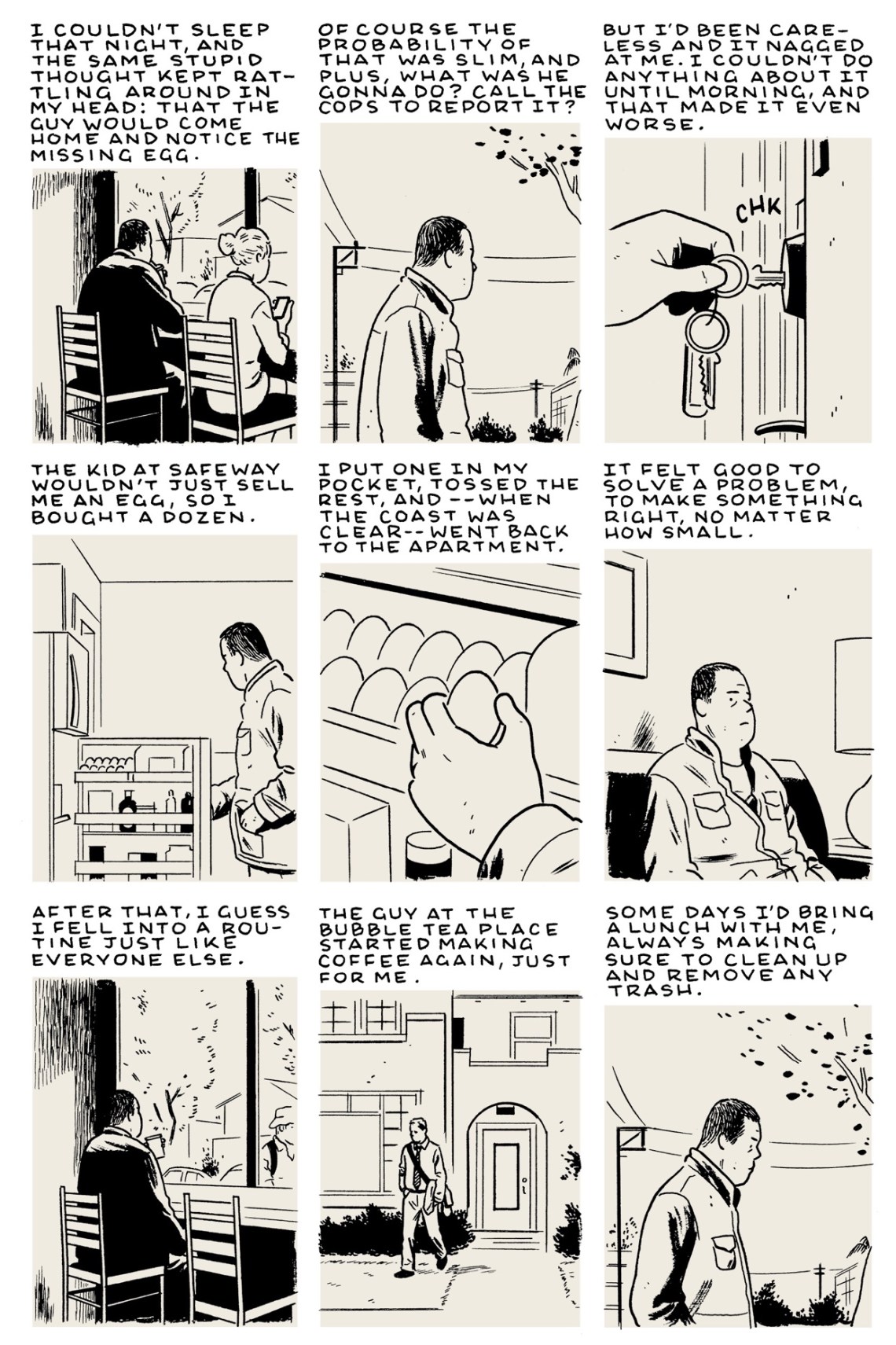

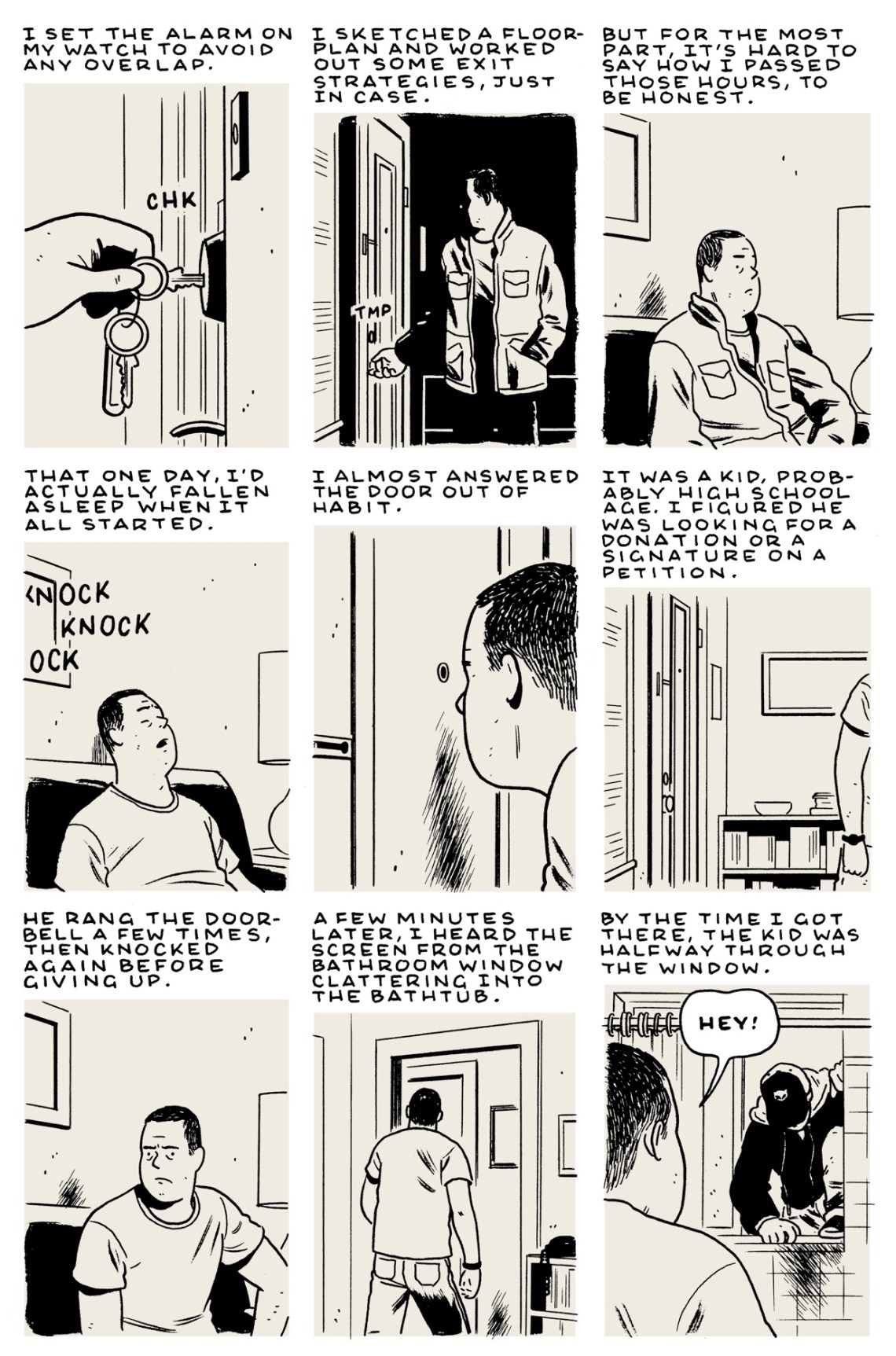

That doesn’t sound so strange, it sounds like compassion. When you write characters in your comics, do you make notes on their body language or their habits before you start to draw them, or do you figure them out as you go along? I’m thinking of the story “Intruders,” in Killing and Dying, where we see the protagonist do a lot of sitting around, standing, and watching before he leaps into action. What is your relationship to sketching people—do you do it regularly?

I know there are a lot of writerly techniques for developing characters, like mapping out their whole backstory or writing a diary in their voice or whatever. I usually don’t do anything like that, but I do a lot of preparatory sketches—usually just quick pencil drawings in a notebook—that serve a similar function. Much of this process is practical, like trying to figure out exactly what the character looks like, or how detailed or cartoony the drawing should be. But I’m also figuring out who the character is as I draw them, and a lot of thoughts and ideas pop into my head but never make it directly onto paper. I feel if I do this part of the process well enough, then the characters are almost like actors who can improvise as the story itself develops.

With regard to “Intruders,” that’s a good example of my finding the character through sketching. I was making a concerted effort to write about a kind of character I’d never written before, and a lot of that story clicked for me when I started drawing that big, burly guy. It was a useful challenge because I couldn’t just fall back on my usual habits of looking in a mirror for reference.

I used to be more of an undercover sketcher, especially when I was traveling or sitting on the subway. But that kind of dropped off when I became a parent, and now when I’m in those situations I’m usually either dealing with my kids or just spacing out. Maybe I’ll get back to that kind of drawing in my old age.

Are you a fan of Cusk’s writing? Whom do you love to read, or go back to, and have your tastes changed since writing a memoir?

Yes, I’m a fan. As someone who’s written his share of autobiographical and semi-autobiographical stories, I felt an instant affinity with her trilogy. But at the same time I felt very surprised and challenged by it, and that was really the aspect that inspired me.

As far as authors I return to, I’ve got some very faded, well-worn copies of books by John Cheever, Raymond Carver, Carson McCullers, Vladimir Nabokov, and Flannery O’Connor that have survived not just many decades but many moves, including when I came to New York from California. That whole series of Vintage Contemporaries, the ones with that uniform spine design, really had a big impact on me when I was younger. Calvin Trillin and Joseph Mitchell are like comfort food for me. I love the Lucia Berlin and Philip K. Dick stories that take place in Berkeley and Oakland, my old stomping grounds. And of course there are too many comics to list, but I sometimes feel like Charles Schulz and Dan Clowes have been with me my whole life.

Since completing The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist, I’ve been immersed in screenwriting. It’s kind of a departure for me, and I feel like, for better or worse, I’m learning on the job. As a result, almost all my reading lately has been screenplays, plays, filmmaker interviews, and film history. I’ve had a stack of books on my desk for the past two years that includes Kenneth Lonergan, Annie Baker, Phoebe Waller-Bridge, Alexander Payne, and the Coen brothers. I’ll devour any kind of “making of” book, even if it’s about a film I’m not a big fan of or, in some cases, that I haven’t even seen.

Did you always want to work in film? Do you like reading screenplays? I’ve read plays regularly with a group of writers over the pandemic, and it’s an incredibly efficient form.

I’ve always loved film and TV, and I actually started making little movies with my dad’s Super 8 camera around the same time I started drawing comics. It’s possible that I pursued a career in comics only because I soon discovered that they were much easier and cheaper to make and required fewer collaborators (a.k.a. friends). I do like reading screenplays, and I’m probably one of the five people left in the world who wishes that publishers like Faber and Newmarket Press were still filling my bookshelves with their screenplay books.

Do you think graphic novelists are like filmmakers, in that both depict the verbal and nonverbal simultaneously?

For the most part, I’ve found that filmmakers and cartoonists are not that similar. I think the art forms have some things in common but are really pretty distinct. I think, in most cases, a person’s personality is either suited to one or the other. I generally gravitate toward chatty, dialogue-heavy films. I’m always more blown away by a beautifully written conversation than any of the flashy visual elements of filmmaking.