“Multiple meter!” That, Robert Farris Thompson insisted, was the key. It was a week into my freshman year at Yale, and the eminent professor of art history was explaining why, when aliens from across the galaxy aimed their radios at Earth, most of the sounds they’d hear would share some common traits. “Funk from New Orleans and samba from Bahia! Salsa from San Juan! House from Detroit and hip-hop, now, from everywhere!” What did they share, these beats that had come to dominate FM frequencies and dance floors worldwide? Thompson broke it down: the sophistication and force of music—Black music—that invited us to absorb and move to more than one rhythm at once. Those rhythms, he emphasized, were traceable to the ancient civilizations of West and Central Africa, from where some ten million people were trafficked to the Americas as slaves between the fifteenth and nineteenth centuries.

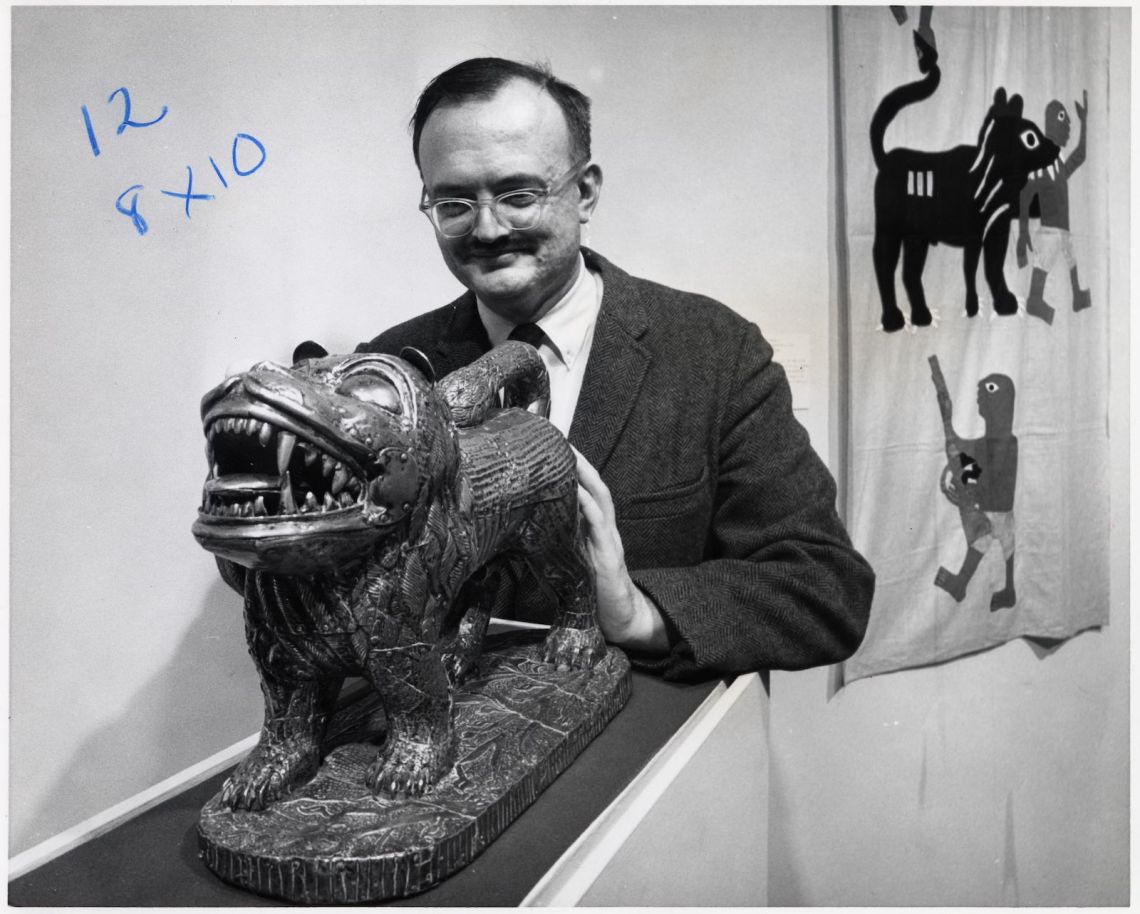

The bearer of this message was an aging white man in penny loafers known to peers and students as “Master T,” a nickname born from the decades he spent with that title as the head of one of Yale’s residential colleges. His aspect may have seemed incongruous to the undergraduates packing one of the biggest lecture halls on campus, but by 1998 Master T had made his flagship course, The Black Atlantic Visual Tradition, hugely popular. Football players and aspiring poets both thrilled to the exhilaration with which he explained that “funk” derived from a Kongo term—lu-fuki—for “good sweat.”

When Thompson died late last year in New Haven, at eighty-eight, the critic Greg Tate eulogized him to a mutual friend of ours as “the master of us all.” A week later, during that winter of too much death, Tate went to the ancestors himself. Tate was not alone in his reverence. “It was very clear,” the critic and scholar Imani Perry wrote last December, “that for this white Texan, our culture was appropriate for rigorous detailed study and that we came into class with a much deeper font of knowledge about it than our peers, who often seemed to sneer with the assumption that we were inadequate.” On Twitter, another of his protégés, the Harvard art historian Sarah Lewis, quoted a line that summed up his message: “until you know how African you are, you will never know how American you are.”

Thompson’s point about “multiple meter” wasn’t just that it had roots in the music of the Kongo and Mandé, the Yoruba and Ewe and Fon. It was that such syncopations, properly engaged, gave physical and motive form to a vital concept: “cool,” which Thompson traced back to the languages of West Africa. The figuration of the cool in music, art, and dance, he argued, was a matter of profound social and political importance. He’d point to an image of Marlon Brando in leather and shades. “Is this cool?” he’d ask, then answer, “No! It’s a pose—but Marlon’s pointing at something.” Next image: a carved ebony head from Benin, its lips pursed, features placid. “This is cool.” The next slide, on the screen above his head, was a video. “So is this.” A dancing woman, encircled by her peers in a Nigerian square, moving to a rapid beat furnished by Bob’s palms on the lectern. Her feet described one intricate tempo, her hips moved to another, her carriage held upright through it all. Her face was a becalmed mask, her level head adorned with a sculpted crown.

This Yoruba dancer, Thompson said, had made herself a living symbol of cool as both worldly aesthetic and philosophy for life—a mode of being whose core tenets involved a sense that no conflict or issue couldn’t be measured and solved; that wearing and showing off your ability to confront moments of stress and joy alike was a moral virtue; that making difficult tasks look easy, whether when playing a bebop tune or facing down a foe, was a virtue, too. The stylized performance of the cool’s “call for parlance, for congress, and for self-confidence” had a part in forging social peace.

Thompson’s famous “canons of the cool” didn’t help ease the impressions of some, especially as his work began to reach a wider readership in the 1980s, that his “hipty-dip tone” and “his stories of conversion to the faith by mambo and Abakua in the ‘50s” had “a faint aroma of Jungle Jim.” That’s how Tate described him in The Village Voice, in a review of Thompson’s landmark book Flash of the Spirit. Tate admitted to having questions about a white man whose romantic paeans to Blackness outstripped those of Tate’s own mother, but conceded that this Afrocentric scholar “knows too much to be ignored. Period.”

Advertisement

*

Thompson’s work grew out of the anthropology of Zora Neale Hurston, Katherine Dunham, and Melville Herskovits: pioneering ethnographers of Black culture in America whose granular readings of folk songs, traditions, and dance crystallized around what Herskovits called “retentions” from Africa. Thompson’s career began as that of Herskovits, who died in 1963, was ending, and thrived as the old focus on retentions was supplanted among Herskovits’s critics and heirs by “creolization.” It ended at a time when Blackness has come to be seen less as a shared inheritance of ethnic pasts than as a social construction: a collective identity born of the Middle Passage and of the pseudoscience of “race.” Paul Gilroy, in his influential 1993 book The Black Atlantic, proposed that cultural forms born of this history and from the travels and interrelation of people from many lands—including European ones—comprised a “counterculture of modernity.” It’s a testament to the complexity and depth of Thompson’s work that it resonated, in varying ways, with all these schools of thought.

No critic caught Thompson’s influence on a generation of artists and writers like Tate. In his 1986 essay “Cult-Nats Meet Freaky-Deke,” Tate wrestled with the complex legacies of cultural nationalism for his bohemian cohort, coming of age a couple decades after the rise of Black Power and the Black Arts Movement. He gave thanks for that era’s avowal of Black creativity and difference, which, he wrote, was vital to his generation’s will toward experimentation and pride. But his generation was also determined to transcend “the jiver parts” of their forebears’ ideology, and their attachment to Africa that could seem based less in knowledge than in mythmaking. The 1980s, he wrote, “are witnessing the maturation of a postnationalist black arts movement, one more Afrocentric and cosmopolitan than anything that’s come before.”

He insisted that his generation of Black artists—unashamed to feel as inspired by punk rock or Proust as by jazz—believed that “the cultural gene pool is for skinny-dipping.” And he made clear that, insofar as this new movement required a “unified field theory” of the roots of Black culture, one scholar was “moving most determinedly” to that aim. “Thompson’s work disproves and demolishes at every turn,” Tate wrote, “the myth that classical African culture doesn’t derive from as systematic and highly evolved a tradition of critical thought as Europe’s.”

Thompson was convinced that there wasn’t a culture in history that hadn’t evolved by allowing its artists to alight upon the forms and wisdom of whatever human tradition they were drawn to. That was true of civilizations writ large, in his pedagogy, including the African ones he knew best. But it was also true at the level of the individual. He said that his upmost aim was “dancing us all toward…becoming ourselves through awareness of others.”

His own dance was shaped by his boyhood in El Paso, where he was born in 1932. It was thanks to his Mexican friends there by the Rio Grande, and to a trip as a teen to their nation’s capital, that Bob encountered the music that set his life’s course. Mexico City after the war was home to a number of leading musicians from Cuba, and Thompson’s exposure to the thrilling sounds of Pérez Prado—the mix of Afro-Cuban clave and swinging horns hawked to the world as mambo—inspired him to take up the congas himself and become an accomplished enough percussionist, in his twenties in New York, to sit in with Tito Puente. Plenty of American kids with a yen for rhythm and pissing off their parents got into mambo in the 1950s. But Thompson followed that yen to Yale, where as a grad student he traced mambo’s roots not just back to the Caribbean but to the ancestral cultures and social systems inseparable from the music he loved.

In 1965 he was among the first art historians in the US to earn a Ph.D. for research focused on African art. He revolutionized that field by insisting that his objects of study couldn’t be properly considered without examining the circumstances of their creation and the philosophies they evinced—ideas more often borne by dancing bodies than written down in books. During extended research trips to the Congo Basin he learned the Bakongo language of its ancient kings and found the seed for the vernacular Cuban exclamation that gave mambo its name.

In Cuba, where many people are descended from enslaved sugar workers who had been brought to the Caribbean from Kongo in the nineteenth century, “mambo” was an exhortation used by musicians urging their fellows, whether caressing a drum or blowing a horn, to “say it!” Thompson heard in it a plain echo of the Kongo mambu—an encompassing term for matters requiring adjudication by a noble empowered, via words declaimed at rites involving drumming and dance, to resolve conflicts and harmonize the social world. It was evidence, to his mind, that this music “never lost the Kongo taste for solving or challenging issues with hard-driving beats.”

Advertisement

He first articulated such ideas, backed by prodigious research, in African Art in Motion and his opus on the Yoruba, Black Gods and Kings, which in 2020 made a cameo appearance, to Bob’s delight, in Beyoncé’s video album Black is King. But the book that brought his work to a wider audience was Flash of the Spirit. Published in 1984, its chapters arrayed the influence of five civilizations—Yoruba, Kongo, Mande, Ejagham, and Cross River—on the lifeways and aesthetics of the Black Atlantic. Continuously in print, it reads like the living footnotes for his lectures, in which he was fond of quoting Zora Neale Hurston’s dictum on Black aesthetics: “Decorate the decoration!”

Thompson’s vocation was not merely to tell you from which specific masks Picasso and Braque “stole fire” a century ago in Paris (mostly those of the Baoulé and Fang, from the Ivory Coast and Gabon). It was also to show how those masks’ elongated features and layered clay surfaces, when donned by wearers charged with weighing heavy matters of law, represented “a meditation on the ancestral sources of justice.” This way of engaging non-Western works of art, using social philosophy as much as aesthetics, was anathema to art historians. It’s easy to forget, given the accolades with which Thompson was later showered by his academic peers, that the most impressive feat of his early career was convincing Yale’s Department of the History of Art that what he wanted to study belonged in their discipline and not, as was then customary for “preindustrial” cultures, in the still-colonial corridors of the Department of Anthropology.

At eighteen, I was still a couple of years from understanding my new professor’s contributions to the mode of cultural criticism Tate envisaged in “Cult-Nats Meet Freaky-Deke.” But Thompson’s canons of cool landed like epiphanies. One day I went to see him at his office carrying a CD by a Bay Area hip-hop group, whose cover art featured a logo—a stick-drawn face with not two eyes but three—that perhaps recalled, Thompson agreed, the belief of Yoruba Babalawos in the extrasensory sight of a “third eye.” Nodding his snowy pate to the jazzy beats of the Hieroglyphics’ 3rd Eye Vision, he took out one of the big notebooks he filled with sketches and names—his encyclopedia of Afro-diasporic culture—and asked me to respell the name of Del tha Funkee Homosapien.

His speaking style was nothing if not, as his devotee David Byrne has put it, “full body.”1 Bob never had a dancer’s physique, but in his lectures he would shuffle across the stage in his loafers before snapping to attention and beating out a precise guaguancó with his palms on the lectern, assuming the bent-kneed position of the dancing rumbero in Havana or nkisi figure from Kongo projected onto a screen above. “Bent knees!” he’d cry. “That’s the position of a human.” He showed us an image of what happens when we forget this: goose-stepping Nazis.

He kept building his encyclopedia of diasporic culture, in his notebooks and on construction paper he spread onto his favorite table at the Union League Cafe in New Haven, where he greeted visitors from Jamaica or Yorubaland or Brooklyn who came to learn and to share knowledge, which he ingested with as much gusto as his oysters. He was a proud role model to generations of students in Yale’s Timothy Dwight College, which he led for thirty years and whose intramural athletes wore t-shirts bedecked with a Yoruba word he held holy, àshe. Exhortation and exclamation in one, it was used by Thompson as a verb: to actualize; to do the thing and do it right.

*

After he earned his Ph.D. Thompson formed many of his closest professional and personal relationships not with fellow academics but with artists, musicians, and sundry diasporic denizens in New York, which he called our “secret African city.”2 Whenever he drove down to New York from New Haven he eschewed the genteel Merritt Parkway for I-95: with its clanging sixteen-wheelers and steely speed, he explained, the interstate was a favored realm of Ogun, the Yoruba orisha of iron and fire. Back when the deejays and graffiti writers who created hip-hop were exponents not of a dominant force in world pop but of a vibrant subculture in the Bronx, he clocked the genre’s Africanist tropes, from rap’s signature boom-boom-BAP to the stop-time pop-and-lock poses of break-dancers in Crotona Park.

His importance to articulating how hip-hop shaped the art world of Manhattan is distilled in the story of his first meeting with Jean-Michel Basquiat. Thompson was in the South Bronx meeting with hip-hop founding father Afrika Bambaataa when an emissary turned up to tell the professor that Basquiat wanted to meet him. Bob rolled down to the studio on the Bowery where Basquiat made the pieces that Tate called “neo-hoodoofied Symbolist poems.” The young artist told him that Flash of the Spirit was his favorite book and gave him the large painting that would hang in his office in New Haven until the end.

Tate’s book Flyboy in the Buttermilk took its title phrase from his much-cited essay on Basquiat, in which he parsed the art-historical import and refractive space-age aesthetics of a Black painter who transcended all the frames within which critics labored to place him. Thompson became our other essential exegete of New York’s signal contemporary artist by insisting that Basquiat’s work was best viewed in the light of the Afro-Atlantic. Many of Basquiat’s canvases, replete with all-cap epigrams and skulls, include motifs he learned from Thompson’s writings on Kongo cosmograms and the Ejagham veneration for the mystical power of stylized script. Thompson, in turn, saw in Basquiat’s interest in the crowned human head an echo of its primacy for the Yoruba, in whose arts it symbolized “the confidence of the people’s monarchic traditions, and the complexity and poise of their urban way of life.”

With Flash of the Spirit, Thompson made his scholarship’s raison d’être “the identification and explanation of some of these mainlines, intellectually perceived and sensually appreciated.” In the decades after that study appeared, he wrote several more books but didn’t manage to finish the one he said he’d been writing, at least in his mind, since Pérez Prado’s congas and cries first “irradiated” his soul in the 1950s. Mambo, for Thompson, was everything. Maybe that’s why he struggled to turn what he experienced in its thrall, as a habitué of the Palladium Ballroom in Manhattan before it closed in 1966, into the magnum opus he long threatened to publish. But Thompson was clear-eyed about its importance to his life’s work: “Music called,” he said, “and art history was the response.” He credited the musical champions of Afro-Cubanidad, his heroes in rhythm and much else, with prompting the investigations that became Aesthetic of the Cool and African Art in Motion and all the rest.

The icons and values of the aesthetic and moral worlds he excavated and celebrated for us all could never be of merely incidental or academic interest. They were a “coaxial cable,” as he put it, connecting the urbane splendors of Africa’s ancient civilizations to much of what’s most potent in ours. Thompson defied anyone to suggest otherwise. “I’m a guerrilla scholar, man,” he told Tate in 1984, “and I take my cues from what I hear.”