“Lygia Pape: Tecelares” at the Art Institute of Chicago is an endlessly surprising exhibition, lyrical, frisky, and stealthily profound—which is a lot to pack into a bunch of mostly black-and-white polygons and circles. An important figure in Brazilian postwar art, Pape, like her fellow travelers Lygia Clark and Hélio Oiticica, began her career dedicated to the philosophical principles and abstract geometries of Concrete Art, a movement that offered progressive artists in Latin America an attractive alternative to figuration, so often the willing handmaiden of state propaganda.* By the late 1950s, however, Pape and many of her peers started to feel they had reached a mechanistic dead end. The Neo-Concrete movement that emerged still used geometric forms, but did so in pursuit of a more sociable and corporeal experience. Its manifesto, written by the poet Ferreira Gullar and signed by Pape, argued for art “as a ‘quasicorpus’ (quasi-body), that is to say, something which amounts to more than the sum of its constituent elements; something which analysis may break down into various elements but which can only be understood phenomenologically.”

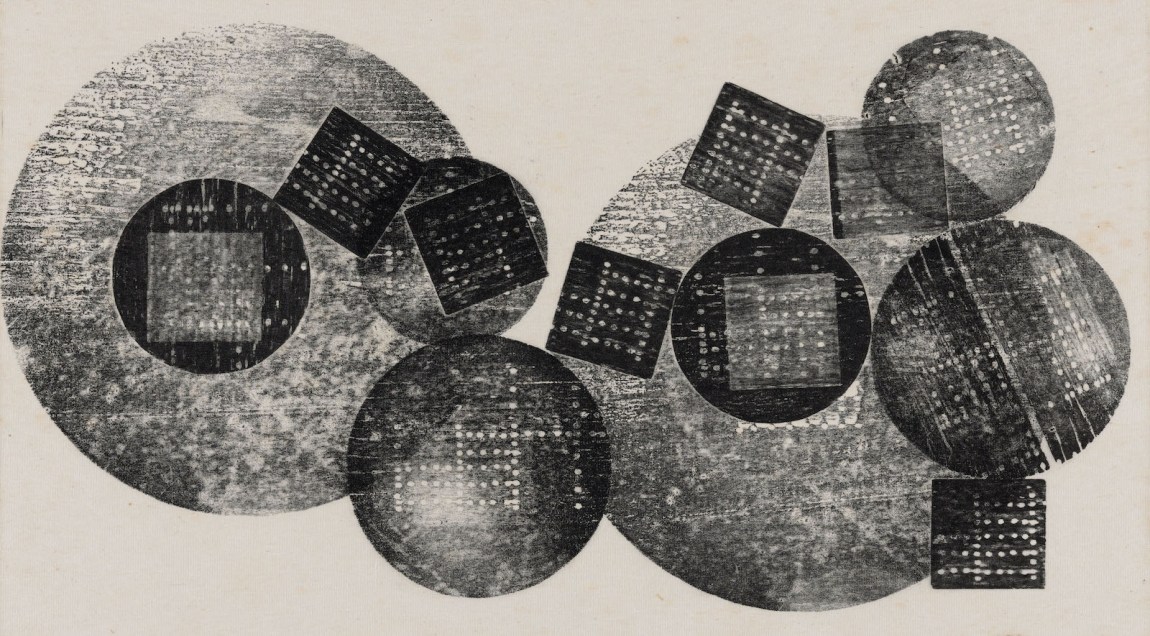

Eventually Pape, Clark, and Oiticica would all turn to more immaterial forms of public engagement—teaching, performance, video, and film—and in the last ten years all three have been the subjects of major New York retrospectives: Clark at the Museum of Modern Art, Oiticica at the Whitney, and Pape at the Met Breuer in a show that stretched from abstract painted reliefs to group performance. In the 1950s, however, Pape was known in the Brazilian press as a gravadora—the printmaker. For a decade, almost all the work she showed consisted of Japanese paper imprinted with inked wooden blocks. Rarely pausing long enough to produce anything as conventional as an edition, she invented composition after composition: interlocking polygons, triangles that spawned smaller triangles, circles disrupted by wood grain or perforated with regular holes. They can appear folkloric or space-age; recall a homespun textile or an array of machine parts. A photo at the entrance to the Chicago exhibition shows Pape seated on the floor with assorted prints and paper scraps, like a child at serious play.

And then she stopped. Pape would later dub most of those printed works Tecelares—a made-up, not-quite cognate for “weavings” in Portuguese. Working with the artist’s estate (Pape died in 2004), the Art Institute curator Mark Pascale has brought together more than one hundred Tecelares and adjacent works created between 1952 and 1960, some of which had not been publicly exhibited since. The catalog constitutes the first substantive study of Pape’s prints, with enlightening essays by Pascale, the art historian Adele Nelson, and the conservator María Cristina Rivera Ramos.

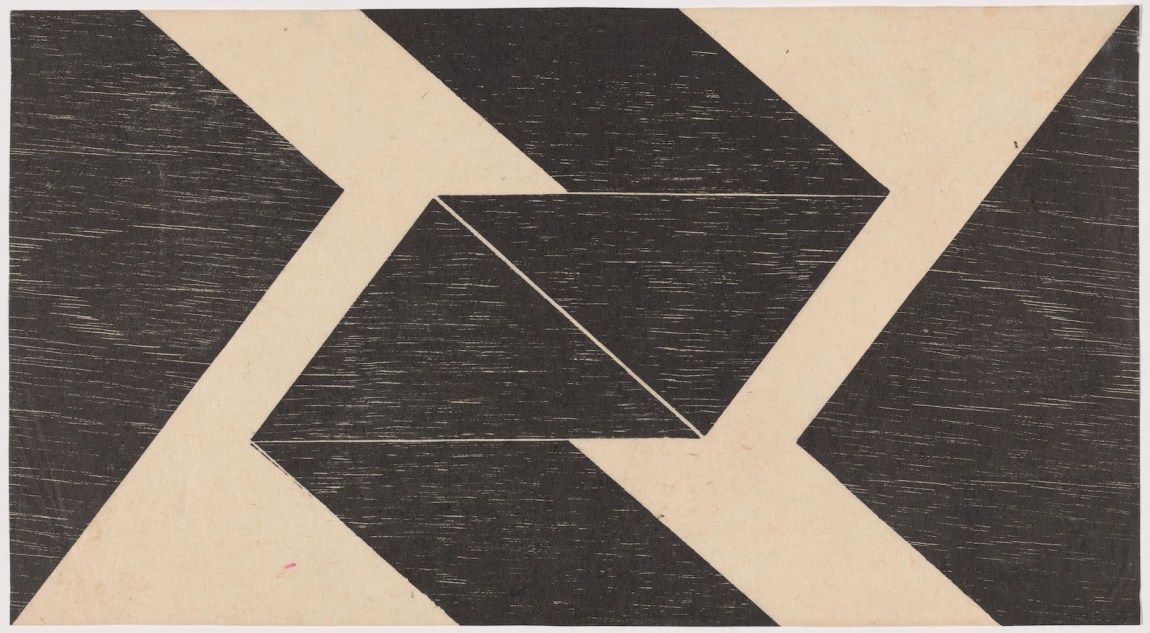

The works on view contain tipsy stacks of rectangles and circles; translucent quadrilaterals that overlap like jagged clouds; inked rectangles that seem to dissolve as though seen through fog or a corroded window screen. Implicit motion is everywhere—shapes topple, bounce, stumble about, nudge each other aside, disperse in some mutually understood dance. Bypassing anything as mechanical as a press, Pape transferred ink by rubbing the back of the paper or pressing blocks on the front in the manner of a rubber stamp. Everything looks homemade, and wall labels point out the faint pencil lines marking where blocks should be stamped. (I recently complained about overly interpretive wall labels, but this show is a model of what good labels do: alert you to things you might miss and then let you get on with it.) To the European notion of “pure” abstraction, Pape added an awareness of indigenous technologies and those commonly regarded as “women’s work.” In her titular allusion to weaving, she made a claim for a kind of unity between her own “high art” activities and a technology commonly associated with women and preindustrial cultures—undervalued objects made by undervalued people.

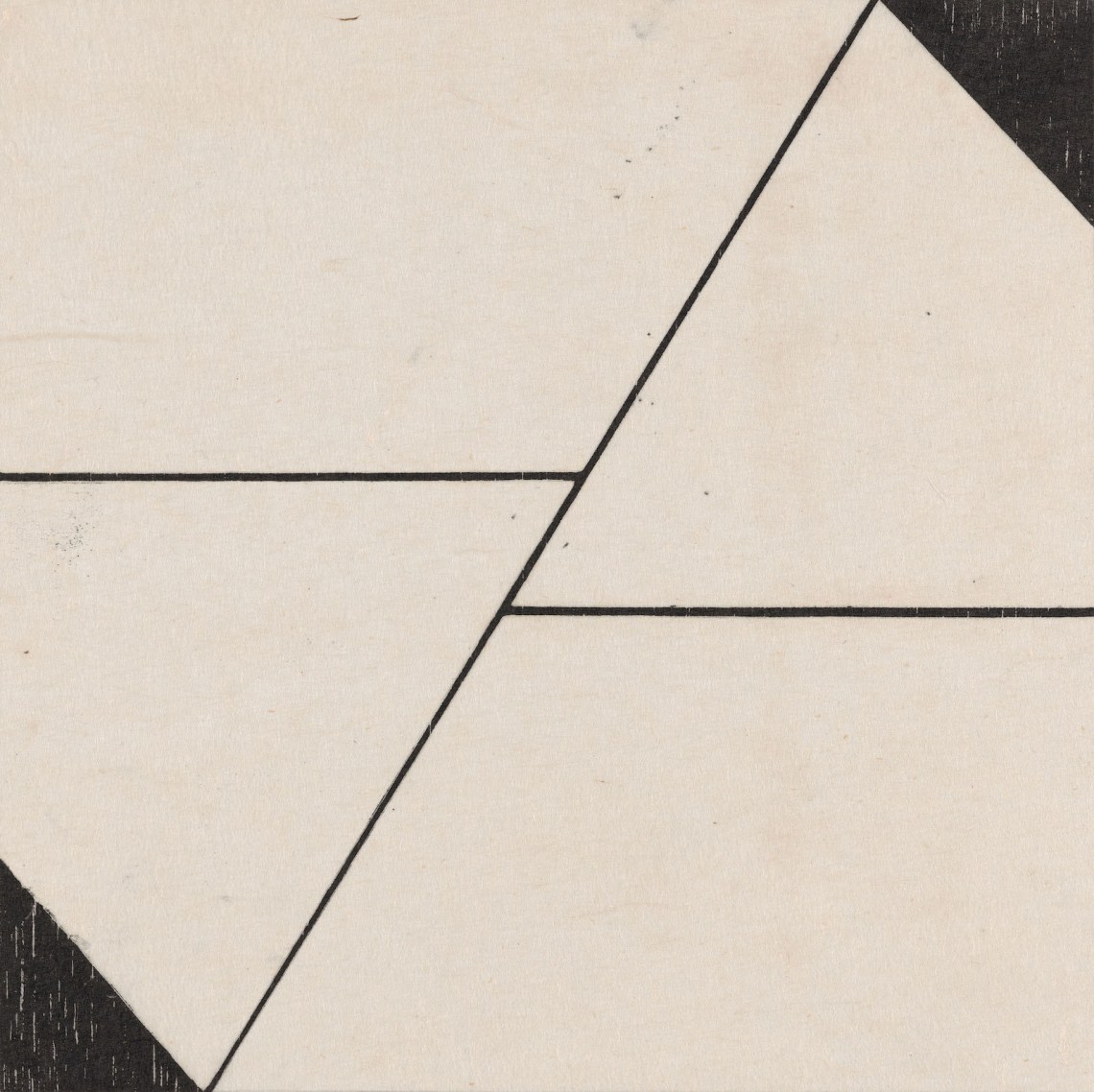

The prints don’t look like weavings, but they carry a similarly tangible integration of image and object, as well as an invitation to unwind the story of their making. Wood grain was clearly a gift. She used it as evidence of continuity (a single pattern that fuses two sides of an incised border) and of disruption (nested chevrons whose borders are visible only through the displacement of grain). Japanese paper offered its own opportunities—organic, eerily smooth, and so diaphanous she could sometimes exhibit the backside of the printed sheet as the final work.

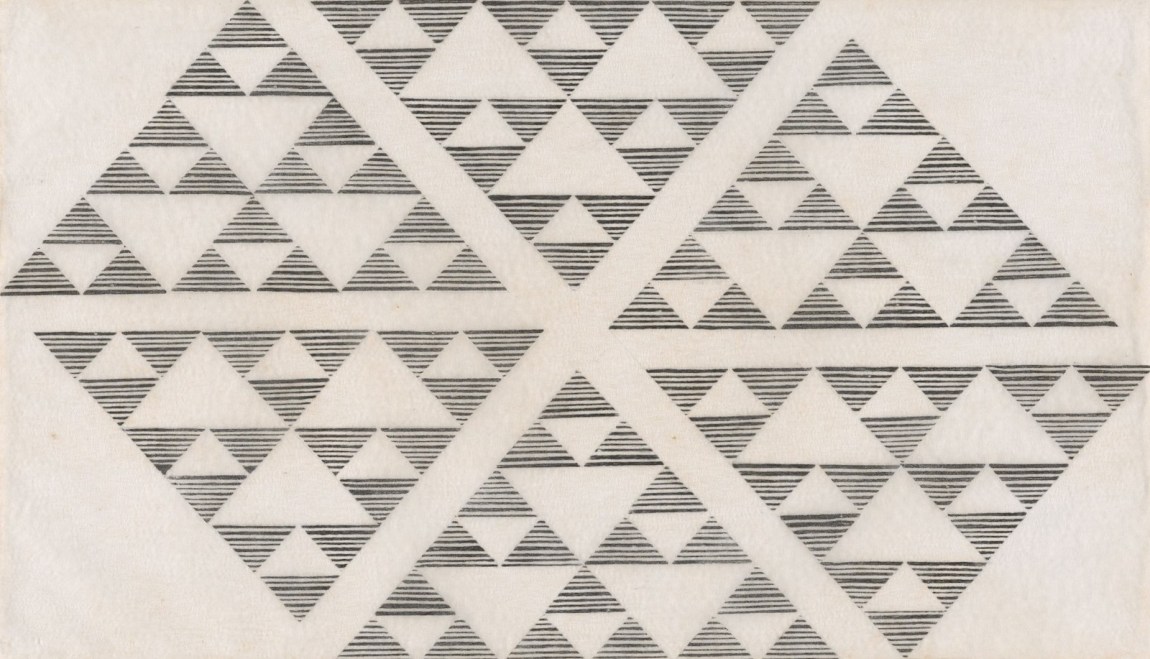

Most of her compositions invite some kind of mental flipping—left-right, up-down, back-front. An extended series from 1955 uses small striated triangles to create open patterns of positive and negative space, often arrayed symmetrically along one or more axes, though it can take some time to figure out exactly how the reflections work. In the process of that slow looking, it becomes clear that the striations are not the results of natural grain but of hand-cut lines that vary slightly from one block to another, and one begins to recognize individual blocks that dance around the page, pointing in a different direction with each iteration.

Advertisement

The Neo-Concrete emphasis on phenomenological experience overlapped with that of American Minimalism, and it is hard to miss the similarity between Pape’s 1957 Tecelar of black stripes arranged like so many nested doorways and Frank Stella’s 1959 Getty Tomb, which uses the same formulation. But where Stella’s eight-foot-wide painting with its edge-to-edge black stripes is still embedded in the confrontational ethos of Abstract Expressionism, Pape’s block of stripes is poised slightly askew on a delicate sheet of paper. The printing block itself is also on view: with its elegant grained surface and faintly inscribed lines, it might be mistaken for a work in its own right, but it points right back to the image on paper. Each is evidence of the other. Nothing stands alone.

Pape’s prints manifest her stated interest in “the principle of ambiguity, no privilege[d] position for a base or bottom (a work could be inverted without being stripped of all its characteristics).” It is a visual argument against hierarchy, and a clue to how her images can slip from being disembodied abstractions (or cutely anthropomorphic ones) to being analogues of social experience and societal possibilities.

The exhibition also includes two later, non-print works. A video from 2000 documents a performance of Pape’s 1958 Ballet Neoconcreto in which people hidden inside white cylinders and rectangular red prisms ambulate about a stage. In life the scale and strangeness of this dance might be riveting, but little of that fascination survives the transfer to the screen. Ttéia 1, B (2002–2022), on the other hand, is magical. Gold nylon threads stretched between two perpendicular walls provoke an illusion of floating, nested cylinders. The impression is of a structure that is not a structure—shapes passing through one another, borne by light. Pape designed the installation in 2002, late in her life. A few years earlier she had said, “Nowadays, I like to feel dissolved in the world.”

The works on paper are smaller, flatter, and less shiny, but they too prompt a sense of the porous interconnectedness of things and beings. As Pascale writes in the catalog, “How remarkable that a print can resonate so long and accomplish so much.”