The death of the musical comedy lyricist Sheldon Harnick on June 23, ten months shy of his centennial, brought forth a torrent of memories that I’d hardly anticipated. Long ago I consigned the formative part that the American musical theater played in my early cultural development to the dead letter office of my consciousness. As I had fully expected, Harnick was identified in the first sentence of virtually every obituary as the man who wrote the lyrics to Jerry Bock’s music for Fiddler on the Roof, the 1964 Broadway production that remains one of the most perennially beloved touchstones of the modern repertoire. But it was their preceding collaboration, She Loves Me, that I and other enthusiasts consider to be their finest work, a masterpiece of rare insight, poetic delicacy, and emotional intimacy, qualities never in overabundance on the Broadway musical stage.

Sheldon Mayer Harnick was born into a Jewish family in Chicago in 1924, the son of a dentist and a homemaker with artistic interests. He began taking violin lessons at age eight, wrote his first songs in high school, and as a teenager played in amateur Gilbert and Sullivan productions. “I was turned on by the patter songs,” he later recalled. “I also realized what a fine poet Gilbert was…. So he became an enormous influence.” Drafted into the army soon after his graduation, he served without incident in the Signal Corps. After the war he enrolled at Northwestern University, famed for its theater department, and received his Bachelor of Music degree in 1949. He soon moved to New York, where he wrote one-off numbers for revues and novelty pieces including “The Merry Little Minuet,” a sardonic ditty about the gloomy state of world affairs that began, “They’re rioting in Africa,/They’re starving in Spain…” and was improbably popularized by the squeaky-clean Kingston Trio.

In the mid-Fifties he met the composer Jerry Bock, an ebullient extrovert antithetical to his own reflective nature, a classic pairing of complementary opposites. They were first hired to write the The Body Beautiful, a musical produced by Richard Kollmar, husband of the influential Hearst newspaper columnist Dorothy Kilgallen. This 1958 dud, about a rich Dartmouth grad who wants to become a boxing champ despite his girlfriend’s disapproval, closed after sixty performances, but what the new duo learned about working together in the process soon paid off handsomely. Their next effort, Fiorello! (1959), a witty and intelligent musical biography of New York City’s reform-minded Depression era mayor, Fiorello H. La Guardia, was a critical and popular hit, and became just the third musical to receive the Pulitzer Prize for drama, after George and Ira Gershwin’s Of Thee I Sing (1931) and Rodgers and Hammerstein’s South Pacific (1950).

But nothing Bock and Harnick did before or after that remotely approached their success with Fiddler on the Roof. Their imaginative retelling (with a book by Joseph Stein) of Sholem Aleichem’s Yiddish Tevye der Milkhiker (Tevye the Dairyman) stories, which he began publishing in 1894, can easily descend into cloying sentimentality at the drop of a shtreimel—particularly in its most famous song, “Sunrise, Sunset,” a slow-waltz catalog of the splendors and miseries of family life, “laden with happiness and tears.” Can there have been a Jewish wedding or bar or bat mitzvah in the past half-century where this tearjerker was not heard? On the other hand, when handled with rigor and restraint—as with Fidler Afn Dakh, the gutsy Yiddish-language version of the show mounted by the National Yiddish Theatre Folksbiene in New York in 2018—Fiddler can be appreciated as a pinnacle of musical drama.

The score is rife with biting wit, such as Tevye’s daughter Tzeitel imitating Yente the matchmaker’s blithe assurance to one of her victims that “I promise you’ll be happy,/And even if you’re not,/There’s more to life than that—/Don’t ask me what.” There is likewise great erudition sprinkled throughout, as in Tevye’s plutocratic fantasy, “If I Were a Rich Man,” delivered with subtlety in the original production by that comedic tornado, Zero Mostel. Along with the material benefits of wealth he contemplates its spiritual comforts: “If I were rich I’d have the time that I lack/To sit in the synagogue and pray/And maybe have a seat by the eastern wall,” in the direction of Jerusalem—at once the age-old focus of Jewish yearning for salvation and a coveted spot that would have required an extra donation to the shul. He even skewers the ever-persistent belief that wealth somehow automatically confers wisdom on its possessors:

The most important men in town would come to fawn on me!

They would ask me to advise them,

Like a Solomon the Wise…And it won’t make one bit of difference if I answer right or wrong.

When you’re rich they think you really know!

When it comes to songs about love recalled in old age, the palm usually goes to Alan Jay Lerner’s lyrics for his and Frederick Loewe’s “I Remember It Well,” written for the 1958 film Gigi and sung by Maurice Chevalier and Hermione Gingold. But their genteel banalities pale beside Harnick’s utterly believable bedtime dialogue between Tevye and his long-suffering wife, Golde (first played by Maria Karnilova, who won a Tony for her portrayal, as did Mostel). One night out of the blue he asks her, as the song’s title goes, “Do You Love Me?”:

Advertisement

She: Do I what?

He: Do you love me?

She: Do I love you?

With our daughters getting married

And this trouble in the town,

You’re upset, you’re worn out,

Go inside, go lie down!

Maybe it’s indigestion.He: Golde! I’m asking you a question!

Do you love me?She: You’re a fool!

He: I know, but do you love me?

She: Do I love you?

For twenty-five years I’ve washed your clothes,

Cooked your meals, cleaned your house,

Given you children, milked the cow.

After twenty-five years why talk about love right now?

Although Fiddler is not my favorite among Bock and Harnick’s works, it’s impossible to dismiss their seriousness of intent. It opened on Broadway at what might now be seen as a historic highpoint for American Jewry. The antisemitism and overt discrimination so evident a generation earlier seemed to be on the wane. As the last of the two and a half million Eastern European Jews who sought refuge in America around the turn of the century approached the end of their lives, Bock and Harnick’s eloquent evocation of Anatevka, a fictive Tsarist shtetl in 1905 that symbolizes the whole of pre-Holocaust Judentum, paid tribute to its citizenry’s endurance, resiliency, and irrepressible love of life in the face of grinding hardship and brutal oppression.

Bock died in 2010 at eighty-one, four decades after he and Harnick last worked together. They split because of a dispute over The Rothschilds, their 1970 musical about the legendary Jewish banking dynasty. The lyricist insisted that the veteran choreographer Michael Kidd be brought in to replace the original dance director, and though Kidd received a Tony nomination for his work, that was curtains for Bock and Harnick.

*

My long-submerged familiarity with the golden age of American musical theater—which is generally agreed to have commenced in 1943 with Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Oklahoma! and lasted at least until Lerner and Burton Lane’s On A Clear Day You Can See Forever twenty-two years later—resurfaced several years ago at a dinner party where I met Frank Rich, who was the chief drama critic of The New York Times from 1980 to 1993 (and lately an executive producer of the hit HBO series Veep and Succession). His unsparing Times assessments of the commercial dreck he had to deal with had established his reputation, to my considerable envy, as the “Butcher of Broadway.”

Rich, who is nine months my junior, reminisced about the many musicals he’d seen in their pre-Broadway tryouts while growing up in a suburb of Washington, D.C., then one of the five principal cities—along with Philadelphia, New Haven, Boston, and Detroit—where costly productions were tinkered with before their opening on Broadway. I was raised in Camden, New Jersey, across the Delaware River from Philadelphia, and my native New Yorker mother passed on to me her love for the populist art form. Encouraged by Rich, I told my own musical comedy origin story: seeing the tryout of Goldilocks, a flop of the 1958 season now considered a Holy Grail among fanatics because it starred the young but already world-weary Elaine Stritch.

That caused him to concede defeat in our friendly competition, but what I already knew, thanks to his touching 1993 Times reminiscence, was that, like me, he holds a special place in his heart for She Loves Me, Bock and Harnick’s musical adaptation of the Hungarian play by Miklós László that inspired the 1940 Ernst Lubitsch film The Shop Around the Corner, that old chestnut of mistaken romantic identity between antagonistic coworkers. Rich and I both saw She Loves Me in 1963—I in its Philadelphia preview at the Forrest Theatre that spring, he at the Eugene O’Neill on Broadway over Christmas vacation—and for me it fully merits its reputation among hardcore theater aficionados as the perfect musical.

It was what has been termed a flop d’estime—a critical success that nonetheless fails to attract a wide audience and closes far too soon. Indeed, it lacked the razzle-dazzle production numbers that would make Jerry Herman’s Hello, Dolly! such a stupendous smash the following year. She Loves Me ran for a respectable 302 performances, but it was finally done in by President Kennedy’s assassination, which cast a pall over the end of the 1963 theater season and the all-important holiday trade.

Advertisement

That original production was brilliantly cast, with Barbara Cook as a lovelorn clerk in a Budapest parfumerie who corresponds anonymously and thereby falls in love with a stranger who turns out, wouldn’t you know, to be a handsome male colleague (Daniel Massey) to whom she wouldn’t give the time of day. (Jack Cassidy won a Tony for his role as their sleazy womanizing confrere, Steven Kodaly.) I can still vividly summon up entire scenes, including the hush that settled over the theater as Cook began her soaring Act I aria, “Will He Like Me?,” a plangent outburst of neurotic self-doubt and stifled sexual longing in which she wonders, as she gets ready to meet her anonymous interlocutor for the first time:

Will he like the girl he sees?

If he doesn’t, will he know enough to know

That there’s more to me than I may always show?

Will he like me?Will he know that there’s a world of love

Waiting to warm him?

How I’m hoping that his eyes and ears

Won’t misinform him.

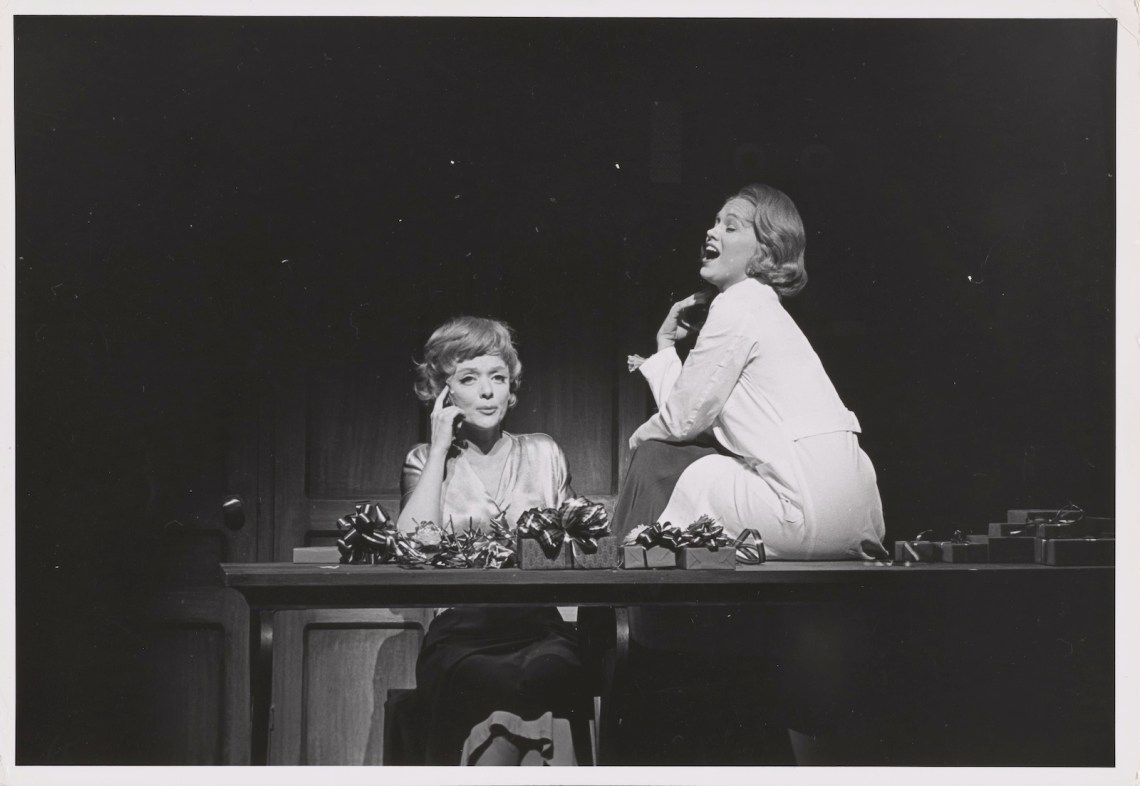

But my favorite She Loves Me number—that word seems slighting for the sublime, almost Mozartean duet I’m about to describe—remains “I Don’t Know His Name,” in which Cook’s character, Amalia Balash, confides to her more worldly fellow salesclerk, Ilona Ritter (portrayed by the pluperfect Barbara Baxley), that she’s fallen in love with her mystery man:

When I undertook this correspondence,

Little did I know I’d grow so fond;

Little did I know our views would so correspond.He writes me what his feelings are

On Shaw, Flaubert, Chopin, Renoir.

The more I read, the more I find

We’re one in mind and heart.I know the kind of home we’d share,

The books, the prints, the music there,

A home, a life, that’s warm and full

And rich in love and art.

In the first half of Bock’s intricately contrapuntal composition, Amalia expresses her heartfelt aspirations, which in the second portion are questioned by Ilona’s terse interpolations, a contrast made sharper by Cook’s dulcet soprano versus Baxley’s dissonant twang. While Amalia obliviously sings “He thinks as I, he feels as I/He shares the same ideas as I,” Ilona realistically interjects, “And another small detail, that you haven’t yet mentioned/I am speaking of sex dear, when you and he are all alone.” I first saw the musical not long before I turned fifteen, as I was busily creating a new, adult persona for myself in which high culture would foster the same kind of ideal psychic home Amalia dreamed of, “rich in love and art.”

In his Guardian obituary of the lyricist, Michael Coveney wrote that among the seven Bock and Harnick collaborations She Loves Me and Fiddler stand out as “classic examples of the romantic, yet socially observant, beautifully crafted, and spiritually impassioned Broadway musical at its best.” I’ve always cynically suspected that the painful commercial disappointment of She Loves Me impelled its creators to choose Fiddler as a surefire winner for their next outing. As Harnick reminisced years after his most crushing disappointment,

I had lavished so much love on the show (as had everyone connected with it) that its apparent rejection by the public was deeply depressing to me…. I don’t think anything in my entire career has given me more satisfaction than seeing the way in which over the years She Loves Me rose from the ranks of dormant musicals, achieved and then graduated from the status of “cult” musical, and went on to win general audience acceptance and affection.

A Broadway happy ending at its most gratifying.