Jennifer Egan’s new novel is a moving humanistic saga, an enormous nineteenth-century-style epic brilliantly disguised as ironic postmodern pastiche. It has thirteen chapters, each an accomplished short story in its own right; characters who meander in and out of these chapters, brushing up against one another’s lives in unexpected ways; a time frame that runs from 1979 to the near, but still sci-fi, future; jolting shifts in time and points of view—first person, second person, third person, Powerpoint person; and a social background of careless and brutal sex, careless and brutal drugs, and carefully brutal punk rock. All of this might be expected to depict the broken, alienated angst of modern life as viewed through the postmodern lens of broken, alienated irony. Instead, Egan gives us a great, gasping, sighing, breathing whole.

Like her earlier work, it is dark and often cruel. But there is a new buoyancy to this novel as well—a buoyancy of tone, of technique. With great openness of spirit, fluency, and a comic vision that balances her sharp eye for the tragic, Egan has employed every playful device of the postmodern novel with such warmth and sensitivity that the genre is transcended completely. We are left with a narrative that is elegant, revealing, and urgent. Because the novel looks both forward and backward in time, and because the facts of its characters’ lives are doled out so unexpectedly, so fully out of the obvious sequence of events, the reader acquires an omniscience that is almost godlike, but is nevertheless shadowed with mystery. We know certain things must happen, will happen, essentially have happened, since the author is able to tell us so. But we don’t know how. Egan’s characters encompass not only their pasts but their futures as well.

In the first chapter, we meet Sasha, a thirty-five-year-old passing for twenty-eight who, we learn in a few casual asides, was abandoned by her father when she was six, lost a friend named Rob in college, went to NYU, and worked for twelve years for a record producer named Bennie Salazar. All of these subjects will arise again in later chapters, each one imperatively in the present tense, each one the story not of Sasha but of Rob or Bennie or one of the many other characters. And yet from Rob’s story, from Bennie’s, from Sasha’s uncle, we catch glimpses of Sasha, sometimes fleeting, sometimes rich and full. Egan turns her slowly in the light and lets us see a new facet of a person who becomes more and more interesting to us.

The book begins with Sasha recounting her most recent shoplifting exploit to her psychiatrist. Called “Found Objects,” it is a story of confusion and shame and thrilling excitement. Bits of the past lie enshrined on a table in Sasha’s small apartment, a source of torment and pride—a child’s scarf, pens, a set of binoculars.

Rather than collect and display his shame on a table like Sasha, her boss, Bennie, carries his shame around with him. Instead of stolen wallets, he is weighted down with moments of humiliation from the past that he scribbles on scraps of paper when he recalls them. “Kissing Mother Superior, incompetent, hairball, poppy seeds, on the can.” Sasha, seeing the list, thinks they are names of songs—“‘Kissing Mother Superior’ is my favorite”—and so they might be. Music, in Egan’s hands, is not an accompaniment or a background tune: it is part of the mayhem of life.

As is the music business. “The album’s called A to B, right?” says Bosco, one of Bennie’s musicians, plotting a comeback. “And that’s the question I want to hit straight on: how did I go from being a rock star to being a fat fuck no one cares about?” The comeback, it turns out, will include a grueling tour by this sickly, grotesquely obese has-been who can hardly walk—a tour that will surely kill him. “That’s the whole point. We know the outcome, but we don’t know when, or where, or who will be there when it finally happens. It’s a Suicide Tour.”

If all the characters in A Visit from the Goon Squad are inevitably on their own Suicide Tour—where else are we all headed, after all?—they are also, some of them, survivors who, after so much running away, so much drunken stumbling, so much ambitious clawing, and so much aimless yearning, have found what they didn’t know they wanted where they least expected it. It is this sense that distinguishes Egan’s book from one more clever piece of prose about disconnected and dissipated young people in New York City and makes it a rich and unforgettable novel about decay and endurance, about individuals in a world as it changes around them, as grand in its scope as, say, Buddenbrooks or Tanizaki’s The Makioka Sisters.

Advertisement

In one of the most evocative chapters, “Safari,” which ran as a story in The New Yorker, a powerful and intensely selfish music producer named Lou has taken his son Rolph, eleven, and his daughter Charlie, fourteen, on a safari in Africa along with Lou’s college-aged girlfriend, Mindy. We are steeped in the immediacy of this adventure: what the children notice; what they don’t see; the odd forced intimacy of strangers traveling together; the shared excitement of physical danger; the currents of sexual tension. As they sit on a beach together discussing their father, Rolph is still a boy, but Charlie is a painfully recognizable adolescent, cynical and raw, dropped into this stew of seething adult innuendo:

“I think he’s going to marry Mindy,” Charlie says.

“No way! You said he didn’t love her.”

“So? He can still marry her.”

And then, instantly, Charlie is no longer an adolescent, no longer on the sandy beach in Africa with her little brother:

Charlie shrugs. “I know Dad.”

Charlie doesn’t know herself. Four years from now, at eighteen, she’ll join a cult across the Mexican border whose charismatic leader promotes a diet of raw eggs; she’ll nearly die from salmonella poisoning before Lou rescues her. A cocaine habit will require partial reconstruction of her nose, changing her appearance, and a series of feckless, domineering men will leave her solitary in her late twenties, trying to broker peace between Rolph and Lou, who will have stopped speaking.

Rather than waiting in suspense to see what choices a character will make and what impact they will have on the future, the reader is forced to recognize that Egan’s characters have no choices left. The result is an unexpected, almost painful empathy, and a narrative suspense that moves in every direction at once.

At the end of “Safari,” Charlie persuades the self-conscious Rolph to dance with her, and Egan gives us an image of Charlie in the future looking back at Rolph, who has no future, an image so twisted and bound in the complexities of time and tragedy and joy that it seems freed, seems almost to be floating:

This particular memory is one she’ll return to again and again, for the rest of her life, long after Rolph has shot himself in the head in their father’s house at twenty-eight: her brother as a boy, hair slicked flat, eyes sparkling, shyly learning to dance. But the woman who remembers won’t be Charlie; after Rolph dies, she’ll revert to her real name—Charlene—unlatching herself forever from the girl who danced with her brother in Africa. Charlene will cut her hair short and go to law school. When she gives birth to a son she’ll want to name him Rolph, but her parents will still be too shattered. So she’ll call him that privately, just in her mind, and years later, she’ll stand with her mother among a crowd of cheering parents beside a field, watching him play, a dreamy look on his face as he glances at the sky.

When we first meet Lou, in the chapter called “Ask Me If I Care,” he is a sleazy older man who picks up the seventeen-year-old Jocelyn. Her best friend, Rhea, tells the story, excited when Lou invites both girls to a fancy restaurant, when he slips them a vial of cocaine, when he walks down the street with an arm around each of them. “Lou is a music producer who knows Bill Graham personally,” Rhea, a girl with green hair and safety pin piercings, tells us, as breathlessly as the child she really still is. The episode that follows is sordid in the extreme, yet this chapter remains oddly charming, for we hear the voice of a resilient seventeen-year-old—knowing, precocious, reckless, loyal, sharp-eyed, blinded by the desire to grow up, and, somehow, pure. The novel has the impatient pull of a mystery story and the big messy scope of the nineteenth century, but at its core is a surprising, unlikely theme: innocence. Innocence betrayed, innocence lost, innocence fondly or bitterly remembered.

When Jocelyn and Rhea meet again at the age of forty-three, they stand together at Lou’s sickbed and Jocelyn contemplates the impossibility of a future that has already arrived—“So this is it—what cost me all that time. A man who turned out to be old…”—and the prediction of a future from the past—“[Rhea’s] skin hangs loose—freckled skin ages prematurely, Lou once told me, and Rhea is all freckles. ‘Our friend Rhea,’ he said, ‘she’s doomed.'”

Advertisement

For the most part, all the characters in A Visit from the Goon Squad seem doomed, and far from innocent. They are shoplifters, runaways, adulterers, liars, derelicts, schizophrenics, and drug addicts. “Seventeen,” Jocelyn thinks,

hitchhiking. He was driving a red Mercedes. In 1979, that could be the beginning of an exciting story, a story where anything might happen. Now it’s a punch line. “It was all for no reason,” I say.

“That’s never true,” Rhea says. “You just haven’t found the reason yet.”

The whole time, Rhea knew what she was doing. Even dancing, even sobbing. Even with a needle in her vein, she was half pretending. Not me.

“I got lost,” I say.

The question of the novel, the question every character asks, is: How did I get lost? How did I get from there to here?

“At what precise moment did you tip just slightly out of alignment with the relatively normal life you had been enjoying theretofore,” asks a journalist who has ended up in jail for the attempted rape of an actress he was interviewing, “cant infinitesimally to the left or the right and thus embark upon the trajectory that ultimately delivered you to your present whereabouts—in my case, Riker’s Island Correctional Facility?”

This occurs in a blackly comic chapter, a parody of the old new journalism “profile” that went wrong. Egan is shrewd about journalism and about popular culture in general, and she ends the story with this perfectly pitched account of the press’s reaction to the journalist’s crime:

Front-page headlines, followed by a flurry of hand-wringing follow-up articles, editorials and op-ed pieces addressing an array of related topics: the “increasing vulnerability of celebrities” (The New York Times); the “violent inability of some men to cope with feelings of rejection” (USA Today); the imperative that magazine editors vet their freelance writers more thoroughly (The New Republic), and the lack of adequate daytime security in Central Park.

In an even darker and funnier chapter, Egan tracks the victim of the attempted rape to her later, has-been years. She is used by Dolly, a has-been PR maven, in Dolly’s comeback scheme to make a vicious dictator likable; the New York world of public relations is satirized with the merciless intelligence of Evelyn Waugh. But Egan’s view of life is too subtle and too joyous (however ironically) to stop at satire, even high-level Waughian satire. There is a terrifying presence in the story, a cold and calculating miniature New York power broker, Dolly’s daughter Lulu:

She was part of a weave of girls at Miss Rutgers’s School…. It wasn’t thread holding these girls together; it was steel wire. And Lulu was the rod around which the wires were wrapped. Overhearing her daughter on the phone with her friends, Dolly was awed by her authority: she was stern when she needed to be, but also soft. Kind. Lulu was nine.

Egan does not spare Lulu, or Dolly for that matter, the lash of her satirical wit. But she does not deny them the sweetness of life, either. Sweetness appears in the form of the actual taste of a star fruit:

Lulu took the dusty, unwashed fruit, wiped it carefully on her short-sleeved polo shirt, and sank her teeth into its bright green rind. Juice sprayed her collar. She laughed and wiped her mouth on her hand. “Mom, you have to try this,” she said, and Dolly took a bite. She and Lulu shared the star fruit, licking their fingers…. Dolly felt oddly buoyant. Then she realized why: Mom. It was the first time Lulu had spoken the word in nearly a year.

Sweetness appears, too, in a happy (however ironic) ending: the sinister farce becomes an enchanting fairy tale. For Egan, the alchemy of life, of time, so unpredictable, so random, not only changes the gold of youth into the shame and loss of age. In this novel, a rock star can become a bum, but a bum can also become a rock star and, sometimes, the lost can find their way back.

When Sasha’s Uncle Ted is sent to find her in Naples after she has run away, he spends most of his time going to museums. He has no intention of looking for his niece. Once she was a lovely child, but she

fled an adolescence whose catalog of woes had included drug use, countless arrests for shoplifting, a fondness for keeping company with rock musicians…, four shrinks, family therapy, group therapy, and three suicide attempts…. She’d become a glowering presence…. He wanted nothing to do with Sasha. She was lost.

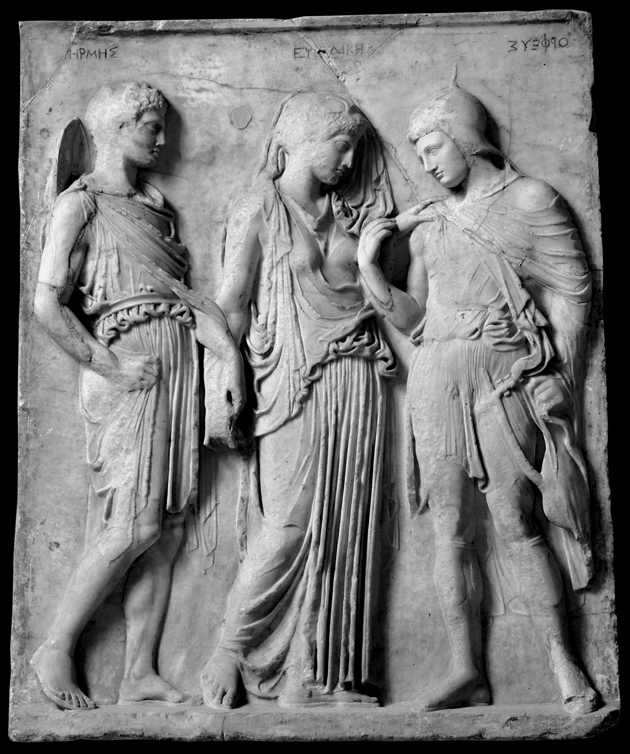

Egan leads Uncle Ted to the Museo Nazionale and its beautiful marble relief of classical, wrenching loss: Orpheus and Eurydice.

What moved Ted, mashed some delicate glassware in his chest, was the quiet of their interaction, the absence of drama or tears as they gazed at each other, touching gently. He sensed between them an understanding too deep to articulate: the unspeakable knowledge that everything is lost.

Yet when Ted finally does find his niece, when he turns back to take a second look at her, his gaze does not condemn Sasha to Hades. It leads her back to the world. Later, we discover Sasha as an adult. She has finished college. She is married. She has a son, Lincoln, who is slightly autistic, and a daughter who is the narrator not of the story, exactly, but of the Powerpoint slide presentation that makes up this improbable chapter. Doesn’t sound like a promising poetic medium, does it? But it is deeply stirring, a linked series of images of the dailiness of family love and conflict. Lincoln is obsessed with pauses in rock songs. His father cannot understand his interest and, uncomfortable with Lincoln’s droning explanation, which is not an explanation at all but a recited list of rock-and-roll pauses, he screams at him. As Lincoln bursts into tears, Sasha, white-faced and furious, leans close to her husband and says softly:

The pause makes you think the song will end. And then the song isn’t really over, so you’re relieved. But then the song does actually end, because every song ends, obviously, and THAT. TIME. THE. END. IS. FOR. REAL.

Egan is a generous writer, as well as an exacting one. She is not afraid of pauses, of quiet contentment, even in the violent stream of life that rushes along toward death. She is one of the most talented writers today, and A Visit from the Goon Squad is her best book. At the end of it, we wonder, as we have throughout this softly devastating novel, at life’s cruelties and at its benevolence.

This Issue

November 11, 2010