1.

The nearly universal acclaim that greeted the High Line—the linear greenway built between 2006 and 2014 atop an abandoned elevated railway trestle on Manhattan’s lower west side—reconfirmed the transformative effect parks can have on the quality of urban life.1 Real estate prices have soared in the vicinity of this one-and-a-half-mile-long wonder of adaptive reuse, and the surrounding neighborhood is now among the trendiest and costliest in town—thousands visit it daily, many from abroad. Yet however much the High Line has enriched the postmillennial megalopolis (economically not least of all), its social effects pale in comparison to the revolutionary vision of the public park as promulgated by its greatest American exponent, the nineteenth-century polymath Frederick Law Olmsted.

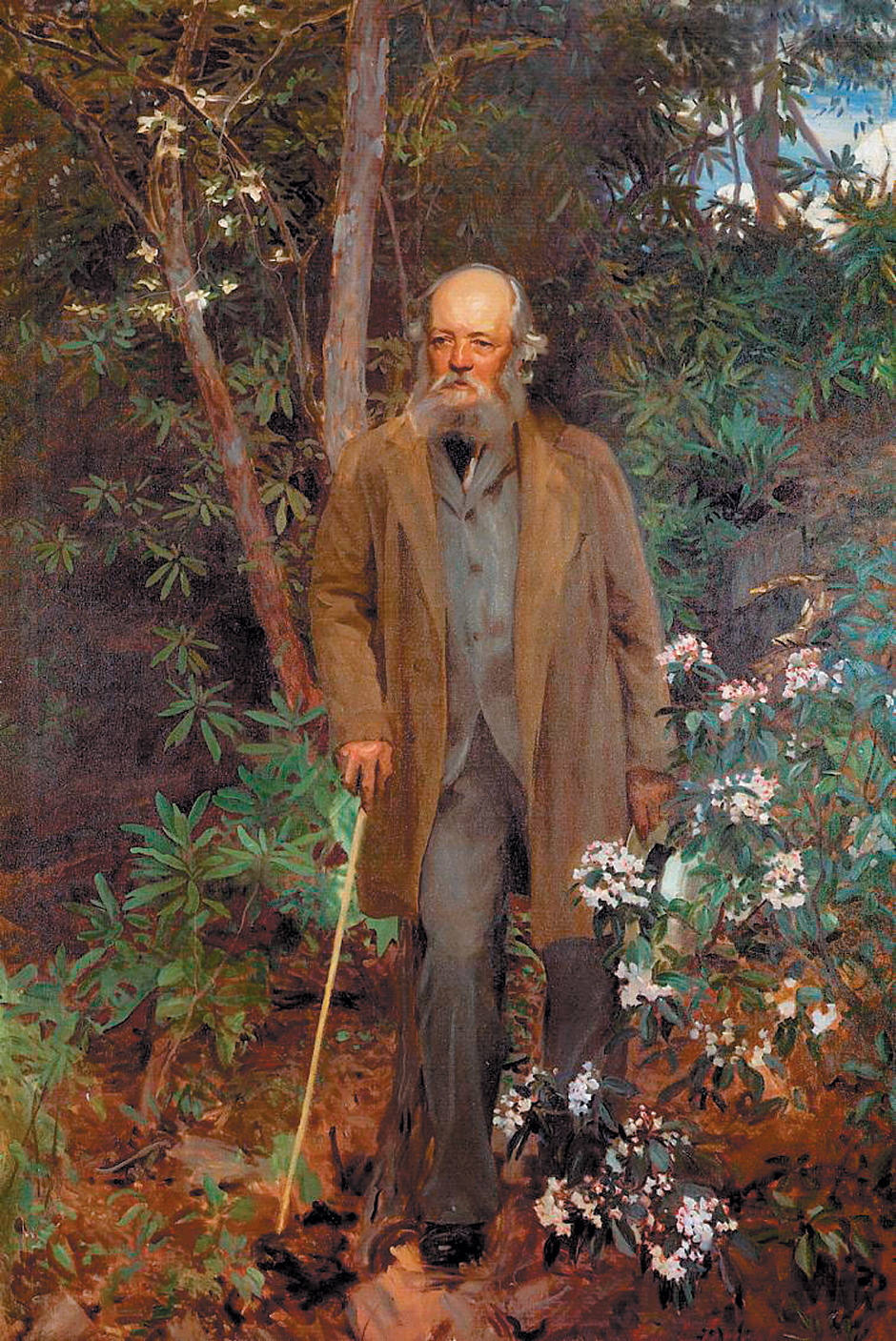

Besides being an experimental farmer, prolific journalist, crusading publisher, military health care reformer, and insightful social critic, Olmsted was also the greatest advocate and impresario of the public realm this country has ever produced. Now best remembered as the codesigner, with the British-born architect Calvert Vaux, of New York’s Central Park of 1857–1873, he was even more important as the veritable inventor of landscape architecture as a modern profession. For apart from Olmsted’s exceptional and apparently innate abilities as a horticulturist—he had little formal training—he systematically conceived the large-scale reshaping of the natural terrain to an extent unimaginable to such illustrious and influential antecedents as Capability Brown in Georgian England and Andrew Jackson Downing (Olmsted’s beloved mentor) in pre–Civil War America.

Olmsted can also be said to have Americanized high-style landscape design, for despite all he learned from British sources about felicitous composition—there is an almost cinematic quality to his gradual revelation of one breathtakingly arranged Arcadian tableau after another—whenever possible he used native species to make his schemes seem like spontaneous emanations of the ecology rather than artificial impositions. Though he was hardly averse to transporting the best available plant material over long distances, and had mature specimen trees and shrubs for Central Park shipped in quantity from England, Olmsted always closely studied local settings for indigenous characteristics that he reproduced with astounding fidelity. Likewise he shunned the strenuous exoticism of Victorian gardening, with its cedars of Lebanon, Argentinian pampas grasses, Mexican agaves, and Norfolk Island pines that flaunted horticulture’s new imperial reach.

Olmsted and his collaborators created scores of parks large and small—in Boston and Fall River, Massachusetts; Baltimore; Bridgeport, Hartford, New Britain, and New London, Connecticut; Chicago; Detroit; Louisville, Kentucky; Milwaukee; Montreal; Buffalo, Newburgh, and Rochester, New York; Newport, Rhode Island; Philadelphia; and San Francisco. He also laid out campuses for the University of California at Berkeley, Stanford University in Palo Alto, and the University of Chicago; Mountain View Cemetery in Oakland, California; as well as one of America’s earliest planned suburbs, Riverside, Illinois. He was responsible for the nation’s first state park—the Niagara Reservation, which got rid of the commercial mess that disgraced the famous waterfalls. At his urging the Yosemite Valley was put under federal jurisdiction, the first public land to be thus protected, and his 1896 report to Congress about the valley is now seen as a mission statement for the then- nascent National Park movement.

Central Park, which launched Olmsted’s landscaping career and inspired communities across the country to commission similar projects from him, emerged at a pivotal moment in the recognition of our environmental treasures and their increasing endangerment. A distinctively American form of nature worship—exalted through the writings of the Transcendentalists Emerson and Thoreau, the poetry of William Cullen Bryant, and the art of Hudson River School painters including Thomas Cole and Frederic Edwin Church—grew into a widely accepted nonsectarian sort of spirituality. This resulted in a significant change in public attitudes toward the environment, which for the first two centuries of European settlement in the Western Hemisphere was more about despoilment than preservation. Lewis Mumford later called this shift “an effort to make reparations to nature.”

The saga of Central Park began in 1844, when Bryant wrote a New York Post editorial that urged the country’s burgeoning metropolis to establish an appropriately grand public pleasure ground. The idea languished in the politically corrupt city, where no official activity was free from favoritism and graft. Under the so-called spoils system, the elected party had absolute control over public funds and distribution of municipal jobs, with abrupt shifts in allocations and appointments when power changed hands. High among Olmsted’s many accomplishments was his ability to buck this entrenched order and bring his dream to fruition.

The seed of that vision was planted in 1850 during his trip to Europe to study new farming methods, though as always Olmsted’s restless eye absorbed everything of interest. Soon after debarking in Liverpool he visited Birkenhead Park of 1841–1847 in the eponymous town across the River Mersey from the port. Laid out by Joseph Paxton—the landscape gardener who with the engineer Charles Fox designed the Crystal Palace of 1850–1851 in London—the 125-acre Birkenhead tract was the earliest urban park in Britain developed with public funds and open to all classes.

Advertisement

This represented an enormous advance in the gradual democratization of civic culture that began during the Enlightenment. Just as the establishment of the first public museums in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries extended the audience for art beyond the aristocracy, so Paxton improved upon forerunners such as Green Park and Hyde Park in London, which were created from former royal hunting preserves and open only to gentlefolk.

Olmsted’s perceptive 1851 report on this innovation, “The People’s Park at Birkenhead, near Liverpool,” is among the forty-seven essays, memoranda, and excerpts from his travel dispatches, along with sixty letters, collected in the Library of America’s long-awaited and thoroughly inspiring Frederick Law Olmsted: Writings on Landscape, Culture, and Society, authoritatively edited by the preeminent expert on the master, Charles Beveridge. The seminal essay on the People’s Park epitomizes not only Olmsted’s breezy, conversational, inimitably American voice, but also predicts, in startlingly prescient detail, what within a decade would become Central Park. His text reveals that it was not stylistic considerations that took precedence for him, but rather a design’s social implications. As he wrote of that momentous field trip:

In studying the manner in which art had been employed to obtain from nature so much beauty,…I was ready to admit that in democratic America, there was nothing to be thought of as comparable with this People’s Garden. Indeed, I was satisfied that gardening had here reached a perfection that I had never before dreamed of…. We passed through winding paths, over acres and acres, with a constant varying surface, where on all sides were growing every variety of shrubs and flowers, with more than natural grace, all set in borders of greenest, closest turf, and all kept with most consummate neatness. At a distance of a quarter of a mile from the gate, we came to an open field of clean, bright, green-sward, closely mown, on which…a party of boys…were playing cricket.

Beyond this was a large meadow with rich groups of trees, under which a flock of sheep were reposing, and girls and women with children, were playing. While watching the cricketers, we were threatened with a shower, and hastened back to look for shelter, which we found in a pagoda…. It was soon filled…and I was glad to observe that the privileges of the garden were enjoyed about equally by all classes. There were some who even were attended by servants, and sent at once for their carriages, but a large proportion were of the common ranks, and a few women with children, or suffering from ill health, were evidently the wives of very humble laborers….

All this magnificent pleasure-ground is entirely, unreservedly, and forever the People’s own. The poorest British peasant is as free to enjoy it in all its parts, as the British Queen.

During the 1840s, New York City was flooded by somewhere between a million and a million and a half immigrants, mainly Irish and German, who were largely unaccustomed to living in a dense, heterogeneous urban setting. Olmsted grasped how a park like Birkenhead could serve New York as a vast outdoor classroom for mass acculturation, where uneducated newcomers would be on an equal footing with the established citizenry and observe modes of improving behavior—in dress, deportment, and leisure pursuits—that they otherwise might not encounter. Also in Olmsted’s article we find a veritable checklist of features later realized in the 843-acre Central Park: the serpentine pathways, the Mall shaded by American elms, the grassy Sheep Meadow, the glades and underbrush of the Rambles, and the spacious ball fields of the Great Lawn. Even the Greensward Plan, the name that Olmsted and Vaux gave their competition-winning New York design, is prefigured here.

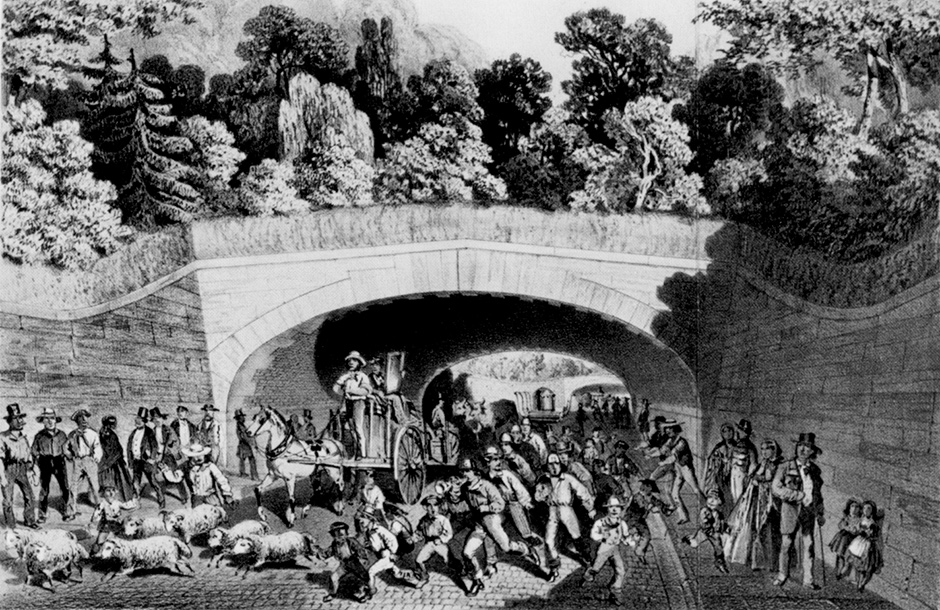

Central Park was laid out four decades before Manhattan’s first automobile fatality in 1899, but urban equine traffic was also often deadly; in 1900 there were some two hundred horse-related deaths in New York City. Thus Olmsted and Vaux’s strict division of circulation in the park acknowledged the ever-present danger of such accidents by consigning heavy east–west vehicular traffic to crosstown transverses sunk well below surface level, while above-grade pedestrian footpaths dipped beneath north–south roadways through small bridges and short tunnels. (The partners, who until they ended their partnership refused individual credit for any specific design solution, seem to have gotten this idea from a pedestrian underpass in John Nash’s Regent’s Park of 1812–1835 in London.)

Advertisement

This concept of dual circulation soon became an article of faith among progressive planners in the United States and Europe. Clarence Stein and Henry Wright’s much-praised 1929 design for Radburn, New Jersey—touted as the “New Town for the Motor Age”—so effectively segregates cars and people that children can walk to local schools and playgrounds without crossing a street. Stein, whose Central Park West apartment overlooked the 65th Street Transverse, said that he discovered what became known as “the Radburn idea” simply by peering out his front window.

Yet for all the priority Olmsted and Vaux gave to traffic patterns, it remains hard to believe that almost everything one now sees in Central Park is manmade. This impression depends entirely on their adherence to the naturalistic ethos of the eighteenth-century British Romantic landscape movement, which supplanted the strictly formal, symmetrical, geometric approach typified by the seventeenth-century French master André Le Nôtre, who in turn drew on earlier Italian Renaissance models. In contrast, the softly undulating outlines and gentle contours of the new British landscape style, which came into vogue around 1750, evoked the so-called line of beauty expounded by William Hogarth and other aesthetic theorists who believed that the graceful Rococo S-curve was the basis for all visual harmony.

Capability Brown and his principal follower, Humphry Repton, sought to make their landscapes seem as though they had evolved naturally over time rather than being newly formed by the hand of man, exactly what Olmsted achieved time and again in his work. Marvelous period renderings and photographs of Central Park in its early years—it took four decades for it to grow into the mature form we recognize today—are reproduced both in the new Library of America anthology as well as in Frederick Law Olmsted: Plans and Views of Public Parks, the magnificently illustrated companion to the definitive edition of the designer’s letters.

Olmsted’s ability to imagine how a barren stretch of urban wasteland could be turned into an idyllic glade that looks as if it had been there forever is demonstrated in several of his before-and-after sketches of Central Park. These and other visual documents make it clear how complicated that task was, with a host of now invisible infrastructural underpinnings that needed to be put into place—foundations for roads and paths, soil emendation and storm drainage, rerouting existing streams and ponds, dynamiting rock outcroppings—before any planting could begin.

The ninth segment of Olmsted’s correspondence (there will be one final illustrative volume in the series) culminates the heroic project initiated by Johns Hopkins University Press in 1972. If this program does not numerically surpass the forty-six volumes of Adams family papers issued by Harvard University Press since 1954, it nonetheless represents the most ambitious initiative of its kind on behalf of an American artist or designer in any medium, and deservedly so.

2.

Frederick Law Olmsted was born in 1822 to a successful Hartford merchant, who long remained his son’s financial mainstay, much as that other towering nineteenth-century design and social reformer William Morris was supported by a rich parent until he finally found his professional footing. Olmsted received an excellent secondary education at the Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, but poor health kept him from matriculating at Yale as planned. He then began a fitful decade of assorted occupations—from dry goods clerk to apprentice seaman on a China trade ship that sailed to Canton and back in 1843–1844—before his father staked him to a 125-acre farm on Staten Island. (The old Olmsted homestead still stands, in decrepit condition, near that outer borough’s busy Hylan Boulevard. It ought to be restored as befits an important cultural landmark.)

Throughout his life, Olmsted displayed an extraordinary ability to immerse himself in a new subject and fully master it. To better cultivate his property he studied the emergent applied science of progressive farming and land management enabled by recent discoveries in plant biology, industrial chemistry, and agricultural machinery. Yet the young would-be agronomist had many competing interests, and found that the relentless dawn-to-dark drudgery of farm work kept him from other pursuits. His watchful father saw the problem and admonished, “Your farm will require your close & undivided personal attention at all times & I hope no extraneous or unimportant matters…will take up your mind & time.”

However, important matters continued to distract the endlessly curious Fred, mainly journalism, a direct outgrowth of the acute powers of observation and thoughtful analysis so evident in his personal correspondence. Setting aside full-time farming, he served a two-year stint as an editor of Putnam’s Magazine, founded in New York in 1853 as an American-minded alternative to the Anglocentric literary journal Harper’s New Monthly Magazine. This job ended when Putnam’s foundered after the Panic of 1857, not the last time a nationwide financial crisis affected his career.

Olmsted’s extensive travels throughout the southern and southwestern United States during the 1850s to report on social and economic conditions for The New-York Daily Times produced sharply perceptive columns that were subsequently collected in three volumes, the first and best of which—A Journey in the Seaboard Slave States (1856)—remains a classic on a par with Alexis de Tocqueville’s endlessly cited American critique of a generation earlier. Though Olmsted was not an abolitionist, he supported the proposal that slave owners should be compensated for the value of their freed human chattel as the most equitable and practicable means of avoiding the looming conflict between North and South.2 That solution—which likely would have been far less costly than the Civil War in money, let alone blood—was of course never implemented.

The Cotton Kingdom, a compendium of his travel writings published in 1862 when the Civil War was in full swing, gave a harsh view of the region’s inhabitants, including their much-vaunted Southern hospitality:

The citizens of the cotton States…work little, and that little, badly; they earn little, they sell little; they buy little, and they have little—very little—of the common comforts and consolations of civilized life. Their destitution is not material only; it is intellectual and it is moral…. They were neither generous nor hospitable….

When hostilities broke out Olmsted had already completed his principal work on Central Park, and was thus able to transfer to the war effort the formidable executive skills he’d developed in marshaling the huge platoons of contractors and workmen for a logistically complex job. He became head of the US Sanitary Commission, an agency created after the incompetence of the US Army’s Medical Department became a national scandal. Long before the founding of the American Red Cross (1881) and the Department of Veterans Affairs (1930), the Sanitary Commission tried to ameliorate the appalling conditions inflicted on wounded and diseased soldiers. Of the 620,000 men who lost their lives in the Civil War, two thirds succumbed to illness, and Olmsted struggled to stem that toll in a period when the very basics of hygiene and sanitation were doubtful.

After the war he returned to finish his work on Central Park, and with Vaux began planning the sequel that some consider a more exquisite composition: their 585-acre Prospect Park of 1865–1873 in nearby Brooklyn. But Olmsted still kept a hand in the literary world as a financial backer of The Nation, the liberal political journal founded in 1865, to which he was an occasional contributor. Olmsted and Vaux dissolved their firm in 1872 after increasing disagreements, but the Panic of 1873 deterred Olmsted’s rapid rebound. When economic conditions improved he quickly reestablished himself with the help of two new partners, his nephew and adopted son John Charles Olmsted and his younger biological son, Frederick Law Olmsted Jr., who headed the firm until he retired in 1949. Olmsted Brothers finally went out of business in 1980.

By the first half of the 1890s—the period covered by the ninth volume of the Olmsted correspondence—the grand old man had become not merely a national but a continental eminence, as demand for his services impelled him to shuttle continually among far-flung projects from Maine to California and Michigan to Kentucky. Most experimental among them was his comprehensive planning of the Biltmore Estate in the North Carolina Blue Ridge Mountains for George Washington Vanderbilt II. The centerpiece of this 125,000-acre property is Richard Morris Hunt’s Biltmore House of 1889–1895, still the largest private residence in America, a French Renaissance Revival château like those favored by Vanderbilt’s plutocratic kin and kind on New York’s Fifth Avenue. Olmsted urged his client—who had run the Vanderbilt family farm on Staten Island, not far from Olmsted’s old property—to rise above the empty ostentation of Gilded Age display and instead turn the surrounding land into a model of modern sustainable forestry, an idea the multimillionaire admirably endorsed.

Not all of Olmsted’s late projects were so happy. His work at the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago fell victim to the rigid formality of the fair’s Beaux-Arts-inspired layout, in which monumental Classicizing buildings were surrounded by enormous lagoons that impeded easy circulation. One critic wrote that although Olmsted’s contribution was “unquestionably very fine to look at,” it was “totally unsuited for practical purposes.” The designer conceded as much, and wrote that the fair would have been much better without “perhaps a third of all that was exhibited and…an innumerable lot of trifling concession coops and shantees with slight regard to the landscape design.”

But this was a rare flub in an otherwise unbroken sequence of successes that gave many American cities their finest civic features, especially Boston’s dazzling “Emerald Necklace” park system (which comprises the Back Bay Fens, the Arnold Arboretum, and Wood Island Park, among other things) and the refashioning of Buffalo’s topography through parkways, squares, and lakefront improvements. In 1895, the seventy-three-year-old Olmsted began to notice short-term memory lapses, and though his letters from that year show no sign of cognitive impairment, his sons eased him out of the family business. Before long he had full-blown dementia, and he lived out the last five years of his life in a cottage at the McLean Hospital near Boston, where he died in 1903 amid grounds he had laid out long before.

Olmsted’s status as a national figure was confirmed by the invitation in 1874 to landscape the grounds of the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C., a tricky assignment that gave this sprawling and oddly proportioned structure—erected in fits and starts to the designs of several different architects throughout the first half of the nineteenth century—a softening frame of majestic trees and shrubberies worthy of its grandeur. This deeply symbolic scheme also paid indirect homage to a national heritage of unparalleled natural splendor, which Olmsted, more than anyone save the pioneering conservationists George Perkins Marsh and John Muir, identified, celebrated, enhanced, extended, and preserved. Yet even Olmsted, for all his uncanny foresight about how his parks would function in a future beyond his possible imagination, could never have predicted how instructive they would be in today’s polarized America, so different from the egalitarian society those unifying designs vigorously promoted.

This Issue

November 5, 2015

A Conversation in Iowa

The Man Who Flew Like a Bird

-

1

See my “Up in the Park,” The New York Review, August 13, 2009, and “Higher and Higher,” The New York Review, November 24, 2011. ↩

-

2

See the letter from Laura Wood Roper and reply by C. Vann Woodward, “Fair Play for Olmsted,” The New York Review, June 13, 1974. ↩