I had told Jann Wenner of Rolling Stone that I would cover the Patty Hearst trial, and this pushed me into examining my thoughts about California. Some of my notes from the time follow here. I never wrote the piece about the Hearst trial, but I went to San Francisco in 1976 while it was going on and tried to report it. And I got quite involved in uncovering my own mixed emotions. This didn’t lead to my writing the piece, but eventually it led to—years later—Where I Was From (2003).

When I was there for the trial, I stayed at the Mark. And from the Mark, you could look into the Hearst apartment. So I would sit in my room and imagine Patty Hearst listening to Carousel. I had read that she would sit in her room and listen to it. I thought the trial had some meaning for me—because I was from California. This didn’t turn out to be true.

—March 23, 2016

The first time I was ever on an airplane was in 1955 and flights had names. This one was “The Golden Gate,” American Airlines. Serving Transcontinental Travelers between San Francisco and New York. A week before, twenty-one years old, I had been moping around Berkeley in my sneakers and green raincoat and now I was a Transcontinental Traveler, Lunching Aloft on Beltsville Roast Turkey with Dressing and Giblet Sauce. I believed in Dark Cottons. I believed in Small Hats and White Gloves. I believed that transcontinental travelers did not wear white shoes in the City. The next summer I went back on “The New Yorker,” United Airlines, and had a Martini-on-the-Rocks and Stuffed Celery au Roquefort over the Rockies.

The image of the Golden Gate is very strong in my mind. As unifying images go this one is particularly vivid.

At the Sacramento Union I learned that Eldorado County and Eldorado City are so spelled but that regular usage of El Dorado is two words; to UPPER CASE Camellia Week, the Central Valley, Sacramento Irrigation District, Liberator bombers and Superfortresses, the Follies Bergere [sic], the Central Valley Project, and “such nicknames as Death Row, Krauts, or Jerries for Germans, Doughboys, Leathernecks, Devildogs.”

Arden School class prophecy:

In Carnegie Hall we find Shirley Long

Up on the stage singing a song.

Acting in pictures is Arthur Raney’s job,

And he is often followed by a great mob.

As a model Yavette Smith has achieved fame,

Using “Bubbles” as her nickname…

We find Janet Haight working hard as a missionary,

Smart she is and uses a dictionary…

We find Joan Didion as a White House resident

Now being the first woman president.

Looking through the evidence I find what seems to me now (or rather seemed to me then) an entirely spurious aura of social success and achievement. I seem to have gotten my name in the paper rather a lot. I seem to have belonged to what were in context the “right” clubs. I seem to have been rewarded, out of all proportion to my generally undistinguished academic record, with an incommensurate number of prizes and scholarships (merit scholarships only: I did not qualify for need) and recommendations and special attention and very probably the envy and admiration of at least certain of my peers. Curiously I only remember failing, failures and slights and refusals.

I seem to have gone to dances and been photographed in pretty dresses, and also as a pom-pom girl. I seemed to have been a bridesmaid rather a lot. I seem always to have been “the editor” or the “president.”

I believed that I would always go to teas.

This is not about Patricia Hearst. It is about me and the peculiar vacuum in which I grew up, a vacuum in which the Hearsts could be quite literally king of the hill.

I have never known deprivation.

How High the Moon, Les Paul and Mary Ford. High Noon.

I have lived most of my life under misapprehensions of one kind or another. Until I was in college I believed that my father was “poor,” that we had no money, that pennies mattered. I recall being surprised the first time my small brother ordered a dime rather than a nickel ice cream cone and no one seemed to mind.

My grandmother, who was in fact poor, spent money: the Lilly Daché and Mr. John hats, the vicuña coats, the hand-milled soap and the $60-an-ounce perfume were to her the necessities of life. When I was about to be sixteen she asked me what I wanted for my birthday and I made up a list (an Ultra-Violet lipstick, some other things), meaning for her to pick one item and surprise me: she bought the list. She gave me my first grown-up dress, a silk jersey dress printed with pale blue flowers and jersey petals around the neckline. It came from the Bon Marché in Sacramento and I knew what it cost ($60) because I had seen it advertised in the paper. I see myself making many of the same choices for my daughter.

Advertisement

At the center of this story there is a terrible secret, a kernel of cyanide, and the secret is that the story doesn’t matter, doesn’t make any difference, doesn’t figure. The snow still falls in the Sierra. The Pacific still trembles in its bowl. The great tectonic plates strain against each other while we sleep and wake. Rattlers in the dry grass. Sharks beneath the Golden Gate. In the South they are convinced that they have bloodied their place with history. In the West we do not believe that anything we do can bloody the land, or change it, or touch it.

How could it have come to this.

I am trying to place myself in history.

I have been looking all my life for history and have yet to find it.

The resolutely “colorful,” anecdotal quality of San Francisco history. “Characters” abound. It puts one off.

In the South they are convinced that they are capable of having bloodied their land with history. In the West we lack this conviction.

Beautiful country burn again.

The sense of not being up to the landscape.

There in the Ceremonial Courtroom a secular mass was being offered.

I see now that the life I was raised to admire was infinitely romantic. The clothes chosen for me had a strong element of the Pre-Raphaelite, the medieval. Muted greens and ivories. Dusty roses. (Other people wore powder blue, red, white, navy, forest green, and Black Watch plaid. I thought of them as “conventional,” but I envied them secretly. I was doomed to unconventionality.) Our houses were also darker than other people’s, and we favored, as a definite preference, copper and brass that had darkened and greened. We also let our silver darken carefully in all the engraved places, to “bring out the pattern.” To this day I am disturbed by highly polished silver. It looks “too new.”

This predilection for “the old” carried into all areas of our domestic life: dried flowers were seen to have a more lasting charm than fresh, prints should be faded, a wallpaper should be streaked by the sun before it looks right. As decorative touches went our highest moment was the acquisition of a house (we, the family, moved into it in 1951 at 22nd and T in Sacramento) in which the curtains had not been changed since 1907. Our favorite curtains in this house were gold silk organza on a high window on the stairwell. They hung almost two stories, billowed iridescently with every breath of air, and crumbled at the touch. To our extreme disapproval, Genevieve Didion our grandmother replaced these curtains when she moved into the house in the late 1950s. I think of those curtains still, and so does my mother. (domestic design)

Oriental leanings. The little ebony chests, the dishes. Maybeck houses. Mists. The individual raised to mystic level, mysticism with no religious basis.

When I read Gertrude Atherton* I recognize the territory of the subtext. The Assemblies unattended, the plantations abandoned—in the novels as in the dreamtime—because of high and noble convictions about slavery. Maybe they had convictions, maybe they did not, but they had also worked out the life of the farm. In the novels as well as the autobiography of Mrs. Atherton we see a provincial caste system at its most malign. The pride in “perfect taste,” in “simple frocks.”

In the autobiography, page 72, note Mrs. Atherton cutting snakes in two with an axe.

When I read Gertrude Atherton I think not only of myself but of Patricia Hearst, listening to Carousel in her room on California Street.

The details of the Atherton life appear in the Atherton fiction, or the details of the fiction appear in the autobiography: it is difficult to say which is the correct construction. The beds of Parma violets at the Atherton house dissolve effortlessly into the beds of Parma violets at Maria Ballinger-Groome Abbott’s house in Atherton’s The Sisters-in-Law. Gertrude’s mother had her three-day “blues,” as did one of the characters in Sleeping Fires. Were there Parma violets at the Atherton house? Did Gertrude’s mother have three-day blues?

When I contrast the houses in which I was raised, in California, to admire, with the houses my husband was raised, in Connecticut, to admire, I am astonished that we should have ever built a house together.

Climbing Mount Tamalpais in Marin County, a mystical ideal. I never did it, but I did walk across the Golden Gate Bridge, wearing my first pair of high-heeled shoes, bronze kid De Liso Debs pumps with three-inch heels. Crossing the Gate was, like climbing Tamalpais, an ideal.

Advertisement

Corte Madera. Head cheese. Eating apricots and plums on the rocks at Stinson Beach.

Until I read Gertrude Atherton I had never seen the phrase “South of Market” used exactly the way my grandmother, my mother, and I had always used it. Edmund G. “Pat” Brown was South of Market.

My father and brother call it “Cal” (i.e., the University of California at Berkeley). They were fraternity men, my father a Chi Phi, my brother a Phi Gamma Delta. As a matter of fact I belonged to a house too, Delta Delta Delta, but I lived in that house for only two of the four years I spent at Berkeley.

There used to be a point I liked on the Malibu Canyon road between the San Fernando Valley and the Pacific Ocean, a point from which one could see what was always called “the Fox sky.” Twentieth Century Fox had a ranch back in the hills there, not a working ranch but several thousand acres on which westerns were shot, and “the Fox sky” was simply that: the Fox sky, the giant Fox sky scrim, the big-country backdrop.

By the time I started going to Hawaii the Royal Hawaiian was no longer the “best” hotel in Honolulu, nor was Honolulu the “smart” place to vacation in Hawaii, but Honolulu and the Royal Hawaiian had a glamour for California children who grew up as I did. Little girls in Sacramento were brought raffia grass skirts by returning godmothers. They were taught “Aloha Oe” at Girl Scout meetings, and to believe that their clumsiness would be resolved via mastery of the hula. For dances, later, they wanted leis, and, if not leis, bracelets of tiny orchids, “flown in” from Honolulu. I recall “flown in” as a common phrase of my adolescence in Sacramento, just “flown in,” the point of origin being unspoken, and implicit. The “luau,” locally construed as a barbecue with leis, was a favored entertainment. The “lanai” replaced the sun porch in local domestic architecture. The romance of all things Hawaiian colored my California childhood, and the Royal Hawaiian seemed to stand on Waikiki as tangible evidence that this California childhood had in fact occurred.

I have had on my desk since 1974 a photograph that I cut from a magazine just after Patricia Campbell Hearst was kidnapped from her Berkeley apartment. This photograph appeared quite often around that time, always credited to Wide World, and it shows Patricia Hearst and her father and one of her sisters at a party at the Burlingame Country Club. In this photograph it is six or seven months before the kidnapping and the three Hearsts are smiling for the camera, Patricia, Anne, and Randolph. The father is casual but festive—light coat, dark shirt, no tie; the daughters flank him in long flowered dresses. They are all wearing leis, father and daughters alike, leis quite clearly “flown in” for the evening. Randolph Hearst wears two leis, one of maile leaves and the other of orchids strung in the tight design the lei-makers call “maunaloa.” The daughters each wear pikake leis, the rarest and most expensive kind of leis, strand after strand of tiny Arabian jasmine buds strung like ivory beads.

Sometimes I have wanted to know what my grandmother’s sister, May Daly, screamed the day they took her to the hospital, for it concerned me, she had fixed on me, sixteen, as the source of the terror she sensed, but I have refrained from asking. In the long run it is better not to know. Similarly, I do not know whether my brother and I said certain things to each other at three or four one Christmas morning or whether I dreamed it, and have not asked.

We are hoping to spend part of every summer together, at Lake Tahoe. We are hoping to reinvent our lives, or I am.

The San Francisco Social Register. When did San Francisco become a city with a Social Register. How did this come about? The social ambitiousness of San Francisco, the way it has always admired titles, even bogus titles.

All my life I have been reading these names and I have never known who they were or are. Who, for example, is Lita Vietor?

C. Vann Woodward: “Every self-conscious group of any size fabricates myths about its past: about its origins, its mission, its righteousness, its benevolence, its general superiority.” This has not been exactly true in San Francisco.

Some Women:

Gertrude Atherton

Julia Morgan

Lilly Coit

Jessica Peixotto

Dolly Fritz/Lita Vietor/McMasters/Cope

Phoebe Apperson Hearst

Patricia Campbell Hearst

Jesse Benton Fremont

Part of it is simply what looks right to the eye, sounds right to the ear. I am at home in the West. The hills of the coastal ranges look “right” to me, the particular flat expanse of the Central Valley comforts my eye. The place names have the ring of real places to me. I can pronounce the names of the rivers, and recognize the common trees and snakes. I am easy here in a way that I am not easy in other places.

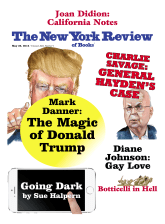

This Issue

May 26, 2016

Who Was David Hume?

Botticelli in Hell

-

*

Gertrude Atherton (1857–1948) was born in San Francisco and became a prolific and at times controversial writer of novels, short stories, essays, and articles on subjects that included feminism, politics, and war. Many of her novels are set in California. —The Editors ↩