1.

Few things are more satisfying in the arts than unjustly forgotten figures at last accorded a rightful place in the canon, as has happened in recent decades with such neglected but worthy twentieth-century architects as the Slovenian Jože Plečnik, the Austrian Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky, the Austrian-Swedish Josef Frank, and the Italian-Brazilian Lina Bo Bardi, among others. Then there are the perennially celebrated artists who are so important that they must be presented anew to each successive generation, a daunting task for museums, especially encyclopedic ones that are expected to revisit the major masters over and over again while finding fresh reasons for their relevance.

Barry Bergdoll, the Columbia professor who served as the Museum of Modern Art’s chief curator of architecture and design from 2007 to 2013, continues to do exhibitions for the museum, and his latest, “Frank Lloyd Wright at 150: Unpacking the Archive” (which he organized with Jennifer Gray, a project research assistant at MoMA), was a more hazardous proposition than its universally beloved subject might indicate. Despite the seeming effortlessness with which the Modern has spun out popular Picasso and Matisse shows decade after decade, Bergdoll wanted to avoid rehashing its 1994 Wright retrospective or repeating material covered in more specialized exhibitions on the architect held in New York at the Whitney in 1997 and the Guggenheim in 2009.

He decided instead to organize this sesquicentennial tribute around a mere twelve projects, including rarely discussed unexecuted designs such as Wright’s Depression-era plans for a self-sufficient agricultural community and his postwar scheme for the world’s tallest skyscraper. These and others are illuminated by some 450 drawings, documents, photographs, models, and architectural fragments selected from the mountain of objects obtained by MoMA and Columbia’s Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library when they took possession of the architect’s archives from the economically troubled Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation in 2012. Financial details of the arrangement have not been revealed, but it has been rumored that a transfer of money was involved, on terms said to be very favorable for the acquiring institutions.

The sheer numbers involved in this transcontinental move are staggering: 55,000 drawings, 300,000 sheets of correspondence, 125,000 photographs, 2,700 manuscripts, and a panoply of miscellanea including architectural details, working and presentation models, documentary films, and home movies, all of which had been moldering away under less-than-ideal conditions at Taliesin in Spring Green, Wisconsin, and Taliesin West, the foundation’s headquarters in Scottsdale, Arizona. (The archive will now be stored on the Columbia campus, with conservation done at the museum.)

There is a piquant irony to the final disposition of Wright’s architectural estate, for this supreme egotist never forgave MoMA for what he deemed the slighting treatment he received from Philip Johnson and Henry-Russell Hitchcock in their epochal “Modern Architecture: International Exhibition” of 1932, which he felt should have revolved around him, his characteristic worldview. Tellingly enough, the current show turns out to be the eleventh MoMA exhibition in which Wright has been included, and although some of those were relatively minor mountings devoted to single projects, he has tallied more cumulative gallery time there than any other architect (even though Ludwig Mies van der Rohe has been given three solo retrospectives, another MoMA architectural record).

To arrive at the dozen projects featured in the exhibition, Bergdoll asked each member of a team of scholars to select a single work from the archive—the less familiar the better—and discuss it in depth. Although MoMA officials have proudly stressed that they engaged a younger generation of untapped talent instead of what Bergdoll has called “the usual suspects,” only two of the catalog’s sixteen authors are in their thirties, with more than half older than fifty, and five in their sixties and seventies.

These demographics seem to confirm what academicians warned of decades ago: that the restrictive control of the master’s archives for a quarter-century after his death in 1959 by his widow, Olgivanna (who died in 1985), would set back Wright studies for a full generation, if not longer. Dissertation advisers prudently steered doctoral candidates away from Wright topics because of the extortionate research and reproduction fees demanded by his foundation, as well as the editorial approval it demanded for publications that used material from the Taliesin archive. The rise of poststructuralist criticism further eroded younger scholars’ interest in an architect whose uniquely personal approach to architecture had little to do with the period’s fascination with literary theory.

2.

The detailed attention given in the current exhibition to discrete aspects of Wright’s output rather than its broad outlines risked a certain unevenness, and lesser-known work by great artists is often obscure for good reason. Happily, despite its many participants, “Wright at 150” coheres better than one had expected. Helpful in that respect is its layout around a spacious central gallery devoted to highlights from the architect’s career not covered elsewhere in the show, while the more specialized themes are arranged in separate rooms around it.

Advertisement

This introductory “spine” is hung with renderings of many projects well known to the public, including Unity Temple of 1905–1908 in Oak Park, Illinois, an inward-turning concrete monolith that reopened in June after a two-year, $25 million restoration; Fallingwater of 1934–1938 in Bear Run, Pennsylvania, with its breathtakingly cantilevered balconies perched above a woodland cascade; the Johnson Wax Administration Building of 1936–1939 in Racine, Wisconsin, a streamlined reconception of the corporate workplace as a light-filled forest grove; and Taliesin West of 1936–1959, the architect’s mirage-like desert home and studio.

Regrettably, the catalog accompanying the show is so spottily edited and annoyingly designed that one yearns for the firm hand of MoMA’s longtime editorial director, Harriet Bee, now retired. There are many misspellings and misusages in addition to confusing designations of illustrations, page numbers positioned in gutters, and no index. The publication for the museum’s 1994 Wright show remains altogether a far superior reference. However, three of the new essays are of exceptional quality.

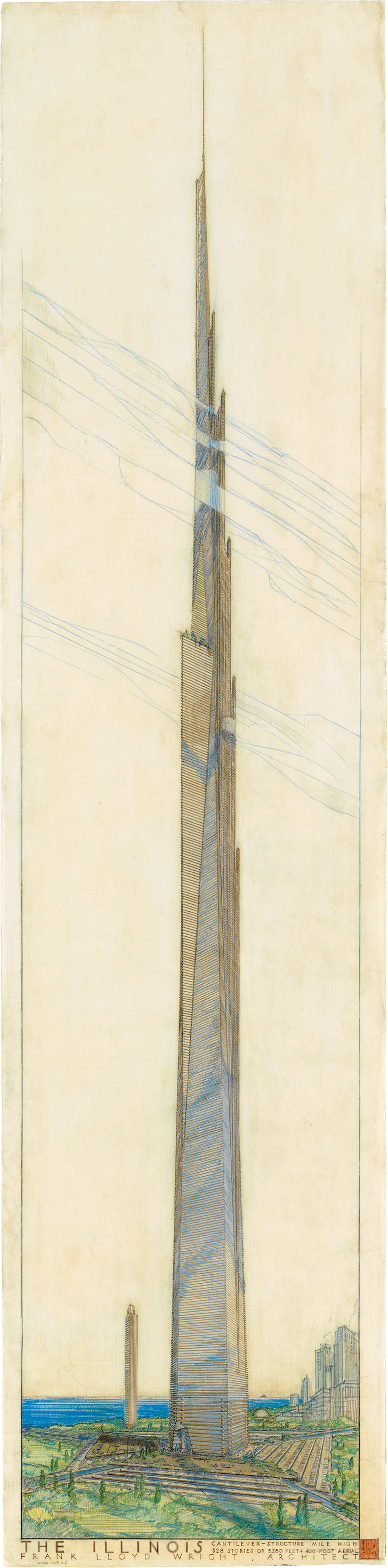

Bergdoll’s investigation of Wright’s hypothetical Mile-High Illinois skyscraper of 1956—a 528-story tower intended for an unspecified site in Chicago and nearly twice as high as the tallest building executed since then—makes one wonder why, given the postmillennial mania for super-tall, super-thin engineering, it has taken until now for this stupendous oddity, more publicity stunt than serious proposal, to be reexamined so thoughtfully. Bergdoll interprets the architect’s eight-foot-tall, foot-and-a-half-wide presentation drawing, which resembles some ancient scroll opened to its full height, as a revealing artistic last will and testament prepared for posterity three years before his death at ninety-one. On it the needle-like visionary structure extends from the bottom—where its “tap-root” foundation burrows into the earth as deep as the Empire State Building is tall—to little over the halfway mark, with lengthy autobiographical inscriptions occupying the uppermost portions. (Another of Wright’s drawings of the skyscraper appears on this page.)

The two other most engrossing schemes selected for the show emphasize Wright’s long engagement with several of the most progressive currents in American society. This began in infancy when his mother, Anna Lloyd Jones Wright, exposed him to the innovative pedagogical practices of the German education reformer Friedrich Fröbel; continued throughout his youth with exposure to the preaching of his renowned social activist and pacifist uncle, the Unitarian minister Jenkin Lloyd Jones; included immersion in the early twentieth century’s most advanced feminist ideas, which were shared by his freethinking companion Mamah Borthwick; and extended to ecological preservation, as signified by his being made an honorary member of the Friends of Our Native Landscape, an early environmental advocacy group founded in 1913. (Wright’s subsequent support for the isolationist America First Committee between the outbreak of World War II in Europe and Pearl Harbor is often seen as a conservative retreat from those formative principles, but he always insisted that his opposition to US involvement in foreign conflicts was solely pacifist, not political.)

Although Wright’s principal response to the Great Depression is commonly seen as his founding in 1932 of the Taliesin Fellowship—the idealistic work-study commune that served both as an architecture school and his architectural office—between the world wars he accepted two commissions that displayed his ability to imaginatively rethink social issues. The Little Farms Unit project of 1932–1933 was intended for a back-to-the-land initiative on Long Island that would have fostered small regional agriculture as a means of making people self-sufficient at a time of widespread economic collapse and catastrophic unemployment. The low-rise, streamlined, multipurpose food-processing and marketing facility that Wright devised as a replicable prototype for this experiment in modern subsistence farming was underwritten by the businessman Walter V. Davidson.

A former advertising executive for the Larkin Soap Company, whose monumental Buffalo headquarters of 1903–1906 Wright designed, Davidson commissioned a Prairie House from the architect in 1908. Decades later he returned to Wright to help realize this utopian rural rescue mission, which never moved beyond the planning stage despite Davidson’s obsessive projections. Wright’s sleekly Modernist concept looks more like the contemporaneous work of the Dutch De Stijl architect J.J.P. Oud, and both the jaunty model unearthed for the show and the inspiring story behind it—recounted in a catalog essay by the MoMA curator Juliet Kinchin—make this a major rediscovery.

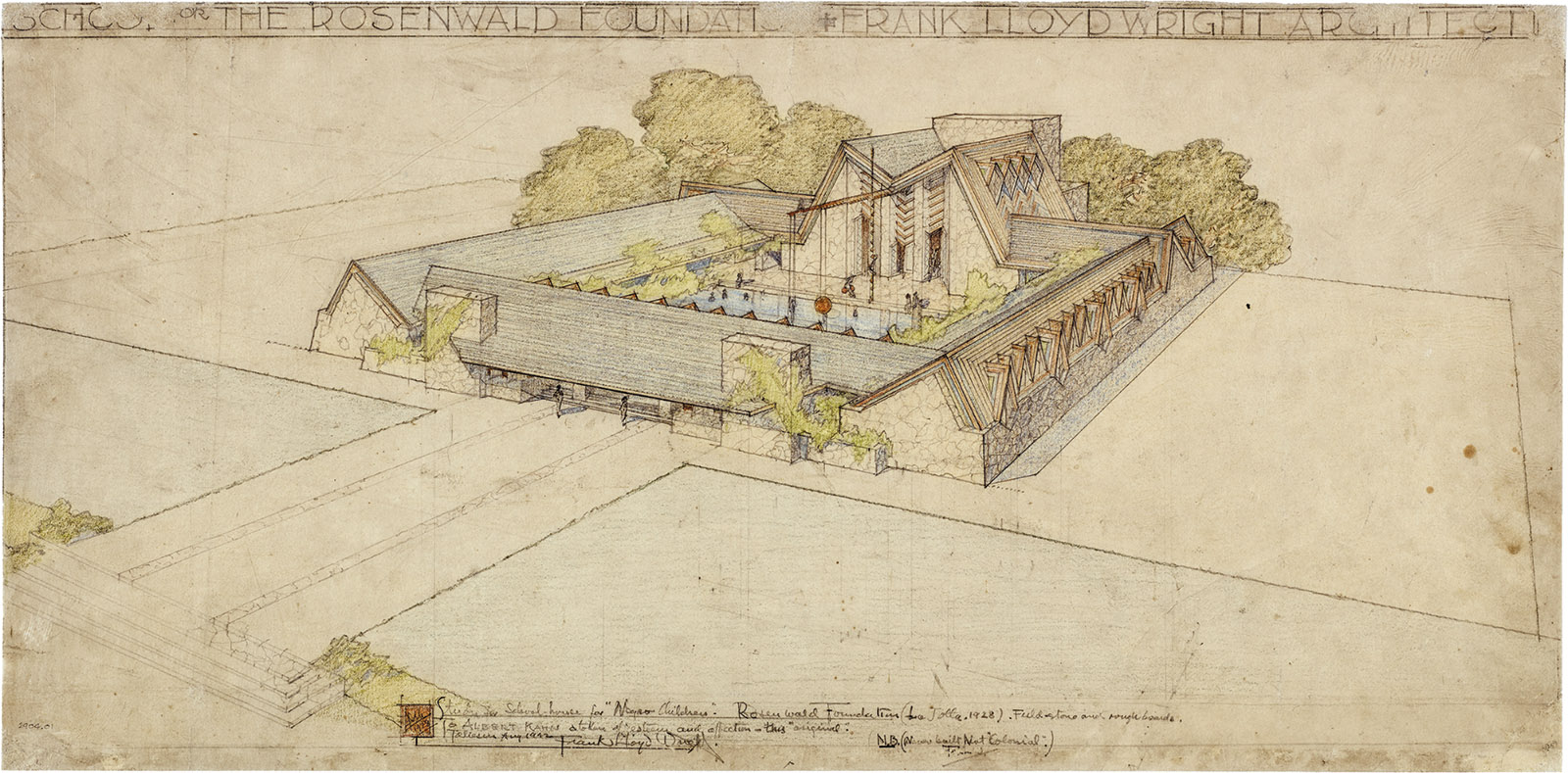

Of equal significance as socially motivated design is Wright’s unrealized Rosenwald School of 1928 for the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute in Virginia. Sponsored by the Chicago philanthropist Julius Rosenwald—president and later chairman of Sears, Roebuck & Company, then the world’s largest catalog retailer—the project was meant to give architectural distinction to a charitable vocational education program dedicated to freeing poor rural blacks from an intractable cycle of poverty. Wright’s scheme departed from the neo-Colonial daintiness of previous designs that had been pursued under the widely admired “Hampton Ideal,” and proposed a cloister-like unit dominated by a dramatic central structure, with twin-peaked roofs as if two A-frame houses had been laterally conjoined, quite unlike the earth-hugging structures generally associated with him. In her probing analysis of this long-lost scheme, Mabel O. Wilson, who teaches at the Columbia architecture school, does not rationalize the paternalistic undertone of racial condescension inescapable in Wright’s hope that through his design “the Darkies would have something that belonged to them. Something exterior of their own lively interior color and charm.”

Advertisement

Indeed, to say that Wright—born just two years after the death of Abraham Lincoln (and originally named Frank Lincoln Wright in his memory)—was simply echoing the prevalent racial attitudes of his time might seem like special pleading. But others who knew him well, including his longtime official photographer, the Mexican-American Pedro E. Guerrero, himself subjected to bigotry in the pre-war Southwest, have averred that amid the racism of mid-twentieth-century America, Wright was at heart among the least prejudiced men they had ever known.

3.

Although Wright was a born draftsman—as proven by his intricate yet ethereal 1892 drawing of a bronze gate for the Wainwright Tomb in St. Louis, designed by his boss Louis Sullivan and now on view in the MoMA show—from the very start of his independent practice the following year he hired talented renderers to create presentation drawings of his projects. The current exhibition goes to great lengths to stress this fact by identifying specific hands at various points in his career, especially one of Wright’s earliest collaborators, Marion Mahony. Like Wright, Mahony was entranced by the woodblock prints of Japanese masters that had become all the rage among Western artists during the second half of the nineteenth century.

Her delicately toned rendering of a lesser-known Prairie House—his DeRhodes residence of 1906 in South Bend, Indiana—mimics the flattened planes, strong outlines, and suggestive voids typical of the Ukiyo-e style. Lest this point be lost on us, beneath her signature she added, “After FLLW and Hiroshige.” Wright, who had a deeply acquisitive streak that impelled him to buy beautiful things even when he could not pay his grocer’s bills, amassed such a large hoard of Japanese graphics that like many other compulsive but impecunious collectors he perforce became a dealer both to balance his books and to further feed his habit.

In 1913, when Wright’s architectural practice had come to a veritable halt because of the public outrage he caused by leaving the mother of his six children and setting up housekeeping with Mamah Borthwick, a client’s wife, he traveled to Japan with the express purpose of raising cash by buying and selling prints. Bankrolled by two rich Boston aesthetes, the Spaulding brothers, the out-of-work architect, as he later wrote,

established a considerable buying power and anything available in the ordinary channels came first to me…until I had spent about one hundred and twenty-five thousand Spaulding dollars for about a million dollars’ worth of prints.

Proof of Wright’s discriminating eye was evident in a small but exquisite recent exhibition, “The Formation of the Japanese Print Collection at the Art Institute of Chicago: Frank Lloyd Wright and the Prairie School,” at the museum where the architect arranged a show with some of the same pieces in 1908, not least to create a local market for his lucrative sideline.

Because of further personal scandals (the murder of Borthwick and her children at Taliesin in 1914; a sordid divorce from his second wife; and the birth of a final child, out of wedlock) as well as changing architectural tastes—which encompassed the demise of the Arts and Crafts Movement, a resurgent Classical revival in the US, and the emergence of more radical forms of Modernism in Europe—Wright saw his job prospects go dormant for a crucial decade in midlife when architects customarily receive their most important commissions. It was only the sheer force of his titanic will and capacity to constantly readapt his protean talents to new conditions—for example by taking up the new technique of concrete-block construction in Southern California during the 1920s and devising affordable “Usonian” houses for middle-class Americans in the 1930s—that gave him a second career during his final quarter-century, wholly different from but comparable in inventiveness to his Prairie School period of 1900–1914.

Once he at long last shifted into an unbroken two-decade professional upswing after the late 1930s, he spent even more time exploiting his public persona. The degree to which he became America’s most recognizable architect between Stanford White and Philip Johnson through his skillful manipulation of mass media—two film clips now on view at MoMA record his disarmingly deft star turns on 1950s TV talk and quiz shows, with deadpan timing worthy of Jack Benny—speaks to his acute understanding of celebrity culture in this country. Yet for all his serial self-reinventions, Wright never lost sight of his core mission of reshaping architecture into a wholly consistent reflection of democratic American values as he understood them.

The care, audacity, and originality with which Wright orchestrated the public presentation of his revolutionary architecture from start to finish—thereby finessing its positive critical reception—is laid out with exceptional thoroughness in Kathryn Smith’s Wright on Exhibit: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Architectural Exhibitions. Despite its apparently circumscribed subject matter, the book widens into an intriguing treatise on career development, and is so illuminatingly detailed that it gives a richer portrait of Wright than many full-length biographies. It would be hard, for example, to find a clearer, more concise, and yet poetic summation of Wright’s quantum leap at the dawn of the twentieth century than Smith’s description of the typical Prairie House and Wright’s concomitant introduction of the open plan, a pivotal moment in the history of modern architecture:

A major conceptual breakthrough that he made early on was the realization that mechanical heating made it no longer necessary to close rooms off from each other to conserve heat. This discovery led to the open plan in public spaces—for instance, where the living room opened to the dining room on a diagonal—while maintaining compartmentalized rooms for services. With the hearth no longer used as the major source of heat, Wright was free to use it as a freestanding vertical plane in space.

The other major advance represented by the Prairie House was the rejection of the wall as the traditional solid barrier between inside and outside…. He broke the wall down into a series of elements such as piers, flat planes, and window bands—all geometrically organized by dark wood strips. The wall was now defined as an enclosure of space. Windows were no longer holes punched through a mass, but a light screen filtering sunlight into the interior. The movement out toward the landscape was amplified by the addition of porches, terraces, flower boxes, and planter urns….

The straight line of the horizon became the low sheltering roof, trees and flowers were abstracted as geometric patterns in the art glass windows, and leaves contributed their autumnal palette to the plaster surfaces.

4.

Confirmation of Wright’s incomparable popularity today is inescapable when one goes to any of the more than 140 buildings by him open to visitors in the United States and Japan (about one third of his total executed output). Those landmarks are the subject of Wright Sites: A Guide to Frank Lloyd Wright Public Places, the essential vademecum first published in 1991 and now reissued in a revised and expanded fourth edition to accommodate several more buildings that have begun admitting people in recent years. In contrast to most modern architectural venues, his buildings attract a broad cross-section of nonspecialists who may not even be regular museum visitors. Clearly something about Wright speaks to the general public in a way that the work of no other architect does.

Drawing the highest attendance figures of any of the master’s buildings is the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum of 1943–1959 in New York, with 873,402 visitors in 2016 reported by The Art Newspaper. You would thus suppose there are numerous books on this endlessly celebrated structure, but most writing on it has been confined to essays in more general publications on Wright’s work. That lacuna likely prompted The Guggenheim: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Iconoclastic Masterpiece, by the architectural historian Francesco Dal Co. But the relatively brief main text is hindered by an overly elaborated account of the Guggenheim’s complex structural engineering, which all but the most technically attuned professionals will likely find taxing. (Those seeking a clearer account of how this eccentric masterpiece came into being should consult The Guggenheim: Frank Lloyd Wright and the Making of the Modern Museum, an excellent collection of essays published in 2009.)

The most curious publication to appear in this sesquicentennial year is The Life of Olgivanna Lloyd Wright, a biography of the architect’s third and last wife, whom he married in 1928. It was compiled by Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer, a former Wright apprentice who went on to become the longtime director of the architect’s archives, and Maxine Fawcett-Yeske, a musicologist who unearthed a partial and unpublished autobiographical memoir by Mrs. Wright while at Taliesin West researching her musical compositions, an endeavor she took up after her husband’s death. To flesh out this incomplete story, Pfeiffer and Fawcett-Yeske augmented it with large excerpts from her several autobiographical books, and the result is most tactfully characterized by the coeditors’ own description of it as a “labor of love.”

During the dark years of Wright scholarship before Olgivanna Wright’s death, Pfeiffer worked valiantly behind the scenes to be of as much help as possible to writers—this one included—without incurring the wrath of the volatile woman he had come to regard as a surrogate mother. He arrived at the Taliesin Fellowship as a worshipful nineteen-year-old, and like the outlooks of most of the other young people drawn to the master’s presence, Pfeiffer’s was formed by the powerful communal spirit of the organization, which hovered somewhere between that of a supportive extended family, an intrigue-ridden royal court, and a quasi-religious cult. Mrs. Wright vigorously fomented this Byzantine atmosphere, intervened in the sex lives of the Taliesin apprentices as a matter of right, and let no detail of the Fellowship escape her panoptic control.

Much of Olgivanna Wright’s reminiscences deal with how she and her husband coped in his very last years with the demands, distractions, and delights of his cultural stardom. Contrary to her dour image as his ferocious protector, the chatelaine of Taliesin was not without humor, some of it unintentional, as is evident in her account of the architect’s attempt to persuade Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas to visit the couple at Taliesin after a reading given by Stein in Madison, Wisconsin. Though his northern headquarters was within easy driving distance, the Parisian ladies demurred. Mrs. Wright recalled:

[Stein] smiled while Alice Toklas kept repeating in Steinian style, “No, thank you. Thank you, no. We are flying to Minneapolis tonight. We love to fly to Minneapolis.”

Frank still held to his faith and pursued his course: “Taliesin is beautiful,” he said. “We have a group of talented young people who will be interested to meet you. They can drive you to Minneapolis.”

Miss Toklas answered, “Oh, but we love to fly.”

Then Gertrude Stein spoke, “We do really. Really we do like to fly. We always fly everywhere because we like to fly.”

The fearsome Olgivanna Wright could not, however, resist one final dig at that odd couple. As she and her husband walked away in defeat she told him, “I knew you were going to fail the minute I laid my eyes on them!”

In Lewis Mumford’s warmly sympathetic two-part New Yorker review of Wright’s 1953 Guggenheim retrospective, the critic referred to him as the “Fujiyama of Architecture,” an apt metaphor for a master builder who seemed as ubiquitous and eternal as the snow-capped Japanese peak. Yet looking back once again on Wright’s achievement and the continued interest he inspires a century and a half after his birth, a more appropriate analogy for him in the natural world might be the giant sequoia. Wright was the hardy evergreen of architecture who towered high above his contemporaries, and although no man can begin to approach the three-and-a-half-millennium lifespan of the oldest giant sequoia, who could doubt that this perennially life-affirming artist is anything but a phenomenon for the ages?