Lebanon is a tiny country, with a population of around six million; it could fit neatly between Philadelphia and Danbury, Connecticut. It has survived many crises over the past several decades: a brutal civil war from 1975 to 1990 that left 100,000 dead, a string of political assassinations since 2004 whose perpetrators have gone unpunished, and occupations by Israel and Syria. But Lebanon’s resilience is fraying. Its infrastructure is badly damaged and unemployment is high. It is also struggling to accommodate a large refugee population—500,000 Palestinians, many descended from those who fled the 1948 Arab-Israeli war, and nearly 1.5 million Syrians, a majority of them Sunni Muslims.

Most of the Syrian refugees I met in Lebanon do not want to be there—or in Turkey, Jordan, Iraq, or Egypt. They are fleeing intense fighting, ethnic cleansing, starvation, chemical attacks, and Russian air strikes that devastated Aleppo and other rebel-held areas. It is clear that they are not welcome in Lebanon, where they are increasingly seen as disrupting the country’s delicate sectarian balance among Shia Muslims, Druze, and Christians and as vulnerable to Islamist radicalization.

Lebanon’s most recent crisis was the sudden resignation of Prime Minister Saad Hariri on November 4 during a visit to Saudi Arabia. His announcement, in which he explained that he was afraid for his life, surprised even his closest advisers and rattled the country. He has since returned to Lebanon and has suspended his resignation. Hariri’s father, Rafik, a former prime minister and a prominent Sunni businessman, was assassinated in 2005, along with twenty-two others, when explosives hidden in a van were detonated as his motorcade drove near the St. Georges Hotel in Beirut. After a painful inquiry, the UN determined that the assassination was likely committed by members of Hezbollah with Syrian planning and logistical support. Hezbollah is the Shia political party and militant organization funded by Iran and Syria. Hariri’s death was followed by a series of sectarian murders of other anti-Syrian politicians, compounding the long-standing frustration with Lebanon’s failure to bring his killers to justice.

Hezbollah, which backed President Bashar al-Assad in the Syrian war, has attained so much power in Lebanon that it is considered a state within a state. It holds sway in parliament and is able to infiltrate Lebanese military intelligence. Meanwhile, Saudi Arabia, the regional Sunni giant emboldened by the Trump administration’s seal of approval, has a stake in keeping Sunnis prominent in the Lebanese government.

These rising tensions are part of a much larger conflict. Saudi Arabia and Iran, the regional Shia giant, are fighting proxy wars for influence in the Middle East. The bloodiest battlefield so far has been Syria. In Yemen, Iranian-backed Houthi rebels are fighting against forces loyal to the government of President Abdrabbuh Mansour Hadi, which is supported by Saudi Arabian air strikes. The conflict has created a catastrophic humanitarian crisis in which, according to the UN, a child dies every ten minutes. In early November, a missile was fired by Yemen’s armed Houthi group toward Riyadh and intercepted en route by the Saudis. A second balistic missile fired by the Houthis later that month was also brought down. This was clearly a message from Iran; the Yemenis are not likely to possess such sophisticated military hardware. Iran’s president, Hassan Rouhani, claims to be working toward a rapprochement with Saudi Arabia, but the two nations continue to jostle for regional supremacy. Hariri’s sudden fall from power and the rising sectarian tension in Lebanon have created fear that the country will be the next battleground of the Saudi-Iranian proxy war. In the middle of this uncertainty are Syrian refugees.

The experience of refugees in Lebanon is an extended waiting game. The government has made clear that it wants to prevent their integration into Lebanese society in order to ensure that they won’t stay, as the Palestinians have. Lebanon barely tolerates the Palestinians; it certainly does not embrace them. The miserable refugee complex of Sabra and Shatila—a sprawling place of desperation and hopelessness—is a testament to that.

The Ouiza refugee settlement outside Sidon, where Syrian refugees are dumped, is next to a Palestinian refugee camp called Ain al-Hilweh—Arabic for “sweet water spring.” In August, clashes at the Palestinian camp between police and Sunni Islamists left two dead, and in April, seven people were killed. I spoke to three men from the Syrian city of Hama whose stories were familiar—their lack of work, adequate housing, and medical care, their trauma of escaping a burning country, but also their profound sense of indignity in exile. In Ouiza, they spin out their days in boredom and confusion. Ismail, at thirty, is the oldest of the group and tells me that when he does work as a laborer in the nearby town of Sidon, he can earn about 50,000 Lebanese pounds (approximately $30) in two days—only enough to cover the cost of a doctor’s visit for his kids, who often get sick. The last time he went to pick up a prescription, a group of Lebanese men taunted him with “Nique ta mère”—Fuck your mother—and threw stones at him.

Advertisement

When I visited in October, it was olive season. Many of the children were out picking olives or selling tissues on the streets. The teenage boys weren’t in school; they lumbered through their days, increasingly bored and agitated. “There’s a lot of neglect with these kids,” explains Kevin Charbel, an Irish aid worker from the Belgian aid organization Soutien Belge. “It’s not that their parents don’t love them, it’s just that they have no idea how to raise them in these circumstances.” Baha, another of the three men from Hama whom I spoke to, told me he was twenty when he got to Lebanon. His education was interrupted: he feels that his life has simply halted. It’s a miserable predicament, he says, to have the sense of waiting for something to happen. “I’ve spent six years here, doing nothing. When I was twenty, I thought I had a future. These six years, I’ve become twenty years older.” Some days, he says, he’d rather die in his country than be humiliated here every single day.

Many Lebanese fear that the settlements are, or will become, hotbeds of radicalism. Sheikh al-Rafei, the leader of the Salafist community in Lebanon, warned that refugees suffering from a sense of dislocation and social humiliation could easily be preyed upon by radical recruiters. This is the technique used by zealous preachers in the isolated banlieues of France, and it wouldn’t be hard to replicate in Lebanon. Syrian refugees live in open “settlements,” which are often simply abandoned buildings on the outskirts of towns, or even unheated garages. Anyone can just drive in.

There is special concern about children who have grown up in refugee settlements and do not remember the old life in Homs, Aleppo, or Hama. “Many of these kids don’t know what Syria is or where they come from,” says Jassen, a twenty-seven-year-old refugee from Raqqa whom I met in Tripoli. “They don’t know the flag, or the country.” During a visit to an outdoor “shift school,” I saw Syrian preschoolers being taught to draw a Syrian flag. Khalil el Helou, a retired Lebanese general, told me that he feared these children could be easily recruited. “Imagine a young Syrian, eight years old. If he lives like this for ten more years, imagine him at eighteen. If they are not contained in Lebanon,” he added, “they will be more dangerous on the streets of Manhattan.”

Patricia Khoder, a journalist with L’Orient Le Jour, a Beirut daily, has expressed other reasons for Lebanese antipathy to refugees. “Look—we had thirty years of Syrian occupation,” she said, referring to the Syrian troops that were sent to protect Christians during the civil war but overstayed their welcome by decades. At one point, President Hafez al-Assad even sent his son, Bashar, to oversee the Syrian forces in Lebanon. The Syrians did not leave until after Rafik Hariri’s assassination in 2005. Khoder likens the current refugee crisis to an imaginary scenario in postwar France. If 20 million German refugees had descended on Paris in the aftermath of the Nazi occupation, she tells me, “I don’t think the French would have accepted that. How can we?”

Last summer, a video went viral of a group of Lebanese men, since detained, who physically and verbally assaulted a Syrian refugee called Uklah from Deir-al-Zour in eastern Syria, demanding that he renounce his country and ISIS. The BBC reported a “voice note” that was widely shared on WhatsApp calling on Lebanese to “beat Syrians.” These events are not uncommon. They illustrate a recent rise in crimes and hate speech directed at refugees, who have become scapegoats for a variety of Lebanese grievances. A Lebanese businessman named Alan Bey compared them to Mexican-Americans: “They work hard and do the work the Lebanese don’t want to do, but they get blamed for everything.”

Much of the hatred has been stirred up by the conniving foreign minister, Gebran Bassil, who in October famously said, “Yes, we are racist Lebanese,” adding, “and at the same time, we are open to the world, and no one has the right to lecture us about being humanitarian.” This was a jab at European countries that have taken a fraction of the refugees that Lebanon has.

Bassil is forty-seven and the son-in-law of President Michel Aoun, a former Lebanese army general. He is the leader of the Free Patriotic Movement, also known as the Aounist Party, the largest Christian party and the second largest in Lebanon’s parliament. An engineer by training, he became foreign minister in 2014, and has his eye on the Lebanese election next May. His strategy is not sophisticated: “Bassil is trying to radicalize Lebanese people,” says Ziad el Sayegh, a senior adviser to the Ministry of State for Displaced Persons. “It’s simple. Raise fear in Lebanese society, polarize votes.” Many Lebanese find Bassil and his rhetoric odious. One political analyst refers to him as “Im-Bassile.” But like Nigel Farage, who played a large part in encouraging pro-Brexit sentiment, there are many who listen to him. “Bassil started very early on trying to gain political traction by creating a panic about the refugees,” says Nadim Shehadi, who is Lebanese, from the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University.

Advertisement

One night in Beirut I attended a gala in support of freedom of the press and whistleblowers. The annual event is hosted by a Maronite Christian journalist, Dr. May Chidiac, who lost a leg and an arm in a car bomb after criticizing the Syrian regime in 2005. The assassination attempt on Chidiac came after Rafik Hariri’s murder, along with a string of others. No one took responsibility, but Chidiac has openly blamed Hezbollah.

It was the Lebanese version of the Oscars—red carpets, women in long ball gowns, waiters in black tie serving iced Johnny Walker Red and champagne cocktails, and Beirut’s shiniest politicians, diplomats, businessmen, actors, and crooners. Models lounged on white leather sofas. A troupe of dancers did a routine from Grease and drove a pink Cadillac convertible onto the stage. It was a long way from the Ouiza settlement. A Lebanese socialite who asked me not to use her name told me, “We can’t handle the refugee situation, we can’t cope.” Her shrill tone echoed not only Bassil but also his father-in-law, President Aoun, who gave an identical quote to a group of foreign diplomats: “We can’t cope.”

Bassil’s xenophobia has been apparent for years; as energy minister, he blamed power cuts in Lebanon on refugees and foreigners. Now he demands that the Syrians go home—immediately. “Syrian citizens have only one route, which is the route that leads them to their homeland,” he said on a recent trip to the Bekaa Valley. Then billboards started going up in Beirut that said: “We will not become a minority in our own villages and cities. Let’s gather in a mass rally to demand the departure of the Syrians.”

Some refugees are already being forced home. Last summer in Arsal, a border town, a repatriation deal brokered by Hezbollah and the armed Syrian opposition forces initiated two separate deportations of thousands of refugees back to Syria. Some were combatants, but many were civilians—wives and children. The UN was not present to witness the exodus. Such deportations violate international law and set a dangerous precedent for dealing with a complicated crisis. They leave the Syrian men who return vulnerable to conscription into Assad’s army. Mireille Girard, the head of the UN Refugee Agency in Lebanon, said: “There is a fear in Lebanon that the longer refugees stay, the less they may want to go back.“ She added that although they want to go home, they will do so only when “they feel confident and safe. Return is about trust.”

There is real anxiety about Hezbollah’s domination in Lebanon, and about Iran’s not very subtle aim of expanding Shia power from Tehran to Beirut. The Saudis, meanwhile, are seeking to prop up their own Sunni fighters in Syria, stretching the proxy war over the border into Lebanon. And Syrian refugees are caught in the middle. The conflict is especially apparent in cities like Arsal and Tripoli, Lebanon’s second-largest city and a northern coastal Sunni stronghold with strong links to the towns of Hama and Homs in Syria.

In Tripoli, Islamic militants who oppose President Assad are fighting both Assad’s supporters (in the form of Alawite armed groups) and the Lebanese government. Armed conflict has swept across parts of Tripoli such as the Alawite Jabal Mohsen area and the Sunni Bab al-Tabbaneh district, with Sunni refugees finding themselves in the midst of the violence. Residents of both neighborhoods fight on opposite sides in Syria, and then come home and continue the conflict. “We are just waiting for an order from Saudi Arabia to open up the next battle,” a local commander told a German reporter in 2015. “We have to protect our Sunni community here.”

Attempts have been made to foster “cultural unity”—multifaith cafés, theatrical collaborations, academic studies. But at the Taqwa Mosque, which has been a recruiting ground for young Lebanese Sunnis to go fight in Syria, Sheikh Salem al-Rafei told me that the situation was “very critical. Worse than ever.” When Sheikh Rafei, who survived an assassination attempt allegedly by Hezbollah in 2013, gave a sermon to a crowd consisting largely of Syrian refugees, he encouraged them to no longer tolerate their marginalization. He cited their lack of status in Lebanese society, their lack of a future, the humiliations they face every day, and the deepening sectarian divisions in Lebanon. This was a week before Prime Minister Hariri resigned in Saudi Arabia. During the bloody battle for the border town of Al-Qusayr in 2013, when Hezbollah sent fighters to aid Assad’s army, Sheikh Rafei sent his own men. “It was a religious duty to fight in Syria,” he said. About thirty fighters from Tripoli alone died fighting in Al-Qusayr. As a devout Salafist, he is determined that Sunnis will not lose in the sectarian conflict.

At the heart of the issue is the absence of an official policy or long-term strategy for what to do with the refugees. When the Syrian civil war began in 2011, Lebanon and other “front-line” states (Turkey, Jordan) maintained an “open-door policy.” Nadim Shehadi, from the Fletcher School, recalled that in 2012 Prime Minister Najib Mikati and his advisers called donors and UN Agencies asking for help in dealing with 50,000 refugees. He was told that the agencies were already overstretched and was asked to “present a plan.” Mikati did not do so because refugees were crossing the border in very high numbers and it was impossible to predict how many more would come. “Mikati was right,” says Shehadi in retrospect. “Had he made a plan, mindful of 200,000 refugees, his plan would have collapsed once the number had grown to one million refugees. The entire system would have collapsed. Now there are 1.5 million.”

Khalil el Helou, a retired Lebanese general whose family came from Syria in 1970 and who now advises the government, has suggested one sort of official policy. He recommends that Lebanon contain and police refugee settlements, preferably with an international force, to prohibit jihadist recruiters from entering. He is not sure who would fund this policy, and acknowledges that the international community has already done a poor job of providing enough humanitarian aid in Syria. But we have to act soon, he says. “If we don’t, we are creating a new generation of terrorists who will strike at Beirut—or New York.”

The Syrian war will eventually end—painfully, and without the result the United States government wants to see: the end of the Assad regime. As for the refugees, no one seems to have any idea what to do with them. “Sometimes there simply is no solution,” Nadim Shehadi admits. “We’ll do the same thing we do with the Palestinian issue, that is, turn a blind eye. But the future is very alarming. If one percent of the refugees radicalize and decide to take up arms to fight, that is 25,000 radicalized people. Only one percent is in fact a lot.”

—January 10, 2018

This Issue

February 8, 2018

To Be, or Not to Be

Female Trouble

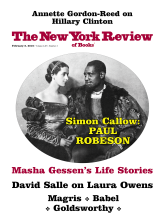

The Emperor Robeson